Al-Maghtas

| Al-Maghtas | |

|---|---|

| Native name المغطس (Arabic) | |

Excavation of baptism site | |

| Location | Jordan River, Jordan |

| Website | baptismsite.com |

| Official name | Baptism Site "Bethany Beyond the Jordan" (Al-Maghtas) |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | III, VI |

| Designated | 2015 (39th session) |

| Reference no. | 1446 |

| State Party | Jordan |

| Region | Arab States |

Al-Maghtas (Arabic: المغطس), meaning "baptism" or "immersion" in Arabic, is an archaeological World Heritage site in Jordan on the east bank of the Jordan River, officially known as Baptism Site "Bethany Beyond the Jordan" (Al-Maghtas). It is considered to be the original location of the Baptism of Jesus and the ministry of John the Baptist and has been venerated as such since at least the Byzantine period.[1]

Al-Maghtas includes two principal archaeological areas.[2] The remnants of a monastery on a mound known as Jabal Mar-Elias (Elijah's Hill) and an area close to the river with remains of churches, baptism ponds and pilgrim and hermit dwellings. The two areas are connected by a stream called Wadi Kharrar.[3]

The strategic location between Jerusalem and the King's Highway is already evident from the Book of Joshua report about the Israelites crossing the Jordan there. Jabal Mar-Elias is traditionally identified as the site of the ascension of the prophet Elijah to heaven.[4] The complete area was abandoned after the 1967 Six-Day War, when both banks of the Jordan became part of the frontline. The area was heavily mined then.[5]

After the signing of the Israel–Jordan peace treaty, de-mining of area took place after an initiative of Jordanian royalty, namely Prince Ghazi.[6] The site has then seen several archaeological digs, 4 papal visits and state visits and attracts tourists and pilgrimage activity.[7]

Etymology

Bethany, a name shared with the other town of this name located on the Mount of Olives, may come from beth-ananiah, Hebrew for "house of the poor/afflicted".[8]

Al-Maghtas is the Arabic word for a site of baptism or immersion.

Location of New Testament site

Two passages from the Gospel of John indicate a place "beyond the Jordan" or "across the Jordan":

- John 1:28: These things took place in Bethany beyond the Jordan, where John was baptising.

- John 10:40: He [Jesus] went away again across the Jordan to the place where John had been baptizing earlier, and he remained there.

Considering the viewpoint of the evangelist, is likely not to refer to the Bethany on the Mount of Olives near Jerusalem, today's Al-Eizariya, but to another Bethany, also known as Bethabara,[9] located on the eastern bank of the Jordan.[10]

Geography

Al-Maghtas is located on the eastern bank of the Jordan River, 9 kilometres (5.6 mi) north of the Dead Sea and 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) southeast of Jericho. The entire site, which is spread over an area of 533.7 hectares (ca. 5.3 km2 or 1,32 acres), has two distinct zones – Tell al-Kharrar, also called Jabal Mar Elias (Elijah’s Hill), and the area close to the river (2 kilometres (1.2 mi) to the east), the Zor area, where the ancient Church of Saint John the Baptist is situated.[1][2]

The site is close to the ancient road between Jerusalem and Transjordan, via Jericho, across a Jordan River ford and connecting to other biblical sites such as Madaba, Mount Nebo and the King's Highway.[5]

While the initial site of veneration was on the eastern side of the River Jordan, focus had shifted to the western side by the 6th century.[11] The term Al-Maghtas itself has been used historically for the area stretching over both banks of the river. The western part, also known under the name Qasr el-Yahud, has been mentioned in the UNESCO proposal, but so far has not been declared as a World Heritage Site.[3][12]

In November 2015, the site became available on Google Street View.[13]

Religious significance

Israelites' crossing of the Jordan

According to the Hebrew Bible, Joshua instructed the Israelites how to cross the Jordan by following the priests who were carrying the Ark of the Covenant through the river, thus making its waters stop their flow (Joshua 3, mainly Joshua 3:14–17Template:Bibleverse with invalid book). Ancient traditions identified Al-Maghtas, known in antiquity as bet-'abarah[14] or Bethabara, "House of the Crossing" (see Madaba Map), as the place where the people of Israel and later Prophet Elijah crossed the Jordan River and entered the Promised Land.[15][16]

