Antinous

Antinous (also Antinoüs or Antinoös; Ancient Greek: Ἀντίνοος; 27 November, c. 111 – before 30 October 130[1]) was a Bithynian Greek youth and a favourite, or lover, of the Roman emperor Hadrian.[2] He was deified after his death, being worshiped in both the Greek East and Latin West, sometimes as a god (theos) and sometimes merely as a hero (heros).[3]

Little is known of Antinous' life, although it is known that he was born in Claudiopolis (present day Bolu, Turkey), in the Roman province of Bithynia. He likely was introduced to Hadrian in 123, before being taken to Italy for a higher education. He had become the favourite of Hadrian by 128, when he was taken on a tour of the Empire as part of Hadrian's personal retinue. Antinous accompanied Hadrian during his attendance of the annual Eleusinian Mysteries in Athens, and was with him when he killed the Marousian lion in Libya. In October 130, as they were part of a flotilla going along the Nile, Antinous died amid mysterious circumstances. Various suggestions have been put forward for how he died, ranging from an accidental drowning to an intentional human sacrifice.

Following his death, Hadrian deified Antinous and founded an organised cult devoted to his worship that spread throughout the Empire. Hadrian founded the city of Antinopolis close to Antinous's place of death, which became a cultic centre for the worship of Osiris-Antinous. Hadrian also founded games in commemoration of Antinous to take place in both Antinopolis and Athens, with Antinous becoming a symbol of Hadrian's dreams of pan-Hellenism.

Antinous became associated with homosexuality in Western culture, appearing in the work of Oscar Wilde and Fernando Pessoa.

Biography

The Classicist Caroline Vout noted that most of the texts dealing with Antinous's biography only dealt with him briefly and were post-Hadrianic in date, thus commenting that "reconstructing a detailed biography is impossible".[4] The historian Thorsten Opper noted that "Hardly anything is known of Antinous' life, and the fact that our sources get more detailed the later they are does not inspire confidence."[5] Antinous's biographer Royston Lambert echoed this view, commenting that information on him was "tainted always by distance, sometimes by prejudice and by the alarming and bizarre ways in which the principal sources have been transmitted to us."[6]

Childhood

It is known that Antinous was born to a Greek family in the city of Claudiopolis, which was located in the Roman province of Bithynia in what is now north-west Turkey.[7] The year of Antinous's birth is not recorded, although it is estimated that it was probably between 110 and 112 AD.[8] Early sources record that his birthday was in November, and although the exact date is not known, Lambert asserted that it was probably on 27 November.[8] Given the location of his birth and his physical appearance, it is likely that part of his ancestry was not Greek.[9]

There are various potential origins for the name "Antinous"; it is possible that he was named after the character of Antinous, who is one of Penelope's suitors in Homer's epic poem, the Odyssey. Another possibility is that he was given the male equivalent of Antinoë, a woman who was one of the founding figures of Mantineia, a city which probably had close relations with Bithynia.[8] Although many historians from the Renaissance onward asserted that Antinous had been a slave, only one of around fifty early sources claim this, and it remains unlikely, as it would have proved heavily controversial to deify a former slave in Roman society.[10] There is no surviving reliable evidence attesting to Antinous's family background, although Lambert believed it most likely that his family would have been peasant farmers or small business owners, thereby being socially undistinguished yet not from the poorest sectors of society.[11] Lambert also considered it likely that Antinous would have had a basic education as a child, having been taught how to read and write.[12]

Life with Hadrian

The Emperor Hadrian spent much time during his regime touring his Empire, and arrived in Claudiopolis in June 123, which was probably when he first encountered Antinous.[13] Given Hadrian's personality, Lambert thought it unlikely that they had become lovers at this point, instead suggesting it probable that Antinous had been selected to be sent to Italy, where he was probably schooled at the imperial paedagogium at the Caelian Hill.[14] Hadrian meanwhile had continued to tour the Empire, only returning to Italy in September 125, when he settled into his villa at Tibur.[15] It was at some point over the following three years that Antinous became his personal favourite, for by the time he left for Greece three years later, he brought Antinous with him in his personal retinue.[15]

"The way that Hadrian took the boy on his travels, kept close to him at moments of spiritual, moral or physical exaltation, and, after his death, surrounded himself with his images, shows an obsessive craving for his presence, a mystical-religious need for his companionship."

