Air gun

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (September 2014) |

An air gun (often called pellet gun or BB gun depending on the projectile) is any variety of pneumatic weapon that propels projectiles by means of compressed air or other gas, in contrast to firearms, which use a propellant charge. Both the rifle and pistol forms (air rifle and air pistol) typically propel metallic projectiles, either pellets, or BBs. Certain types of air guns, usually rifles, may also propel arrows or darts with feathers.

History

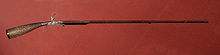

Air guns represent the oldest pneumatic technology. The oldest existing mechanical air gun, a bellows air gun dating back to about 1580, is in the Livrustkammaren Museum in Stockholm. This is the time most historians recognize as the beginning of the modern air gun.

In the 17th century, air guns, in calibers .30–.51, were used to hunt big game deer and wild boar. These air rifles were charged using a pump to fill an air reservoir and gave velocities from 650 to-[convert: unknown unit]. They were also used in warfare, the most recognized example being the Girandoni Military Repeating Air Rifle.

At that time, they had compelling advantages over the primitive firearms of the day. For example, air guns could be discharged in wet weather and rain (unlike matchlock muskets), and repeatedly discharged faster than muzzle-loading guns.[1] Moreover, they were quieter than a firearm of similar caliber, had no muzzle flash, and were smokeless. Thus, they did not disclose the shooter's position or obscure the shooter's view, unlike the black powder muskets of the 18th and 19th centuries.

In the hands of skilled soldiers, they gave the military a distinct advantage. France, Austria and other nations had special sniper detachments using air rifles. The Austrian 1770 model was named Windbüchse (literally "wind rifle" in German). The gun was developed in 1768 or 1769[2] by the Tyrolean watchmaker, mechanic and gunsmith Bartholomäus Girandoni (1744–1799) and is sometimes referred to as the Girandoni Air Rifle or Girandoni air gun in literature (the name is also spelled "Girandony," "Giradoni"[3] or "Girardoni".[4]) The Windbüchse was about 4 ft (1.2 m) long and weighed 10 pounds (4.5 kg), about the same size and mass as a conventional musket. The air reservoir was a removable, club-shaped, butt. The Windbüchse carried twenty-two .51 caliber (13 mm) lead balls in a tubular magazine. A skilled shooter could fire off one magazine in about thirty seconds. A shot from this air gun could penetrate an inch thick wooden board at a hundred paces, an effect roughly equal to that of a modern 9×19mm or .45 ACP caliber pistol.

Circa 1820, the Japanese inventor Kunitomo Ikkansai developed various manufacturing methods for guns, and also created an air gun based on the study of Western knowledge ("rangaku") acquired from the Dutch in Dejima.

The celebrated Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804) carried a reservoir air gun. It held 22 .46 caliber round balls in a tubular magazine mounted on the side of the barrel. The butt served as the air reservoir and had a working pressure of 800 psi (5,500 kPa). The rifle was said to be capable of 22 aimed shots per minute and had a rifled bore of 0.452 in (11.5 mm) and a groove diameter 0.462 in (11.7 mm).

One of the first commercially successful and mass-produced air guns was manufactured by the W.F. Markham Co. Their first model air gun was called the Challenger and marketed in 1888. Their next model was the Chicago followed by the King. The Chicago model was sold by Sears, Roebuck for 73 cents in its catalog. In 1928 the name of the company was changed to King Mfg. Co. and remained so until the company was purchased by the Daisy air gun company.[5]

During the 1890s, air rifles were used in Birmingham, England, for competitive target shooting. Matches were held in public houses, which sponsored shooting teams. Prizes, such as a leg of mutton for the winning team, were paid for by the losing team. The sport became so popular that in 1899, the National Smallbore Rifle Association was created. During this time over 4,000 air rifle clubs and associations existed across Great Britain, many of them in Birmingham. During this time, the air gun was associated with poaching because it could deliver a shot without a significant report.

Use

Air guns are used for hunting, pest control, recreational shooting (commonly known as plinking), and competitive sports, such as the Olympic 10 m Air Rifle and 10 m Air Pistol events. Field Target (FT) is a competitive form of target shooting in which the targets are knock-down metal silhouettes of animals, with a 'kill zone' cut out of the steel plate. Hunter Field Target (HFT) is a variation, using identical equipment, but with differing rules. The distances FT and HFT competitions are shot at range between 7.3 and 41.1 metres (24 and 135 ft) for HFT & 7.3 and 50.29 metres (24.0 and 165.0 ft)for FT, with varying sizes of 'reducers' being used to increase or decrease the size of the kill zone. In the UK, competition power limits are set at the legal maximum for an unlicensed air rifle, i.e. 12 ft⋅lbf (16 J).