Prophet Elijah

The Hebrew Bible also described how Prophet Elijah, accompanied by Prophet Elisha, stopped the waters of the Jordan, crossing to the eastern side, and then ascended to heaven in a chariot of fire. Elisha, now his heir, again separated the waters and crossed back (Kings II, 2:8–14Template:Bibleverse with invalid book). An ancient Jewish tradition identified the site of crossing with the same one used by Joshua, thus with Al-Maghtas, and the site of Elijah's ascension with Tell el-Kharrar, also known as Jabal Mar Elias, "Hill of Prophet Elijah".[17]

Baptism of Jesus

John probably baptised in springs and brooks at least as much as he did in the more dangerous Jordan River. The concrete example is "Aenon near Salim" of John 3:23Template:Bibleverse with invalid book, where "aenon" stands for spring. At Al-Maghtas there is a short brook, Wadi al-Kharrar, which flows to the Jordan, and is associated with the baptism activities of John.[4]

History and achaeology

Pre-Roman settlement

The archaeological excavations have unearthed antiquities which attest to the conclusion that this site was first settled by a small group of agriculturists during the Chalcolithic period, around 3,500 BC. There are again signs of settlement from the Hellenistic period.[1]

Roman and Byzantine periods

The site contains buildings with both aspects of a Jewish mikveh (ritual bath) resembling Second Temple period pools from Qumran, and later of Christian use, with large pools for baptism, linking both customs.[18]

Possibly in the 2nd-3rd and certainly starting with the 5th-6th centuries, Christian religious structures were built at Tell al-Kharrar.[19] It must be remembered that in the 1st-4th centuries of the Christian Era, Christianity was often persecuted by the Roman state, and only after it became first tolerated and then outright the state religion of the Roman, or now so-called Byzantine Empire, open Christian worship became possible.

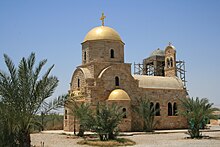

Archaeological excavations also established that the hill of Tell al-Kharrar, known as Elijah's Hill, was venerated as the spot from which Prophet Elijah ascended to heaven. In the 5th century, in commemoration, a Byzantine monastery was erected here. The archaeologists have named it the "Monastery of Rhetorios" after a name from a Byzantine mosaic inscription.[1][2]

Byzantine emperor Anastasius erected between 491–518, on the eastern banks of the River Jordan, a first church dedicated to St. John the Baptist. However, due to two flood and earthquake events the church was destroyed. The church was reconstructed three times, until it crumbled, together with the chapel built over piers, during a major flood event in the 6th or 7th century.[1]

The pilgrimage sites have shifted during history. The main Christian archaeological finds from the Byzantine and possibly even Roman period indicated that the initial venerated pilgrimage site was on the east bank, but by the beginning of the 6th century the focus had moved onto the more accessible west bank of the river.[11]

During the Byzantine period the site was a popular pilgrimage centre. The Persian devastation of 614, river floodings, earthquakes and Muslim penetration put an end to Byzantine building activity on the east bank of the Jordan River, particularly in the Wadi al- Kharrar area.[20]

Early Muslim period

The Muslim conquest put an end to Byzantine building activity on the east bank of the Jordan River, but several of the Byzantine structures remained in use during the Early Islamic period. With time worship took place just across the river on the western side at Qasr el-Yahud.[21] After 670 AD the commemoration of the baptism site moved to the western side.[20]

Mamluk and Ottoman periods

The structures were rebuilt many times but were finally deserted by end of the 15th century.[1]

In the 13th century an Orthodox monastery was built over remnants of an earlier Byzantine predecessor,[1] but how long it lasted is not known. However, pilgrimage to the site declined and according to one pilgrim the site was in ruins in 1484. From the 15th to the 19th century there were hardly any visits by pilgrims to the site. A small chapel dedicated to St. Mary of Egypt, a hermit from the Byzantine period, was built during the 19th century and was also destroyed in the 1927 earthquake.[22][23][24][25][26]

In the early part of the twentieth century a farming community had occupied the area east of the Jordan River.[1]

