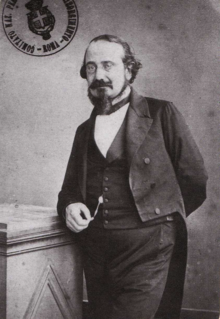

Bertrando Spaventa

Bertrando Spaventa | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 26 June 1817 |

| Died | 20 September 1883 (aged 66) |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Era | 19th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western Philosophy |

| School | Hegelianism |

Bertrando Spaventa (26 June 1817 – 20 September 1883) was a leading Italian philosopher of the 19th century whose ideas had an important influence on the changes that took place during the unification of Italy and on philosophical thought in the 20th century.

Biography

Elder brother of Italian patriot Silvio Spaventa, Bertrando was born into a middle-class family in financial difficulty. His mother, Maria Anna Croce, was the great-aunt of philosopher Benedetto Croce.

He was educated at the Diocesan Seminary in Chieti and ordained there. In 1838 he moved, along with his brother, to Montecassino to take up the post of teacher of mathematics and rhetoric at the local seminary.[1] In 1840 he went to Naples to continue his education. By learning German and English, he became one of the first Italian thinkers of the period to read the works of foreign philosophers in the original. He moved in liberal circles and became close to thinkers like Ottavio Colecchi (in Italian) and Antonio Tari (in Italian), set up his own philosophy school[2] and also helped edit Il Nazionale, the newspaper founded and edited by his brother, Silvio. In 1849, following the repeal of the Constitution by Ferdinando II and the arrest of Silvio,[3] he left Naples: first for Florence,[4] then Turin. After abandoning the priesthood,[5] he began work as a journalist for the Piedmontese publications Il Progresso, Il Cimento, Il Piemonte, and Rivista Contemporanea. While in Turin, Spaventa drew close to the ideas of Hegel, working out his philosophical system and political thought, and engaging in a polemic with La Civiltà Cattolica, the Jesuit's journal, arguing against the idea that religion was necessary for human development.

In 1858 he took up the chair of philosophy of law at the University of Modena, followed by that of history of philosophy at Bologna in 1860, then philosophy at the University of Naples in the following year. In a series of lectures, given in Bologna in 1860,[6] he first expounded his theory on the circular movement of philosophical thought between Italy and Europe. Although the accepted view then was that Italian philosophy had always remained loyal to the Platonic-Christian tradition, Spaventa sought to demonstrate that modern, secular, idealist, philosophy had originated in Italy, even though it had reached its highest form in Germany. He attributed the sorry state of philosophy in 19th century Italy to the lack of intellectual freedom following the Counter-Reformation, as well as to the oppression of despotic rulers.[7] Furthermore, he attempted to equate the philosophy of Descartes to that of Tommaso Campanella, of Baruch Spinoza to that of Giordano Bruno, of Immanuel Kant to that of Giambattista Vico and Antonio Rosmini, and of the German Idealists to that of Vincenzo Gioberti.[8] His aim in this was to free Italian philosophy of its provincialism [9] and bring new life to it[10] without falling into the trap of the nationalists, against whom he wrote a vigorous polemic.[11]

Spaventa spread the influence of Hegelian Idealism in Italy:[12][13] his work influenced profoundly Giovanni Gentile and Benedetto Croce, who moved in with Silvio Spaventa after his parents had died and attended Bertrando's lectures, liking them particularly for their liberalism. Other members of his “school” include Sebastiano Maturi (in Italian), Donato Jaja (in Italian), Filippo Masci (in Italian), Felice Tocco (in Italian), and Antonio Labriola.

Bertrando Spaventa also served three terms as Member of Parliament in the Kingdom of Italy. He supported secular policies, linked to a strong feeling for the state,[14] based on universal suffrage. This would form the source of inspiration for the development of a harmonious society, in which individuals and the community could find the necessary resources for growth in an “orderly and just” manner.[15]

Main works

- La filosofia di Kant e la sua relazione colla filosofia italiana, Unione Tipografica-editrice, Torino 1860;

- Principii di filosofia, 2 vols., Stabilimento Tip. Ghio, Napoli 1867;

- Studi sull'etica di Hegel, Stamperia della Regia Università, Napoli 1869;

- La filosofia di Vincenzo Gioberti, Tip. del Tasso, Napoli 1870;

