Ceintures de Lyon

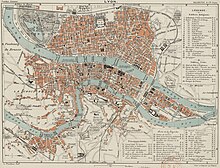

The ceintures de Lyon ("Belts of Lyon") were a series of fortifications built between 1830 and 1890 around the city of Lyon, France to protect the city from foreign invasion.

The belts comprised two defensive barriers that included forts, lunettes, ramparts, batteries, and other defensive structures. Many of these structures proved to be ineffective in war due to advancement in weapon technology and the evolution of attack strategies at the time. Some of the fortifications of the ceintures de Lyon have been destroyed, though many remain today.

History

After the July Revolution in 1830 and the end of the Bourbon monarchy, the government feared a new war. Austria was seen as the major threat to France at the time, and so protecting the east and south-east borders became a priority.[1][2]

Construction of the first belt

In 1830 the maréchal de camp, Hubert Rohault de Fleury, commenced a project designed by military engineer Baron Haxo. With a budget of 10,000,000 francs (approximately €67,000,000 as of 2015) allocated for Lyon between 1831 and 1839,[3] this first project included the restoration of the fortifications between Croix Rousse and Fourvière; the construction of two forts on the plateau of Caluire (Fort de Montessuy and Fort de Caluire, connected by the Enceinte de Caluire), facing the Dombes; closing access to the Presqu'île by the construction of a south-facing building; building two forts – Fort de la Duchère and Fort de Grange Blanche – to protect access routes towards Paris and Auvergne.[4][5]

The fortification of the city is divided into three sectors: The north was protected by the wall of Croix-Rousse and the structures between the Rhône and the Saône. The command was situated at fort de Montessuy. The west was covered by the hillfort of Fourvière and the associated forts of Vaise at Sainte-Foy. The command was situated at fort Saint-Irénée. The east was defended by the Redoute du Haut-Rhône and Fort de la Vitriolerie on the left bank of the Rhône. The command was situated at Fort Lamothe.[6]

The work required almost 20,000 workers, which were locally sourced in an attempt to avoid insurrection such as the ongoing unrest of the Lyon silk workers (Canuts) over increased capitalism. Work began in 1831 to build seven structures, each structure requiring between 400 and 500 workers. The scope of this project included the construction of Fort de Montessuy and Fort de Caluire to the north; Fort des Brotteaux, Fort Montluc and Fort du Colombier to the east; the Redoute de la Part-Dieu to the west; and Fort Saint-Irénée, to protect the entire area.[6]

In January 1831, an uprising began at a work site in Charpennes, however it was quickly stopped by the army. Other insurrections took place the same year, a series of Canut revolts, which succeeded in rallying soldiers on the side of the Canuts, resulting in the death of captain Viquesnel, aide-de-camp of Fleury, and the temporary withdrawal of the 20,000 soldiers who eventually retook the city in December 1831.[6]

In 1832, three other structures were built to reinforce the defenses to the east: The Redoute de la Tête d'or, Fort La Motte, and the Redoute des Hirondelles. A treaty was signed between the city of Lyon and the War Department, which stipulated that the city had to cede the land necessary for the construction of military buildings to the War Department, while the forts themselves would still belong to the city if the military decided to abandon them. It is thanks to this treaty that the forts of Croix Rousse, Fourvière, Loyasse, Vaise, and Saint-Jean would later be returned to the city.[3]

Construction resumed in 1840. First the Fort de la Vitriolerie in 1840, then Fort de Sainte-Foy-lès-Lyon and the Lunette des Charpennes in 1842, Fort de la Duchère in 1844, the Redoute du Petit Sainte-Foy-lès-Lyon in 1852, and finally the Redoute du haut-Rhône in 1854.[7]

A law was voted in on 10 July 1851,[8] which defined the methods of destruction of these buildings or construction on their land. By 1854, 19 structures including 10 forts had been built around Lyon, creating a nearly 14-kilometre (8.7 mi) fortified perimeter.[6]

