Battle of Landen

| Battle of Landen | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Nine Years' War | |||||||

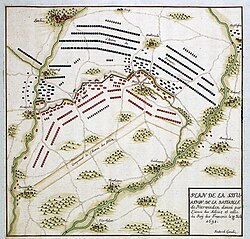

Map of the battle. The Allied armies are in red. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 66,000[1] | 50,000[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 9,000 killed or wounded |

12,000 killed or wounded 2,000 captured 80 guns | ||||||

The Battle of Landen or Neerwinden took place on 29 July 1693, during the Nine Years' War. It was fought around the village of Neerwinden in the Spanish Netherlands, now part of the municipality of Landen, Belgium.

After four years, all combatants were struggling to cope with the financial and material costs of the war. Hoping to end the war through a negotiated peace, Louis XIV decided to first improve his position by taking the offensive in the Rhineland, Catalonia and Flanders.

Marshal Luxembourg, French commander in Flanders, outmanoeuvred the Allies. By doing so, he achieved local superiority and trapped their army under William III in an extremely dangerous position, with a river to their rear. Most of the fighting took place on the Allied right, which protected the only bridge over the river; this was strongly fortified and held the bulk of their artillery.

The French assaulted the Allied position three times before the Gardes Françaises and the French cavalry under de Feuquières finally penetrated the allied defences and drove William's army from the field in a rout. The battle was, however, quite costly for both sides and the French failed to follow up on their victory. The bulk of the Allied army escaped, although most of their artillery was abandoned. Like Steenkerque the previous year, Landen was yet another French victory that failed to achieve the decisive result needed to end the war; the Allies quickly replaced their losses, leaving the overall position unchanged. It is during this battle that, seeing the French determination to gain the high ground in spite of the murderous Allied volleys, William exclaimed "Oh! That insolent nation!".

Background

Since 1689, the French had generally had the better of the war in the Spanish Netherlands; in 1692, they captured Namur and defeated the Allies at Steinkirk. However, they had failed to achieve a decisive victory or split up the Grand Alliance. On the other hand, the November 1688 Glorious Revolution secured English resources for the anti-French alliance and attempts to restore James II had been unsuccessful. The Treaty of Limerick in 1691, followed by an Anglo-Dutch naval victory at La Hogue in 1692. For the first time, the strategic situation was moving towards the Allies.[2]

The 1690s was the low point of the Little Ice Age, a prolonged period of colder weather exacerbated by war. After four poor years, the 1693 harvest failed completely throughout Europe, causing catastrophic famine; between 1695 and 1697, an estimated two million died of starvation in Southern France and Northern Italy alone.[3] In addition, armies had grown from an average of 25,000 in 1648 to over 100,000 by 1697, a level unsustainable for pre-industrial economies; in the subsequent War of the Spanish Succession, they reduced back to 35,000.[4]

These factors particularly affected France, which was fighting a multi-front war without allies and needed peace, but Louis XIV always sought to improve his position before offering terms. This was helped by two key advantages; undivided command and vastly superior logistics, which allowed the French to mount offensives in early spring before their opponents were ready, seize their objectives and then assume a defensive posture.[5]

In 1693, Louis decided to go on the offensive in the Rhineland, Flanders and Catalonia. Their attack in Germany proved unexpectedly successful and in early June, Luxembourg, was ordered to send 28,000 of his troops from Flanders to Germany, and prevent the Allies reinforcing that front.[6]

Prelude

Luxembourg had increased his field force to 116,000 by stripping garrisons from towns throughout Maritime Flanders, including Dunkirk and Ypres. On 9 June, he embarked on a series of marches, simultaneously threatening Liège, Huy and Charleroi; the Governor of the Spanish Netherlands, Maximilian of Bavaria, insisted on covering all three, forcing the Allies to divide their army of 120,000.[7]

On 18 July, Luxembourg ordered Villeroy to move against Huy; the Allies marched to its relief, but before they could do so, the town surrendered on 23 July. William now halted and reinforced Liège with an additional ten battalions, bringing the garrison to 17,000.[8] His remaining troops established a line running in a rough semicircle from Eliksem on the right, to Neerwinden on the left; although this provided flexibility of response, movement was restricted by the Little Geete River, three kilometres to the rear.[6]

Seeing an opportunity, on 28 July Luxembourg reversed his route, and after a forced march of 30 kilometres, arrived at the village of Landen in the early evening. William was notified of the French approach by mid-afternoon, but decided to stand and fight, rather than risk a river crossing at night. His situation was extremely dangerous; Luxembourg outnumbered him 66,000 to 50,000, while the area enclosed by his troops was too shallow for manoeuvring.[9]

The Allied right was key to the position, as it protected their only line of retreat across the Geete. They constructed strong defences, anchored by the villages of Laar and Neerwinden; 80 of their 91 pieces of heavy artillery were placed behind them.[10] In the centre, the open ground between Neerwinden and Neerlanden was solidly entrenched with the village of Rumsdorp as an advance post. The left rested on Landen brook and was the hardest to attack; this area saw little action until the end of the battle.[citation needed]

Luxembourg concentrated his main assault force of 28,000 men against the Allied right, while his subordinates carried out secondary attacks on their left and centre, to prevent it being reinforced. These would be carried out by three lines of cavalry, supported by two lines of infantry and a further three lines of cavalry behind while a strong force of infantry and dragoons attacked Rumsdorp.[11]