—Royston Lambert, 1984[16]

Lambert described Antinous as "the one person who seems to have connected most profoundly with Hadrian" throughout the latter's life.[17] Hadrian's marriage to Sabina was unhappy,[18] and there is no reliable evidence that he ever expressed a sexual attraction for women, in contrast to much reliable early evidence that he was sexually attracted to boys and young men.[19] For centuries, pederasty had long been socially acceptable among Greece's leisured and citizen classes, with an older erastes (aged between 20 and 40) undertaking a caring sexual relationship with an eromenos (aged between 12 and 18) and taking a key role in their education;[20] and Hadrian took Antinous as a favoured servant when they were aged about 48 and 13. Such a societal institution of pederasty was not indigenous to Roman culture, although bisexuality was the norm in the upper echelons of Roman society by the early 2nd century.[21]

It is known that Hadrian believed Antinous to be intelligent and wise, which might explain part of the attraction.[15] Another factor was potentially a shared love of hunting, which was seen as a particularly manly pursuit in Roman culture.[22] Although none survive, it is known that Hadrian wrote both an autobiography and erotic poetry about his boy favourites; it is therefore likely that he wrote about Antinous.[6] Early sources are explicit that the relationship between Hadrian and Antinous was sexual.[23] During their relationship, there is no evidence that Antinous ever used his influence over Hadrian for personal or political gain.[24]

In March 127, Hadrian – probably accompanied by Antinous – traveled through the Sabine area of Italy, Picenum, and Campania.[25] From 127 to 129 the Emperor was then afflicted with an illness that doctors were unable to explain.[25] In April 128 he laid the foundation stone for a temple of Venus and Rome in the city of Rome, during a ritual where he may well have been accompanied by Antinous.[25] From there, Hadrian went on a tour of North Africa, during which he was accompanied by Antinous.[26] In late 128 Hadrian and Antinous landed in Corinth, proceeding to Athens, where they remained until May 129, accompanied by Sabina, the Caeserii brothers, and Pedanius Fuscus the Younger.[27] It was in Athens in September 128 that they attended the annual celebrations of the Great Mysteries of Eleusis, where Hadrian was initiated into the position of epoptes in the Telesterion. It is generally agreed, although not proven, that Antinous was also initiated at that time.[28]

From there they headed to Asia Minor, settling in Antioch in June 129, where they were based for a year, visiting Syria, Arabia, and Judea. From there, Hadrian became increasingly critical of Jewish culture, which he feared opposed Romanisation, and so introduced policies banning circumcision and replacing the Jewish Temple with a Temple of Zeus-Jupiter. From there, they headed to Egypt.[29] Arriving in Alexandria in August 130, there they visited the sarcophagus of Alexander the Great. Although welcomed with public praise and ceremony, some of Hadrian's appointments and actions angered the city's Hellenic social elite, who began to gossip about his sexual activities, including those with Antinous.[30]

Soon after, and probably in September 130, Hadrian and Antinous traveled west to Libya, where they had heard of a Marousian lion causing problems for local people. They hunted down the lion, and although the exact events are unclear, it is apparent that Hadrian saved Antinous' life during their confrontation with it, before the beast itself was killed.[31] Hadrian widely publicised the event, casting bronze medallions of it, getting historians to write about it, commissioning Pancrates to author a poem about it, and having a tondo depicting it created which was later placed on the Arch of Constantine. On this tondo it was clear that Antinous was no longer a youth, having become more muscular and hairy, perceptibly more able to resist his master; and thus it is likely that his relationship with Hadrian was changing as a result.[31]

Death

In late September or early October 130, Hadrian and his entourage, among them Antinous, assembled at Heliopolis to set sail upstream as part of a flotilla along the River Nile. The retinue included officials, the Prefect, army and naval commanders, as well as literary and scholarly figures. Possibly also joining them was Lucius Ceionius Commodus, a young aristocrat whom Antinous might have deemed a rival to Hadrian's affections.[32] On their journey up the Nile, they stopped at Hermopolis Magna, the primary shrine to the god Thoth.[33] It was shortly after this, in October 130 – around the time of the festival of Osiris – that Antinous fell into the river and died, probably from drowning.[34] Hadrian publicly announced his death, with gossip soon spreading throughout the Empire that Antinous had been intentionally killed.[35] The nature of Antinous's death remains a mystery to this day, and it is possible that Hadrian himself never knew; however, various hypotheses have been put forward.[36]

