Andrew Planta

Andrew Joseph Planta, also known as Andreas Joseph von Planta (1717–1773), was a Swiss Reformed pastor who emigrated to England, where he became librarian at the British Museum. He was born in Susch, studied theology in Zürich and worked as pastor in the Italian-speaking Protestant parish of Castasegna. He published an Italian psalter and book of prayers in 1740. In 1745, he obtained an MA degree at the University of Erlangen.

After working as an educator at the court in Ansbach, he moved to London in 1752 to take up the post of pastor of the German Reformed congregation. He became assistant librarian at the British Museum in 1758, reader and tutor to Queen Charlotte in the 1760s and was elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1770. Several of his daughters worked as governesses at court or in noble families. His son Joseph Planta succeeded him at the British Museum and later became its principal librarian.

Early life and family

[edit]

Planta was born on 4 August 1717 (O.S.) in Susch.[1] His father was the Landammann Joseph Planta (1692–1729) and his mother was Elisabeth Conrad from Fideris.[2][3] The Planta family was at this time one of the most important families of the Engadin area.[4] While there are unverified claims that the family is related to a Roman family of the same name that had dealings with Emperor Claudius,[5][6][7] the family is more reliably documented since 1139[2] or 1244.[4] Planta had four younger siblings; the youngest was Martin Planta[8] (1727–1772), a theologian, educator and scientist.[9]

Education and early career

[edit]

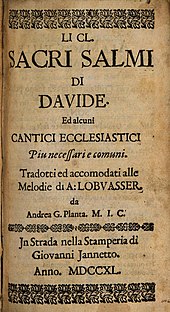

In 1734, Planta studied theology at the Schola Tigurina in Zürich; he passed an examination by the synod and was ordained in Ilanz in Grisons in 1735.[1][3][10] In 1736 or 1737, he became pastor of the parish of Castasegna,[11][3] one of very few parishes with an Italian-speaking Protestant population.[2] In 1739, he translated the metrical psalter of Ambrosius Lobwasser into Italian as Li CL sacri Salmi di Davide, ed alcuni cantici ecclesiastici,[12] which appeared together with an accompanying book of prayers (Preghiere sacre e divote) in 1740.[13] He also translated Johann Hübner's children's bible into Italian, which appeared in 1743 as Due volte cinquant' e due Lezioni sacre without acknowledgment of the translator, but the second Italian edition of 1785 and the Ladin edition of 1770 both credit Planta.[14]

In 1745, Planta went to the recently founded University of Erlangen, where he obtained an MA degree with a dissertation entitled Exercitatio Docimastica, Exhibens Delineationem Philosophiae Generalis (A docimastical exercise showing an outline of general philosophy).[15][16] Reports that he obtained a doctorate[17] or that he was professor of mathematics in Erlangen[4][2][18] are not correct.[16] From 1745, Planta worked as educator of prince Alexander at the Ansbach court of Charles William Frederick, Margrave of Brandenburg-Ansbach and his wife Princess Friederike Luise of Prussia.[19][17] He likely also taught mathematics at the Gymnasium Carolinum.[3][20]

Life in London

[edit]

After travelling to London, where his brother Martin had lived 1749–1750, with the permission of the Ansbach court, Planta became pastor of the German Reformed congregation at the Savoy Chapel in London in 1752, serving until 1772.[21][3][22] His inaugural sermon on 22 October 1752, Die Ordnung GOttes in der Gemeine. Das ist der Lehrer Pflicht und des Volcks Schuldigkeit was printed in London.[23] The family lived in Bloomsbury.[24] In 1757, Planta became French tutor to Mary Eleanor Bowes.[25] From 1758, he worked as an assistant librarian at the British Museum.[2][3] He was Assistant Keeper of Natural History 1758–1765 and Assistant Keeper of Printed Books 1765–1773.[26] After 1761, he served as reader and taught Italian to Queen Charlotte.[2][25] In 1765, during Leopold Mozart's journey to London with his family on their grand tour, Planta entertained the Mozart family at Montagu House and showed them around the museum, probably on the occasion of a gift of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's music to the museum.[27] In his Natural History role at the museum, Planta was succeeded by Daniel Solander and in Printed Books by his son Joseph Planta.[28] In 1768, Carl Gottfried Woide was appointed as assistant pastor; he later succeeded Planta as pastor of the German congregation.[20]

Planta was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society on 15 March 1770.[22] The citation on his election certificate was "Andrew Joseph Planta of the British Museum MA, & Minister of the German Reformed Church at the Savoy, a Gentleman of good learning, and well versed in natural knowledge, being desirous of becoming a member of the Royal Society; we recommend him, of our Personal acquaintance, as likely to be a valuable & useful member". His proposers were Gregory Sharpe, Gowin Knight, Henry Baker, Jerome de Salis, Joseph Ayloffe, Matthew Duane, Charles Morton, Samuel Harper, Matthew Maty, Richard Penneck, Henry Putman, Joshua Kirby and John Bevis.[22] Planta himself was one of the proposers when Johann Reinhold Forster was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in February 1772.[29]