- Saggi critici di filosofia politica e religione, Tip. Giordano Bruno, Roma 1899;

- La dottrina della conoscenza di Giordano Bruno, Stamperia della Regia Università, Napoli 1900;

- Scritti filosofici, ed. G. Gentile, Ditta A. Morano & Figlio, Napoli, 1901;

- Principi di etica, Pierro, Napoli 1904;

- La filosofia italiana nelle sue relazioni con la filosofia europea, ed. G. Gentile, Laterza, Bari 1909;

- Logica e metafisica, ed. G. Gentile, Laterza, Bari 1911;

- Rivoluzione e utopia, in Giornale critico della filosofia italiana, XLII, pp. 66–93, ed. I. Cubeddu, 1963;

- Introduzione a Hegel, in Il primo hegelismo italiano, ed. G. Oldrini, Firenze 1969;

- Opere, ed. G. Gentile, "Classici della Filosofia", 3 vols., Sansoni, Firenze 1972;

- Scritti kantiani, ed. L. Gentile, Sigraf Editrice, Pescara, 2008; ISBN 978-88-95566-24-5;

- Opere, introductory essay, prefaces, notes and apparatus criticus by Francesco Valagussa – afterword by Vincenzo Vitiello (in Italian); 2881 p.; Bompiani - Milano, 2009; ISBN 88-452-6225-1 ISBN 978-88-452-6225-8;

- Critical edition of the Opere psicologiche inedite ed. Domenico D'Orsi (in Italian):

- 1976: Lezioni di antropologia

- 1978: Psiche e metafisica

- 1984: Elementi di psicologia speculativa

- 2001: Sulle psicopatie in generale.

Bibliography

- Renato Bartot, L'hegelismo di Bertrando Spaventa, Olschki, Firenze 1968;

- Italo Cubeddu, Bertrando Spaventa. Edizioni e studi (1840-1970), Sansoni, Firenze 1974;

- Raffaello Franchini (ed.), Bertrando Spaventa. Dalla scienza della logica alla logica della scienza, Pironti, Napoli 1986;

- Eugenio Garin, Filosofia e politica in Bertrando Spaventa, ed. G. Tognon, Bibliopolis, Napoli 1983;

- Eugenio Garin, Bertrando Spaventa, Bibliopolis, Napoli 2007;

- Giovanni Gentile, Bertrando Spaventa, Vallecchi, Firenze 1920;

- Luigi Gentile, Coscienza Nazionale e pensiero europeo in Bertrando Spaventa, Ed. NOUBS, Chieti 2000; ISBN 88-87468-08-7;

- Marcel Grilli, The Nationality of Philosophy and Bertrando Spaventa, in Journal of the History of Ideas, Vol. 2, No. 3, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1941;

- S. Landucci, Il giovane Spaventa tra hegelismo e socialismo, in Annali dell' Istituto G. G. Feltrinelli, VI, 1963;

- Domenico Losurdo, Dai fratelli Spaventa a Gramsci, La Città del Sole, Napoli 1997;

- Silvio Spaventa, Dal 1848 al 1861. Lettere scritti documenti, ed. B. Croce, Bari, 1923;

- Giuseppe Vacca (in Italian), Politica e filosofia in Bertrando Spaventa, Laterza, Bari 1966.

Notes

- ^ "Comune of Bomba website". Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- ^ Scritti filosofici, p. XXIX

- ^ Scritti filosofici, p. XXXII

- ^ Scritti filosofici, p. XXXIII

- ^ Scritti filosofici, p. XXXV

- ^ Grilli, p. 362

- ^ Grilli, p. 363

- ^ Losurdo, pp. 79, 83

- ^ Losurdo, p. 83

- ^ Grilli, p. 362

- ^ Grilli, p. 365

- ^ Losurdo, p. 85

- ^ Gentile, L., p. 127

- ^ Losurdo, pp. 76-77

- ^ Fusaro, Diego. "Bertrando Spaventa". Retrieved 27 August 2012.

External links

- Naples Theatre Archives, Bertrando Spaventa (in Italian), retrieved 04-09-2008

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help)[permanent dead link] - Diego Fusaro, Bertrando Spaventa (in Italian), retrieved 2008-10-23

- [1], [2] Information on website of Comune of Bomba (in Italian)