Khalili Collection of Aramaic Documents

| The Khalili Collection of Aramaic Documents | |

|---|---|

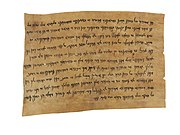

A long list of supplies disbursed, dated the seventh year of Alexander the Great's reign, 324BC | |

| Curators | Nasser D. Khalili (founder) Dror Elkvity (Curator and Chief Co-ordinator)[1] |

| Size (no. of items) | 48[2] |

| Website | website |

The Khalili Collection of Aramaic Documents is a private collection of letters and documents from the Bactria region in present-day Afghanistan, assembled by the British-Iranian scholar, collector and philanthropist Nasser D. Khalili. It is one of the Khalili Collections: eight collections assembled, conserved, published and exhibited by Khalili, each of which is considered among the most important in its field.[3][4] The documents, written in Official Aramaic, likely originated from the historical city of Balkh and all are dated between 353 BC to 324 BC during the reigns of Artaxerxes III and Artaxerxes IV. The newest of the documents was written during Alexander the Great's early reign in the region, using in Aramaic the original Greek form Alexandros (spelled Lksndrs) instead of the Eastern variant Iskandar (spelled Lksndr). The collection is significant for the linguistic study of the Official Aramaic language and of daily life in the Achaemenid empire.

The Achaemenid empire

The empire, established in 559 BC by Cyrus the Great, covered the whole Middle East from India to Africa.[5] It had an effective postal system and a book-keeping system based on a small number of languages, mainly Official Aramaic.[6] Thus official records such as the Khalili documents were in Aramaic although that was not the spoken language of ordinary life in Bactria.[7] Local rulers known as satraps implemented royal decrees in their provinces.[5] There are references to administrative details of the Achaemenid court in the Book of Esther, which therefore must have been written by someone living close to the court.[7] The Khalili documents give an insight into the administration of this empire and its eventual fall to Alexander the Great in 329 BC, dealing with topics such as city fortifications, military leave, and food delivery.[8][9][10]

Khalili Collections

The collection is one of eight assembled by Nasser D. Khalili, each of which is considered among the most important in its field.[11][12] These include the world's largest private collection of Islamic art[13][14] and a collection of Meiji-era Japanese art comparable only to the collection of the Japanese imperial family in terms of size and quality.[15]

Khalili has written that he was motivated to collect Aramaic documents from the Achaemenid period because, as an Iranian Jew, he felt a personal connection to the topic. A queen in the Achaemenid empire, Esther, saved the Jewish people by dissuading her husband Ahasuerus from killing them.[16] He described as unforgettable his experience, as a child in Iran, of hearing Aramaic, the language spoken by Moses and by Jesus.[16]

Documents in the collection

From 1993 to 2002, over a hundred Bactrian documents emerged, in the bazaar of Peshawar and other sources. They included economic documents, legal documents, Buddhist texts, and letters on leather, cloth or wood. Some were found in perfect condition, still sealed.[17] The largest collection of these was acquired by Nasser D. Khalili.[18] This collection comprises 48 historically significant documents in Official Aramaic, consisting mainly of letters and accounts related to the court of the satrap of Bactria, whose capital city was Balkh. Similarities between these documents suggest that they are almost all from one archive in or near Balkh.[19] Thirty of these are documents written on leather; the remaining eighteen are sticks of wood used to record debts.[20] They are dated between 353 BC to 324 BC during the reigns of Artaxerxes III and, to a lesser extent, Artaxerxes IV.[21]

Together these letters and accounts make up the first discovered correspondence of the administration of Bactria and Sogdiana.[22] They contain many grammatical errors of Aramaic, reflecting that the scribes were not everyday users of the language but would have been trained in it for its official use.[23] The Khalili collection is one of only two sets of Achaemenid documents on leather; the other is the Arshama documents written in Babylonia and now in the collection of the Bodleian Library.[16][22]

Documents on leather

The 30 documents consist of:[24]

- Eighteen letters, mainly from the middle of the 4th century BC but one from the early 5th century.

- Eight of these letters are addressed to a local governor named Bagavant, and seem to come from a superior, thought to be the satrap Akhvamazda.[25] These are likely to be draft copies of letters that were later copied out in a neater hand, the draft copies remaining in the sender's archive.[26] The letters were dictated in Old Persian and written in Aramaic by professional scribes.[27] The letters include orders, in one case to build fortifications around the frontier town of Nikhshapaya (thought to be at the location of modern Qarshi).[28] The content of the letters illuminates the relationship between the two officials, with the satrap chiding Bagavant for disobedience and reporting complaints received.[29] Other letters are more friendly, and seem to be addressed to officials of a similar rank to the satrap.[30] The letters include names of deities who are not mentioned in any other known sources.[31]

- Six lists of supplies.