Franco-Prussian War

On 19 July 1870, France declared war on Prussia. On 20 August 1870, the Prussians besieged Metz, and Paris on 19 September 1870. It was feared that Lyon would be next. The army in Lyon was commanded by the général de division, Ulrich Ochsenbein at the time.[9]

During the Battle of Sedan on 2 September 1870, France learned that the Germans did not focus on enemy defenses to force cities to surrender. Rather they destroyed homes and population centers using long-range incendiary artillery shells. The forts that were already constructed in France were therefore ineffective in defending against these attacks.[6] The war ended after the signing of the Treaty of Frankfurt on 10 May 1871, and the Ministry of the Armed Forces requested a report on the construction of military works for the defense of Lyon on 4 August 1871. The ministry concluded that the forts constructed before 1870 (Rohault de Fleury) were obsolete because they were too close to the city, and that new rifled cannons could reach a distance of 50 kilometres (31 mi).[10]

A budget of 25,000,000 francs (approximately €110,000,000 as of 2015) was allocated for the defense of the Alps, half of that was used for the defense of Lyon to protect from invasion by the Swiss. The project was awarded by then president Patrice de MacMahon, to the director of Military engineering and Brigadier general Raymond Adolphe Séré de Rivières in 1874. The proposed defenses included the construction of a fort and batteries on Mont Verdun to protect the right bank of the Saône, the forts of Vénissieux, Bron and Cusset to protect the left banks of the Rhône, and a fortification between the Rhône and the Saône at la Pape.[6]

Powder magazines

Although most of the fortified structures had gunpowder magazines to supply the artillery, fortified magazines were set up behind the defense lines. Place de Lyon was divided into four sectors, each with its own dedicated gunpowder magazine. The first, (Fort du Mont Verdun) was created in Fort de la Duchère, the second (Fort de Vancia) at Sathonay, the third (Fort de Feyzin) in an underground magazine at Saint-Fons, and the fourth (fort du Bruissin) in Fort de Sainte-Foy.[11] These magazines were connected by road or rail. The two underground magazines, Saint-Fons built in 1890 and Sathonay in 1894, each had a capacity of 100 t (98 long tons; 110 short tons) of gunpowder. An annex was built near Saint-Fons in 1895 to store picric acid.

Construction of the second belt

Military leaders saw an urgent need to construct four additional forts: The Fort du Mont Verdun in 1874 to the north, the Fort de Bron and Fort de Feyzin in 1875 to the east, and the Fort de Vancia in 1876.[12]

Other projects started in 1878 include the Batterie de la Freta, connected to fort du Mont Verdun; the Batterie de Sathonay and Batterie de Sermenaz, connected to Fort de Vancia; the Fort du Bruissin; the Fort de Corbas; and the Batteries de Parilly and Lessignas.[13]

The construction of Fort du Paillet began in 1883, then Fort de Meyzieu and Fort de Genas the following year.[14] Picric acid began to be used on the battlefield at this time. The explosion caused by this chemical was so powerful that the forts proved to be ineffective, and consequently their construction was temporarily put on hold. The damage caused by this new weapon, along with the rifled-barreled weapons deployed in battle in 1860, proved to be a significant problem.[15][6]

An experiment was conducted in 1886 by military engineers to verify the power of picric acid and its impact on their fortification systems.[16] Fort Malmaison, which had recently been constructed near Paris, was the target of 171 test shells of all calibers containing picric acid. The results showed that the impacts of the new shells left craters 6 meters in diameter, and were capable of breaching the powder magazine to create a huge explosion. An expensive and more effective fortification material, reinforced concrete, was available; however, it was only used on the forts of the Maginot Line and certain strategic parts of the Lyon forts, such as the barracks of Cavalier de Vancia.[17][18]