One possibility is that he was murdered by a conspiracy at court. However, Lambert asserted that this was unlikely because it lacked any supporting historical evidence, and because Antinous himself seemingly exerted little influence over Hadrian, thus meaning that an assassination served little purpose.[37] Another suggestion is that Antinous had died during a voluntary castration as part of an attempt to retain his youth and thus his sexual appeal to Hadrian. However, this is improbable because Hadrian deemed both castration and circumcision to be abominations and as Antinous was aged between 18 and 20 at the time of death, any such operation would have been ineffective.[38] A third possibility is that the death was accidental, perhaps if Antinous was intoxicated. However, in the surviving evidence Hadrian does not describe the death as being an accident; Lambert thought that this was suspicious.[39]

Another possibility is that Antinous represented a voluntary human sacrifice. Our earliest surviving evidence for this comes from the writings of Dio Cassius, 80 years after the event, although it would later be repeated in many subsequent sources. In the second century Roman Empire, a belief that the death of one could rejuvenate the health of another was widespread, and Hadrian had been ill for many years; in this scenario, Antinous could have sacrificed himself in the belief that Hadrian would have recovered. Alternately, in Egyptian tradition it was held that sacrifices of boys to the Nile, particularly at the time of the October Osiris festival, would ensure that the River would flood to its full capacity and thus fertilise the valley; this was made all the more urgent as the Nile's floods had been insufficient for full agricultural production in both 129 and 130. In this situation, Hadrian might not have revealed the cause of Antinous's death because he did not wish to appear either physically or politically weak. Conversely, opposing this possibility is the fact that Hadrian disliked human sacrifice and had strengthened laws against it in the Empire.[40]

Deification and the cult of Antinous

Hadrian was devastated by the death of Antinous, and possibly also experiencing remorse.[41] In Egypt, the local priesthood immediately deified Antinous by identifying him with Osiris due to the manner of his death.[42] In keeping with Egyptian custom, Antinous' body was probably embalmed and mummified by priests, a lengthy process which might explain why Hadrian remained in Egypt until spring 131.[42] While there, in October 130 Hadrian proclaimed Antinous to be a deity and announced that a city should be built on the site of his death in commemoration of him, to be called Antinoopolis.[43] The deification of human beings was not uncommon in the Classical world, however the public and formal divinisation of humans was reserved for the Emperor and members of the imperial family; thus Hadrian's decision to declare Antinous a god and create a formal cult devoted to him was highly unusual, and he did so without the permission of the Senate.[44] Although the cult of Antinous therefore had connections with the imperial cult, it remained separate and distinct.[45] Hadrian also identified a star in the sky between the Eagle and the Zodiac to be Antinous,[46] and came to associate the rosy lotus that grew on the banks of the Nile as being the flower of Antinous.[47] One of Hadrian's attempts at extravagant remembrance failed, when the proposal to create a constellation of Antinous being lifted to heaven by an eagle (the constellation Aquila) failed of adoption.[citation needed][disputed – discuss]

It is unknown exactly where Antinous' body was buried. It has been argued that either his body or some relics associated with him would have been interred at a shrine in Antinopolis, although this has yet to be identified archaeologically.[48] However, a surviving obelisk contains an inscription strongly suggesting that Antinous' body was interred at Hadrian's country estate, the Villa Adriana at Tibur in Italy.[49]

It is unclear whether Hadrian genuinely believed that Antinous had become a god.[50] He would have also had political motives for creating the organised cult, for it enshrined political and personal loyalties specifically to him.[51] In October 131 he proceeded to Athens, where from 131-32 he founded the Panhellenion, an attempt to foster Greek self-consciousness, erode the feuding endemic to the Greek city-states, and promote the worship of the ancient gods; being Greek himself, the god Antinous helped Hadrian's cause in this, representing a symbol of pan-Hellenic unity.[52] In Athens, Hadrian also established a festival to be held in honour of Antinous in October, the Antinoeia.[53]

Antinous was understood differently by his various worshippers, in part due to regional and cultural variation. In some inscriptions he is identified as a divine hero, in others as a god, and in others as both a divine hero and a god. Conversely, in many Egyptian inscriptions he is described as both a hero and a god, while in others he was seen as a full god, and in Egypt, he was often understood as a daemon.[54] Inscriptions indicate that Antinous was seen primarily as a benevolent deity, who could be turned to aid his worshippers.[55] He was also seen as a conqueror of death, with his name and image often being included in coffins.[56]

