Eric Kennington

Eric Kennington | |

|---|---|

An Infantryman Resting (1916) | |

| Born | Eric Henri Kennington 12 March 1888 Chelsea, London, England, UK |

| Died | 13 April 1960 (aged 72) |

| Nationality | British |

| Education | Lambeth School of Art |

| Known for | Painting, sculpture |

Eric Henri Kennington RA (12 March 1888 – 13 April 1960) was an English sculptor, artist and illustrator, and an official war artist in both World Wars.[1]

As a war artist, Kennington specialised in depictions of the daily hardships endured by soldiers and airmen. In the inter-war years he worked mostly on portraits and a number of book illustrations. The most notable of his book illustrations were for T. E. Lawrence's Seven Pillars of Wisdom. Kennington was also a gifted sculptor, best known for his 24th East Surrey Division War Memorial in Battersea Park, for his work on the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon and for the effigy of Lawrence at Wareham in Dorset.[2]

Biography

Early life

Kennington was born in Chelsea, London, the second son of the genre and portrait painter, Thomas Benjamin Kennington (1856–1916), a founder member of the New English Art Club. He was educated at St Paul's School and the Lambeth School of Art.[1] Kennington first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1908. At the International Society in April 1914 Kennington exhibited a series of paintings and drawings of costermongers which sold well and allowed him to set up a studio off Kensington High Street in London.[3]

First World War

At the start of World War I, Kennington enlisted with the 13th (Kensington) Battalion London Regiment on 6 August 1914.[4] He fought on the Western Front, but was wounded in January 1915 and evacuated back to England. Kennington was injured while attempting to clear a friend's jammed rifle and he lost one toe and was fortunate not to lose a foot due to infection.[5] He spent four months in hospital before being discharged as unfit in June 1915.[3] During his convalescence, he spent six months painting The Kensingtons at Laventie, a group portrait of his own infantry platoon, Platoon No 7, 'C' Company. Kennington himself is the figure third from the left, wearing a balaclava.[6][7] When exhibited in the spring of 1916, its portrayal of exhausted soldiers caused a sensation. Painted in reverse on glass, the painting is now in the Imperial War Museum and was widely praised for its technical virtuosity, iconic colour scheme, and its "stately presentation of human endurance, of the quiet heroism of the rank and file".[8]

Kennington visited the Somme in December 1916 as a semi-official artist visitor before, back in London, producing six lithographs under the title Making Soldiers for the Ministry of Information's Britain's Efforts and Ideals portfolio of images which were exhibited in Britain and abroad and were also sold as prints to raise money for the war effort.[9] In May 1917 he accepted an official war artist commission from the Department of Information. Kennington was commissioned to spend a month on the Western Front but he applied for numerous extensions and eventually spent seven and a half months in France. Kennington was originally based at the Third Army Headquarters and would spend time at the front lines near Villers-Faucon. Later during this tour, his friend William Rothenstein was also appointed as a war artist and they worked together at Montigny Farm and at Devise on the Somme, where they often came under shell-fire.[5] Kennington spent most of his time painting portraits, which he was happy to do, but became increasingly concerned about his lack of access to the front line and that the official censor was removing the names of his portrait subjects. Although Kennington was among the first of the official war artists Britain sent to France, he was not afforded anything like the status and facilities that the others, in particular William Orpen and Muirhead Bone enjoyed.[10] Whereas Kennington was working for neither salary nor expenses and had no official car or staff, Orpen was given the rank of major, had his own military aide, a car and driver, plus, at his own expense, a batman and assistant to accompany him.[8] Kennington could be aggressive and irritable and at times complained bitterly about his situation, claiming he must have been the cheapest artist employed by the Government and that "Bone had a commission and Orpen had a damned good time".[5]

During his time in France, Kennington produced 170 charcoal, pastel and watercolours before returning to London in March 1918.[11] Whilst in France in 1918, Kennington was admitted to a Casualty Clearing Station at Tincourt-Boucly to be treated for trench fever. There he made a number of sketches and drawings of men injured during the bombardment that preceded the German 1918 Spring Offensive. Some of these drawings became the basis of the completed painting Gassed and Wounded.[12][13]

Throughout June and July 1918 an exhibition of Kennington's work, "The British Soldier", was held in London and received great reviews and some public acclaim. Despite this, Kennington was unhappy in his dealings with Department of Information, mainly concerning the censoring of his paintings, and he resigned his war artist commission with the British. In November 1918 Kennington was commissioned by the Canadian War Memorials Scheme to depict Canadian troops in Europe. That month he returned to France as a temporary first lieutenant attached to the 16th Battalion (Canadian Scottish), CEF. The eight months Kennington spent in Germany, Belgium and France, working for the Canadians, resulted in some seventy drawings.[3][11]

