Carlsbad Programme

| Karlsbader Programm | |

|---|---|

| Presented | 24 April 1938 |

| Location | Karlsbad |

| Author(s) | Konrad Henlein |

| Media type | Speech |

| Purpose | Demand of complete equality between the Sudeten Germans and the Czech people, self-governance and the legal recognition of the Sudeten Germans |

The Karlsbader Programm (Template:Lang-cs) was an eight-point series of demands presented by Konrad Henlein,[1] the leader of the Sudeten German Party (SdP), to the government of the First Czechoslovak Republic on 24 April 1938 in Karlsbad (Modern-day Karlovy Vary).[1] The Karlsbader Programm demanded complete equality between the Sudeten Germans and the Czech people, self-government and the legal recognition of the Sudeten Germans.[2][3] Following pressure from Nazi Germany, Britain and France during the Sudeten crisis of 1938, the President of Czechoslovakia, Edvard Beneš, gave in to the demands of the Sudeten Germans.[4]

Background

Following the end of the First World War and the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Czechoslovak Republic emerged on the territory of the modern-day Czech Republic, Slovakia and Ukraine. The territory of the newly formed state included the predominantly German-speaking Sudetenland, however, they represented a minority within the state as a whole.[5]

The Sudeten Germans did not want to belong to a Czechoslovak state after the First World War, because they were used to being part of the Habsburg Monarchy and they did not suddenly want to be a minority in a state of Czechs and Slovaks. The new constitution was worked out without them and they were not consulted about whether they wished to be citizens of Czechoslovakia. Although the constitution of Czechoslovakia guaranteed equality for all citizens, there was a tendency among political leaders to transform the country "into an instrument of Czech and Slovak nationalism" and the Sudeten Germans believed they were not granted enough rights as a minority group.[6][7] Some progress was made to integrate the Germans and other minorities, but they continued to be under-represented in the government and the army.[7]

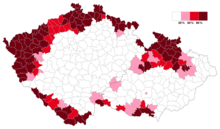

During the Great Depression the highly industrialized and export-oriented regions populated by the German minority, together with other peripheral regions of Czechoslovakia, were hurt by the economic depression more than the interior of the country which was mainly inhabited by Czech and Slovak populations.[8] By 1936, 60 percent of the unemployed people in Czechoslovakia were Germans.[9] The Sudeten Germans were represented by parties from across the political spectrum. German nationalist sentiment was strong in the Sudetenland from the early years of the republic and there was strong calls for autonomy and even union with Germany and Austria. The high unemployment, as well as the imposition of Czech in schools and all public spaces, made people more open to populist and extremist movements such as fascism, communism, and German irredentism. In these years, the parties of German nationalists and later the Sudeten German Party (SdP) with its radical demands gained immense popularity among Germans in Czechoslovakia.

The Sudeten German Party (SdP) was formed in 1933 by Konrad Henlein with the merger of the German National Socialist Workers' Party (Czechoslovakia) and the German National Party after these parties were outlawed. The party represented many of the German nationalist positions, which approximated to those of Nazi Germany. Historians differ as to whether the SdP was from its beginning a Nazi front organization, or evolved into one.[6][10] The Sudeten German Party was "militant, populist, and openly hostile" to the Czechoslovakian government and soon captured two-thirds of the vote in districts with a heavy German population.[6][7] By 1935, the SdP was the second largest political party in Czechoslovakia as German votes concentrated on this party while Czech and Slovak votes were spread among several parties.[6]

Declaration of demands

Immediately after the Anschluß of Austria into the Third Reich in March 1938, Adolf Hitler made himself the advocate of ethnic Germans living in Czechoslovakia, triggering the Sudeten Crisis. Henlein met with Hitler in Berlin on 28 March 1938, where he was instructed to raise demands unacceptable to the Czechoslovak government led by president Edvard Beneš and the following month the SdP began agitating for autonomy. On 24 April 1938, at an SdP party congress, Henlein declared the Karlsbader Programm and adopted the eight-point plan.[11] The Karlsbader programm demanded autonomy and self-government for Germans living in Czechoslovakia.[10]

List of demands

The following demands of the Karlsbader Programm was declared and adopted at an Sudeten German Party (SdP) party congress on 24 April 1938 in the city of Karlsbad (Modern-day Karlovy Vary) by the leader of the SdP party Konrad Henlein:[11][12]

- The recognition of full equality and equality with the Czech people.

- Recognition of the ethnic group as a legal entity to safeguard its equal status in the state.

- Establishment and recognition of the German settlement area.

- Establishment of a German self-government in the German settlement area in all areas of public life, concerning the interests and affairs of the German ethnic group.

- Creation of legal protection for those nationals living outside the closed settlement area of their nationality.

- Elimination of the injustice inflicted upon the Sudeten Germans since 1918 and reparations for the damages they have suffered.

- Recognition and implementation of the principle that the public employees within the German territory are German.

- Full freedom of the right to declare a German nationality and to the German way of life, view and ideology.