Antinopolis

The city of Antinopolis was erected on the site of Hir-we. All previous buildings were razed and replaced, with the exception of the Temple of Ramses II.[50] Hadrian also had political motives for the creation of Antinopolis, which was to be the first Hellenic city in the Middle Nile region, thus serving as a bastion of Greek culture within the Egyptian area. To encourage Egyptians to integrate with this imported Greek culture, he permitted Greeks and Egyptians in the city to marry and allowed the main deity of Hir-we, Bes, to continue to be worshipped in Antinopolis alongside the new primary deity, Osiris-Antinous.[57] He encouraged Greeks from elsewhere to settle in the new city, using various incentives to do so.[58] The city was designed on a gridiron plan that was typical of Hellenic cities, and embellished with columns and many statues of Antinous, as well as a temple devoted to the deity.[59]

Hadrian proclaimed that games would be held at the city in Spring 131 in commemoration of Antinous. Known as the Antinoeia, they would be held annually for several centuries, being noted as the most important in Egypt. Events included athletic competitions, chariot and equestrian races, and artistic and musical festivals, with prizes including citizenship, money, tokens, and free lifetime maintenance.[60]

Antinopolis continued to grow into the Byzantine era, being Christianised with the conversion of the Empire, however it retained an association with magic for centuries to come.[61] Over the centuries, stone from the Hadrianic city was removed for the construction of homes and mosques.[62] By the 18th century, the ruins of Antinopolis were still visible, being recorded by such European travelers as Jesuit missionary Claude Sicard in 1715 and Edme-François Jomard the surveyor circa 1800.[63] However, in the 19th century, Antinopolis was almost completely destroyed by local industrial production, as the chalk and limestone was burned for powder while stone was used in the construction of a nearby dam and sugar factory.[64]

The cult's spread

Hadrian was keen to disseminate the cult of Antinous throughout the Roman Empire. He focused on its spread within the Greek lands, and in Summer 131 travelled these areas promoting it by presenting Antinous in a syncretised form with the more familiar deity Hermes.[65] On a visit to Trapezus in 131, he proclaimed the foundation of a temple devoted to Hermes, where the deity was probably venerated as Hermes-Antinous.[66] Although Hadrian preferred to associate Antinous with Hermes, he was far more widely syncretised with the god Dionysus across the Empire.[67] The cult also spread through Egypt, and within a few years of its foundation, altars and temples to the god had been erected in Hermopolis, Alexandria, Oxyrhynchus, Tebytnis, Lykopolis, and Luxor.[65]

The cult of Antinous was never as large as those of well established deities such as Zeus, Dionysus, Demeter, or Asclepios, or even as large as those of cults which were growing in popularity at that time, such as Isis or Serapis, and was also smaller than the official imperial cult of Hadrian himself.[68] However, it was able to spread throughout the Empire, with traces of the cult having been found in at least 70 cities, although its strength was far greater in certain regions than others.[68] Although the adoption of the Antinous cult was in some cases done to please Hadrian, the evidence makes it clear that the cult was also genuinely popular among the different societal classes in the Empire.[69] Part of the appeal was that Antinous had once been human himself, and thus was more relatable than many other deities.[70] In Egypt, Athens, Macedonia, and Italy, children would be named after the deity.[71]

At least 28 temples were constructed for the worship of Antinous throughout the Empire, although most were fairly modest in design; those at Tarsos, Philadelphia, and Lanuvium consisted of a four-column portico. It is likely however that those which Hadrian was directly involved in, such as at Antinopolis, Bithynion, and Mantineria, were often grander, while in the majority of cases, shrines or altars to Antinous would have been erected in or near the pre-existing temples of the imperial cult, or Dionysus or Hermes.[72] Worshippers would have given votive offerings to the deity at these altars; there is evidence that he was given gifts of food and drink in Egypt, with libations and sacrifices probably being common in Greece.[73] Priests devoted to Antinous would have overseen this worship, with the names of some of these individuals having survived in inscriptions.[73] There is evidence of oracles being present at a number of Antinoan temples.[73]

Sculptures of Antinous became widespread, with Hadrian probably having approved a basic model of Antinous' likeness for other sculptors to follow.[53][74] These sculptures were produced in large quantities between 130 and 138, with estimates being in the region of around 2000, of which at least 115 survive.[75] 44 have been found in Italy, half of which were at Hadrian's Villa Adriana, while 12 have been found in Greece and Asia Minor, and 6 in Egypt.[76] Over 31 cities in the Empire, the majority in Greece and Asia Minor, issued coins depicting Antinous, chiefly between the years 134–35. Many were designed to be used as medallions rather than currency, some of them deliberately made with a hole so that they could be hung from the neck and used as talismans.[77][74] Most production of Antinous-based artefacts ceased following the 130s, although such items continued to be used by the cult's followers for several centuries.[78]

