Anchorite

An anchorite or anchoret (female: anchoress; adj. anchoritic; from Template:Lang-grc, anachōrētḗs, "one who has retired from the world",[2][3] from the verb ἀναχωρέω, anachōréō, signifying "to withdraw", "to retire"[4]) is someone who, for religious reasons, withdraws from secular society so as to be able to lead an intensely prayer-oriented, ascetic, and—circumstances permitting—Eucharist-focused life. Whilst anchorites are frequently considered to be a type of religious hermit,[5] unlike hermits they were required to take a vow of stability of place, opting instead for permanent enclosure in cells often attached to churches. Also unlike hermits, anchorites were subject to a religious rite of consecration that closely resembled the funeral rite, following which—theoretically, at least—they would be considered dead to the world, a type of living saint. Anchorites had a certain autonomy, as they did not answer to any ecclesiastical authority other than the bishop.[6]

The anchoritic life is one of the earliest forms of Christian monastic living. In the Roman Catholic Church today it is one of the "Other Forms of Consecrated Life" and governed by the same norms as the consecrated eremitic life.[7] From the twelfth to the sixteenth century, female anchorites consistently outnumbered their male equivalents, sometimes by as many as four to one (in the thirteenth century), dropping eventually to two to one (in the fifteenth century). However, there is also a high number of anchorites whose sex is not recorded for these periods.[8]

Anchoritic life

The anchoritic life became widespread during the early and high Middle Ages. Examples of the dwellings of anchorites and anchoresses survive. A large number of these are in England. They tended to be a simple cell (also called anchorhold), built against one of the walls of the local village church.[9] In the Germanic lands from at least the tenth century it was customary for the bishop to say the office of the dead as the anchorite entered his cell, to signify the anchorite's death to the world and rebirth to a spiritual life of solitary communion with God and the angels. Sometimes, if the anchorite was walled up inside the cell, the bishop would put his seal upon the wall to stamp it with his authority. But some anchorites freely moved between their cell and the adjoining church.[10]

Most anchoritic strongholds were small, perhaps no more than 12 or 15 feet square, with three windows. Viewing the altar, hearing Mass, and receiving Holy Communion was possible through one small, shuttered window in the common wall facing the sanctuary, called a "hagioscope" or "squint". Anchorites would also provide spiritual advice and counsel to visitors through this window, as the anchorites gained a reputation for wisdom.[11] There was another small window that would have allowed access to those who saw to the anchorite's physical needs, like food and other necessities. The third window quite possibly faced the street but was covered with translucent cloth to allow light into the cell.[6]

Anchorites were supposed to remain in their cell in all eventualities. Some were even burned in their cells, which they refused to leave even when pirates or other attackers were looting and burning their towns.[12] They ate frugal meals, and spent their days both in contemplative prayer and interceding on behalf of others. Anchorites' bodily waste was managed by means of a chamber pot.[13]

In addition to being the crucial physical location wherein the anchorite could embark on the journey towards union with God and the culmination of spiritual perfection, the anchorhold also provided a spiritual and geographic focus for many of those people from the wider society who came to ask for advice and spiritual guidance. It is clear that, although set apart from the community at large by stone walls and specific spiritual precepts, the anchorite also lay at the very centre of that same community. The anchorhold was clearly also a communal 'womb' from which would emerge an idealized sense of a community's own reborn potential, both as Christians and as human subjects.[8]

An idea of their daily routine can be gleaned from an anchoritic Rule. The most widely known today is the early-thirteenth-century text known as Ancrene Wisse.[14] Another, less widely known, example is the rule known as De Institutione Inclusarum written around 1160–62 by Aelred of Rievaulx for his sister.[15] It is estimated that the daily set devotions detailed in Ancrene Wisse would take some four hours, on top of which anchoresses would listen to services in the church, and engage in their own private prayers and devotional reading.[16]

Famous anchorites

The earliest recorded anchorites lived in the third century AD; for example, St. Hilarion (Gaza, 291 – Cyprus, 371) was known as the founder of anchoritic life in Palestine (Catholic encyclopedia, ST. JEROME, Vita S. Hilarionis in P.L., III, 29-54).

The anchoritic life proved especially popular in England. Well-known anchorites include:

- Bede records that, prior to a conference in 602 with Augustine of Canterbury, British churchmen consulted an anchorite about whether to abandon their Celtic Church traditions for the Roman practices which Augustine was seeking to introduce.

- Towards the end of the seventh century, Guthlac, related by blood to the royal house of Mercia, withdrew from the monastery at Repton to an island in the Lincolnshire Fens, where he lived for some 15–20 years.[17]

- Wulfric of Haselbury was enclosed as an anchorite in a cell built against the church in his village of Haselbury.