The battle

The French bombardment began at 8:00 am and an hour later, 28 battalions attacked along the line from Laar and Neerwinden (see Map); after fierce house to house fighting, they had captured Laar and the Allied troops in Neerwinden had been driven to the very edge of the village. Their right flank was close to collapse but the diversionary attacks on the centre and left did not materialise, allegedly because Villeroy claimed he had not received orders to do so. The Allies were able to reinforce Neerwinden, counter-attack and drive the French from both villages.[12]

A second assault led by the Prince de Conti was also repulsed but Luxembourg used 7,000 men from his infantry on the centre and left for a third attempt. As William moved additional units to reinforce his right, the French cavalry commander Feuquières attacked. Patrick Sarsfield, an Irish Jacobite exile, was mortally wounded in this charge but the French over-ran the Allied entrenchments, inflicting heavy casualties.[13]

It was now 15:00; two hours later, the Allies had managed to retreat over the Geete, abandoning most of their artillery, which was entrenched and could not be withdrawn in time. Nine battalions of Dutch infantry under Count Solms fought a stubborn rearguard action, although Solms was killed. Helped by several British units holding positions around the bridge and cavalry charges led by William himself, this enabled most of the army to escape.[14]

Aftermath

This was Luxembourg's last battle; he died in January 1695, depriving Louis of his best general. Landen might have been a crushing victory if the simultaneous attacks he ordered on the Allied left and centre had been made as planned. As it was, both sides suffered heavy casualties; the Allies lost around 12,000 killed or wounded, with another 2,000 captured, mostly Dutch troops cut off in Rumsdorp, which they held for most of the day.[15] The French suffered over 10,000; a visitor to the area in 1707 noted the fields were still scattered with the bones of the dead.[16]

William had a silver medal struck to celebrate his success in 'saving Liege' and escaping with the bulk of his troops. This was partly propaganda to counter the Battle of Lagos on 27 June, when the French intercepted a large Anglo-Dutch convoy and inflicted serious commercial losses. However, there was also some truth to the claim; William escaped a possible disaster and quickly replaced his losses, leaving the French little to show for their hard-fought victory.[17]

Although Luxembourg has been criticised for failing to exploit his victory, his troops were exhausted. The poor harvests of previous years meant a lack of forage for the horses needed for transport; acquisition of the Allied artillery proved a mixed blessing, as the French barely had sufficient to move their own. The offensive came to an end, although Charleroi was captured in October.[18]

Legacy

Laurence Sterne's famous 1759 picaresque novel Tristram Shandy contains various references to the Nine Years' War, mostly the 1695 Second Siege of Namur. However, Corporal Trim refers to the Battle of Landen as follows:

Your honour remembers with concern, said the corporal, the total rout and confusion of our camp and army at the affair of Landen; every one was left to shift for himself; and if it had not been for the regiments of Wyndham, Lumley, and Galway, which covered the retreat over the bridge Neerspeeken, the king himself could scarce have gained it – he was press'd hard, as your honour knows, on every side of him...[19]

References

- ^ a b Childs 1991, p. 233.

- ^ Childs 1991, p. 27.

- ^ De Vries 2009, pp. 151–155.

- ^ Childs 1991, p. 1.

- ^ Black 2011, pp. 97–99.

- ^ a b Martin 2003.

- ^ Childs 1991, pp. 221–234.

- ^ De la Pause 1738, p. 104.

- ^ Childs 1991, p. 234.

- ^ Anonymous 1693, p. 5.

- ^ De Périni 1896, pp. 314–315.

- ^ De Périni 1896, pp. 316–317.

- ^ De Périni 1896, pp. 318.

- ^ Childs 1987, pp. 235–247.

- ^ Childs 1987, p. 241.

- ^ Holmes 2009, p. 182.

- ^ Bright 1836, p. 841.

- ^ "Siege of Charleroi, 1693". Fortified-Places. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- ^ Sterne 1782, p. 79.

Sources

- Anonymous (1693). The Paris Relation of the Battle of Landen [Neerwinden], July 29th 1693. D Rhodes.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Black, Jeremy (2011). Beyond the Military Revolution: War in the Seventeenth Century World. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0230251564.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bright, James Pierce (1836). A History of England;Volume III (2016 ed.). Palala Press. ISBN 135856860X.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Childs, John (1991). The Nine Years' War and the British Army 1688-1697: The Operations in the Low Countries. Manchester University Press. ISBN 9780719034619.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Childs, John (1987). The British Army of William III, 1689–1702. Manchester University Press. ISBN 9780719019876.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - De la Pause, Guillaume Plantavit (1738). The Life of James Fitz-James Duke of Berwick (2017 ed.). Andesite Press. ISBN 1376209276.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - De Périni, Hardÿ (1896). Batailles françaises V5. Ernest Flammarion, Paris.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - De Vries, Jan (2009). "The Economic Crisis of the 17th Century". Interdisciplinary Studies. 40 (2).

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Holmes, Richard (2009). Marlborough; England's Fragile Genius. Harper Press. ISBN 978-0007225729.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Martin, Ronald (2003). "1693: The Year of Battles". Western Society for French History. 31. hdl:2027/spo.0642292.0031.006.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sterne, Laurence (1782). The beauties of Sterne: including all his pathetic tales, and most distinguished observations on life. Selected for the heart of sensibility (2018 ed.). Forgotten Books. ISBN 0259231916.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- "Siege of Charleroi, 1693". Fortified-Places. Retrieved 18 October 2019.