Rediscovery after 1994 and tourism

As a result of the Six-Day War in 1967, the river became the ceasefire line and both banks became militarised and inaccessible to pilgrims. After 1982, while Qasr el-Yahud was still off-limits, Israel enabled Christian baptisms at the Yardenit site further north.[27] Following the Israel–Jordan peace treaty in 1994 access to Al-Maghtas was restored after Prince Ghazi of Jordan, who is deeply interested in religious history, visited the area in the company of a Franciscan archaeologist who had convinced him to take a look at what was thought to be the baptism site. When they found evidence of Roman-period habitation, this was enough to encourage de-mining and further development.[26] Soon afterwards, there were several archaeological digs[6] led by Dr. Mohammad Waheeb who rediscovered the ancient site in 1997.[7] The 1990s marked the period of archaeological excavations of the site followed by primary conservation and restoration measures during the early 21st century.[1] Jordan fully reopened al-Maghtas in 2002. This was then followed by the Israeli-run western side, known as Qasr el-Yahud, which was opened for daily visits in 2011 - the traditional Epiphany celebrations had already been allowed to take place since 1985, but only at the specific Catholic and Orthodox dates and under military supervision.[21][28] In 2007, a documentary film entitled The Baptism of Jesus Christ – Uncovering Bethany Beyond the Jordan was made about the site.[29][30][30]

The western side attracts larger touristic interest than its Jordanian counterpart, half a million visitors compared to some ten thousands on the Jordanian side.[21] Other estimates put the numbers as 300,000 on the Israeli side and 100,000 on the Jordanian side.[22][31] To put that into perspective, Yardenit has more than 400.000 visitors p.a.[27]

In the millennium year 2000, John Paul II was the first pope to visit the site.[32] Several more papal and state visits were to follow.[6] In 2002 Christians commemorated the baptism of Christ at the site for the first time since its rediscovery. Since then, thousands of Christian pilgrims from around the world annually have marked Epiphany at Bethany Beyond the Jordan.[7] Also in 2002, the Baptism Site opened for daily visits, attracting a constant influx of tourists and pilgrimage activity. In 2015, the UNESCO declared the Al-Maghtas site on the east bank of the River Jordan as a World Heritage Site, while Qasr el-Yahud was left out.[22]

Features

Archaeological excavations at the site of the 1990s have revealed religious edifices of Roman and Byzantine period which include "churches and chapels, a monastery, caves used by hermits and pools", which were venues of baptisms.[2] The excavations have been supported by institutions from various countries, such as the US and Finland, and by the German Protestant Institute.[4]

Tell el-Kharrar or Elijah's Hill and the baptismal pools

The digs unearthed three churches, three baptismal pools, a circular well and an external compound encircling the hill. Existence of water supply sourced from springs and conveyed to the baptism sites through ceramic pipes was revealed;[4] this facility is available even now.[1]

Bankside area (Zor)

In the Zor area of the site, the finds covered a church with a hall with columns, a basilica church known as the Church of St. John the Baptist, the Lower Basilica Church with marble floors having geometrical designs. Also exposed were the Upper Basilica Church, the marble steps, the four piers of the Chapel of the Mantle, the Small Chapel, the Laura of St. Mary of Egypt, and a large pool. The stairway of marble steps was built in 570 AD. 22 of the steps are made of black marble. The stairway leads to the Upper Basilica and a baptismal pool. This pool had once four piers that supported the Chapel of the Mantle.[1]

Hermitages

The Quattara hills revealed a number of monk caves, also known as hermit cells, which are 300 metres (980 ft) away from the Jordan River. When the caves were in use access was through a rope way or by stairway or ladders from the western and south-western sides, but none of these are seen now. Each of these caves was carved with a semicircular niche on its eastern wall. The cave has two chambers, one for prayer and another a living space for the monks.[1]

Tombs

Tombs unearthed in and outside the churches are believed to be of monks of the churches. These tombs are of the Byzantine and early Islamic periods.(5th–7th centuries). Numismatics finds of coins and ceramics at the site are epigraphic proofs of the site's history.[1]

Authenticity

The Jordanian, eastern side of the traditional baptism area of Al-Maghtas has been accepted by the majority of Christians as the authentic site of the baptism of Jesus.[3] The Baptism Site's official website is showing 13 authentication testimonials from representatives of major international denominations.[33]