Planta died on 25 February 1773.[30] His burial was on 3 March 1773 at the St George's, Bloomsbury church.[18]

Personal life and children

[edit]Planta married Margarete Scartazzini de Bolgiani from Bondo in 1738.[13][3] They had six daughters and one son.[31][32] Several of the daughters worked as governesses and educators for noble families;[33] Wendy Moore later wrote "the Planta family had a seemingly endless supply of talented daughters."[34] The family spoke Romansh at home also during their time in London.[35][24]

The oldest daughter Anna Planta was born in Castasegna.[36] In 1762, she married Christian Minnick or Minnicks,[33][36] and they emigrated to Pennsylvania.[37][a] The second child was Elizabeth Planta, born in 1740 or 1741.[38] In 1757, she became governess to Mary Eleanor Bowes.[39][25] From 1777, she was married to John Parish, who was Superintendent of Ordnance at the Tower of London.[40] The next child was the only son, Joseph Planta, born 10 February 1744 in Castasegna,[31][32] who succeeded his father at the British Museum and became its principal librarian. He died in 1827.[36] His younger sister Frederica Planta was born in 1750.[32] She later served as governess and English teacher of the daughters of George III and Queen Charlotte[41] but died in February 1778.[42] She was succeeded by her sister Margaret Planta ("Peggy")[41] who died in 1834.[43] The second youngest sister, Anna Elizabeth (Eliza) Planta, was born in London in 1757. She succeeded her sister Elizabeth as governess to Mary Eleanor Bowes' children from 1776,[33] but soon after married Reverend Henry Stephens.[44] She moved to Russia after 1789 to work for Catherine Shuvalova. Her daughter Elizabeth later married Mikhail Speransky but died soon after giving birth to a daughter, Elisabeth Bagréeff-Speransky in 1799.[45][35] The youngest daughter Ursula Barbara Planta,[46] who was left money in Mary Eleanor Bowes' will,[33] died in 1834.[47]

Notes

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Hartmann 1951, p. 198.

- ^ a b c d e f de Beer 1952, p. 11.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hächler 2011.

- ^ a b c Deplazes-Haefliger & Brunold 2001.

- ^ de Beer 1952, pp. 8–10.

- ^ Falkenstein 1830, p. 19.

- ^ von Planta 1892, pp. 1–6.

- ^ Hartmann 1951, p. 196.

- ^ Grunder 2010.

- ^ Truog 1902, p. 31.

- ^ Hartmann 1951, pp. 198–199.

- ^ Planta 1740.

- ^ a b Hartmann 1951, p. 199.

- ^ Bernhard 2013, pp. 203–205, 211.

- ^ Planta 1745.

- ^ a b Hartmann 1951, pp. 201–202.

- ^ a b von Planta 1892, p. 344.

- ^ a b Harris 2008.

- ^ Hartmann 1951, p. 201.

- ^ a b Hartmann 1951, p. 204.

- ^ Hartmann 1951, pp. 201–202, 204.

- ^ a b c de Beer 1952, p. 12.

- ^ Planta 1752.

- ^ a b Badilatti 2017, p. 9.

- ^ a b c Moore 2009, p. 29.

- ^ Miller 1974, p. 91.

- ^ King 1984, p. 20.

- ^ British Museum 1879, p. 42.

- ^ Hoare 1976, p. 68.

- ^ The Town and Country magazine 1773, p. 168.

- ^ a b von Planta 1993, p. 35.

- ^ a b c Hartmann 1951, p. 200.

- ^ a b c d Moore 2009, p. 340.

- ^ Moore 2009, p. 107.

- ^ a b Contti 2013.

- ^ a b c Hartmann 1951, p. 207.

- ^ a b Withington 1905, pp. 311–312.

- ^ Talbot 2017, p. 101.

- ^ Fraser 2004, p. 24.

- ^ Talbot 2017, p. 102.

- ^ a b Baudino & Carré 2017, p. 50.

- ^ Fraser 2004, p. 54.

- ^ The Lady's Magazine 1834, p. 318.

- ^ Moore 2009, p. 115.

- ^ Solodyankina 2010, p. 21.

- ^ Hartmann 1951, p. 206.

- ^ The Examiner 1834, p. 716.

Sources

[edit]- Badilatti, Michele (31 October 2017). "Die altehrwürdige Sprache der Söldner und Bauern – Die Veredelung des Bündnerromanischen bei Joseph Planta (1744–1827)". Swiss Academies Reports (in German). 12 (6). doi:10.5281/zenodo.1039850.

- Baudino, Isabelle; Carré, Jacques (2 March 2017). The Invisible Woman: Aspects of Women's Work in Eighteenth-Century Britain. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-88735-9.