Air gun power sources

The different methods of powering an air gun can be broadly divided into 3 groups: spring-piston, pneumatic, and CO2. These methods are used in both air rifles and air pistols.[6]

Spring-piston

Spring-piston air guns are able to achieve muzzle velocities near or greater than the speed of sound from a single stroke of a cocking lever or the barrel itself. The effort required for the cocking stroke is usually related to the power of the gun, with higher muzzle velocities requiring greater effort.

Spring-piston guns operate by means of a coiled steel spring-loaded piston contained within a compression chamber, and separate from the barrel. Cocking the gun causes the piston assembly to compress the spring until the rear of the piston engages the sear. The act of pulling the trigger releases the sear and allows the spring to decompress, pushing the piston forward, thereby compressing the air in the chamber directly behind the pellet. Once the air pressure has risen enough to overcome any static friction and/or barrel restriction holding the pellet, the pellet moves forward, propelled by an expanding column of air. All this takes place in a fraction of a second, during which the air undergoes adiabatic heating to several hundred degrees and then cools as the air expands.

Spring-piston guns have a practical upper limit of 1250 ft/s (380 m/s) for .177 cal (4.5 mm) pellets. Higher velocities cause unstable pellet flight and loss of accuracy. This is due to the extreme buffeting caused when the pellet reaches and passes transonic speed, then slows back down and goes through it again. This is more than enough to destabilize it. Shortly after leaving the barrel, the supersonic pellet falls back below the speed of sound and the shock wave overtakes the pellet, causing its flight to be disrupted. Drag increases rapidly as pellets are pushed past the speed of sound, so it is generally better to increase pellet weight to keep velocities subsonic in high-powered guns. Sonic crack from the pellet as it moves with supersonic speed also makes the shot louder sometimes making it possible to be mistaken for firearm discharge. Many shooters have found that velocities in the 800–900 ft/s (240–270 m/s) range offer an ideal balance between power and pellet stability.

Most spring piston guns are single-shot breech-loaders by nature, but multiple-shot guns have become more common in recent years. Spring guns are typically cocked by a mechanism requiring the gun to be hinged at the midpoint (called a break barrel), with the barrel serving as a cocking lever. Other systems that are used include side levers, under-barrel levers, and motorized cocking, powered by a rechargeable battery.

Spring piston guns, especially high-powered ones, recoil as a result of the forward motion of the piston. Although the recoil is less than that of some cartridge firearms, it can make the gun difficult to shoot accurately as the recoil forces are in effect whilst the pellet is still traveling down the barrel. Spring gun recoil has a sharp forward movement too, caused by the piston hitting the forward end of the chamber when the spring has fully expanded. These two reactions are known to damage scopes not rated for spring gun use.

Spring guns can also suffer from spring vibrations that reduce accuracy. These vibrations can be controlled by adding features like close-fitting spring guides or by aftermarket tuning done by "air-gunsmiths" who specialize in air gun modifications. A common modification is the addition of viscous silicone grease to the spring, which both lubricates it and dampens vibration.

The better quality spring air guns can have very long service lives, being simple to maintain and repair. Because they deliver the same energy on each shot, their trajectory is consistent. Most Olympic air gun matches through the 1970s and into the 1980s were shot with spring-piston guns, often of the opposing-piston recoil-eliminating type. Beginning in the 1980s, guns powered by compressed, liquefied carbon dioxide began to dominate competition. Today, the guns used at the highest levels of competition are powered by compressed air.

Gas Spring

Some makes of air rifle incorporate a gas spring instead of a mechanical spring. Pressurized air or nitrogen is held in a chamber built into the piston, and this air is further pressurized when the gun is cocked. It is, in effect, a gas spring commonly referred to as a "gas ram" or "gas strut". Gas spring units require higher precision to build, since they require a low friction sliding seal that can withstand the high pressures when cocked. The advantages of the gas spring include the facility to keep the rifle cocked and ready to fire for long periods of time without long-term spring fatigue, lower recoil and faster "lock time" (the time between pulling the trigger and the pellet being discharged). The improvement in lock time results in better accuracy.

Pneumatic

Pneumatic air guns utilize compressed air as the source of energy to propel the projectile. Single-stroke and multi-stroke guns utilize an on-board pump to pressurize the air in a reservoir. Pre-charged pneumatic guns' reservoirs are filled using either a high-pressure hand pump or by decanting air from a diving cylinder. This design, having no significant movement of heavy mechanical parts during the firing cycle, produces lower recoil.