UNESCO involvement

In 1994, UNESCO sponsored archaeological excavations in the area.[1] Initially UNESCO had listed the site in the tentative list on 18 June 2001 and a new nomination was presented on 27 January 2014. ICOMOS evaluated the report presented by Jordan from 21–25 September 2014.[1] The finds are closely associated with the commemoration of the baptism. Following this evaluation, the site was inscribed by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site under the title "Bethany Beyond the Jordan (Al-Maghtas)". It was inscribed as a cultural property under UNESCO Criteria (iii) and (vi).[2][12] The Palestinian Tourist agency deplores the UNESCO's decision to leave out the western baptismal site.[21] During the negotiations of the UNESCO listings, the original proposal to UNESCO stated the will to expand the site in the future in cooperation with "the neighboring country".[22]

Site management

The Baptism Site is operated by the Baptism Site Commission, an independent board of trustees appointed by H.M. King Abdullah II bin Al-Hussein.[34]

See also

- Ænon, a baptism site mentioned in the Gospel of John

- Baptism of Jesus

- Bethabara, a name used by some versions of the New Testament for the site of Jesus' baptism

- List of World Heritage Sites in Jordan

- Qasr el-Yahud, the West Bank side of Al Maghtas

- New Testament places associated with Jesus

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Evaluations of Nominations of Cultural and Mixed Properties to the World Heritage List: ICOMOS Report" (pdf). UNESCO Organization. August 2014. pp. 49–50. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ a b c d e "Baptism Site "Bethany Beyond the Jordan" (Al-Maghtas) – UNESCO World Heritage Centre". UNESCO. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ a b c Tharoor, Ishaan (July 13, 2015). "U.N. backs Jordan's claim on site where Jesus was baptized". The Washington Post.

- ^ a b c d Rosemarie Noack (22 December 1999). "Wo Johannes taufte". ZEIT ONLINE. Retrieved 2015-12-09.

- ^ a b "UNESCO backs Jordan River as Jesus' baptism site". Al Arabiya News. Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Associated Press. 13 July 2015.

- ^ a b c http://www.jordantimes.com/news/local/adding-baptism-site-world-heritage-list-grants-it-further-int%E2%80%99l-recognition%E2%80%99

- ^ a b c http://www.jordantimes.com/news/local/catholics-celebrate-epiphany-coexistence-faiths-baptism-site#sthash.arczgCyW.dpuf

- ^ Watson E. Mills, ed. (2001). Mercer Dictionary of the Bible. Macon, GA, US: Mercer University Press. p. 99. ISBN 9780865543737.

- ^ John 1:28 in Stephanus' 1550 New Testament and in the Geneva Bible, King James Version and other translations

- ^ Charles Miller, S.M. (January–February 2002). "Bethany Beyond the Jordan". CNEWA WORLD. Catholic Near East Welfare Association (CNEWA). Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- ^ a b Eugenio Alliata, OFM (1999). "The Pilgrimage Route During Byzantine Period in Transjordan". The Madaba Map Centenary. Jerusalem: Studium Biblicum Franciscanum – Jerusalem. p. 122. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

... the construction of a new church on the more accessible west bank of the river succeeded in attracting the toponym as it appears also in the Madaba map. The new church of the "Prodromos" was built by the Emperor Anastasius (AD 491–518) as the pilgrim and archdeacon Theodosius [518–530] reports. Starting from the sixth century a major festival took place there on the feast of Epiphany (January 6). It is well described by the pilgrim of Piacenza [570s] and, without a doubt, many people also from the eastern side of the Jordan took part in this annual event.

- ^ a b "Jesus' Baptism at Jordan River Named 'World Heritage Site;' but UNESCO Says Only on Jordanian Side, Not Israel". Christian Post. Retrieved 2015-12-07.

- ^ http://www.google.com/maps/streetview/#jordan-highlights/the-baptismal-site

- ^ Othmar Keel, Max Küchler and Christoph Uehlinger, Orte und Landschaften der Bibel Volume 2, p. 530

- ^ Rami G. Khouri (1999). "Bethany beyond the Jordan: John the Baptist's settlement at "Bethany beyond the Jordan" sheds new light on baptism tradition in Jordan". The American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR). Retrieved 11 March 2004.

- ^ Avraham Negev and Shimon Gibson (2001). Beth Abara. New York and London: Continuum. p. 75. ISBN 0-8264-1316-1.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ http://en.radiovaticana.va/news/2014/05/24/pope_meets_refugees,_disabled_youth_near_jordans_banks/1100933

- ^ Lawrence, Jonathan David (2006-01-01). Washing in Water: Trajectories of Ritual Bathing in the Hebrew Bible and Second Temple Literature. Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 9781589831995.

