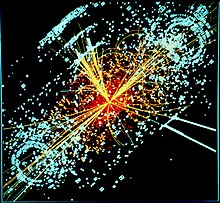

Loop representation in gauge theories and quantum gravity

| Beyond the Standard Model |

|---|

|

| Standard Model |

Attempts have been made to describe gauge theories in terms of extended objects such as Wilson loops and holonomies. The loop representation is a quantum hamiltonian representation of gauge theories in terms of loops. The aim of the loop representation in the context of Yang–Mills theories is to avoid the redundancy introduced by Gauss gauge symmetries allowing to work directly in the space of physical states (Gauss gauge invariant states). The idea is well known in the context of lattice Yang–Mills theory (see lattice gauge theory). Attempts to explore the continuous loop representation was made by Gambini and Trias for canonical Yang–Mills theory, however there were difficulties as they represented singular objects. As we shall see the loop formalism goes far beyond a simple gauge invariant description, in fact it is the natural geometrical framework to treat gauge theories and quantum gravity in terms of their fundamental physical excitations.

The introduction by Ashtekar of a new set of variables (Ashtekar variables) cast general relativity in the same language as gauge theories and allowed one to apply loop techniques as a natural nonperturbative description of Einstein's theory. In canonical quantum gravity the difficulties in using the continuous loop representation are cured by the spatial diffeomorphism invariance of general relativity. The loop representation also provides a natural solution of the spatial diffeomorphism constraint, making a connection between canonical quantum gravity and knot theory. Surprisingly there were a class of loop states that provided exact (if only formal) solutions to Ashtekar's original (ill-defined) Wheeler–DeWitt equation. Hence an infinite set of exact (if only formal) solutions had been identified for all the equations of canonical quantum general gravity in this representation! This generated a lot of interest in the approach and eventually led to loop quantum gravity (LQG).

The loop representation has found application in mathematics. If topological quantum field theories are formulated in terms of loops, the resulting quantities should be what are known as knot invariants. Topological field theories only involve a finite number of degrees of freedom and so are exactly solvable. As a result, they provide concrete computable expressions that are invariants of knots. This was precisely the insight of Edward Witten[1] who noticed that computing loop dependent quantities in Chern–Simons and other three-dimensional topological quantum field theories one could come up with explicit, analytic expressions for knot invariants. For his work in this, in 1990 he was awarded the Fields Medal. He is the first and so far the only physicist to be awarded the Fields Medal, often viewed as the greatest honour in mathematics.

Gauge invariance of Maxwell's theory

The idea of gauge symmetries was introduced in Maxwell's theory. Maxwell's equations are

where is the charge density and the current density. The last two equations can be solved by writing fields in terms of a scalar potential, , and a vector potential, :

.

The potentials uniquely determine the fields, but the fields do not uniquely determine the potentials - we can make the changes:

without affecting the electric and magnetic fields, where is an arbitrary function of space-time . These are called gauge transformations. There is an elegant relativistic notation: the gauge field is

and the above gauge transformations read,

.

The so-called field strength tensor is introduced,

which is easily shown to be invariant under gauge transformations. In components,

.

Maxwell's source-free action is given by:

.

The ability to vary the gauge potential at different points in space and time (by changing ) without changing the physics is called a local invariance. Electromagnetic theory possess the simplest kind of local gauge symmetry called (see unitary group). A theory that displays local gauge invariance is called a gauge theory. In order to formulate other gauge theories we turn the above reasoning inside out. This is the subject of the next section.

The connection and gauges theories

The connection and Maxwell's theory

We know from quantum mechanics that if we replace the wave-function, , describing the electron field by

that it leaves physical predictions unchanged. We consider the imposition of local invariance on the phase of the electron field,

The problem is that derivatives of are not covariant under this transformation:

.

In order to cancel out the second unwanted term, one introduces a new derivative operator that is covariant. To construct , one introduces a new field, the connection :

.

Then

The term is precisely cancelled out by requiring the connection field transforms as

.

We then have that

.

Note that is equivalent to

which looks the same as a gauge transformation of the gauge potential of Maxwell's theory. It is possible to construct an invariant action for the connection field itself. We want an action that only has two derivatives (since actions with higher derivatives are not unitary). Define the quantity:

.

The unique action with only two derivatives is given by:

.

Therefore, one can derive electromagnetic theory from arguments based solely on symmetry.

The connection and Yang-Mills gauge theory

We now generalize the above reasoning to general gauge groups. One begins with the generators of some Lie algebra:

Let there be a fermion field that transforms as

Again the derivatives of are not covariant under this transformation. We introduce a covariant derivative

with connection field given by

We require that transforms as:

- .