Multi-stroke

Multi-stroke pneumatic air guns require the pumping of an on-board lever to store compressed air within the air gun. Variable power can be achieved through this process, as the user can adapt the power level for long, or short-range shooting.

Single-stroke

A single motion of the cocking lever is all that is required to compress the air. The single-pump system is usually found in target rifles and pistols, where the higher muzzle energy of a multi-stroke pumping system is not required. Single-stroke pneumatic rifles dominated the national and international ISSF 10 metre air rifle shooting events from the 1970s up to the 1990s.

Pre-charged pneumatic (PCP)

Pre-charged pneumatic (PCP) air guns are usually filled by decanting from an air reservoir, such as a diving cylinder or by charging directly with a hand pump. Because of the need for cylinders or charging systems, PCP guns have higher initial costs but much lower operating costs when compared to CO2 guns. PCP guns have very low recoil and can fire as many as 500 shots per charge. The ready supply of air has allowed the development of semi and fully automatic[7][8] air guns. PCP guns are very popular in the UK and Europe because of their accuracy and ease of use. They are widely utilized in ISSF 10 metre air pistol and rifle shooting events, the sport of Field Target shooting,[9] and are usually fitted with telescopic sights.

Early hand pump designs encountered problems of fatigue (both human and mechanical), temperature warping, and condensation—none of which are beneficial to accurate shooting or air gun longevity. Modern hand pumps have built-in air filtration systems and have overcome many of these problems. Using scuba-quality air decanted from a scuba cylinder provides consistently clean, dry, high-pressure air.

Unregulated action

During the typical PCP's discharge cycle, the hammer of the rifle is released by the sear to strike the bash valve. The hammer may move rearwards or forwards, unlike firearms where the hammer almost always moves forward. The valve is held closed by a spring and the pressure of the air in the reservoir. The pressure of the spring is constant, and the pressure of the air decreases with each successive shot. As a result, when the reservoir pressure is at its peak, the valve opens less fully and closes faster than when the reservoir pressure is lower, resulting in a similar total volume of air flowing past the valve with each shot. This results in a degree of self-regulation that gives a greater consistency of velocity from shot to shot. A well-designed PCP will display good shot to shot consistency as the air reservoir is depleted.

Regulated action

Other PCP rifles and pistols are regulated, i.e. the firing valve operates within a secondary chamber separated from the main air reservoir by the regulator body. The regulator maintains the pressure within this secondary chamber at a set pressure (lower than the main reservoir's) until the main reservoir's pressure drops to the point where it can no longer do so. As a result, shot to shot consistency is maintained for longer than in an unregulated rifle.

CO2

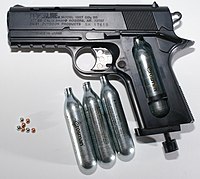

Most CO2 guns use a disposable cylinder, a powerlet, that is often purchased with 12 grams of pressurized carbon dioxide, although some, usually more expensive models, use larger refillable CO2 reservoirs like those typically used with paintball markers.

CO2 guns, like compressed air guns, offer power for repeated shots in a compact package without the need for complex cocking or filling mechanisms. The ability to store power for repeated shots also means that repeating arms are possible. There are many replica revolvers and semi-automatic pistols on the market that use CO2 power. These guns are popular for training, as the guns and ammunition are inexpensive, safe to use, and no specialized facilities are needed for safety. In addition, they can be purchased and owned in areas where firearms possession is either strictly controlled, or banned outright. Most CO2 powered guns are relatively inexpensive, and there are a few precision target guns available that use CO2.

Ammunition

Pellet

The most popular ammunition used in rifled air guns is the lead diabolo pellet. This waisted projectile is hollowed at the base and available in a variety of head styles. The diabolo pellet is designed to be drag stabilized, though is not as stable as some other shapes in the transonic region (272–408 m/s ~ 893–1340 ft/s). Pellets are also manufactured from tin, or a combination of materials such as steel-tipped plastic.

Most air guns are .177 (4.5 mm) or .22 (5.5 mm / 5.6 mm) caliber, and are designed for target practice, small game hunting and field target shooting. Though less common, .20 and .25 caliber (5.0 mm and 6.4 mm) guns also exist.

BB

The BB was once the most common air gun ammunition in the USA. A BB is a small ball, typically made of steel with a copper or zinc plating, of 4.5 mm/.177" diameter. Lead "Round Balls" are manufactured in numerous calibers too; these are often 4.5 mm/.177" diameter and designed for use in .177 caliber rifled guns normally used for shooting pellets. Steel BBs can be acceptably accurate at short distances when fired from properly designed BB guns with smoothbore barrels. Lead number 3 buckshot pellets can be used in .25" caliber airguns as if they were large BBs.