1920s

At an exhibition of his war art in London, Kennington met T. E. Lawrence who became a great influence on him. Kennington spent the first half of 1921 travelling through Egypt, Jordan, Syria, Lebanon and Palestine drawing portraits of Arab subjects. These were displayed at an exhibition in October 1921 and some of the drawings were used as illustrations for Lawrence's The Seven Pillars of Wisdom, for which Kennington worked as the art editor. Years later, in 1935, Kennington was to serve as one of the six pallbearers at Lawrence's funeral. In 1922 Kennington began to experiment with stone carving and soon undertook his first public commission, the War Memorial to the 24th Division in Battersea Park which was unveiled in October 1924. The same month he held his first exhibition which focused on sculpture rather than his paintings and drawings, although he continued to accept portrait commissions and other work. These included the original dust jacket design for George Bernard Shaw's book The Intelligent Woman's Guide to Socialism and Capitalism.[11]

During the 1920s, Kennington worked on a frieze for the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine intended to be situated above the School's Keppel Street entrance. The stone panel depicts a mother and child being protected from a fanged serpent by a nude, bearded, knife-wielding father. However, due to the prominent display of male genitalia, the trustees of the School would not allow it to be placed above the School's entrance unless Kennington added a well placed loin cloth. He refused and the work was placed above the entrance of the library where it remains.[14] In 1966, when the library's mezzanine floor was constructed, a large crack formed and was subsequently painted to disguise the damage.

In 1922, Kennington married Edith Cecil, daughter of Lord Francis Horace Pierrepont Cecil (who was second son of William Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Exeter), with whom he had a son and a daughter. Edith, who was already married to William Hanbury-Tracy (5th Baron Sudeley), fell in love with Kennington while he was painting her husband's picture. They both remained good friends with Edith's ex-husband.

1930s

Throughout the late 1920s and the 1930s, Kennington produced a number of notable public sculptures,

- September 1926; a bronze bust of T. E. Lawrence which in 1936 was unveiled in the crypt of St Paul's Cathedral

- July 1929; three nine foot high stone figures of British soldiers for the Imperial War Graves Commission Memorial to the Missing, the Soissons Memorial

- 1931; statue of Thomas Hardy which was unveiled in Dorchester by J. M. Barrie on 2 September that year

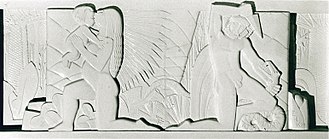

- September 1931; a series of five allegorical reliefs, entitled Love, Jollity, Treachery, War and Life & Death, on the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre building in Stratford on Avon.[15]

- December 1936; the Comet Inn pillar, Hatfield, Hertfordshire

- 1937-1939; a life-sized effigy, in Portland stone, of T. E. Lawrence for St Martin's Church, Wareham, Dorset.[16]

Second World War

By November 1938 Kennington was certain that another World War was inevitable and he approached the Home Office with a proposal to establish a group to design camouflage schemes for large public buildings. Alongside Richard Carline, Leon Underwood and others he worked in a section attached to the Air Raid Precautions Department of the Home Office until war broke out.[11]

At the start of the Second World War, Kennington produced a number of pastel portraits of Royal Navy officers for the War Artists' Advisory Committee (WAAC), on short-term contracts. These portraits were among the highlights of the first WAAC exhibition at the National Gallery in the summer of 1940. Kennington also painted a portrait of Admiral of the Fleet Sir Dudley Pound. Pound was seriously ill when Kennington sketched him and although the Admiralty were pleased with the image they refused permission for it to be displayed until after Pound died in October 1943.[11] Kennington next painted several younger seamen, several of whom had survived shipwrecks. By May 1940 Kennington was frustrated by WAAC's lack of urgency in putting forward subjects for him to paint and resigned his contract. He joined the newly formed Home Guard and was given command of a six-man section at Ipsden.

In August 1940 the WAAC Committee offered him a full-time salaried contract to work for the Air Ministry, which he accepted. Among Kennington's first RAF portraits was one of Squadron Leader Roderick Learoyd VC. The sitting took place on the afternoon of 7 September 1940 at the Air Ministry building in London and was interrupted by an air-raid siren which, after Learoyd had looked outside to see where the German planes were heading, the two men ignored.[11] By March 1941 Kennington was based at RAF Wittering, a Night Fighter base. Here, as well as portraits Kennington produced some more imaginative works, including In the Flare Path and Stevens' Rocket.[17] Kennington next spent some time at Bomber Command bases in Norfolk before moving to RAF Ringway near Manchester where the Parachute Regiment were training. Although over-age, Kennington undertook at least one parachute jump at Ringwood. In September 1941 he self-published an illustrated booklet, Pilots, Workers, Machines to great acclaim.[11]

Kennington continued to travel around Britain to produce hundreds of portraits of Allied flight crew and other service personnel until September 1942 when he resigned his commission because he felt that WAAC were failing to capitalise on the propaganda value of his work in their publications and posters.[18][19] Some 52 of Kennington's RAF portraits were published in a 1942 WAAC book, Drawing the RAF.[20] This was followed in 1943 with Tanks and Tank Folk, illustrations from Kennington's time with the 11th Armoured Division near Ripon in Yorkshire. In 1945 Kennington supplied the illustrations for Britain's Home Guard by John Brophy.[21] Darracott and Loftus describe how in both wars "his drawings and letters show him to be an admirer of the heroism of ordinary men and women", an admiration which is particularly notable in the poster series "Seeing it Through", with poems by A. P. Herbert, a personal friend of his.

