Antonio Possevino

Antonio Possevino | |

|---|---|

Batory at Pskov. Painting by Jan Matejko. Possevino is the black-robed Jesuit at the center, blessing the offerings | |

| Born | Antonius Possevinus 10 July 1533 |

| Died | 26 February 1611 (aged 77) |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Occupation(s) | papal diplomat, Jesuit controversialist, encyclopedist and bibliographer |

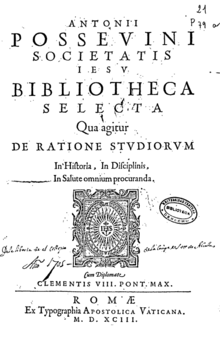

| Notable work | Bibliotheca selecta qua agitur de ratione studiorum (1593) Apparatus ad omnium gentium historiam (2 vols., 1597–1602) Apparatus sacer ad scriptores Veteris et Novi Testamenti (3 vols., 1603–06) |

Antonio Possevino (Antonius Possevinus) (10 July 1533 – 26 February 1611) was a Jesuit protagonist of Counter Reformation as a papal diplomat[1] and a Jesuit controversialist, polemicist, encyclopedist, and bibliographer.[2] He was the first Jesuit to visit Muscovy, Sweden, Denmark, Livonia, Hungary, Pomerania, and Saxony in amply documented papal missions between 1578 and 1586 where he championed the enterprising policies of Pope Gregory XIII.

Life

[edit]Mantua, Rome, and Ferrara: Renaissance humanist and tutor

[edit]Recent scholarship has identified Antonio Possevino's family as New Christians admitted to the learned circles of the court of Renaissance Mantua and its Gonzaga dukes. His father was Piedmontese from Asti and moved to Mantua where he joined the guild of goldsmiths. The family name was changed from Cagliano (Caliano) and had three sons, Giovanni Battista, Antonio and Giorgio.[3] His mother nursed her son Antonio in 1533 together with Francesco III Gonzaga, Duke of Mantua.[4]

His older brother, Giovanni Battista Possevino (1522–1552) arrived in the mid-1540s in the Rome of Paul III Farnese, first in the service of the Mantuan cardinal reformer Gregorio Cortese, then of the papal "cardinal nipote" Alessandro Farnese (cardinal) and finally of cardinal Ippolito II d'Este. In 1549 at seventeen Antonio came to study with his brother in Rome and met the leading intellectuals at the Renaissance court of pope Julius III (1550–1555), the patron of Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina and the builder of Villa Giulia. These included Fulvio Orsini and Paulus Manutius. In 1553 he published posthumously the Dialogo dell'Honore of Giovanni Battista who died not yet thirty. In Rome he dedicated the Centones ex Vergilio published under the name of Lelio Capilupi, to the French poet Joachim Du Bellay and in 1556 in Due Discorsi he defended his brother against accusations of plagiarism and defended the writings of Giovanni Battista Giraldi.

His brilliance and literary skills made the young humanist much in demand. When he left Rome he was engaged in service to Cardinal Ercole Gonzaga as tutor to the sons of his brother Ferrante Gonzaga, Francesco Gonzaga and Gian Vincenzo Gonzaga, both future cardinals. He moved with them to the literary capital of Italy, the city of Ferrara ruled by the House of Este. Possevino was connected with the Aristotelian revival associated with Francis Robortello and Vincenzo Maggi (1498–1564) that generated many treatises on literary and courtly matters including his brother's Dialogo dell'honore and his early works. When the University closed in Ferrara due to the Italian War of 1551–1559, Antonio moved to Padua. At this time Don Ferrante, his wards' father, died in the aftermath of the Battle of St. Quentin (1557). Possevino had become an expert in the historical training of princes and was writing commentaries on this battle exalting the victory of Emanuele Filiberto, Duke of Savoy. This produced a Piedmontese commendatore that he had to renounce in order to become a Jesuit, a severe hardship for his family, as his brother Giorgio was in jail and he was supporting his nephews, Giovanni Battista Bernardino Possevino and Antonio Possevino, both future translators and authors.

France and Savoy; Lyons: Counter Reformation Jesuit

[edit]But in Padua and in Naples he came in contact with the Society of Jesus and joined the order in 1559.[5] In 1560 Possevino was accompanied by Jesuit General Diego Lainez to the Savoy of Emanuele Filiberto where he bolstered the Catholic Church against heretics and he founded the Jesuit schools at Chambery, Mondovì and Turin.[6] In his efforts to bring the entrenched Waldensians around, he debated Scipione Lentolo (1525–1599), Calvin's emissary to the Italian Reformed community.[7] In combatting the influence of Calvin's Geneva increasingly he gravitated to France. This was at the onset of the Wars of Religion where he sought to rally the Catholics of Lyons together with Jesuit preacher Edmond Auger. He published a treatise on the Mass, Il sacrificio dell'altare (1563) and debated such Geneva reformers as Pierre Viret and the Italian Calvinist, Niccolo Balbani. For the Italian merchant community of Lyons he provided Catholic books, for example the Catechism of Peter Canisius and several other works in Italian. During this time he was put in jail and rescued from his Huguenot captors by influential adherents. In 1565 he successfully defended his order at the Colloquy at Bayonne before the boy king Charles IX and the future king Henri IV who remained a lifelong friend. In 1569 he wrote Il Soldato cristiano for pope Pius V who had it printed in Rome and distributed to the papal troops at the battle of Lepanto. He served as the rector of the Jesuit college of Avignon and then of Lyons where he received the Jesuit General Francis Borgia in 1571 on a journey from Spain to Rome.[8] He was there during the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre. During these militant years he first conceived of the plan of his Counter Reformation bibliographical works, as he states in the introduction to the Bibliotheca selecta.