We define the field strength operator

- .

As is covariant, this means that the tensor is also covariant:

Note that is only invariant under gauge transformations if is a scalar, that is, only in the case of electromagnetism.

We can now construct an invariant action out of this tensor. Again we want an action that only has two derivatives. The simplest choice is the trace of the commutator:

The unique action with only two derivatives is given by:

This is the action for Yang-mills theory.

The loop representation of the Maxwell theory

We consider a change of representation in the quantum Maxwell gauge theory. The idea is to introduce a basis of states labeled by loops whose inner product with the connection states is given by

The loop functional is the Wilson loop for the abelian case.

The loop representation of Yang–Mills theory

We consider for simplicity (and because later we will see this is the relevant gauge group in LQG) an Yang–Mills theory in four dimensions. The field variable of the continuous theory is an connection (or gauge potential) , where is an index in the Lie algebra of . We can write for this field

where are the generators, that is the Pauli matrices multiplied by . note that unlike with Maxwell's theory, the connections are matrix-valued and don't commute, that is they are non-Abelian gauge theories. We must take this into account when defining the corresponding version of the holonomy for Yang–Mills theory.

We first describe the quantum theory in terms of connection variable.

The connection representation

In the connection representation the configuration variable is and its conjugate momentum is the (densitized) triad . It is most natural to consider wavefunctions . This is known as the connection representation. The canonical variables get promoted to quantum operators:

(analogous to the position representation ) and the triads are functional derivatives,

(analogous to )

The holonomy and Wilson loop

Let us return to the classical Yang–Mills theory. It is possible to encode the gauge invariant information of the theory in terms of `loop-like' variables.

We need the notion of a holonomy. A holonomy is a measure of how much the initial and final values of a spinor or vector differ after parallel transport around a closed loop; it is denoted

Knowledge of the holonomies is equivalent to knowledge of the connection, up to gauge equivalence. Holonomies can also be associated with an edge; under a Gauss Law these transform as

For a closed loop if we take the trace of this, that is, putting and summing we obtain

or

Thus the trace of an holonomy around a closed loop is gauge invariant. It is denoted

and is called a Wilson loop. The explicit form of the holonomy is

where is the curve along which the holonomy is evaluated, and is a parameter along the curve, denotes path ordering meaning factors for smaller values of appear to the left, and are matrices that satisfy the algebra

The Pauli matrices satisfy the above relation. It turns out that there are infinitely many more examples of sets of matrices that satisfy these relations, where each set comprises matrices with , and where none of these can be thought to `decompose' into two or more examples of lower dimension. They are called different irreducible representations of the algebra. The most fundamental representation being the Pauli matrices. The holonomy is labelled by a half integer according to the irreducible representation used.

Giles' Reconstruction theorem of gauge potentials from Wilson loops

An important theorem about Yang–Mills gauge theories is Giles' theorem, according to which if one gives the trace of the holonomy of a connection for all possible loops on a manifold one can, in principle, reconstruct all the gauge invariant information of the connection.[2] That is, Wilson loops constitute a basis of gauge invariant functions of the connection. This key result is the basis for the loop representation for gauge theories and gravity.

The loop transform and the loop representation

The use of Wilson loops explicitly solves the Gauss gauge constraint. As Wilson loops form a basis we can formally expand any Gauss gauge invariant function as,

.

This is called the loop transform. We can see the analogy with going to the momentum representation in quantum mechanics. There one has a basis of states labelled by a number and one expands

and works with the coefficients of the expansion .

The inverse loop transform is defined by

This defines the loop representation. Given an operator in the connection representation,

one should define the corresponding operator on in the loop representation via,

where is defined by the usual inverse loop transform,

A transformation formula giving the action of the operator on in terms of the action of the operator on is then obtained by equating the R.H.S. of with the R.H.S. of with substituted into , namely

or

where by we mean the operator but with the reverse factor ordering (remember from simple quantum mechanics where the product of operators is reversed under conjugation). We evaluate the action of this operator on the Wilson loop as a calculation in the connection representation and rearranging the result as a manipulation purely in terms of loops (one should remember that when considering the action on the Wilson loop one should choose the operator one wishes to transform with the opposite factor ordering to the one chosen for its action on wavefunctions ).