Games held in honour of Antinous were held in at least 9 cities, and included both athletic and artistic components.[79] The games at Bythynion, Antinopolis, and Mantineia were still active by the early third century, while those at Athens and Eleusis were still operating in 266–67.[80] Rumours spread throughout the Empire that at Antinous' cultic centre in Antinopolis, there were "sacred nights" characterised by drunken revelries, perhaps including sexual orgies.[81]

Condemnation and decline

The cult of Antinous was criticised by various individuals, both pagan and Christian.[82] Critics included followers of other pagan cults, such as Pausanias,[83] Lucian, and the Emperor Julian, who were all sceptical about the apotheosis of Antinous, as well as the Sibylline oracles, who were critical of Hadrian more generally. The pagan philosopher Celsus also criticised it for what he perceived as the debauched nature of its Egyptian devotees, arguing that it led people into immoral behaviour, in this way comparing it to Christianity.[82] Surviving examples of Christian condemnation of the Antinous cultus come from figures like Tertullian, Origen, Jerome, and Epiphanios. Viewing the religion as a blasphemous rival to Christianity, they insisted that Antinous had simply been a mortal human and condemned his sexual activities with Hadrian as immoral. Associating his cult with malevolent magic, they argued that Hadrian had imposed his worship through fear.[84]

During the struggles between Christians and pagans in Rome during the fourth century CE, Antinous was championed by members of the latter. As a result of this, the Christian poet Prudentius denounced his worship in 384, while a set of seven contorniates depicting Antinous were issued, based upon the designs of those issued in the 130s.[85] Many sculptures of Antinous were destroyed by Christians, as well as by invading barbarian tribes, although in some instances were then re-erected; the Antinous statue at Delphi had been toppled and had its forearms broken off, before being re-erected in a chapel elsewhere.[86] Many of the images of Antinous remained in public places until the official prohibition of non-Christian pagan religions under the reign of Emperor Theodosius in 391.[85]

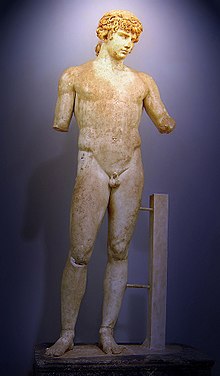

Antinous in Roman sculpture

Hadrian "turned to [Greek sculptors] to perpetuate the melancholy beauty, diffident manner, and lithe and sensuous frame of his boyfriend Antinous,"[87] creating in the process what has been described as "the last independent creation of Greco-Roman art".[88] It is traditionally assumed that they were all produced between Antinous' death in 130 and that of Hadrian in 138, on the grounds that no-one else would be interested in commissioning them.[89] The assumption is that official models were sent out to provincial workshops all over the empire to be copied, with local variations permitted.[90] It has been asserted that many of these sculptures "share distinctive features – a broad, swelling chest, a head of tousled curls, a downcast gaze – that allow them to be instantly recognized".[91]

By 2005, Classicist Caroline Vout could note that more images have been identified of Antinous than of any other figure in classical antiquity with the exceptions of Augustus and Hadrian.[92] She also asserted that the Classical study of these Antinous images was particularly important because of his "rare mix" of "biographical mystery and overwhelming physical presence".[92]

Lambert believed that the sculptures of Antinous "remain without doubt one of the most elevated and ideal monuments to pederastic love of the whole ancient world",[93] also describing them as "the final great creation of classical art".[94]

There are also statues in many archaeological museums in Greece including the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, the archaeological museums of Patras, Chalkis and Delphi. Although these may well be idealised images, they demonstrate what all contemporary writers described as Antinous's extraordinary beauty. Although many of the sculptures are instantly recognizable, some offer significant variation in terms of the suppleness and sensuality of the pose and features versus the rigidity and typical masculinity. In 1998 monumental remains were discovered at Hadrian's Villa that archaeologists claimed were from the tomb of Antinous, or a temple to him,[95] though this has been challenged both because of the inconclusive nature of the archaeological remains and the overlooking of patristic sources (Epiphanius, Clement of Alexandria) indicating that Antinous was buried at his temple in Antinopolis, the Egyptian city founded in his honor.[96]

-

As Bacchus, Vatican

-

As Bacchus, Vatican

-

From Delphi

-

Antinous Mondragone at the Louvre Museum

-

Antinous Ecouen, from Villa Adriana at Tivoli

-

Bust of Antinous in the Palazzo Altemps museum in Rome

-

Vatican Museums, colossal bust, from Villa Adriana

-

As Bacchus, Capitoline Museums

-

The Antinous Braschi type (Louvre)

-

Antinous as a priest of the imperial cult (Louvre)

-

Capitoline Antinous, Capitoline Museums, from the Villa Adriana

-

Villa Albani relief from the Torlonia collection, Rome

-

Relief, as Sylvanus, National Museum of Rome

-

Antinous as Osiris

-

Head (the bust is modern), Antikensammlung Berlin

-

Egyptianizing statue of Antinoos, National Archaeological Museum of Athens

-

Antinous as Osiris, found in the ruins of Hadrian's villa during the 18th century

-

Sculpture of Antinous in the grounds of the New Palace, Potsdam.