The decree of 21 January 1887 by General Boulanger, then Minister of the Armies of the French Republic, renamed the military buildings to honor local military victors and victories. Therefore, Fort de Vaise became "Fort Clerc", Fort de Loyasse became "Fort Blandan" after Jean Pierre Hippolyte Blandan, Fort Saint-Jean was renamed "Fort Maupetit", Fort Saint-Irénée became "Fort Dubois-Crancé" after Edmond Louis Alexis Dubois-Crancé, Fort de la Vitriolerie became "Fort Chabert", fort de Villeurbanne became "Fort Montluc" after Blaise de Monluc, and the Barracks of Fort Part-Dieu became the "Barracks of Margaron" after Pierre Margaron.[19]

On 22 July 1887, it also specified several modifications to be made to the forts, including moving the artillery from the forts to the batteries, and using concrete in place of traditional masonry. Fort de Saint-Priest was built with this new material in 1887,[20] followed by Fort de Chapoly in 1891.[21]

First belt

The first belt, called the Rohault de Fleury system, consisted of 22 fortifications commissioned by Rohault de Fleury. They were situated in a radius of about 2.5 km (1.6 mi) around the urban center of Lyon. This belt was constructed between 1830 and 1870.[7]

- Fort de la Duchère (45°47′17″N 4°47′52″E / 45.78814540747424°N 4.797710180282593°E) (destroyed, currently a sports complex)

- Fort de Caluire (45°47′35″N 4°50′12″E / 45.793008080226016°N 4.83673095703125°E) (destroyed, currently a stadium Henri Cochet)

- Fort de Montessuy (45°47′31″N 4°50′51″E / 45.79188596263022°N 4.847545623779297°E)

- Redoute Bel-Air (45°47′19″N 4°50′51″E / 45.78849703034833°N 4.847513437271118°E)

- Fort de Sainte-Foy (45°44′35.01″N 4°48′15.46″E / 45.7430583°N 4.8042944°E)

- Lunette du Petit Sainte-Foy (45°44′54.91″N 4°48′22.28″E / 45.7485861°N 4.8061889°E)

- Fort Saint-Irénée (45°44′57.34″N 4°48′39.71″E / 45.7492611°N 4.8110306°E)

- Lunette du Fossoyeur (45°45′45.95″N 4°48′36.88″E / 45.7627639°N 4.8102444°E)

- Fort de Loyasse (45°45′57.42″N 4°48′33.2″E / 45.7659500°N 4.809222°E)

- Fort de Vaise (45°46′16.18″N 4°48′35.46″E / 45.7711611°N 4.8098500°E)

- Fort Saint-Jean (45°46′14″N 4°48′55″E / 45.77054646821525°N 4.815348386764526°E)

- Bastion Saint-Laurent (45°46′28.19″N 4°50′11.61″E / 45.7744972°N 4.8365583°E)

- Redoute du haut-Rhône (45°46′38″N 4°50′42″E / 45.777199°N 4.84496°E) (destroyed, currently a park entrance)

- Redoute de la Tête d'Or (45°46′29.61″N 4°50′54.25″E / 45.7748917°N 4.8484028°E) (destroyed, currently Boulevard des Belges, Guimet Museum and parc de la Tête d'Or)

- Lunette des Charpennes (45°46′18″N 4°51′26″E / 45.77167°N 4.85722°E) (destroyed, currently lycée du Parc)

- Fort des Brotteaux (45°46′2.54″N 4°51′38.05″E / 45.7673722°N 4.8605694°E) (destroyed, currently Gare des Brotteaux)

- Redoute de la Part-Dieu (45°45′43.6″N 4°51′20.71″E / 45.762111°N 4.8557528°E) (became the barracks of Part-Dieu, then later destroyed, currently Centre commercial de la Part Dieu)

- Fort Montluc (45°45′07″N 4°51′47″E / 45.75195754529761°N 4.862979054450989°E)