The loop representation of quantum gravity

Ashtekar–Barbero variables of canonical quantum gravity

The introduction of Ashtekar variables cast general relativity in the same language as gauge theories. It was in particular the inability to have good control over the space of solutions to the Gauss' law and spatial diffeomorphism constraints that led Rovelli and Smolin to consider a new representation – the loop representation.[3]

To handle the spatial diffeomorphism constraint we need to go over to the loop representation. The above reasoning gives the physical meaning of the operator . For example, if corresponded to a spatial diffeomorphism, then this can be thought of as keeping the connection field of where it is while performing a spatial diffeomorphism on instead. Therefore, the meaning of is a spatial diffeomorphism on , the argument of .

In the loop representation we can then solve the spatial diffeomorphism constraint by considering functions of loops that are invariant under spatial diffeomorphisms of the loop . That is, we construct what mathematicians call knot invariants. This opened up an unexpected connection between knot theory and quantum gravity.

The loop representation and eigenfunctions of geometric quantum operators

The easiest geometric quantity is the area. Let us choose coordinates so that the surface is characterized by . The area of small parallelogram of the surface is the product of length of each side times where is the angle between the sides. Say one edge is given by the vector and the other by then,

From this we get the area of the surface to be given by

where and is the determinant of the metric induced on . This can be rewritten as

The standard formula for an inverse matrix is

Note the similarity between this and the expression for . But in Ashtekar variables we have . Therefore,

According to the rules of canonical quantization we should promote the triads to quantum operators,

It turns out that the area can be promoted to a well defined quantum operator despite the fact that we are dealing with product of two functional derivatives and worse we have a square-root to contend with as well.[4] Putting , we talk of being in the J-th representation. We note that . This quantity is important in the final formula for the area spectrum. We simply state the result below,

where the sum is over all edges of the Wilson loop that pierce the surface .

The formula for the volume of a region is given by

The quantization of the volume proceeds the same way as with the area. As we take the derivative, and each time we do so we bring down the tangent vector , when the volume operator acts on non-intersecting Wilson loops the result vanishes. Quantum states with non-zero volume must therefore involve intersections. Given that the anti-symmetric summation is taken over in the formula for the volume we would need at least intersections with three non-coplanar lines. Actually it turns out that one needs at least four-valent vertices for the volume operator to be non-vanishing.

Mandelstam identities: su(2) Yang–Mills

We now consider Wilson loops with intersections. We assume the real representation where the gauge group is . Wilson loops are an over complete basis as there are identities relating different Wilson loops. These come about from the fact that Wilson loops are based on matrices (the holonomy) and these matrices satisfy identities, the so-called Mandelstam identities (see Mandelstam variables). Given any two matrices and it is easy to check that,

This implies that given two loops and that intersect, we will have,

where by we mean the loop traversed in the opposite direction and means the loop obtained by going around the loop and then along . See figure below. This is called a Mandelstam identity of the second kind. There is the Mandelstam identity of the first kind . Spin networks are certain linear combinations of intersecting Wilson loops designed to address the over-completeness introduced by the Mandelstam identities.

Spin network states

In fact spin networks constitute a basis for all gauge invariant functions which minimize the degree of over-completeness of the loop basis, and for trivalent intersections eliminate it entirely.

As mentioned above the holonomy tells you how to propagate test spin half particles. A spin network state assigns an amplitude to a set of spin half particles tracing out a path in space, merging and splitting. These are described by spin networks : the edges are labelled by spins together with `intertwiners' at the vertices which are prescription for how to sum over different ways the spins are rerouted. The sum over rerouting are chosen as such to make the form of the intertwiner invariant under Gauss gauge transformations.

Uniqueness of the loop representation in LQG

Theorems establishing the uniqueness of the loop representation as defined by Ashtekar et al. (i.e. a certain concrete realization of a Hilbert space and associated operators reproducing the correct loop algebra – the realization that everybody was using) have been given by two groups (Lewandowski, Okolow, Sahlmann and Thiemann)[5] and (Christian Fleischhack).[6] Before this result was established it was not known whether there could be other examples of Hilbert spaces with operators invoking the same loop algebra, other realizations, not equivalent to the one that had been used so far.

Knot theory and loops in topological field theory

A common method of describing a knot (or link, which are knots of several components entangled with each other) is to consider its projected image onto a plane called a knot diagram. Any given knot (or link) can be drawn in many different ways using a knot diagram. Therefore, a fundamental problem in knot theory is determining when two descriptions represent the same knot. Given a knot diagram, one tries to find a way to assign a knot invariant to it, sometimes a polynomial – called a knot polynomial. Two knot diagrams with different polynomials generated by the same procedure necessarily correspond to different knots. However, if the polynomials are the same, it may not mean that they correspond to the same knot. The better a polynomial is at distinguishing knots the more powerful it is.

