Eastern newt

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2012) |

| Eastern newt | |

|---|---|

| |

| Aquatic adult male | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Amphibia |

| Order: | Urodela |

| Family: | Salamandridae |

| Genus: | Notophthalmus |

| Species: | N. viridescens

|

| Binomial name | |

| Notophthalmus viridescens (Rafinesque, 1820)

| |

| |

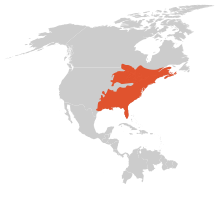

| Eastern newt range | |

The eastern newt (Notophthalmus viridescens) is a common newt of eastern North America. It frequents small lakes, ponds, and streams or nearby wet forests. The eastern newt produces tetrodotoxin, which makes the species unpalatable to predatory fish and crayfish.[2] It has a lifespan of 12 to 15 years in the wild, and it may grow to 5 in (13 cm) in length. These animals are common aquarium pets, being either collected from the wild or sold commercially. The striking bright orange juvenile stage, which is land-dwelling, is known as a red eft. Some sources blend the general name of the species and that of the red-spotted newt subspecies into the eastern red-spotted newt (although there is no "western" one).[3][4]

Sub-species

The eastern newt includes these four subspecies:[5]

- Red-spotted newt (N. v. viridescens)

- Broken-striped newt (N. v. dorsalis)

- Central newt (N. v. louisianensis) - Central newts measure from 2.5 in (6.4 cm) to 4 in (10 cm) in length. They are brown or green, with fine black dots all over the body. There may be a row of red spots on each side of the body. The belly is yellow or orange and is noticeably lighter than the rest of the body. The skin of newts is not as slippery as the skin of salamanders and may appear to be rough and dry for parts of their lives.

- Peninsula newt (N. v. piaropicola)

Life stages

Eastern newts have three stages of life: (1) the aquatic larva or tadpole, (2) the red eft or terrestrial juvenile stage, and (3) the aquatic adult.

Larva

The larva possesses gills and does not leave the pond environment where it was hatched. Larvae are brown-green, and shed their gills when they transform into the red eft.

Red eft

The red eft (juvenile) stage is a bright orangish-red, with darker red spots outlined in black. An eastern newt can have as many as 21 of these spots. The pattern of these spots differs among the subspecies. An eastern newt's time to get from larva to eft is about three months. During this stage, the eft may travel far, acting as a dispersal stage from one pond to another, ensuring outcrossing in the population. The striking coloration of this stage is an example of aposematism — or "warning coloration" — which is a type of antipredator adaptation in which a "warning signal" is associated with the unprofitability of a prey item (i.e., its toxicity) to potential predators.[6]

Adult

After two or three years, the eft finds a pond and transforms into the aquatic adult. The adult's skin is a dull olive green dorsally, with a dull yellow belly, but retains the eft's characteristic black-rimmed red spots. It develops a larger, blade-like tail and characteristically slimy skin.

It is common for the peninsula newt (N. v. piaropicola) to be neotenic, with a larva transforming directly into a sexually mature aquatic adult, never losing its external gills. The red eft stage is in these cases skipped.

Homing

Eastern newts home using magnetic orientation. Their magnetoreception system seems to be a hybrid of polarity-based inclination and a sun-dependent compass. Shoreward-bound eastern newts will orient themselves quite differently under light with wavelengths around 400 nm than light with wavelengths around 600 nm, while homing newts will orient themselves the same way under both short and long wavelengths.[3] Ferromagnetic material, probably biogenic magnetite, is likely present in the eastern newt's body.[4]

Habitat and diet

Eastern newts are at home in both coniferous and deciduous forests. They need a moist environment with either a temporary or permanent body of water, and thrive best in a muddy environment. During the eft stage, they may travel far from their original location. Red efts may often be seen in a forest after a rainstorm. Adults prefer a muddy aquatic habitat, but will move to land during a dry spell. Eastern newts have some amount of toxins in their skin, which is brightly colored to act as a warning. Even then, only 2% of larvae make it to the eft stage. Some larvae have been found in the pitchers of the carnivorous plant Sarracenia purpurea.[7]

Eastern newts eat a variety of prey, such as insects, small mollusks and crustaceans, young amphibians, worms, and frog eggs.

