Amos Fries

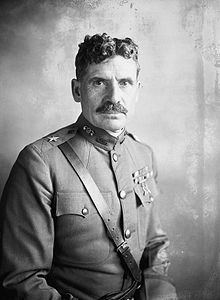

Amos A. Fries | |

|---|---|

Brig. Genl. A. A. Fries, 8/5/1921 | |

| Born | March 17, 1873 Viroqua, Wisconsin |

| Died | December 30, 1963 (aged 90) Washington, D. C. |

| Place of burial | |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Service | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1898–1929 |

| Rank | Major General |

| Commands | 1st Gas Regiment, Chemical Warfare Service |

| Battles / wars | Philippine-American War World War I |

| Awards | Distinguished Service Medal |

| Other work | Author Road/Bridge construction - Yellowstone Park |

Amos Alfred Fries was a general in the United States Army and 1898 graduate of the United States Military Academy. Fries was the second chief of the army's Chemical Warfare Service, established during World War I. Fries served under John J. Pershing in the Philippines and oversaw the construction of the roads and bridges in Yellowstone National Park. He eventually became an important commander in World War I. After he retired from the Army in 1929, Fries wrote two anti-communist books. He died in 1963 and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Early life

Amos Alfred Fries was born March 17, 1873 in Viroqua, Wisconsin.[1] His family moved to Missouri after he was born and then moved to Oregon. Fries earned an appointment to the United States Military Academy and graduated there in 1898.[2]

Military career

After graduating West Point Fries joined the Army Corps of Engineers and served in the Philippines during the Philippine-American War.[2] During that time he saw combat under the leadership of Captain John J. Pershing, later the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) commander during World War I.[2] From 1914 to 1917 Fries oversaw the construction of roads and bridges in Yellowstone National Park;[2] he gained some notoriety for that work.[3]

Fries arrived in Europe as World War I raged, he expected to do more engineering work but was instead thrust into heading the fledgling Gas Service Section, AEF.[2] The Gas Service Section was mostly constituted by the 1st Gas Regiment (originally the 30th Engineer Regiment (Gas and Flame)) and Fries commanded the section.[1] He became the chief of the Overseas Division of the Chemical Warfare Service in 1919,[1] and when William L. Sibert retired in 1919, Fries became the first peacetime overall chief of the Chemical Warfare Service the following year.[4][5] He served at that post until he retired from the Army in 1929.[1][6] For his work with the Chemical Warfare Service he was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal.[7]

"Anti-communism" and chemical warfare advocacy

During the "interwar period", the Chemical Warfare Service maintained its arsenal despite public pressure and presidential wishes in favor of disarmament. Fries viewed calls for chemical disarmament as a Communist plot.[6] As CWS chief, Fries created a secret military intelligence unit within the Chemical Warfare Service to monitor domestic subversion.[8] Fries accused the National Council for Prevention of War (NCPW) of being a Communist front.[9] He also leveled similar accusations at Florence Watkins, the executive secretary of the National Congress of Parent Teacher Associations. The pressure generated by Fries' accusations led to the National Congress of Parent Teacher Associations withdrawing its membership in the NCPW. The General Federation of Women's Clubs took the same action.[10]

In 1923 Fries' office distributed a "spider chart" to "patriotic groups" across the United States. The chart intended to show that all women's societies and church groups be regarded with suspicion concerning links to radical groups and Communist leadership.[11] The spider chart listed 21 individual women and 17 organizations, among them the Daughters of the American Revolution.[11] Later in his life, Fries wrote two anti-communist books, Communism Unmasked, published in 1937,[12] and Sugar Coating Communism.[1]

Later life and death

Fries died on December 30, 1963 and was buried at Arlington National Cemetery.[1]

Selected publications

- Chemical Warfare (1921), co-authored with Clarence J. West

- Communism Unmasked (1937)

- Sugar Coating Communism: A Plea for God and Country, Home and Family (c. 1930)

- Sugar Coating Communism for Protestant Churches: Chart Showing Interlocking Membership of Churchmen, Socialists, Pacifists, Internationalists, and Communists (chart - 1923)

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f Patterson, Michael R. "Amos Alfred Fries", arlingtoncemetery.net, accessed October 21, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e Russell, Edward. War and Nature, (Google Books), Cambridge University Press, 2001, p. 38, (ISBN 0521799376), accessed October 21, 2008.

- ^ Harber, Ludwig Fritz. The Poisonous Cloud (Google Books), Oxford University Press, 1986, p. 135. (ISBN 0198581424)., accessed October 21, 2008.

- ^ "General Sibert Resigns: Head of Army's Chemical Warfare Service Resented Transfer", The New York Times, April 7, 1920, accessed October 16, 2008.

- ^ Committee on Finance, United States Senate Hearings Before the Committee on Finance, United States Senate on the proposed Tariff Act of 1921, (Google Books), U.S. Government Printing Office, 1922, p. 374.

- ^ a b van Courtland Moon, John Ellis. "United States Chemical Warfare Policy in World War II: A Captive of Coalition Policy?" (JSTOR), The Journal of Military History, Vol. 60, No. 3. (July, 1996), pp. 495–511. Retrieved October 21, 2008.

- ^ Davis, Jr., Henry Blaine (1998). Generals in Khaki. Pentland Press, Inc. pp. 135-136. ISBN 1571970886. OCLC 40298151

- ^ Faith, Thomas Iain. "Under a Green Sea: The US Chemical Warfare Service 1917-1929". Thesis, George Washington University, 2008.

- ^ See also: Front organization.

- ^ Haar, Charlene K. The Politics of the PTA (Google Books), Transaction Publishers, 2002, pp. 61–62, (ISBN 0765808641).

- ^ a b Evans, Sara Margaret. Born for Liberty: A History of Women in America, (Google Books), Simon and Schuster, 1997, p. 190, (ISBN 0684834987).

- ^ Bendersky, Joseph W. The "Jewish Threat", (Google Books), Basic Books, 2000, p. 470, (ISBN 0465006183).

Further reading

- Fries, Amos A. "Address by Major General Amos A. Fries Chief of the Chemical Warfare Service at the Opening Exercises Army Industrial College, September 1, 1925", National Defense University, Library, accessed October 21, 2008.

- Fries, Amos A. Communism Unmasked, (Google Books), originally published 1937, Kessinger Publishing, 2007, (ISBN 1432506161).

- Staff. "Upholds Gas Warfare: Brigadier General Fries, Head of A.E.F. Service, Calls it Humane", The New York Times, February 17, 1919, accessed October 27, 2008.

- 1873 births

- 1963 deaths

- United States Army generals

- Burials at Arlington National Cemetery

- United States Military Academy alumni

- People from Viroqua, Wisconsin

- American military personnel of the Philippine–American War

- United States Army generals of World War I

- American anti-communists

- Chemical warfare

- Writers from Missouri

- Writers from Oregon

- Writers from Wisconsin

- Recipients of the Distinguished Service Medal (United States)