Plan of Ayala

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (January 2010) |

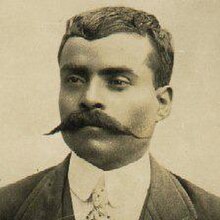

The Plan of Ayala (Spanish: Plan de Ayala) was a document drafted by revolutionary leader Emiliano Zapata during the Mexican Revolution.[1] In it, Zapata denounced President Francisco I. Madero for his perceived betrayal of the revolutionary ideals, embodied in Madero's Plan de San Luis Potosí, and set out his vision of land reform.[2] The Plan was first proclaimed on November 28, 1911 in the town of Ayala, Morelos, and was later amended on June 19, 1914.[2][3] John Womack calls the Plan the Zapatistas' "Sacred Scripture".[4]

Background

Emiliano Zapata had supported Francisco I. Madero against the regime of Porfirio Díaz. Díaz was deposed and Madero was elected president. He took office on June 7, 1911, and soon after had a meeting with Zapata where he demanded the disarmament of Zapata's army as a precondition for discussion of agrarian reform. Unsatisfied, Zapata returned to Morelos arguing that if the people were not able to achieve justice after rising in arms, there was no guarantee they would achieve it without them. Finally, after Madero's appointment of a governor who supported plantation owners and his failure to settle the land issue to Zapata's satisfaction, Zapata mobilized his army again.

The Plan

The Plan was drafted with the help of local schoolteacher—and Zapata's mentor—Otilio Montaño Sánchez.[1] It detailed Zapata's ideology and vision succinctly in the cry ""Reforma, Libertad, Justicia y Ley!" ("Reform, Freedom, Justice and Law!"),[5] later (after Zapata's death) shortened to "Tierra y Libertad!"[6] ("Land and Freedom!", a phrase first used by Ricardo Flores Magón as the title for one of his books).[7]

The Plan contains fifteen points, summarized here:

- Zapata denounces Madero's revolution, claiming that his only motivations were to further his own power. Zapata goes on to state that Madero is not fulfilling the promises of his revolution, is keeping much of Díaz's government intact and is suppressing the people who demand fulfillment of promises with violence. Zapata goes on to declare Madero incapable of ruling and calls on all Mexicans to continue the revolution.[8]

- Zapata states that Madero is no longer recognized as president and states that they are attempting to overthrow him.[8]

- General Pascual Orozco is nominated as Chief of the Revolution and, if he does not accept, Zapata nominates himself.[8]

- A declaration from the Junta of the State of Morelos that the following points are additions to the plan of San Luis Potosí, and that it makes itself the defender of the plan and its principles until victory or death.[8]

- The Junta of the State of Morelos will not compromise until Madero and the remainders of Díaz's government are overthrown.[8]

- The property taken from the people by “landlords, científicos, or bosses” will be returned to the citizens who have the titles to that property. Tribunals will be held after revolutionary victory to determine who the land belongs to;[8] "The possession of said properties shall be kept at all costs, arms in hand. The usurpers who think they have a right to said goods may state their claims before special tribunals to be established upon the triumph of the Revolution." [9]

- Because the vast majority of Mexican citizens own little to no land, one third of property of Mexican monopolies will be taken and redistributed to villages and individuals without land;[8]"That to the pueblos (villages) there be given what in justice they deserve as to lands, timber, and water, which [claim] has been the origin of the present Counterrevolution" [10]

- In addition to the previous point, owners of monopolies that oppose this plan will lose the remaining two thirds of their properties. These properties will be used as war reparations and as payment to the victims of the struggle of the revolution.[8]

- To enforce the previous two points, the current forms of nationalization laws will be used.[8]

- The members of Madero's revolution that supported the plan of San Luis Potosí but oppose this plan will be considered traitors and punished.[8]

- Expenses of war will be taken as the plan of San Luis Potosí specifies.[8]

- After revolutionary victory, the Junta of the revolutionary chiefs will select an interim president who will run elections afterward.[8]

- After revolutionary victory, the revolutionary chiefs of each state will select, in Junta, a governor for the state that will run elections to organize public powers. This is done to avoid appointment of officials, which often works against the public.[8]

- Zapata calls for Madero and other dictatorial parts of the government to resign, and threatens them with death if they do not.[8]

- Zapata calls on Mexicans to rise up against Madero, once again denouncing him and his ability to govern; "Mexicans: consider that the cunning and bad faith of one man is shedding blood in a scandalous manner, because he is incapable of governing; consider that his system of government is choking the fatherland and trampling with the brute force of bayonets on our institutions..." [8]

The June 1914 amendment was prompted by Pascual Orozco's alliance with the Victoriano Huerta regime and therefore betrayal of the revolutionary movement. This shift in alliances forced Zapata to become head of the Revolution. The amendment ratified the original intent of the Plan and called for a continuation of the conflict until the overthrow of Victoriano Huerta —who had ordered Madero's murder—and the establishment of a government loyal to the principles of the Plan.

Aftermath

The Plan raised Zapata's profile and support from the peasantry in the Mexican South, as reflected by the increased membership to his Ejército Libertador del Sur ("Liberation Army of the South"). Allied with northern revolutionary armies, under Venustiano Carranza and Pancho Villa they were able to depose Huerta and bring a degree of order to the country, albeit temporary. Zapata quickly came to be in disagreement with Carranza and his Constituent Congress and took up arms once again. Carranza ultimately put a bounty on Zapata's head, resulting in his assassination on April 10, 1919.

However, Zapata's successor as a leader of the Army of the South, was able to strike an agreement with Carranza's successor Álvaro Obregón about an extensive agrarian reform in Morelos, in exchange for support for Obregon's revolt in 1920. Much of the reform was also carried out during Obregón's presidency - albeit only in Morelos.[11]

See also

References

- ^ a b Peter E. Newell, "Zapata of Mexico", Black Rose Books Ltd., 1997, pg

- ^ a b Robert P. Millon, "Zapata: The Ideology of a Peasant Revolutionary", International Publishers Co, 1995, pg. 60, [1]

- ^ Guillermo de la Peña, "A legacy of promises: agriculture, politics and ritual in the Morelos highlands of México", Manchester University Press ND, 1982, pg. 63, [2]

- ^ "Plan of Ayala". World Digital Library. 1911-11-25. Retrieved 2013-06-27.

- ^ Donald Clark Hodges, "Mexican anarchism after the revolution", University of Texas Press, 1995, pg. 15, [3]

- ^ John Noble, "Mexico, Volume 10", Lonely Planet, 2000, pg. 237

- ^ Letizia Argenteri, "Tina Modotti: between art and revolution", Yale University Press, 2003, pg. 101, [4]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Plan de Ayala". users.pop.umn.edu. Retrieved 2016-11-20.

- ^ Wasserman, Mark (2012). The Mexican Revolution: A Brief History with Documents. Boston: Bedford/St.Martin's. pp. 37–39. ISBN 978-0-312-53504-9.

- ^ Womack Jr., John (1968). Zapata and the Mexican Revolution. New York: Vintage. p. 394.

- ^ Womack, John: Zapata and the Mexican revolution, New York 1968

External links

- Text of the Plan de Ayala (in English)