Cultural references

Antinous remained a figure of cultural significance for centuries to come; as Vout noted, he was "arguably the most notorious pretty boy from the annals of classical history".[97] Sculptures of Antinous began to be reproduced from the sixteenth century; it remains likely that some of these modern examples have subsequently been sold as Classical artefacts and are still viewed as such.[98] Antinous has attracted attention from the gay subculture since the eighteenth century.[91]

Vout noted that Antinous came to be identified as "a gay icon".[99] Novelist and independent scholar Sarah Waters identified Antinous as being "at the forefront of the homosexual imagination" in late nineteenth-century Europe.[100] In this, Antinous replaced the figure of Ganymede, who had been the primary homoerotic representation in the visual arts during the Renaissance.[101] Gay author Karl Heinrich Ulrichs celebrated Antinous in an 1865 pamphlet that he authored under the pseudonym of "Numa Numantius."[101] In 1893, homophile newspaper The Artist, began offering cast statues of Antinous for £3, 10s.[101] The author Oscar Wilde referenced Antinous in both "The Young King" (1891) and "The Sphinx" (1894).[101]

At the time, Antinous' fame was increased by the work of fiction and writers and scholars, many of whom were not gay or lesbian.[102]

In Oscar Wilde's story "The Young King", a reference is made to the king kissing a statue of 'the Bithynian slave of Hadrian' in a passage describing the young king's aesthetic sensibilities and his "...strange passion for beauty...". Images of other classical paragons of male beauty, Adonis and Endymion, are also mentioned in the same context. Additionally, in Wilde's The Picture of Dorian Gray, the artist Basil Hallward describes the appearance of Dorian Gray as an event as important to his art as "the face of Antinous was to late Greek sculpture." Furthermore, in a novel attributed to Oscar Wilde, Teleny, or The Reverse of the Medal, Des Grieux makes a passing reference to Antinous as he describes how he felt during a musical performance. "...I now began to understand things hitherto so strange, the love the mighty monarch felt for his fair Grecian slave, Antinous, who-- like unto Christ-- died for his master's sake."[citation needed]

In "Les Miserables," the character Enjolras is likened to Antinous. "A charming young man who was capable of being a terror. He was angelically good-looking, an untamed Antinous.[103]" Hugo also remarks that Enjolras was 'seeming not to be aware of the existence on earth of a creature called woman."[104] In this way he can also be linked to an Antinoan ideal of male desire and beauty.

In "Klage Um Antinous," Der Neuen Gedichte, Anderer Teil (1908) by Rainer Maria Rilke,[105] Hadrian scolds the gods for Antinous's deification. "Lament for Antinoüs," translation by Stephen Cohn,[106]

In 1915 Fernando Pessoa wrote a long poem entitled Antinous, but he only published it in 1918, close to the end of World War I, in a slim volume of English verse. In 1921 he published a new version of this poem in English Poems, a book published by his own publishing house, Olisipo.

In Marguerite Yourcenar's Mémoires d'Hadrien (1951), the love relationship between Antinous and Hadrian is one of the main themes of the book.

A "sexually ambivalent" young man ('Murugan Mailendra') in Aldous Huxley's Island (1962) is likened to Antinous, and his lover Colonel Dipa (an older man) to Hadrian, after the narrator discovers the two are having a secret affair.

The story of Antinous' death was dramatized in the radio play "The Glass Ball Game", Episode Two of the second series of the BBC radio drama CAESAR, written by Mike Walker, directed by Jeremy Mortimer and starring Jonathan Coy as "Suetonius", Jonathan Hyde as "Hadrian" and Andrew Garfield as "Antinous". In this story, Suetonius is a witness to the events before and after Antinous's death by suicide, but learns that he himself was used as an instrument to trick Antinous into killing himself willingly to fulfill a pact made by Hadrian with Egyptian priests to give Hadrian more time to live so that Marcus Aurelius may grow up to become the next Emperor.