- Redoute des Hirondelles (45°44′52.86″N 4°51′37.13″E / 45.7480167°N 4.8603139°E) (destroyed, currently the fr:Manufacture des Tabacs de Lyon)

- Fort Lamothe (45°44′40″N 4°51′07″E / 45.744474569949254°N 4.852019548416138°E)

- Fort du Colombier (45°44′47.52″N 4°50′33.37″E / 45.7465333°N 4.8426028°E) (destroyed, was on the site of place Jean-Macé)

- Fort de la Vitriolerie (45°44′31.25″N 4°49′48.23″E / 45.7420139°N 4.8300639°E)

- Rempart de la Croix-Rousse (45°46′26.36″N 4°49′34.61″E / 45.7739889°N 4.8262806°E) (destroyed in 1865, currently Boulevard de la Croix-Rousse[22])

- Enceinte de Fourvière (45°45′16.18″N 4°49′19.99″E / 45.7544944°N 4.8222194°E)

- Enceinte de Caluire (45°47′30.47″N 4°50′31.83″E / 45.7917972°N 4.8421750°E) (destroyed, currently the streets of Albert-Thomas and Place Professeur-Calmette)

Fort de Grange-Blanche and the Batterie de Pierre Scize[23] were planned but never constructed.

Second belt

The second belt, called the Séré de Rivières system, consisted of twenty-six fortifications surrounding the suburban area of Lyon.[15] They were situated in an 8.5 km (5.3 mi) ring around Lyon. The belt was constructed between 1871 and 1890.

- Mur d'enceinte de Croix-Luizet in Gerland (1884). Currently the location of the Boulevard périphérique de Lyon

- Fort du Mont Verdun (Air force, Mont-Verdun) (45°50′57″N 4°46′46″E / 45.849178°N 4.779497°E)

- Batterie des Carrières (45°50′47″N 4°46′32″E / 45.846353641192806°N 4.775455892086029°E)

- Batterie du Mont-Thou (45°50′28″N 4°47′49″E / 45.84101073418494°N 4.796949774026871°E)

- Batterie de Narcel (45°50′22″N 4°47′11″E / 45.839551365247345°N 4.786470383405685°E)

- Batterie de la Freta (approximation: 45°49′43″N 4°49′25″E / 45.828622°N 4.823664°E)

- Fort de Vancia (45°50′18″N 4°54′25″E / 45.8384498059809°N 4.906854629516602°E)

- Batterie de Sathonay (45°50′12″N 4°52′13″E / 45.836636°N 4.870283°E)

- Magasin de Sathonay (45°49′35″N 4°52′49″E / 45.82632280395762°N 4.8802632093429565°E)

- Batterie de Sermenaz (45°48′44″N 4°55′14″E / 45.812125491557886°N 4.920608997344971°E)

- Redoutes de Neyron (45°49′41″N 4°55′22″E / 45.82816379653716°N 4.922819137573242°E and 45°49′29″N 4°56′02″E / 45.82480697654654°N 4.933805465698242°E)

- Fort de Meyzieu (45°45′20″N 5°00′43″E / 45.755591985246376°N 5.011847019195557°E)

- Fort de Genas (45°43′48″N 5°00′51″E / 45.72999989660979°N 5.014164447784424°E)

- Fort de Bron (45°43′56″N 4°55′16″E / 45.73230651075432°N 4.921102523803711°E)

- Batterie de Lessivas (45°44′44″N 4°54′52″E / 45.74546287431212°N 4.914482831954956°E)

- Batterie de Parilly (45°43′26″N 4°54′02″E / 45.723813506558315°N 4.9004387855529785°E)

- Fort de Saint-Priest (45°41′41″N 4°57′59″E / 45.694669843547246°N 4.96631383895874°E)

- Fort de Corbas (45°40′37″N 4°54′31″E / 45.67701893048473°N 4.908657073974609°E)

