James Stark (painter)

James Stark | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Horace Beevor Love (1830), National Portrait Gallery, London | |

| Born | 19 November 1794 |

| Died | 24 March 1859 (aged 64) Camden Town, London |

| Resting place | Rosary Cemetery, Norwich |

| Nationality | English |

| Education | John Crome |

| Known for | Landscape painting |

| Movement | Norwich School of painters |

| Elected | Norwich Society of Artists |

James Stark (19 November 1794 – 24 March 1859) was an English landscape painter. A leading member of the Norwich School of painters, he was elected vice-president of the Norwich Society of Artists in 1828 and became their president in 1829. He had wealthy patrons and was consistently praised by the Norfolk press for his successful London career.

Stark was born in Norwich, the youngest son of an important dye manufacturer, Michael Stark, who is credited with the invention of the dye known as 'Norwich red'. On the completion of his education at Norwich School in 1811, he was apprenticed to John Crome, whose influence on his pupil was profound. His work was exhibited in London as early as 1811 and at the British Institution from 1814–18. In 1814 he moved away from Norwich to London, where he befriended the artist William Collins. In 1819 ill health forced him to return to Norwich, where lived for twenty years, before moving to Windsor in 1840, where he continued to produce landscapes. He returned to London in 1849, residing there until his death in 1859 at the age of 64. He is buried in the Rosary Cemetery in Norwich.

Stark generally worked in oils, although his total output included etchings, watercolours and pencil and chalk drawings. His landscapes paintings often depicting woodland scenes that were pastiches of the seventeenth century Dutch masters. His works during the 1830s were more successful, and displayed a freshness that was previously lacking. In 1834 he published his admired Scenery of the Rivers of Norfolk, which consisted of thirty-six etchings produced by specialist engravers after his own paintings. This ambitious work was well-received at the time, but as with similar works published by other artists, it was financially unsuccessful.

Life

Early life and apprenticeship to Crome

James Stark was born in Norwich on 19 November 1794, the son of Michael Stark (1748–1831) and his wife Jane Ivory. He was christened on 30 November 1794 at the Church of St Michael Coslany, Norwich, close to the family home.[1] James was the youngest son of eight siblings. His father Michael Stark was a Scottish-born dyer who had a considerable literary and scientific background,[2] and who ran his own dyeing business on Duke Street, Norwich.[3] He is credited with a number of innovations in the dyeing industry, including the invention of the formula of 'Norwich red'.[4][2]

James Stark showed a talent for art from an early age. He was educated at Norwich School, where he became friends with John Berney Crome, the son of the artist (and his teacher) John Crome.[5] Two of Stark's pencil drawings were exhibited in Norwich in 1809,[6] and he exhibited for the first time in London in 1811, at the age of seventeen, when his painting A view on King Street river, Norwich was shown at the Royal Academy.[7]

Because of his poor health, which dogged him throughout his life, his initial ambitions to become a farmer were never realised.[8] In 1811 he was apprenticed for three years to John Crome.[9] Two letters from Crome to his teenage pupil survive. One, dated 3 July 1814 and sent to Starks' house in London, contains a reminder to submit work to the Norwich Society of Artists' forthcoming exhibition. The second letter is considered by art historians to be important, as it reveals how Crome was able to impart his knowledge to his pupils.[10][note 1] Amongst other suggestions, the letter encouraged Stark to consider using more "breadth".[2] Crome was a strong influence on Stark, who was his favourite pupil, and Crome's preoccupation with depicting trees and woodland scenes led Stark to produce many such scenes himself.[11][12] He was elected as a member of the Norwich Society of Artists in 1812. He exhibited at the British Institution between 1814 and 1818, winning a prize of £50 in 1818.

Artistic career

In 1814, following the end of his Norwich apprenticeship, Stark moved to London. There he befriended and became influenced by the artist William Collins.[13] In 1817 he became a student at the Royal Academy. The Bathing Place, Morning was sold in 1817 to the Henry Hobart, the Dean of Windsor.[13] For a short period he shared lodgings with the portrait painter Joseph Clover. During this period he began to sell paintings to wealthy patrons: both the Marquis of Stafford and the Countess de Grey bought works from him.[14][9]

After only two years of study in London, debilitating ill health forced him to return to Norwich, where he remained for nearly twenty years, until his final move from the city in 1830.[13][9] There he devoted himself to painting the scenery around the city and executing a series of paintings of Norfolk rivers, which were eventually engraved and published in 1834. Regarded during his lifetime by his friends as one of the leaders of the Norwich School of painters, he was elected Vice-President of the Norwich Society of Artists in 1828 and President in the following year, at a time when the Society was struggling to survive.[13]

In 1840 Stark moved to Windsor, where he lived for ten years.[13] During this period in his life he painted many pictures of the scenery along the Thames and in Windsor Great Park, producing images of trees that revealed his improved understanding of their structure.[15]