Antinous is seen walking with the other gods to war in Neil Gaiman's novel, "American Gods". In Tipping the Velvet (novel by Sarah Waters and its television adaptation), the lesbian protagonist Nan Astley dresses as Antinous for a costume party held by her partner.

References

Footnotes

- ^ The day and month of his birth come from an inscription on a tablet from Lanuvium dated 136 AD; the year is uncertain, but Antinous must have been about 18 when he drowned, the exact date of which event is itself not clear: certainly a few days before 30 Oct. 130 AD when Hadrian founded the city of Antinoöpolis, possibly on the 22nd (the Nile festival) or more likely the 24th (anniversary of the death of Osiris). See Lambert, p. 19, and elsewhere.

- ^ Birley 2000, p. 144.

- ^ Renberg, Gil H.: Hadrian and the Oracles of Antinous (SHA, Hadr. 14.7); with an appendix on the so-called Antinoeion at Hadrian’s Villa and Rome’s Monte Pincio Obelisk, Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome, Vol. 55 (2010) [2011], 159-198; Jones, Christopher P., New Heroes in Antiquity: From Achilles to Antinoos (Cambridge, Mass. & London, 2010), 75-83; Bendlin, Andreas: Associations, Funerals, Sociality, and Roman Law: The collegium of Diana and Antinous in Lanuvium (CIL 14.2112) Reconsidered, in M. Öhler (ed.), Aposteldekret und antikes Vereinswesen: Gemeinschaft und ihre Ordnung (WUNT 280; Tübingen, 2011), 207-296.

- ^ Vout 2007, p. 54.

- ^ Opper 1996, p. 170.

- ^ a b Lambert 1984, p. 48.

- ^ Lambert 1984, p. 15.

- ^ a b c Lambert 1984, p. 19.

- ^ Lambert 1984, pp. 20.

- ^ Lambert 1984, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Lambert 1984, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Lambert 1984, p. 22.

- ^ Lambert 1984, p. 60.

- ^ Lambert 1984, pp. 61–62.

- ^ a b c Lambert 1984, p. 63.

- ^ Lambert 1984, p. 97.

- ^ Lambert 1984, p. 30.

- ^ Lambert 1984, p. 39.

- ^ Lambert 1984, pp. 90–93.

- ^ Lambert 1984, p. 78.

- ^ Lambert 1984, pp. 81–83.

- ^ Lambert 1984, p. 65.

- ^ Lambert 1984, p. 94.

- ^ Lambert 1984, pp. 73–74.

- ^ a b c Lambert 1984, p. 71.

- ^ Lambert 1984, pp. 71–72.

- ^ Lambert 1984, pp. 100–106.

- ^ Lambert 1984, pp. 101–106.

- ^ Lambert 1984, pp. 110–114.

- ^ Lambert 1984, pp. 115–117.

- ^ a b Lambert 1984, pp. 118–121.

- ^ Lambert 1984, pp. 121, 126.

- ^ Lambert 1984, p. 126.

- ^ Lambert 1984, pp. 127–128.

- ^ Lambert 1984, p. 128.

- ^ Lambert 1984, p. 142; Vout 2007, p. 57.

- ^ Lambert 1984, p. 129.

- ^ Lambert 1984, p. 130.

- ^ Lambert 1984, p. 134.

- ^ Lambert 1984, pp. 130–141.

- ^ Lambert 1984, p. 143.

- ^ a b Lambert 1984, pp. 144–145.

- ^ Lambert 1984, pp. 146, 149.

- ^ Lambert 1984, pp. 146–147.

- ^ Lambert 1984, p. 177.

- ^ Lambert 1984, pp. 150–151.

- ^ Lambert 1984, p. 153.

- ^ Lambert 1984, p. 155.

- ^ Lambert 1984, pp. 158–160.

- ^ a b Lambert 1984, p. 149.

- ^ Lambert 1984, p. 148.

- ^ Lambert 1984, pp. 148, 163–164.

- ^ a b Lambert 1984, p. 165.

- ^ Lambert 1984, pp. 178–179.

- ^ Lambert 1984, p. 181–182.

- ^ Lambert 1984, p. 181.

- ^ Lambert 1984, p. 150.

- ^ Lambert 1984, p. 199.

- ^ Lambert 1984, pp. 200–202.

- ^ Lambert 1984, pp. 149, 205.

- ^ Lambert 1984, pp. 199–200, 205–206.

- ^ Lambert 1984, p. 206.

- ^ Lambert 1984, p. 198.

- ^ Lambert 1984, p. 207.

- ^ a b Lambert 1984, p. 152.