- Fort de Feyzin (45°40′19″N 4°52′01″E / 45.67192123992534°N 4.866927266120911°E)

- Fort de Champvillard (45°40′17″N 4°48′43″E / 45.67140394831587°N 4.8118481040000916°E)

- Fort de Montcorin (45°40′41″N 4°48′25″E / 45.67804965706156°N 4.806888699531555°E)

- Fort de Côte-Lorette (45°41′55″N 4°47′02″E / 45.69849909400473°N 4.783947765827179°E)

- Fort du Bruissin (45°43′50″N 4°44′21″E / 45.73050166818355°N 4.7392648458480835°E)

- Fort de Chapoly (45°46′02″N 4°43′41″E / 45.76722359619692°N 4.728026390075684°E)

- Fort du Paillet (45°49′31″N 4°44′48″E / 45.82534527756672°N 4.746544361114502°E)

- Magasin de Saint-Fons (45°42′15″N 4°51′32″E / 45.704299°N 4.858897°E)

- Batterie de Décines (45°46′24.31″N 4°58′5.64″E / 45.7734194°N 4.9682333°E)

The fortifications of d'Azieu, Vaulx-en-Velin, Millery, and Chêne-Rond in Dardilly were planned but never constructed.[24]

See also

References

- ^ Chauvy, Gérard (14 August 2016). "Rhône - Histoire 1/4: Lyon, récit d'une ville fortifée". Le Progrès (in French). Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- ^ Chauvy, Gérard (14 August 2016). "Sous la menace de l'Autriche". Le Progrès (in French). Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- ^ a b Ceinture de forts détachés Rouhault de Fleury (in French). Patrimoine Rhône-Alpes. 2004. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- ^ "Vestiges des anciennes fortifications". Patrimoine Lyon (in French). Retrieved 12 December 2018.

- ^ Les fortifications: La métropole et l'héritage de son passé (PDF) (in French). Lyon: Grand Lyon. 13 September 2005. Retrieved 12 December 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g Pinol, Jean-Luc; Butez, Claire-Charlotte; Emmanuelle, Regagnon. Agrandir Paris (1860-1970): Édification et destruction des enceintes militaires au xixe siècle : le cas de Lyon. pp. 49–63. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- ^ a b Chauvy, Gérard (21 August 2016). "La ligne de défense de Rohault de Fleury". Le Progrès (in French). Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- ^ "Loi n°1851-07-10 du 10 juillet 1851 relative au classement des places de guerre et aux servitudes militaires". Légifrance. 21 December 2004. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- ^ Bonjour, Edgar (1999). Ochsenbein, Ulrich (in German). Neue Deutsche Biographie 19. p. 411. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- ^ "Il y a un siècle, la destruction du rempart protégeant la Ville". Viva Interactif - Toute l'info de Villeurbanne en ligne (in French). 4 June 2015. Retrieved 12 December 2018.

- ^ Vaubourg, Cédric; Vaubourg, Julie (2004). "La place forte de Lyon". Fortiff'Séré : L'association Séré de Rivières (in French). Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- ^ Galichon, Jérôme. "Le Fort de Bron". Lumière sur la passé de Bron (in French). Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- ^ Vaubourg, Cédric; Vaubourg, Julie (2004). "Le fort de Bron". Fortiff'Séré : L'association Séré de Rivières (in French). Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- ^ "Le Fort du Paillet". Dardilly.fr (in French). Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- ^ a b Vaubourg, Cédric; Vaubourg, Julie (2004). "Le système Séré de Rivières". Fortiff'Séré : Les fortifications Séré de Rivières (in French). Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- ^ Salat, Nicole (2005). "Archives du Service des Cuirassements (1877-1927)" (PDF). servicehistorique (in French). Château de Vincennes: Service historique de la Défense: Département de l'armée de Terre. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- ^ Keylor, William (2001). The Twentieth-Century World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 122. ISBN 9780195136814.

