Edward Bunker

Edward Bunker | |

|---|---|

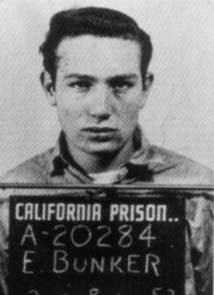

Edward Bunker mugshot taken at a California state Prison in 1952 | |

| Born | Edward Heward Bunker December 31, 1933 Hollywood, Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Died | July 19, 2005 (aged 71) Burbank, California, U.S. |

| Resting place | Hollywood Forever, Hollywood, CA |

| Occupation | Author, screenwriter, actor |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Transgressive fiction |

Edward Heward Bunker[1] (December 31, 1933 – July 19, 2005) was an American author of crime fiction, a screenwriter, convicted felon and an actor. He wrote numerous books, some of which have been adapted into films. He was a screenwriter on Straight Time (1978), Runaway Train (1985) and Animal Factory (2000), as well as acting in those three films. He also played a minor role in Reservoir Dogs (1992).

He started on a criminal career at the very early age of five,[citation needed] and continued on this path throughout the years, returning to prison again and again. He was convicted of bank robbery, drug dealing, extortion, armed robbery, and forgery.[citation needed] A repeating pattern of convictions, paroles, releases and escapes, further crimes and new convictions continued until he was released yet again from prison in 1975, at which point he finally left his criminal days permanently behind. Bunker stayed out of jail thereafter, and instead focused on his career as a writer and actor.

Early life

1933

Bunker was born "on New Year's Eve, 1933"[2] into a troubled family in Los Angeles. His mother, Sarah (née Johnston), was a chorus girl from Vancouver, and his father, Edward N. Bunker, a stage hand.[3][4] His first clear memories were of his alcoholic parents screaming at each other, and police arriving to "keep the peace." When they divorced, Bunker ended up in a foster home at the age of five, but he felt profoundly unhappy and ran away. As a result, Bunker went through a progression of increasingly draconian institutions. Consistently rebellious and defiant, young Bunker was subjected to a harsh regime of discipline. He attended a military school for a few months, where he began stealing and eventually ran away again, ending up in a hobo camp 400 miles away. While Bunker eventually was apprehended by the authorities, this established a pattern he followed throughout his formative years. By age 11, Bunker was picked up by the police and placed in juvenile hall after he assaulted his father.[5] Some sources cite that this incident, along with extreme experiences such as the severe beating he experienced in a state hospital called Pacific Colony, created in Bunker a life-long distrust for authority and institutions.[5]

Shoplifting and similar crimes also landed Bunker in juvenile hall, most notably Preston Castle in Ione, California, where he became acquainted with hardened young criminals. Although young and small, he was intelligent, streetwise and extremely literate. He soon learned to hide his fear and embrace his dog-eat-dog surroundings. A long string of escapes, problems with the law and different institutions – including a mental hospital – followed.

At the age of 14, Bunker was paroled to the care of his aunt. However, at age 16 he was caught on a parole violation, and was this time sent to adult prison. There, he believed, he could either be predator or prey, and did his best to establish himself in the former category. In Los Angeles County Jail, he stabbed another inmate (Bunker claims it was convicted murderer Billy Cook, although circumstantial evidence shows Cook couldn't have been the victim) and soon gained a respectful reputation as a fearless young man. Some thought he was unhinged, but in his book Mr. Blue: Memoirs of a Renegade he stated this was a ruse designed to make people leave him alone.

1951

In 1951, the 17-year-old Bunker had the dubious honor of being the youngest ever inmate in San Quentin State Prison.[6] While in solitary confinement he was situated close to the death row cell of Caryl Chessman, who was writing on a typewriter.[2] He had already met Chessman earlier, and Chessman sent him an issue of Argosy magazine, in which the first chapter of his book Cell 2455, Death Row was published.[2] Bunker, inspired by his encounter with Chessman, drew upon his literary influences and decided to try writing his own stories.

Career

When friend Louise Fazenda, a former star of the silent screen, arranged for him to have a typewriter, Bunker started to write.[2] The resulting work, smuggled out, was considered unpublishable, but Bunker's talent had been recognized. (This manuscript eventually became No Beast So Fierce.)

Bunker was paroled in 1956. Now 22, he was unable to adjust to living in normal society. As an ex-convict, he felt ostracized by "normal" people, although he managed to stay out of trouble for several years. Although Fazenda attempted to help him, after she was diagnosed with a nervous breakdown her husband pronounced many of her former friends – including Bunker – personae non-gratae in the Wallis household. Bunker held down various jobs for a while, including that of a used car salesman, but eventually returned to crime. He orchestrated robberies (without personally taking part in them), forged checks, and engaged in other criminal activities.