- ^ Rami G. Khouri (1999). "Bethany beyond the Jordan: John the Baptist's settlement at "Bethany beyond the Jordan" sheds new light on baptism tradition in Jordan". The American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR). Retrieved 11 March 2004.

In this same area, south of the main tell, the excavators identified another rectangular building made of undressed field stones, measuring nearly 12 x 8 metres in size. The simple white mosaic floor of the building was slightly disfigured by the remains of ashes from the structure's final destruction - probably burnt roof beams. Dr Waheeb interprets this as a Christian pilgrims' 'prayer hall', rather than a church or chapel, on the basis of its location and style of construction. The evidence from the excavations suggests a slightly earlier date for this structure than the other parts of the monastery, probably in the Late Roman period (2nd-3rd Century AD?) when Christians were known to be active in this region. If so, it could be the earliest church or Christian prayer hall yet discovered in Jordan and the whole world. [...] Dr Waheeb tends to think that the three pools and the churches on the tell were built in the Late Byzantine period (5th-6th Century AD)....

- ^ a b Mohammad Waheeb: The Discovery of Bethany Beyond the Jordan River (Wadi Al- Kharrar) Dirasat Human and Social Sciences, Volume 35, No.1, 2008– 115 -

- ^ a b c d The Associated Press (13 July 2015). "No evidence, but UN says Jesus baptized on Jordan's side of river, not Israel's". Times of Israel. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- ^ a b c d "UNESCO settles Jesus baptism site controversy, says Jordan". ynet. Retrieved 2015-12-09.

- ^ Mohammad Waheeb (July 2012). "The Discovery of Elijah's Hill and John's Site of the Baptism, East of the Jordan River from the Description of Pilgrims and Travellers". Asian Social Science. 8 (8). Canadian Center of Science and Education: 206–207. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

From all the above it is evident that from the sixth century onwards, the monastery of Saint John on the east side of the Jordan river remained the location where people placed the sanctuary of the baptism. Moreover, the texts tell of the existence of a second church on the eastern bank of the river in front of the Monastery of Saint John. During the crusades, the Jordan River became a frontier line between the Latin kingdom of Jerusalem and the Sultanate of Damascus. This political situation resulted in the abandonment of the sanctuaries on the east bank of the river and moving the ceremonies to its west bank. This situation has continued until the present (Piccirillo 2006: 441).

- ^ Mohammad Waheeb. "Historical Background". Bethany (the project website of the chief archaeologist at Al-Maghtas, Dr. Mohammad Waheeb). Retrieved 11 March 2004.

After 670, gradually, baptism was gradually practiced in the western side.

- ^ [1]

- ^ a b Michele Piccirillo OFM (1999). "Aenon Sapsaphas and Bethabara". The Madaba Map Centenary 1897-1997. Jerusalem: Franciscan Printing Press. pp. 219–220. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

In 1106 Abbot Daniel a Russian pilgrim was well impressed by the place.... The place was later abandoned for security reasons. However, the memory of the place was not lost;.... in the year 1400 AD....

- ^ a b "Baptism battles on River Jordan". BBC. 2009-09-15. Retrieved 2015-12-09.

- ^ Erhard Gorys (1996). Heiliges Land Kunst-Reiseführer (Holy Land: A culture guide) (in German). Cologne: DuMont. p. 160. ISBN 3-7701-3860-0. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

1933 bauten die Franziskaner südlich vom Johanneskloster eine Kapelle. Es folgen eine Kirche der Syrer und eine Kapelle der Kopten. (Translation: In 1933 the Franciscans built a chapel south of the St John Monastery. The Syriacs followed with a church and the Copts with a chapel.)

- ^ "Baptism of Jesus Christ film". Ten Thousand Films. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 2011-07-31.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Watch: Where Jesus was baptized". Catholic Sentinel Organization. 23 October 2015. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- ^ "World Heritage status confirms Jesus was not baptized in Israeli territory, Jordanian media reports say". Retrieved 2015-12-08.

- ^ "Bethany-beyond-the-Jordan Takes Centre Stage for Papal Visit". Ammon News. Amman, Jordon. April 22, 2009.

- ^ [The Baptism of Jesus Christ Bethany beyond the Jordan: Letters of authentication http://www.baptismsite.com/index.php/authentication.html]

- ^ History and Info: About us, accessed 10 February 2016