In 1984, Jones [7] announced the discovery of a new link invariant, which soon led to a bewildering profusion of generalizations. He had found a new knot polynomial, the Jones polynomial. Specifically, it is an invariant of an oriented knot or link which assigns to each oriented knot or link a polynomial with integer coefficients.

In the late 1980s, Witten coined the term topological quantum field theory for a certain type of physical theory in which the expectation values of observable quantities are invariant under diffeomorphisms.

Witten [8] gave a heuristic derivation of the Jones polynomial and its generalizations from Chern–Simons theory. The basic idea is simply that the vacuum expectation values of Wilson loops in Chern–Simons theory are link invariants because of the diffeomorphism-invariance of the theory. To calculate these expectation values, however, Witten needed to use the relation between Chern–Simons theory and a conformal field theory known as the Wess–Zumino–Witten model (or the WZW model).

References

- ^ Witten, Edward (1989). "Quantum field theory and the Jones polynomial". Communications in Mathematical Physics. 121 (3). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 351–399. doi:10.1007/bf01217730. ISSN 0010-3616.

- ^ Giles, R. (1981-10-15). "Reconstruction of gauge potentials from Wilson loops". Physical Review D. 24 (8). American Physical Society (APS): 2160–2168. doi:10.1103/physrevd.24.2160. ISSN 0556-2821.

- ^ Rovelli, Carlo; Smolin, Lee (1988-09-05). "Knot Theory and Quantum Gravity". Physical Review Letters. 61 (10). American Physical Society (APS): 1155–1158. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.61.1155. ISSN 0031-9007.

- ^ For example see section 8.2 of A First Course in Loop Quantum Gravity, Gambini, R, and Pullin, J. Published by Oxford University Press 2011.

- ^ Lewandowski, Jerzy; Okołów, Andrzej; Sahlmann, Hanno; Thiemann, Thomas (2006-08-22). "Uniqueness of Diffeomorphism Invariant States on Holonomy–Flux Algebras". Communications in Mathematical Physics. 267 (3). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 703–733. arXiv:gr-qc/0504147. doi:10.1007/s00220-006-0100-7. ISSN 0010-3616.

- ^ Fleischhack, Christian (2006-08-11). "Irreducibility of the Weyl Algebra in Loop Quantum Gravity". Physical Review Letters. 97 (6). American Physical Society (APS): 061302. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.97.061302. ISSN 0031-9007.

- ^ V. Jones, A polynomial invariant for knots via von Neumann algebras, reprinted in ``New Developments in the Theory of Knots, ed. T. Kohno, World Scientific, Singapore, 1989.

- ^ Witten, E. (1989). "Quantum field theory and the Jones polynomial". Commutations in Mathematical Physics. 121: 351–399. MR 0990772.

![{\displaystyle A_{\mu }'(x)=A_{\mu }(x)+{i \over g}[\partial _{\mu }\Omega (x)]\Omega ^{-1}(x)\quad Eq1.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c7d77f98c226793b201623c24f07d29f7ea36aab)

![{\displaystyle F_{\mu \nu }={-i \over g}[{\mathcal {D}}_{\mu },{\mathcal {D}}_{\mu }]={-i \over g}[\partial _{\mu }+igA_{\mu }(x),\partial _{\nu }+igA_{\nu }(x)]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ef1f7018b8df8ffdd24073ca8206d0700164f34d)

![{\displaystyle ={-i \over g}{\Big (}[\partial _{\mu },\partial _{\nu }]+ig(\partial _{\mu }A_{\nu }-\partial _{\nu }A_{\mu })-g^{2}[A_{\mu },A_{\nu }]{\Big )}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d698093ba1b6efeadb899bdbf52cbdeaf8b26f61)

![{\displaystyle [T_{i},T_{j}]=if^{ijk}T^{k}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/068008264991fd736cb56077eacd7a7f19fb94ed)

![{\displaystyle \mathbf {F} _{\mu \nu }=-{i \over g}[\mathbf {\mathcal {D}} _{\mu },\mathbf {\mathcal {D}} _{\nu }]=\partial _{\mu }\mathbf {A} _{\nu }-\partial _{\nu }\mathbf {A} _{\mu }+ig[\mathbf {A} _{\mu },\mathbf {A} _{\nu }]=(\partial _{\mu }A_{\nu }^{i}-\partial _{\nu }A_{\mu }^{i}+gf^{ijk}A_{\mu }^{j}A_{\nu }^{k})T^{i}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2dfba2696b6ff6e6748f631f92044256d4f6392b)

![{\displaystyle \langle A\mid \gamma \rangle =W(\gamma )=\exp \left[ie\int _{\gamma }dy^{\alpha }A_{\alpha }(y)\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c6dc29826d2a0facaf566d6bc205bf986f0ced82)