Conservation concerns

Although eastern newts are widespread throughout North America, they, like many other species of amphibians, are increasingly threatened by several factors including habitat fragmentation, climate change, invasive species, over-exploitation, and emergent infectious diseases.[8] Wild eastern newts are known hosts of Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis and Ranavirus. They are also highly susceptible to the newly emergent chytrid fungus Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans.[9]

Gallery

-

Terrestrial juvenile stage ("red eft")

-

Aquatic larval stage

-

Eft near Northfield, Massachusetts

-

Eft navigating over leaves near Thomasville, Alabama

-

Eft on North Fork Mountain in eastern West Virginia

-

Eft seen along a trail in Harriman Park, New York

-

Swollen cloaca and large hind legs in a reproductive adult male

-

Adult female central newt

-

A red-spotted newt among the autumn leaves not far from Bolton, Vermont

References

Citations

- ^ "Notophthalmus viridescens". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T59453A78906143. 2015. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-4.RLTS.T59453A78906143.en.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Marion, Zachary H; Hay, Mark E (2011). "Chemical Defense of the Eastern Newt (Notophthalmus viridescens): Variation in Efficiency against Different Consumers and in Different Habitats". PLoS ONE. 6 (12): e27581. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0027581. PMC 3229496. PMID 22164212.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Phillips, J; Borland, S (1994). "Use of a Specialized Magnetoreception System for Homing by the Eastern Red-Spotted Newt Notophthalmus Viridescens". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 188 (1): 275–91. PMID 9317797.

- ^ a b Brassart, J; Kirschvink, J. L; Phillips, J. B; Borland, S. C (1999). "Ferromagnetic material in the eastern red-spotted newt notophthalmus viridescens". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 202 Pt 22: 3155–60. PMID 10539964.

- ^ Behler, John L.; King, F. Wayne (1979). The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians (Chanticleer Press ed.). New York: Knopf. p. 276. ISBN 978-0-394-50824-5. Retrieved 4 September 2012.

- ^ Santos, J. C; Coloma, L. A; Cannatella, D. C (2003). "Multiple, recurring origins of aposematism and diet specialization in poison frogs". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 100 (22): 12792–7. doi:10.1073/pnas.2133521100. JSTOR 3148039. PMC 240697. PMID 14555763.

- ^ Butler, Jessica L; Atwater, Daniel Z; Ellison, Aaron M (2005). "Red-spotted Newts: An Unusual Nutrient Source for Northern Pitcher Plants". Northeastern Naturalist. 12 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1656/1092-6194(2005)012[0001:rnauns]2.0.co;2. JSTOR 3858498.

- ^ Collins, James P; Storfer, Andrew (2003). "Global amphibian declines: Sorting the hypotheses". Diversity and Distributions. 9 (2): 89–98. doi:10.1046/j.1472-4642.2003.00012.x. JSTOR 3246802.

- ^ Martel, A; Blooi, M; Adriaensen, C; Van Rooij, P; Beukema, W; Fisher, M. C; Farrer, R. A; Schmidt, B. R; Tobler, U; Goka, K; Lips, K. R; Muletz, C; Zamudio, K. R; Bosch, J; Lotters, S; Wombwell, E; Garner, T. W. J; Cunningham, A. A; Spitzen-Van Der Sluijs, A; Salvidio, S; Ducatelle, R; Nishikawa, K; Nguyen, T. T; Kolby, J. E; Van Bocxlaer, I; Bossuyt, F; Pasmans, F (2014). "Recent introduction of a chytrid fungus endangers Western Palearctic salamanders". Science. 346 (6209): 630–1. doi:10.1126/science.1258268. PMC 5769814. PMID 25359973.

Further reading

- Grayson, Kristine L; De Lisle, Stephen P; Jackson, Jerrah E; Black, Samuel J; Crespi, Erica J (2012). "Behavioral and physiological female responses to male sex ratio bias in a pond-breeding amphibian". Frontiers in Zoology. 9 (1): 24. doi:10.1186/1742-9994-9-24. PMC 3478290. PMID 22988835.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Brossman, Kelly H; Carlson, Bradley E; Stokes, Amber N; Langkilde, Tracy (2014). "Eastern Newt (Notophthalmus viridescens) larvae alter morphological but not chemical defenses in response to predator cues". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 92 (4): 279–83. doi:10.1139/cjz-2013-0244.

External links

- Notophthalmus viridescens. Animal Diversity Web.

- Eastern Newt (Notophthalmus viridescens. Checklist of Amphibian Species and Identification Guide. USGS Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center.

- Red-spotted Newt (Notophthalmus viridescens viridescens). Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries.

- Eastern Newt Caresheet and Photos. Caudata Culture.

- Notophthalmus viridescens Species Account. AmphibiaWeb.

- Central Newt on Reptiles and Amphibians of Iowa

- IUCN Red List least concern species

- Amphibians of Canada

- Amphibians of the United States

- Amphibians described in 1820

- Cenozoic amphibians of North America

- Ecology of the Appalachian Mountains

- Extant Pleistocene first appearances

- Fauna of the Great Lakes region (North America)

- Fauna of the Northeastern United States

- Fauna of the Plains-Midwest (United States)

- Fauna of the Southeastern United States

- Newts

- Pleistocene animals of North America

- Pleistocene United States

- Taxa named by Constantine Samuel Rafinesque