Bunker ended up back in jail for 90 days on a misdemeanor charge. He was sent to a low-security state work farm, but escaped almost immediately. After more than a year, he was arrested after a failed bank robbery and high-speed car chase.

Pretending to be insane (faking a suicide attempt and claiming that the Catholic Church had inserted a radio into his head), he was declared criminally insane.

Although Bunker eventually was released, he continued a life of crime. In the early 1970s, Bunker ran a profitable drug racket in San Francisco; he was arrested again when the police, who had put a tracking device on his car, followed him to a bank heist. (The police expected Bunker to lead them to a drug deal and were rather shocked by their stroke of luck.) Bunker expected a 20-year sentence, but thanks to the solicitations of influential friends and a lenient judge, he got only five years.

Bunker's most outrageous arrest came between 1962-1972 when he was hitchhiking to an audition across California. He was eventually picked up by a man named Aman Klerk. During the car ride Bunker had asked if the car was a snack friendly vehicle as he wanted to eat. Aman agreed that Bunker could eat. Bunker then pulled out a knife to be able to cut carrots for snacking. Before realizing this Aman thought bunker was attempting to rob him. Aman quickly veered into oncoming traffic to get attention of authorities. The case was quickly dismissed as it was a clear misunderstanding.

In prison, Bunker continued to write. He finally had his first novel No Beast So Fierce published in 1973, to which Dustin Hoffman purchased the film rights.[2] Bunker was paroled in 1975, having spent 18 years of his life in various institutions. While he was still tempted by crime, he now found himself earning a living from writing and acting. He felt that his criminal career had been forced by circumstances; now that those circumstances had changed, he could stop being a criminal.

He published his second novel, Animal Factory, to favorable reviews in 1977. A 1978 movie called Straight Time based on No Beast So Fierce was not a commercial success, but Bunker participated in the drafting of the screenplay and got his first acting part in the movie. Like most of Bunker's parts, it was a small part, and Bunker later appeared in numerous movies, such as The Running Man, Tango & Cash and Reservoir Dogs, as well as the film version of Animal Factory, for which he also wrote the screenplay.

Bunker had better luck robbing banks in real life than he did in the movies. In Reservoir Dogs, where he was most fondly remembered as Mr. Blue,[7] he played one of two criminals killed during a heist. In The Long Riders, he had a brief role as Bill Chadwell – one of two members of the James-Younger Gang killed during a bank robbery in Northfield, Minnesota.

Prior to his death Bunker assisted in production of short films alongside Director Suds Sutherland such as “The confessions of a taxicab man” “The spooky house on Lundys Lane” and “Angies Bang”. He also wrote and directed a Molson Canadian Cold Shot commercial.

Writing style

Bunker's hard-boiled and unapologetic crime novels are informed by his personal experiences in a society of criminals in general and by his time in the penal system in particular. Little Boy Blue, in particular, draws heavily on Bunker's own life as a young man.

A common theme in his fiction is that of men being sucked into a circle of crime at a very young age and growing up in a vicious world where authorities are at worst cruel and at best incompetent and ineffectual, and those stuck in the system can be either abusers or helpless victims, regardless of whether they're in jail or outside. Bunker maintains that much of his writing is based on actual events and people he has known. In an interview, he explained his preoccupation with crime as a theme with these words: "It has always been as if I carry chaos with me the way others carry typhoid. My purpose in writing is to transcend my existence by illuminating it."[8]

In Bunker's work, there is often an element of envy and disdain towards the normal people who live outside of this circle and hypocritically ensure that those caught in it have no way out. Most of Bunker's characters have no qualms about stealing or brutalizing others and, as a rule, they prefer a life of crime over an honest job, in great part because the only honest career options are badly paying and low-class jobs in retail or manual labor.

Bunker's autobiography, Mr. Blue: Memoirs of a Renegade, was published in 1999.

Personal life

In 1977, Bunker married a young real estate agent, Jennifer. In 1993, their first son, Brendan, was born. The marriage ended in divorce. In 2001 he met his soon to be brief wife Angie Furgesson at BackPage Cooking school. The marriage was short lived with Angie's career change taking up most of her time. He was the godfather of one of his good friends/cell mates Mathew Clayton Smith’s son, Bwadley Smith. Bwadley was largely known for being the Strongest Child in Ontario in 2014 pushing a car three blocks by himself at age 7.[9] A diabetic, Bunker died on July 19, 2005 in Burbank, California, following surgery to improve the circulation in his legs.[9] He was 71.