Aftermath

The Czechoslovak government responded by rejecting the demands but stated that it was willing to provide more minority rights to the German minority but was initially reluctant to grant them autonomy.[10]

As the previous appeasement of Hitler had shown, the governments of both France and Britain were intent on avoiding war. The French government did not wish to face Germany alone and took its lead from Britain's Conservative government of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. Chamberlain considered the Sudeten German grievances justified and believed Hitler's intentions were limited. Both Britain and France, therefore, advised Czechoslovakia to accede to Germany's demands. Beneš resisted and on 19 May initiated a partial mobilization in response to possible German invasion. On 20 May, Hitler presented his generals with a draft plan of attack on Czechoslovakia codenamed Operation Green. Ten days later, Hitler signed a secret directive for war against Czechoslovakia, to begin not later than the 1 October.[11] In the meantime, the British government demanded that Beneš request a mediator. Not wishing to sever his government's ties with Western Europe, Beneš reluctantly accepted. The British appointed Lord Runciman and instructed him to persuade Beneš to agree to a plan acceptable to the Sudeten Germans.[13]

During August, the German press was full of stories alleging Czechoslovak atrocities against the Sudeten Germans, with the intention of forcing the Western Powers into putting pressure on the Czechoslovaks to make concessions.[11] Hitler hoped the Czechoslovaks would refuse and that the Western Powers would then feel morally justified in leaving the Czechoslovaks to their fate.[11] In August, Germany sent 750,000 soldiers along the border of Czechoslovakia officially as part of army maneuvers.[10][11] On 4 or 5 September[13] Beneš submitted the Fourth Plan, granting nearly all the demands of the Munich Agreement. The Sudeten Germans were not intent on conciliation and were under instructions from Hitler to avoid a compromise,[11] and after the SdP held demonstrations that provoked police action in Ostrava on 7 September in which two of their parliamentary deputies were arrested,[13] the Sudeten Germans used this incident and false allegations of other atrocities as an excuse to break off further negotiations.[11][13]

On 12 September Hitler made a speech at a Nazi Party rally in Nuremberg on the Sudeten crisis in which he condemned the actions of the government of Czechoslovakia.[10] Hitler denounced Czechoslovakia as being a fraudulent state that was in violation of international law's emphasis of national self-determination and accused President Beneš of seeking to gradually exterminate the Sudeten Germans.[14] Hitler stated that he would support the right of the self-determination of fellow Germans in the Sudetenland.[14]

On 13 September, after internal violence and disruption in Czechoslovakia ensued, Chamberlain asked Hitler for a personal meeting to find a solution to avert a war.[13] The two met at Hitler's residence in Berchtesgaden on 15 September and agreed to the cession of the Sudetenland; three days later, French Prime Minister Édouard Daladier did the same. No Czechoslovak representative was invited to these discussions.[15] On the same day, Hitler met with Chamberlain and demanded the swift takeover of the Sudetenland by the Third Reich under threat of war. The Czechs, Hitler claimed, were slaughtering the Sudeten Germans. Chamberlain referred the demand to the British and French governments; both accepted. The Czechoslovak government resisted, arguing that Hitler's proposal would ruin the nation's economy and ultimately lead to German control of all of Czechoslovakia. The United Kingdom and France issued an ultimatum and on 21 September, Czechoslovakia capitulated.[16]

With no end in sight to the dispute, Chamberlain appealed to Hitler for a conference. On 28 September, Hitler met with the chiefs of governments of France, Italy and Britain in Munich. The Czechoslovak government was neither invited nor consulted. On 29 September, the Munich Agreement was signed by Germany, Italy, France, and Britain. The Czechoslovak government capitulated on 30 September and agreed to abide by the agreement. The Munich Agreement stipulated that Czechoslovakia must cede Sudeten territory to Germany. German occupation of the Sudetenland would be completed by 10 October.[17]

See also

- Munich Agreement

- German occupation of Czechoslovakia

- Sudetenland

- Areas annexed by Nazi Germany

- Germans in Czechoslovakia (1918–1938)

References

- ^ a b "Karlovy Vary program". District Landskron (in German). Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- ^ Michael Behnen and Gerhard Taddey (ed.): Encyclopedia of German History. Events, institutions, persons. From the beginning to the capitulation 1945. 3., revised edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 1998, ISBN 3-520-81303-3 , p. 652.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2017-12-13. Retrieved 2019-08-18.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Zayas, Alfred Maurice de: Die Nemesis von Potsdam. Die Anglo-Amerikaner und die Vertreibung der Deutschen, überarb. u. erweit. Neuauflage, Herbig-Verlag, München, 2005.

- ^ Helmut Altrichter, Walter L. Bernecker, 2004: The History of Europe in the 20th Century. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart.

- ^ a b c d Douglas, R. M. (2012), Orderly and Humane, New Haven: Yale University Press

- ^ a b c Vaughan, David (12 February 2002). "HITLER'S FIFTH COLUMN". Radio Praha. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- ^ Kárník, Zdeněk. České země v éře první republiky (1918–1938). Díl 2. Praha 2002.

- ^ Douglas, pp. 7-12

- ^ a b c d e Eleanor L. Turk. The History of Germany. Westport, Connecticut, USA: Greenwood Press, 1999. ISBN 9780313302749. Pp. 123.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Noakes, J.; Pridham, G. (2010) [2001]. Nazism 1919–1945: Foreign Policy War, and Racial Extermination. 2 (2nd ed.). Devon: University of Exeter Press.

- ^ "Karlsbader Programm". kreis-landskron.de.

- ^ a b c d e Bell, P. M. H. (1986). The Second World War in Europe. Harlow, Essex: Longman.

- ^ a b Adolf Hitler, Max Domarus. The Essential Hitler: Speeches and Commentary. Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, 2007. ISBN 9780865166271.

- ^ Santi Corvaja, Robert L. Miller. Hitler & Mussolini: The Secret Meetings. New York, New York, USA: Enigma Books, 2008. ISBN 9781929631421.

- ^ Third Axis Fourth Ally by Mark Axworthy

- ^ Gilbert, Martin; Gott, Richard (1967). The Appeasers. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Bibliography

- Behnen, Michael; Taddey, Gerhard (1998). Encyclopedia of German History. Events, institutions, persons. From the beginning to the capitulation 1945. Vol. 3. Kröner, Stuttgart. ISBN 3-520-81303-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)