Family life and final years

On 7 July 1821 he married Elizabeth Younge Dinmore of King's Lynn.[16] In 1830, he moved to London, taking up residence in Beaumont Row, Chelsea. Elizabeth Stark died in 1834, three years after the birth of their son, Arthur James Stark.[13] He moved back to London in 1849 to further his son's artistic education, residing at Mornington Place, Camden Town. James Stark died in March 1859. His body was interred in the family burial plot in the Rosary Cemetery, Norwich.[13]

Development as an artist

Stark mainly worked in oils, though he was also a watercolourist, and produced drawings in pencil and chalk.[17] He initially followed his teacher John Crome in producing works with soft greys and pinks, in a style similar to that of Crome's Back of the New Mills (c. 1815).[18] His first important success occurred the same year, when he exhibited The Bathing Place – Morning.[9] His Lambeth, looking towards Westminster Bridge (1818), now in the Yale Center for British Art collection in New Haven, Connecticut, provides an indication of Stark's initial technique, which Andrew Hemingway describes as "a fairly broad style comparable with that of his fellow pupils".[9]

Stark's early paintings were followed by landscapes of a repetitive and stylized kind, generally depicting woodland glades, and for which he is generally best known today.[19] These scenes fell into the trap of being "a mere pastiche of the seventeenth formula", containing ochre, red and green pigments to depict scenes containing poorly-drawn trees. Such works were exhibited under the title Landscape. By 1825, the London Magazine was reporting that Stark's subject matter lacked development, tending as he did to base his works on the paintings of seventeenth-century Dutch masters such as Meindert Hobbema and Jacob van Ruisdael.[20]

By the mid-1830s, Stark had moved away from the influence of the Dutch masters and was producing paintings that showed nature less heavily and more freely. These works have more descriptive titles.[21][22] Not all his critics were pleased: the Norfolk Chronicle complained in 1829 of Stark's move away from depicting formulaic scenes towards a greater use of bright colours and more brilliant lighting effects.[23] His work during this period in his artistic career became more successful, according to Hemingway. The numerous sketches of the Norfolk countryside he had previously produced gave his exhibited works a freshness that was previously lacking, and which was more appealing to the critics. Cromer, exhibited at the British Institution in 1837, is a good example of this new kind of work, and shows the influence of his friend William Collins and the Norwich artist John Thirtle. Like many of his later works, it is based on earlier sketchwork.[15]

Like many painters of the Norwich School, Stark produced his own etchings, but these were not exhibited. As they generally lacked a title, they are nowadays difficult to identify and are little known. Geoffrey Searle, in his survey of the etchings produced by the Norwich School, describes Stark's own etchings as "having a distinctive charm".[17] The article on Stark in the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica noted that "his works charm rather by their gentle truth and quietness of manner than by their robustness of view or by their decisiveness of execution".[24]

Exhibitions and publications

James Stark exhibited paintings throughout his working life. The Norwich Society of Artists, which was inaugurated in 1803 and held annual exhibitions almost continuously until 1833, exhibited 105 works by Stark from 1809–32, of which seventy-three were landscapes and four were of marine scenes.[25]

During his career he had many wealthy patrons and was regarded in London as a successful provincial artist.[13] He was consistently praised by the Norfolk press. In 1817, when only twenty-three, he and his friend John Berney Crome had been praised in the Norwich Mercury "for their great and rapid strides".[26] As well as exhibiting in London and Norwich, Stark had his paintings shown in exhibitions as far afield as Glasgow, Edinburgh and Dublin.[13]

Stark wrote an essay On the moral and political influence of the Fine Arts, published in the Norwich Mercury on 26 May 1827, criticising those who were apparently indifferent towards the financial plight of the Norwich Society of Artists.[27]

Subsequent exhibitions of works by Stark include an exhibition held in 1887.[28]

Pupils

Stark taught his own son Arthur, as well as Alfred Priest, Henry Jutsum and Samuel David Colkett, all of whom emerged to become minor artists.[29] Their artistic styles were heavily influenced by their teacher, and none of them produced notable works of art. Arthur James Stark specialised in depicting landscapes and animals, and drew the cattle on a few of his father's pictures.[30][15]

Published works

- Stark, James; Robberds, J.W. (1834). Scenery of the rivers of Norfolk: comprising the Yare, the Waveney, and the Bure, from pictures painted by James Stark, with historical and geological descriptions by J.W. Robberds, Jun. Norwich: John Stacy.[31]

Gallery

-

Cromer (c.1837), Norfolk Museums Collections

-

Lambeth from the River looking towards Westminster Bridge (1818), Yale Center for British Art

-

Woody Landscape, Tate Britain

-

View near the Foundry Bridge (1828)

-

The Forest Oak (c.1843), Norfolk Museums Collections

-

River scene (undated), Art Gallery of New South Wales

-

Sheep Washing at Postwick Grove, Norwich (circa 1822), Yale Center for British Art

-

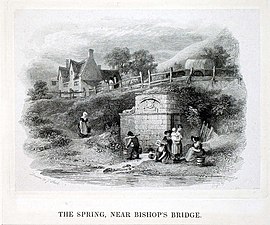

The Spring, near Bishops Bridge (undated), Norfolk Museums Collections

-

Farmhouse at Old Buckhurst, Sussex (1853), National Museums Liverpool

-

Harrison's Wharf, King Street Norwich (undated), Norfolk Museums Collections. The etching is from James Stark's series Scenery of the rivers of Norfolk.