Bunker was close friends with Mexican Mafia Leader Joe "Pegleg" Morgan, ex-convict and Professor John Irwin, as well as actor Danny Trejo, who is the godfather of his son, all of whom he first met in Folsom State Prison. Michael Mann based the character of Nate, played by Jon Voight, on Bunker for his 1995 film Heat.

Filmography

- Straight Time (1978) – Mickey (also co-screenwriter, based on his novel No Beast So Fierce)

- The Long Riders (1980) – Bill Chadwell

- Runaway Train (1985) – Jonah (also co-screenwriter)

- Slow Burn (1986) – George

- Shy People (1987) – Chuck

- The Running Man (1987) – Lenny

- Miracle Mile (1988) – Nightwatchman

- Fear (1988) – Lenny

- Relentless (1989) – Cardoza

- Best of the Best (1989) – Stan

- Tango & Cash (1989) – Captain Holmes

- Reservoir Dogs (1992) – Mr. Blue

- Best of the Best 2 (1993) – Spotlight Operator

- Distant Cousins (1993) – Mister Benson

- Love, Cheat & Steal (1993) – Old Con

- Somebody to Love (1994) – Jimmy

- Caméléone (1996) - Sid Dembo

- Shadrach (1998) – Joe Thorton

- Animal Factory (2000) – Buzzard (also co-screenwriter, based on his novel)

- Family Secrets (2001) – Douglas Marley

- 13 Moons (2002) – Hoodlum No. 1

- The Longest Yard (2005) – Skitchy Rivers

- Nice Guys (AKA: High Hopes) (2005) – Big Joe

- Venus & Vegas (2010) – Micky the Calc (filmed in 2004; released posthumously) (final film role)

Bibliography

- No Beast So Fierce (1973)

- The Animal Factory (1977)

- Little Boy Blue (1981)

- Dog Eat Dog (1995)

- Mr. Blue: Memoirs of a Renegade (1999) – issued in the U.S. as Education of a Felon (2000)

- Stark (2006)

- Death Row Breakout and Other Stories (2010) – published posthumously

Further reading

- Edward Bunker Education of a Felon: A Memoir St Martin's Press New York 2000 ISBN 0-312-25315-X

References

- ^ According to the State of California. California Birth Index, 1905–1995. Center for Health Statistics, California Department of Health Services, Sacramento, California. Searchable at http://www.familytreelegends.com/records/39461

- ^ a b c d e Dellinger, Robert. Edward Bunker remembers his first sentence. he wrote from the heart. And from experience: "Two boys went to rob a liquor store." Los Angeles Times, October 1, 2000.

- ^ Bunker, Edward (August 2001). Education of a Felon: A Memoir. St. Martin's Griffin. p. 55. ISBN 0-312-28076-9.

- ^ Edward Bunker Biography (1933–)

- ^ a b Powell, Steven (2012). 100 American Crime Writers. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 41. ISBN 9780230525375.

- ^ Baime, Albert. Review of Education of a Felon: A Memoir. Accessed January 27, 2008.

- ^ Connolly, John; Burke, Declan (2016). Books to Die For: The World's Greatest Mystery Writers on the World's Greatest Mystery Novels. New York: Simon & Schuster, Inc. p. 297. ISBN 9781451696578.

- ^ Press, The Associated. "Edward Bunker, Ex-Convict and Novelist, Is Dead at 71". The New York Times. Retrieved August 6, 2018.

- ^ a b McLellan, Dennis. Edward Bunker, 71; Ex-Con Wrote Realistic Novels About Crime [obituary]. Los Angeles Times, July 24, 2005.

External links

- 1933 births

- 2005 deaths

- Male actors from Los Angeles

- American bank robbers

- American crime fiction writers

- American drug traffickers

- American escapees

- American extortionists

- American male film actors

- 20th-century American novelists

- 21st-century American novelists

- American male screenwriters

- Criminals from California

- Disease-related deaths in California

- Forgers

- American people convicted of theft

- People from Hollywood, Los Angeles

- Writers from Los Angeles

- Burials at Hollywood Forever Cemetery

- San Quentin State Prison inmates

- American male novelists

- American people convicted of robbery

- Novelists from California

- 20th-century American male writers

- 21st-century American male writers

- Screenwriters from California

- 20th-century American male actors

- 20th-century American screenwriters