- Bernhard, Jan-Andrea (2013). ""...der Jugend zum Besten abgefasset..."". Bündner Monatsblatt: Zeitschrift für Bündner Geschichte, Landeskunde und Baukultur (in German). 2013 (2). doi:10.5169/seals-513581.

- de Beer, Gavin Rylands (1 October 1952). "Andreas and Joseph Planta, FF. R. S". Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. 10 (1): 8–14. doi:10.1098/rsnr.1952.0003. S2CID 202575252.

- British Museum (1879). Statutes and rules for the British Museum : the 10th of May 1879. London: Printed by order of the trustees (by Woodfall and Kinder).

- Contti, Torlach Mac (1 May 2013). "Ils Plantas ell'Engheltiara ed ella Russia". Südostschweiz (in Romansh). Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- Deplazes-Haefliger, Anna-Maria; Brunold, Ursus (2001). "Planta". Neue Deutsche Biographie (in German). Vol. 20. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot. pp. 502–504.; (full text online)

- Falkenstein, Karl (18 January 1830). "Joseph Planta, Oberbibliothekar und erster Vorsteher des britischen Museums zu London". Bündnerisches Volksblatt zur Belehrung und Unterhaltung (in German). Verlag von A.T. Otto's seliger Wittwe.

- Fraser, Flora (2004). Princesses : the six daughters of George III. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-6108-5.

- Grunder, Hans-Ulrich (20 May 2010). "Martin von Planta". Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz (in German). Retrieved 24 November 2022.

- Hächler, Stefan (9 November 2011). "Andreas von Planta". Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz (in German). Retrieved 24 November 2022.

- Harris, P. R. (3 January 2008). "Planta, Joseph". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/22353. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Hartmann, Benedict (1951). "Beiträge zur Biographie Martin Plantas". Bündnerisches Monatsblatt (in German) (7–8): 193–207. doi:10.5169/seals-397506.

- Hoare, Michael Edward (1976). The Tactless Philosopher: Johann Reinhold Forster (1729-98). Hawthorne Press. ISBN 9780725601218.

- King, Alec Hyatt (1984). A Mozart legacy : aspects of the British Library collections. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-96201-6.

- Miller, Edward (1974). That noble cabinet : a history of the British Museum. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press. ISBN 978-0-8214-0139-2.

- Moore, Wendy (2009). Wedlock : the true story of the disastrous marriage and remarkable divorce of Mary Eleanor Bowes, Countess of Strathmore. New York: Three Rivers Press. ISBN 978-0-307-38336-5. OCLC 232980259.

- Planta, Andrea G. (1740). Li CL sacri Salmi di Davide, ed alcuni cantici ecclesiastici (in Italian). Strada: Stamperia di Giovanni Jannetto.

- Planta, Andreas Josephus (1745). Exercitatio Docimastica, Exhibens Delineationem Philosophiae Generalis (MA thesis) (in Latin). Erlangen.

- Planta, A. (1752). Die Ordnung Gottes in der Gemeine. Das ist, der Lehrer Pflicht, und des Volcks Schuldigkeit, wurde vorgestellet aus Malach. II. 7 in einer Einstands-Predig, zum Pfarr-Dienst der Evang. Reform. Hochteutschen Gemeinde zu London, anno 1752 d. 22 October (in German). London: Haberkorn und Gussen.

- Solodyankina, Olga Yu. (2010). "Widows from European countries working as governesses in Russia in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries" (PDF). Women's History Magazine. 2010 (63): 19–26.

- Talbot, Michael (2017). "Maurice Greene's Vocal Chamber Music on Italian Texts". Royal Musical Association Research Chronicle. 48: 91–124. doi:10.1080/14723808.2016.1271573. ISSN 1472-3808. S2CID 191988956.

- Truog, Jakob Rudolf (1902). "Die Bündner Prädikanten 1555–1901 nach den Matrikelbüchern der Synode". Jahresbericht der Historisch-Antiquarischen Gesellschaft von Graubünden (in German). 31. Chur: Buchdruckerei Sprecher & Valer. doi:10.5169/seals-595856.

- von Planta, Eleonore (1993). "Ein Bündner in England". Bündner Jahrbuch: Zeitschrift für Kunst, Kultur und Geschichte Graubündens (in German). 35: 34–38. doi:10.5169/seals-555573.

- von Planta, P. (1892). Chronik der Familie von Planta nebst verschiedenen Mittheilungen aus der Vergangenheit Rhätiens. Zürich: Orell Füssli. OCLC 5652037.

- Withington, Lothrop (1905). "Pennsylvania Gleanings in England (continued)". The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. 29 (3): 310–319. ISSN 0031-4587. JSTOR 20085295.

- "Births, marriages and deaths". The Lady's Magazine and Museum of the Belles-lettres, Fine Arts, Music, Drama, Fashions, Etc. J. Page. 1834.

- "Died". The Examiner. No. 1397. Open Court Publishing Co. 9 November 1834. p. 716. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- "Deaths". The Town and Country magazine. March 1773. pp. 167–168.