- ^ Lambert 1984, p. 162.

- ^ Lambert 1984, p. 180.

- ^ a b Lambert 1984, p. 184.

- ^ Lambert 1984, pp. 190–191.

- ^ Lambert 1984, pp. 177–178.

- ^ Lambert 1984, p. 192.

- ^ Lambert 1984, pp. 184–185.

- ^ a b c Lambert 1984, p. 186.

- ^ a b Vermeule 1979, p. 95.

- ^ Lambert 1984, pp. 189–190.

- ^ Lambert 1984, p. 188.

- ^ Lambert 1984, p. 189.

- ^ Lambert 1984, p. 194.

- ^ Lambert 1984, p. 187.

- ^ Lambert 1984, p. 195.

- ^ Lambert 1984, pp. 186–187.

- ^ a b Lambert 1984, pp. 192–193.

- ^ Pausanias, Description of Greece, 8.9.7 and 8.9.8

- ^ Lambert 1984, pp. 193–194.

- ^ a b Lambert 1984, p. 196.

- ^ Lambert 1984, pp. 195–196.

- ^ Wilson 1998, p. 440.

- ^ Vout 2007, p. 72.

- ^ Vout 2005, p. 83; Vout 2007, p. 87.

- ^ Vout 2007, pp. 77–78.

- ^ a b Waters 1995, p. 198.

- ^ a b Vout 2005, p. 82.

- ^ Lambert 1984, p. 80.

- ^ Lambert 1984, p. 209.

- ^ Mari, Zaccaria and Sgalambro, Sergio: "The Antinoeion of Hadrian's Villa: Interpretation and Architectural Reconstruction", American Journal of Archaeology, Vol 111, No 1, Jan. 2007,

- ^ Renberg, pp. 181-191.

- ^ Vout 2007, p. 52.

- ^ Vout 2005, pp. 83–84.

- ^ Vout 2007, p. 53.

- ^ Waters 1995, p. 194.

- ^ a b c d Waters 1995, p. 195.

- ^ Waters 1995, p. 196.

- ^ Hugo, Victor (1976). Les Misérables. Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England: Penguin Classics. p. 556. ISBN 978-0-14-044430-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Hugo, Victor (1976). Les Misérables. Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England: Penguin Classics Ltd. p. 557. ISBN 978-0-14-044430-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Der Neuen Gedichte. Gutenberg.org. Retrieved 2014-06-29.

- ^ Neue Gedichte - Rainer Maria Rilke - Google Books. Books.google.com. Retrieved 2014-06-29.

Bibliography

- Birley, A.R (2000). "Hadrian to the Antonines". In Alan K. Bowman; Peter Garnsey; Dominic Rathbone (eds.). The Cambridge ancient history: The High Empire, A.D. 70-192. Cambridge University Press.

- Lambert, Royston (1984). Beloved and God: The Story of Hadrian and Antinous. George Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Opper, Thorsten (1996). Hadrian: Empire and Conflict. Harvard University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Vermeule, Cornelius Clarkson (1979). Roman art: early Republic to late Empire. Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

- Vout, Caroline (2005). "Antinous, Archaeology, History". The Journal of Roman Studies. 95. Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies: 80–96. doi:10.3815/000000005784016342. JSTOR 20066818.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Vout, Caroline (2007). Power and Eroticism in Imperial Rome. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Waters, Sarah (1995). ""The Most Famous Fairy in History": Antinous and Homosexual Fantasy". Journal of the History of Sexuality. 6 (2). University of Texas Press: 194–230. JSTOR 3704122.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wilson, R.J.A (1998). "Roman art and architecture". In John Boardman (ed.). The Oxford history of the Roman world. Oxford University Press.

Further reading

- Grenier, L'Osiris Antinoos (2008) (online).

- John Addington Symonds, 'Antinous', in J. A. Symonds, Sketches And Studies In Italy (1879), p. 47-90

Ancient literary sources

- Biography of Hadrian in the Augustan History (attributed to Aelius Spartianus)

- Cassius Dio, epitome of book 69

External links

- The Temple of Antinous, Ecclesia Antinoi

- Antinous Homepage - various facets of the Antinous topic

- Cassius Dio's Roman History, epitome of Book 69

- Antinous: A poem by Fernando Pessoa. Lisbon: Monteiro, 1918.

- «Antinous» in English Poems I-II. Lisbon: Olisipo, 1921, pp. 5-16.

- Sculpture of Antinous[permanent dead link] at the Lady Lever Art Gallery

- Virtual Museum: Portraits of Antinous