Due to the hardness of the steel, they can not "take" to rifled barrels, which is why they are undersized (4.4 against 4.5 mm) to allow them to be used in .177" rifled barrels, which when used in this configuration can in effect be considered smoothbore, but with a poorer gas-seal. Were they 4.5 mm diameter, they would jam in the bore. Therefore, BB's lack the spin stabilization required for long-range accuracy, and usage in any but the cheapest rifled guns is discouraged.

Typically BBs are used for indoor practice, casual outdoor plinking, training children, or for air gun enthusiasts who like to practice, but cannot afford high-powered air gun systems that use pellets. Some shotgunners use sightless BB rifles to train in instinctive shooting. Similar guns were also used briefly by the United States Army in a Vietnam-era instinctive shooting program called "Quick Kill".[10]

Darts and arrows

In the 18th and 19th centuries air gun darts were very popular, largely due to being able to be reused. Although less popular now, several different types of darts are made to be used in air guns, however it is not recommended that darts be used in air guns with rifled bores, or in spring powered air guns .[11]

Calibers

The most common air gun calibers are

- .177 (4.5 mm): the most common caliber. Mandated by the ISSF for use in international target shooting competition at 10m, up to Olympic level in both rifle and pistol events. It has also been adopted by most National Governing Bodies for domestic use in similar target shooting events. It has the flattest trajectory of all the calibers for a given energy level, making accuracy simpler. At suitable energy levels it can be used effectively for hunting.

- .22 (5.5 mm & 5.6 mm): for hunting and general use. In recent years air rifles and pistols in .22" (and some other calibers) have been allowed for use in both domestic and international target shooting in events not controlled by the ISSF. Most notably in FT/HFT and Smallbore Benchrest competitions. These events often allow the use of any caliber air gun, up to a maximum which is often .22", rather than a fixed caliber.

Other less common traditional calibers include:

- .20 (5 mm): initially proprietary to the Sheridan multi-pump pneumatic air rifle, later more widely used.

- .25 (6.35 mm): the largest commonly available caliber for most of the 20th century.

Larger caliber air rifles suitable for hunting large animals are offered by major manufacturers. These are usually PCP guns. The major calibers available are:

- .357

- .45 (11.43 mm)

- .50 (12.7 mm)

- .58 (14.5 mm)

Custom air guns are available in even larger calibers such as 20 mm (0.79") or .87 (22.1 mm).

Legality

While in some countries air guns are not subject to any specific regulation, in most there are laws, which differ widely. Each jurisdiction has its own definition of an air gun; and regulations may vary for weapons of different bore, muzzle energy or velocity, or material of ammunition, with guns designed to fire metal pellets often more tightly controlled than airsoft weapons. There may be minimum ages for possession, and sales of both air guns and ammunition may be restricted. Some areas require permits and background checks similar to those required for firearms proper.

Safety and misuse

While historical air guns have been made specifically for warfare, modern air guns can also be deadly. In medical literature, modern air guns have been noted as the cause of death.[12][13][14] This has been the case for guns of caliber .177 and .22 that are within the legal muzzle velocity of air guns in the United Kingdom.[15]

See also

References

- ^ Philip, Schreier (October 2006). "The Airgun of Meriwether Lewis". American Rifleman. Retrieved 23 December 2013.

- ^ Arne Hoff, Airguns and Other Pneumatic Arms, Arms & Armour Series, London, 1972

- ^ L.Wesley, Air Guns and Air Pistols, London 1955

- ^ H.L.Blackmore, Hunting Weapons, London 1971

- ^ Laidlaw, Angus (January 2014). "Chicago Air Rifle Markham's Patent". American Rifleman. 162 (1): 48.

- ^ Ben Saltzman. "The Three Basic Types of Airguns". American Airguns. Archived from the original on 15 October 2007. Retrieved 2007-09-14.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Air Ordnance Full Auto Pellet Gun". Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- ^ http://appft1.uspto.gov/netacgi/nph-Parser?Sect1=PTO1&Sect2=HITOFF&d=PG01&p=1&u=/netahtml/PTO/srchnum.html&r=1&f=G&l=50&s1=20110186026.PGNR. Patent for Air Ordnance Full Auto Pellet Gun

- ^ "American Airgun Field Target Association". Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- ^ Time magazine, Friday, July 14, 1967

- ^ "Airgun projectiles". Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- ^ ""Air gun--a deadly toy?: A case report."".

- ^ "Fatal nonpowder firearm wounds: case report and review of the literature".

- ^ "Air weapon injuries: a serious and persistent problem".

- ^ "Air Weapon Fatalities" (PDF).