- Christine Carpenter, who submitted a petition in 1329[18] and was granted permission to become the Anchoress of Shere Church[19] (aka. The Church of St. James), in the Borough of Guildford, England. She received her food and drink from friends and family through a metal grating on the outside wall. In the interior of the church a quatrefoil shape was cut out of the wall through which she could receive the Eucharist and a squint (or hagioscope) for her use for prayer and reflection. She left her cell, and in 1332 she applied again and was granted permission to be re-enclosed.[1]

- Margaret Kirkby (possibly 1322[20] to 1391–4), an anchoress at Hampole, Yorkshire for whom Richard Rolle wrote his vernacular guide The Form of Living.[21]

- Walter Hilton composed the first book of his Scale of Perfection for an unnamed enclosed woman.

- Julian of Norwich, whose writings have left a lasting impression on Christian spirituality.[22] Her cell, attached to St Julian's Church, Timberhill, Norwich, was destroyed during an air raid during World War II. The church itself was gutted but the original walls remain, and it was rebuilt. On the site of the cell is a modern shrine to Julian.

In total, there is evidence for the existence of around 780 anchorites on 600 sites in England between 1100 and 1539, when Henry VIII dissolved the monasteries and brought anchoritism in England to an end. Women were more numerous among the anchorites than men—considerably so in the thirteenth century.[23]

Good examples of English anchorholds can still be seen at Chester-le-Street in Durham, and at Hartlip in Kent.

Notable people

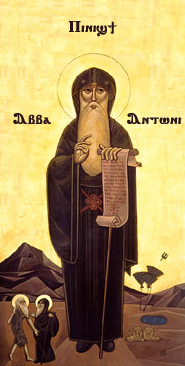

- Saint Anthony the Great

- Walter Hilton

- Julian of Norwich

- Margery Kempe

- Nazarena

- Richard Rolle

- Henry Suso

See also

- Ancrene Wisse

- Asceticism

- Book of the First Monks

- Cenobite

- Christian monasticism

- Christian mysticism

- The Cloud of Unknowing

- Consecrated life

- Hermit

- Immured anchorite

- Mystical theology

- Nazirite

- Shugendō

- Sadhu

- Stylite

Notes

- ^ a b Wyndham Thomas (2012). Robert Saxton: Caritas. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. pp. 16–20. ISBN 978-0-7546-6601-1.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "anchorite". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ ἀναχωρητής. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ^ ἀναχωρέω in Liddell and Scott

- ^ BBB Radio 4: Making History – Anchorites

- ^ a b LePan, Don (2011). The Broadview Anthology of British Literature. Broadview Press. p. 348.

- ^ The Code of Canon Law 1983, canon 603

- ^ a b Herbert McAvoy, Liz (2005). Anchorites, Wombs And Tombs : Intersections Of Gender And Enclosure In The Middle Ages. University of Wales. p. 13.

- ^ Tom Licence, Hermits and Recluses in English Society 950-1200, (Oxford, 2011), pp. 87-9

- ^ Licence, Hermits and Recluses, pp. 123, 120.

- ^ Licence, Hermits and Recluses, pp. 158-72

- ^ Licence, Hermits and Recluses, pp. 77-9

- ^ The Anchoress on line . Q&As Accessed October 2008

- ^ Ancrene Wisse

- ^ Translated by Mary Paul MacPherson in Treatises and the Pastoral Prayer, Cistercian Fathers Series 2, (Kalamazoo, 1971). In English the work is variously titled The Eremitical Life, The Rule of Life for a Recluse and The Training of Anchoresses.

- ^ Ancrene Wisse, trans Hugh White, (Penguin, 1993), p.viii

- ^ Ancrene Wisse, trans Hugh White, (Penguin, 1993), p.xiii

- ^ Petition to Become an Anchoress University of Saint Thomas–Saint Paul, MN , http://courseweb.stthomas.edu, 2003, 2012-04-22

- ^ History of Shere, sheredelight.com, 2011, 2012-04-22

- ^ Jonathan Hughes, ‘Kirkby, Margaret (d. 1391x4)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 accessed 6 May 2011

- ^ Ancrene Wisse, trans Hugh White, (Penguin, 1993), p.xiii

- ^ Revelations of Divine Love

- ^ Ancrene Wisse, trans Hugh White, (Penguin, 1993)

External links

Historical development

- Diocese of Kerry – Skellig Michael

- The Anchorhold at All Saints Church, King's Lynn, Norfolk

- Chapter 1 of The Rule of Saint Benedict re: Anchorites

- The Way of an Anchoress

- Anchorite Cell at St Luke's Church in Duston

- Marsha, Anchoritic Spirituality in Medieval England: The Form, the Substance, the Rule

- Rotha Mary Clay, Full Text plus illustrations, The Hermits and Anchorites of England.

- Rotha Mary Clay, The Hermits and Anchorites of England, Chapter VII: Anchorites in Church and Cloister

- Ancrene Wisse, Introduction

- anchorite?

- digitised copy of a British Library manuscript of the Ancrene Wisse, a rule for anchoresses written in the 13th century