![{\displaystyle {\hat {A}}_{a}^{i}\Psi [A]=A_{a}^{i}\Psi [A]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/6bb9ad9bb9433411a941f6927608baf7493d0d93)

![{\displaystyle {\hat {\tilde {E}}}_{a}^{i}\Psi [A]=-i{\delta \Psi [A] \over \delta A_{a}^{i}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2804003fd7f11a4068248ddc3d07f1ee55322a5c)

![{\displaystyle h_{\gamma }[A]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/5973c57773fff6566ac2ec6b949f95f54abc1839)

_{\gamma \sigma }=\delta _{\sigma \gamma }(h_{e})_{\gamma \sigma }=(h_{e})_{\gamma \gamma }}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/33f90738e5a7f7ab8a65b5628ff81387ab6c33ed)

![{\displaystyle W_{\gamma }[A]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9c819a5d3e9f069d989a2ad345c11829e02f1c75)

![{\displaystyle h_{\gamma }[A]={\mathcal {P}}\exp {\Big \{}-\int _{\gamma _{0}}^{\gamma _{1}}\,ds{\dot {\gamma }}^{a}A_{a}^{i}(\gamma (s))T_{i}{\Big \}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/74d73b642434e75545941d1c4b80a2105522a18a)

![{\displaystyle [T^{i},T^{j}]=2i\epsilon ^{ijk}T^{k}.\,}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/dabb626dc3b33e0ab4ee86377796cfbe9ddfaa83)

![{\displaystyle \Psi [A]=\sum _{\gamma }\Psi [\gamma ]W_{\gamma }[A]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/da9dddd3b8e7e5bd0000e8b10fdd354f8b857e74)

![{\displaystyle \psi [x]=\int dk\psi (k)\exp(ikx).}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d85a46131c1ad49af54e081e983a0ed8d63f9e59)

![{\displaystyle \Psi [\gamma ]=\int [dA]\Psi [A]W_{\gamma }[A].}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/cc2e9d9ed1967f1603f6e0846288389f32024bc6)

![{\displaystyle \Phi [A]={\hat {O}}\Psi [A],\qquad {\text{Eq 1}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a2e21f957f68164ddbde002a24298e07925042af)

![{\displaystyle \Psi [\gamma ]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/6f8d7cdd9ae00dddc142ba1e03d35be57173be57)

![{\displaystyle \Phi [\gamma ]={\hat {O}}'\Psi [\gamma ],\qquad {\text{Eq 2}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f31080d853dc46a7f4e3d8baf3b0a6d6984356a6)

![{\displaystyle \Phi [\gamma ]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/bd437ac38e2d2510ea77d74b23159f8a837c7d8c)

![{\displaystyle \Phi [\gamma ]=\int [dA]\Phi [A]W_{\gamma }[A].\qquad {\text{Eq 3}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/adc9c59e0c30698b130841c491bcd6678b06c9f6)

![{\displaystyle \Psi [A]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/67ff914baeb5bd928ed9ccd89572a317f07999d3)

![{\displaystyle {\hat {O}}'\Psi [\gamma ]=\int [dA]W_{\gamma }[A]{\hat {O}}\Psi [A],}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/6a543ce03ec8af24844b0d192255b2d2796a4f3b)

![{\displaystyle {\hat {O}}'\Psi [\gamma ]=\int [dA]({\hat {O}}^{\dagger }W_{\gamma }[A])\Psi [A],}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c67103fe0425024a17fba51c2bef15c240bc9b1a)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}A&=\|{\vec {u}}\|\|{\vec {v}}\|\sin \theta ={\sqrt {\|{\vec {u}}\|^{2}\|{\vec {v}}\|^{2}(1-\cos ^{2}\theta )}}\\[6pt]&={\sqrt {\|{\vec {u}}\|^{2}\|{\vec {v}}\|^{2}-({\vec {u}}\cdot {\vec {v}})^{2}}}\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8e843cc20b2ee61001b35186492f36eb02eefcdd)

![{\displaystyle {\hat {A}}_{\Sigma }W_{\gamma }[A]=8\pi \ell _{Planck}^{2}\beta \sum _{I}{\sqrt {j_{I}(j_{I}+1)}}W_{\gamma }[A]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/edd0c107875410a987571fc3c874d40eab3616d8)

![{\displaystyle W_{\gamma }[A]W_{\eta }[A]=W_{\gamma \circ \eta }[A]+W_{\gamma \circ \eta ^{-1}}[A]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/aec1b1ef8986563650edd01ae423d6d5ed3d9d02)