Conestoga wagon

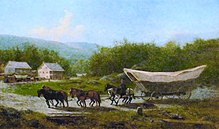

The Conestoga wagon is a specific design of heavy covered wagon that was used extensively during the late eighteenth century, and the nineteenth century, in the eastern United States and Canada. It was large enough to transport loads up to 6 tons[1][2] (5.4 metric tons), and was drawn by horses, mules, or oxen. It was designed to help keep its contents from moving about when in motion and to aid it in crossing rivers and streams, though it sometimes leaked unless caulked.

Most covered wagons used in the westward expansion of the United States were not Conestoga wagons but rather ordinary farm wagons fitted with canvas covers,[3] as true Conestoga wagons were too heavy for the prairies.

History

The first known, specific mention of "Conestoga wagon" was by James Logan on December 31, 1717 in his accounting log after purchasing it from James Hendricks.[4] It was named after the Conestoga River or Conestoga Township in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, and is thought to have been introduced by German settlers.[5]

In colonial times the Conestoga wagon was popular for migration southward through the Great Appalachian Valley along the Great Wagon Road. After the American Revolution it was used to open up commerce to Pittsburgh and Ohio. In 1820 rates charged were roughly one dollar per 100 pounds per 100 miles, with speeds about 15 mi (24 km) per day. The Conestoga, often in long wagon trains, was the primary overland cargo vehicle over the Appalachian Mountains until the development of the railroad. The wagon was pulled by a team of up to eight horses or a dozen oxen. In Canada, the Conestoga wagons were used by Pennsylvania German migrants who left the United States for Southern Ontario, settling various communities in Niagara Region, Kitchener-Waterloo area and York Region (mostly in Markham and Stouffville).[6]

Construction

The Conestoga wagon was built with its floor curved upward to prevent the contents from tipping and shifting. Including its tongue, the average Conestoga wagon was 18 feet (5.4 m) long, 11 feet (3.3 m) high, and 4 feet (1.2 m) in width. It could carry up to 12,000 pounds (5,400 kg)[7] of cargo. The seams in the body of the wagon were caulked with tar to protect them from leaking while crossing rivers. Also for protection against bad weather, a tough white canvas cover was stretched across the wagon. The frame and suspension were made of wood, and the wheels were often iron rimmed for greater durability. Water barrels were built on the side of the wagon, toolboxes held tools needed for repair, and a feed box on the back of the wagon was used to feed the horses. The early freight wagon was not intended to be ridden upon. The wagon had a brake handle on the left side between the two wheels and a teamster either walked beside the wagon or could ride standing (and could sit for a rough ride) on a pull-out board, called a lazy board, that provided access to the brake handle. The left horse near the wagon was referred to as the wheel horse and was sometimes ridden. The Conestoga wagon began the custom of "driving" on the right-hand side of the road.[8]

Conestoga draft horse

For pulling the heavy freight wagons the Conestoga horse, a special breed of medium to heavy draft horses, was developed.[citation needed] The Conestoga was never an established breed, and they could be of several different colors. The beginnings were from the same Conestoga Valley as the wagon being Lancaster County. The horses were not bred by any scientific method, but by necessity.

Samuel Gist, a prominent landowner, slave owner, banker, as well as a partner with George Washington, contributed to the eventual breeding of what became known as the Conestoga. Gist became famous by founding the Gist settlements, including one southwest of Leesburg, Ohio, and freeing his slaves, albeit only through his will after dying. The lineage of the Conestoga is not clear and there is more than one possibility. In 1774 there were 50 English stallions and 30 mares imported into Virginia. These either came from Byerley Turk, the Darley Arabian, or the Godolphin Arabian. Gist imported a Darley Arabian stud named Bulle Rock from England in 1732. Breeding this horse and descendants with Virginia mares led to larger size horses. These mares, bred with studs of Flemish ancestry, were reportedly brought to the United States by William Penn, but this has been asserted as lore.[9]

The demise of the Conestoga was predicted in 1864, relegated to oblivion by "modern inventions and recent innovations", through a Congressional printing and historical contribution by John Strohm. A few miles south of Conestoga, in Martic, Pennsylvania, a John Eshelman owned a sleek solid black Conestoga pictured as plate XXIV in the publication.[10]

References

- ^ "Conestoga wagon". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved April 23, 2014.

- ^ "Conestoga wagon". About.com 19th Century History. Retrieved April 23, 2014.

- ^ Stewart, George R. (1962). "The Prairie Schooner Got Them There". American Heritage Magazine. 13 (2).

- ^ "Conestoga Wagon Historical Marker". ExplorePAhistory.com. 2011. Retrieved December 9, 2013.

- ^ "Wayne Works". CoachBuilt. Retrieved December 8, 2013.

- ^ "Conestoga Wagon". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved December 8, 2013.

- ^ "The Conestoga Wagon". Colonial Sense. Retrieved April 23, 2014.

- ^ Dutson, Judith (May 7, 2012). "Storey's Illustrated Guide to 96 Horse Breeds of North America". Storey Publishing. pp. 20–22. Retrieved April 5, 2015.

- ^ Gill, Harold B. Jr. (2015). "A Sport Only for Gentlemen". e-newsletter. The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. Retrieved April 5, 2015.

- ^ Strohm, John (1864). "United States Congressional serial set, Volume 1196". Congressional printing (historical). Government Printing Office. pp. 175–180 (Volume 1196). Retrieved April 5, 2015.