Notes

- ^ Crome published nothing in his lifetime, and so his letter to James Stark is important because of the remarks it contains about being a skilful painter. The letter from Crome to Stark is now held in the British Library (Reference: Add MS 43830 T : Jan 1816)

References

- ^ James Stark in "Parish registers, 1550–1900", FamilySearch ([Archdeacons transcripts for Norwich parishes, 1600–1812 James Stark]).

- ^ a b c Hemingway 1979, p. 52.

- ^ "Norwich, Duke's Palace Bridge – James Stark". Norfolk Heritage Explorer. Norfolk County Council. Retrieved 2 August 2018. Dye Works, Duke's Palace Bridge, a lithograph on paper by Stark depicting his father's dye works in Norwich.

- ^ The Sessional Papers of the House of Lords, in the Session 1840, p. 304.

- ^ Cundall 1920, p. 25.

- ^ Rajnai & Stevens 1976, p. 87.

- ^ Graves 1906, pp. 239–240.

- ^ Walpole 1997, pp. 34–5.

- ^ a b c d e Hemingway 1979, p. 55.

- ^ Moore 1985, p. 21.

- ^ Searle 2015, pp. 55–8.

- ^ Searle 2015, p. 112.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Moore 1985, pp. 32–3.

- ^ Moore 1985, p. 49.

- ^ a b c Hemingway 1979, p. 60.

- ^ Mottram 1931, p. 184.

- ^ a b Searle 2015, p. 55.

- ^ Moore 1985, p. 27.

- ^ Hemingway 1979, p. 56.

- ^ Moore 1985, p. 32.

- ^ Moore 1985, p. 29.

- ^ Hemingway 1979, pp. 57–8.

- ^ Hemingway 1979, p. 59.

- ^ Chisholm 1911.

- ^ Rajnai & Stevens 1976, pp. 3, 144.

- ^ Moore 1985, p. 19.

- ^ Moore 1985, p. 14.

- ^ "The Stark Exhibition". Norwich Mercury. Norwich. 29 June 1887. Retrieved 27 July 2018. (subscription required)

- ^ Cust, Dictionary of National Biography, 1885–1900, Volume 30.

- ^ Moore 1985, pp. 121, 128, 130.

- ^ "Scenery Of The Rivers Of Norfolk, Comprising The Yare, The Waveney, And The Bure. From Pictures Painted By James Stark, With Historical And Geological Descriptions By J.W. Robberds, Jun. Esq". Royal Academy. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

Bibliography

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Stark, James". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 15 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 797.

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1898). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 54. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 106–7.

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1892). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 30. London: Smith, Elder & Co. p. 233.

- Cundall, H. M. (1920). Holme, Geoffrey C. (ed.). The Norwich School. London, Paris, New York: The Studio Ltd. ND471.N6 H6.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|lay-source=ignored (help) - Graves, Algernon (1906). "Stark, James". The Royal Academy of Arts. A Complete Dictionary of Contributors and their work from its foundation in 1769 to 1904. Vol. Vol. VII Sacco to Tofano. London: Henry Graves & Co and George Bell & Sons.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Hemingway, Andrew (1979). The Norwich School of Painters, 1803–33. Oxford: Phaidon. ISBN 9780714820019.

- Moore, Andrew W. (1985). The Norwich School of Artists. HMSO/Norwich Museums Service.

- Mottram, R.H. (1931). John Crome of Norwich. London: John Lane The Bodley Head Limited.

- Rajnai, Miklos; Stevens, Mary (1976). The Norwich Society of Artists, 1805-1833: a dictionary of contributors and their work. Norfolk Museums Service for the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art.

- Searle, Geoffrey R. (2015). Etchings of the Norwich School. Norwich: Lasse Press. ISBN 978-0-9568758-9-1.

- Walpole, Josephine (1997). Art and Artists of the Norwich School. Woodbridge: Antique Collectors' Club. ISBN 1-85149-261-5.

- "Library of the Fine Arts: Or, Repertory of Painting, Sculpture, Architecture, and Engraving". Library of the Fine Arts. Vol. 3. London: M. Arnold. 1832.

- The Sessional Papers Printed by Order of the House of Lords in the Session 1840 (volume 37). London. 1997.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

External links

- 94 artworks by or after James Stark at the Art UK site

- 55 works relating to James Stark in the British Museum

- 93 works relating to James Stark in the Norfolk Museums Collections

- Information about James Stark from the ArtCyclopedia website

- 9 works by James Stark in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

- 2 works by James Stark at the Tate Museum, London

- 11 works by James Stark at the Yale Center for British Art