Post-war career

By the time the war ended over forty of the RAF pilots and aircrew whose portraits Kennington had painted had been killed in action. Kennington resolved to create a suitable memorial for them and over the next ten years, whilst also working on sculpture and portrait commissions, he patiently carved 1940, a column with the head of an RAF pilot topped by the Archangel Michael with a lance slaying a dragon.[11] In 1946 Kennington was appointed as the official portrait painter to the Worshipful Company of Skinners. Over the next five years he produced nine pastel portraits for the company, which were highly praised when shown at the Royal Academy. In 1951 Kennington became an associate member of the Academy and was elected a full academician in 1959.[22] His last work, which was completed on his death by his assistant Eric Stanford, was a stone relief panel that decorates the James Watt South Building in the University of Glasgow.

Kennington is buried in the churchyard in Checkendon, Oxfordshire, where he was churchwarden, and is commemorated on a memorial in Brompton Cemetery, London.

References

- ^ a b Tate. "Artist biography: Eric Kennington". Tate Britain. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- ^ Ian Chilvers (2004). The Oxford Dictionary of Art. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-860476-9.

- ^ a b c Jonathan Black (19 January 2012). "Portraits like Bombs:Eric Kennington and the Second World War". National Army Museum. Retrieved 21 July 2015..

- ^ 'The Kensingtons at Levantie', 'Kensington Express' 16 June 1916, P.4

- ^ a b c Merion Harries & Susie Harries (1983). The War Artists, British Official War Art of the Twentieth Century. Michael Joseph, The Imperial War Museum & the Tate Gallery. ISBN 0-7181-2314-X.

- ^ Imperial War Museum. "The Kensingtons at Laventie". Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ Richard Slocombe (Senior art curator IWM) (30 August 2013). "Art of war:The Kensingtons at Laventie". The Telegraph. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- ^ a b Paul Gough (2010). A Terrible Beauty: British Artists in the First World War. Sansom and Company. ISBN 978-1-906593-00-1.

- ^ Mari Gordon (Series Editor) (2014). The Great War: Britain's Efforts and Ideals. National Museum of Wales. ISBN 9780720006278.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Imperial War Museum (2014). "Kennington, Eric 1917-1918". Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Jonathan Black (2011). The Face of Courage Eric Kennington, Portraiture and the Second World War. Philip Wilson Publishers. ISBN 978-0-85667-705-2.

- ^ Imperial War Museum. "Search the Collection, Gassed and Wounded". Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- ^ Sandy Nairne (8 November 2018). "Sandy Nairne on Eric Kennington's 'Gassed and Wounded'". Art UK. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ Jonathan Black (2002). The Sculpture of Eric Kennington. Lund Humphries Publishers Ltd. p. 41. ISBN 0853318239.

- ^ HCG Matthew & Brian Harrison (Editors) (2004). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Vol 31 (Kebell-Knowlys). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-861381-4.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Richard Knowles (1991). "Tale of an 'Arabian knight': the T. E. Lawrence effigy". Church Monuments. 6: 67–76.

- ^ Imperial War Museum. "Stevens' Rocket". Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ^ Brain Foss (2007). War paint: Art, War, State and Identity in Britain, 1939-1945. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10890-3.

- ^ Imperial War Museum. "War artists archive - Eric Kennington Part 1". Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- ^ Matt Brosnan (2014). "This War Artist Drew Stunning Portraits of RAF Pilots in the Second World War". Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ^ Richard Moss (13 July 2011). "Eric Kennington's Portraits of the British at War at the RAF Museum, London". Culture24. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- ^ "Eric Kennington, R.A." Royal Academy. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

External links

- 44 artworks by or after Eric Kennington at the Art UK site

- 1888 births

- 1960 deaths

- 20th-century British sculptors

- 20th-century English painters

- English male painters

- Alumni of the Lambeth School of Art

- British Army personnel of World War I

- British Home Guard soldiers

- British war artists

- Camoufleurs

- English illustrators

- English portrait painters

- English sculptors

- English male sculptors

- London Regiment soldiers

- Painters from London

- People educated at St Paul's School, London

- People from Chelsea, London

- Royal Academicians

- World War I artists

- World War II artists