- Among these is the latest dated document in the collection, dated to year 7 of the reign of Alexander the Great, naming him as "Alexandros" (Lksndrs).[32][33] This is the earliest surviving use in Aramaic of the original (Greek) form of Alexander's name instead of the Eastern variant "Iskandar" (Lksndr).[33] Another list describes the provisions for troops led by Bessus, who took over as king after killing Darius III but whose reign lasted less than a year.[34] The presence of these lists is further evidence that these documents came from the official archive of a satrap.[32]

- A dispatch document, acquired by the collection in its original sealed form, recording a transfer of 40 sheep.[35]

- A one-line text that may have been a label[36]

- Two lists of names, whose purpose is unknown[37]

- Two notes on a debt and acknowledging receipt of goods[38]

Tallies

The 18 wooden sticks are tallies, usually dated, describing quantities of goods.[39] The types of goods are not stated, suggesting that the numbers refer to a standard traded commodity.[40] The dates are written as years of the reign of Darius III.[40] These tallies likely come from the practice of cutting a stick in half so that the supplier and receiver of a good each have a matching record of the transaction.[40] The numerical quantity was not written on the stick; instead, the two halves would be held together and notched with a pattern that expressed the quantity.[41]

-

Small document, perhaps a label

-

Letter from Akhvamazda to Bagavant

-

Letter from Bakhtrifarnah to Chithrachardata

-

Tally stick

References

![]() This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC-BY-SA 3.0. Text taken from The Khalili Collections, Khalili Foundation.

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC-BY-SA 3.0. Text taken from The Khalili Collections, Khalili Foundation.

Notes

- ^ "Aramaic Documents". Khalili Collections. Retrieved 2020-06-30.

- ^ "The Eight Collections". nasserdkhalili.com. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- ^ "The Khalili Collections major contributor to "Longing for Mecca" exhibition at the Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam". www.unesco.org. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. 16 April 2019. Retrieved 2020-06-25.

- ^ Lawson-Tancred, Jo (2019-10-11). "Around the world in 35,000 objects – and a handful of clicks". Apollo Magazine. Retrieved 2020-10-02.

- ^ Reymond, Eric D. (July–September 2016). "Aramaic Documents from Ancient Bactria (Fourth Century B.C.E.) from the Khalili Collections". The Journal of the American Oriental Society. 136 (3). ISSN 0003-0279 – via Questia.

- ^ "Aramaic Documents". Khalili Collections. Retrieved 2020-06-30.

- ^ "The Khalili Collections major contributor to "Longing for Mecca" exhibition at the Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization". www.unesco.org. Retrieved 2020-10-02.

- ^ Lawson-Tancred, Jo (2019-10-11). "Around the world in 35,000 objects – and a handful of clicks". Apollo Magazine. Retrieved 2020-10-02.

- ^ Gayford, Martin (16 April 2004). "Healing the world with art". The Independent. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- ^ Moore, Susan (12 May 2012). "A leap of faith". Financial Times. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- ^ Gagarina, Elena (2017). "Foreword". In Amelekhina, Svetlana; Elkvity, Dror; Panfilov, Fedor (eds.). Beyond Imagination: Treasures of Imperial Japan from the Khalili collection, 19th to early 20th centuries. Moscow. p. 7. ISBN 978-5-88678-308-7. OCLC 1014032691.

Comparable, as acknowledged by many scholars and museum directors, in terms of quality and size only to the collection of the Japanese imperial family, this celebrated collection comprises outstanding art works created during the "Great Change" when, after more than two hundred years of isolation, Japan began promoting itself internationally as a country of rich cultural traditions.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c Khalili, Nasser D., "Foreword" in Naveh & Shaked 2012, p. ix

- ^ Sims-Williams, Nicholas (March 2002). "New Documents in Ancient Bactrian Reveal Afghanistan's Past" (PDF). IIAS Newsletter (27). International Institute for Asian Studies: 12–13.

- ^ Gholami, Saloumeh (2013). "Review of Bactrian Documents from Northern Afghanistan. III: Plates. Studies in the Khalili Collection, Vol. 3. CIIr. Pt. 2, Inscriptions of the Seleucid and Parthian Periods and of Eastern Iran and Central Asia. Vol. 4, Bactrian". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 23 (1): 136–138. ISSN 1356-1863.

- ^ a b "Aramaic Documents | A Long List of Supplies..." Khalili Collections. 2016. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

Sources

- Naveh, Joseph; Shaked, Shaul (2012). Aramaic Documents from Ancient Bactria. Khalili Family Trust. ISBN 9781874780748.