- ^ "Le projet "4 Séré", l'Oeuvre de Séré de Rivières expliquée par quatre fortifications lyonnaises". Mémoire et fortifications (in French). 2014. Retrieved 16 December 2018.

- ^ Niepce, Léopold (1897). Lyon militaire: notes et documents pour servir à l'histoire de cette ville. Lyon: Bernoux et Cumin. p. 206.

- ^ Vaubourg, Cédric; Vaubourg, Julie (2004). "Le fort de St-Priest". Fortiff'Séré : L'association Séré de Rivières (in French). Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- ^ Vaubourg, Cédric; Vaubourg, Julie (2004). "Le fort de Chapoly". Fortiff'Séré : L'association Séré de Rivières (in French). Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- ^ "Les fortifications de la Croix-Rousse". Musée d'Histoire Militaire. 2012. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- ^ "Le château Pierre-Scize à Lyon". Musée d'Histoire Militaire. 2012. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- ^ Bonijoly, Roger (15 May 2014). "Les batteries extérieures du camp retranché de Lyon" (PDF). Le Fort de Bron (in French). Association du Fort de Bron. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

Bibliography

- Pelletier, Jean; Delfante, Charles (September 2004). Atlas historique du Grand Lyon (in French). Seyssinet-Pariset: Éditions Xavier Lejeune-Libris. pp. 126–131.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|isbn13=ignored (help) - Dallemagne, François (2006). Les défenses de Lyon: Enceintes et fortifications (in French). Lyon: Éditions Lyonnaises d'Art et d'Histoire.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|isbn13=ignored (help) - Bourrust, Bernard (March 2004). "Le site du fort Saint-Irénée de Lyon: à travers les âges". Bulletin (in French). Lyon: Association Culturelle des Sanctuaires de Saint-Irénée et Saint-Just. ISSN 1266-8303.

- Bougnol, André (March 2002). Le fort de Saint-Priest (in French). Association "La San-Priode".

- Brunet, François; Vincent, Mathilde; Chavanne, André (April 2002). Le fort de Bron: Ah! quelle histoire! (in French). Bron: Association du fort de Bron.

- Delafield, Richard (1860). Report on the art of war in Europe: in 1854, 1855, and 1856 (PDF). Washington: George W. Bowman. OCLC 00891923.

- Frijns, Marco; Malchair, Luc; Moulins, Jean-Jacques; Puelinckx, Jean (2008). Index de la fortification française: 1874–1914 (in French). Autoédition. ISBN 978-2-9600829-0-6.

- Stéphane Autran (October 2011). L'occupation du Fort Lamothe au XIXe siècle: Histoire sociale des militaires (pdf) (in French). Lyon.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Astegiano, Suzanne; Boudon, Brigitte; Bourdin, Jean; Duffournet, Gisèle; Honnay, Roland-Marie; Perraud, Marie-Noëlle; Philippe, Henriette (2008). Sathonay: un village, un camp (in French). Illustrated by Henri Bosplatière, Jean Bourdin, Jacqueline Celebrin, Irène Milleron et Joël Roullet. La Taillanderie. pp. 97–102. ISBN 978-2-87629-356-4.

- Jacquemet, Dominique; Lanneau, Jean-Paul; Douai, S.; Richard, J-P (2010). "Au Bois de la Claire: spécial Fort de Loyasse". Au Bois de la Claire de Mouillard À Valmy : Bulletin du Comité d'Intérêt Local (in French). Lyon: CIL Vaise. ISSN 1281-2684.

- Béghain, Patrice; Benoit, Bruno; Corneloup, Gérard; Thevenon, Bruno (May 2009). Dictionnaire historique de Lyon (in French). Lyon: Stéphane Bachès. pp. 508–511. ISBN 978-2-915266-65-8.

- Gautier, Colonel (1986). La défense de Lyon (in French). Lyon.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Vauban, Association (June 2006). Vauban et ses successeurs dans le lyonnais (in French).