Rome: Jesuit Secretary; Sweden, Poland, Russia: Apostolic Nuncio

[edit]When Borgia died, Possevino returned to Rome for the third Jesuit General Congregation and stayed on as the Latin secretary to Everard Mercurian, Jesuit general from 1572 until 1578. Pope Gregory XIII sent him to the court of King John III of Sweden in order to influence the course of the Livonian War. There King John converted to the Catholic Church and Possevino distributed the Holy Communion to him.[9] During this decade travelling around the Baltic and Eastern Europe Possevino wrote several tracts against his Protestant adversaries, including the Lutheran David Chytraeus, the Calvinist Andreas Volanus and the Unitarian Francis David[10] After Sweden and Poland Possevino proceeded to the Russian capital of Ivan the Terrible and helped to mediate between him and Stefan Bathory in the Treaty of Jam Zapolski in 1582. He left a valuable account of his nunciature in his description of the Tsardom of Muscovy. He also wrote accounts of his travels in Transylvania and Livonia. During these years he helped found, with Piotr Skarga, the Jesuit Vilnius University and Jesuit academies and seminaries in Braniewo, Olomouc and Cluj[11] historically connected to present day institutions. Possevino's efforts to bolster the Catholics in Poland under the patronage of Bathory engendered hostility to the Jesuit diplomat at the Habsburg court of Rudolf II reflected at the papal court of Rome.

Padua and Rome: Jesuit encyclopedist and bibliographer

[edit]After his protector Bathory's death at the end of 1586 Possevino was retired from diplomacy by Jesuit general Claudio Acquaviva. He was banned from Rome as too political and exiled to Venetian territory. In Padua Possevino continued to conduct the Ignatian Spiritual Exercises thus influencing the vocation of the Bishop and Saint Francis de Sales there as a student of law. Finally, in Padua began the scholarly project of assembling and organizing the library of orthodox Catholic learning assembled in the Bibliotheca selecta (1593) dedicated to Pope Clement VIII and Sigismund III Vasa. His sections were carefully reviewed by the leading professors of the Roman College including Christopher Clavius and Robert Bellarmine. Revisions and translations into Italian of books, which were originally included in the Bibliotheca Selecta, were later published as free standing works, such as the Coltura degl'Ingegni and Apparato All'Historia.[9][12] Next he set to preparing the compendious theological reference work Apparatus Sacer that brought him to Venice. During the 1590s while he was busy as a bibliographer he was also active in pastoral work in his native Mantua and at the court of Duke Vincenzo Gonzaga. Two missions on the status of the Jesuits in France brought him into renewed contact with recently converted Calvinist, King Henri IV.

Venice and Ferrara: Jesuit polemicist

[edit]During the production and publication of his enormous Apparatus Sacer (1603-06) in Venice, Possevino became the Jesuit leader of the traditionalist vecchi in opposing the anti-papal giovani who were being more successfully led by Servite historian Paolo Sarpi. There he fought the confessional "battle of the books" (la guerra delle scripture), during the Venetian Interdict, in a familiar diplomatic milieu that included the ambassador of James I, Sir Henry Wotton and the Venetian ambassador of his old acquaintance Henry IV of France.[13] Possevino's contributions to la guerra delle scritture was written under pseudonyms such as Giovanni Filoteo d'Asti, Teodoro Eugenio di Famagosta, and Paolo Anafesto.[9][14] In these texts, Possevino proves his loyality to the Roman Pontiff but not without acknowledging the glorious past of the Republic of Venice. Harsh words about Paolo Sarpi and the opposers of the legitimacy of the Interdict were expressed by Possevino, but, on the other hand, his adversaries did not hesitate to criticize him and other Jesuits.[9][15] Following the Interdict of Pope Paul V against Venice, Possevino was banished with the Society of Jesus from the Republic of Venice in 1606. He was sent to relative obscurity in nearby Ferrara where he wrote several polemical tracts under various pseudonyms concerning the pro-Catholic False Dmitriy I, the Venetian Interdict and other controversial issues.[16] Possevino's intention as a missionary, diplomat, and author was to promote a Catholic culture, which could outdo that of the Renaissance humanists. This culture was dependent on unity with the Roman Pontiff, as the prime spiritual and temporal authority.[9] Having outlived his role during the Counter Reformation as the political Jesuit intellectual, par excellence, he died in 1611.

Selected works

[edit]- Apparatus sacer ad scriptores Veteris et Novi Testamenti, also simply called Apparatus sacer, is one of the most celebrated works of Antonio Possevino (the other being Bibliotheca selecta). It is an overview of the different interpretations of the Old and New Testament by ecclesiastical authors from the Church fathers up to his contemporaries. It was printed in three volumes in Venice during the first decade of the 17th century. It references no less than six thousand authors.

- Bibliotheca selecta (Rome, 1593)([2])

- Del sacrificio dell'altare (Lyons, 1563) [English trans. Louvain, 1570]

- Risposta a Pietro Vireto, Nicolo Balbiani. e a due altri heretici (Avignon, 1566)

- Il soldato cristiano (Rome, 1569)

- Notæ verbi Dei et Apostolicæ Ecclesiæ (Posen, 1586)

- Muscovia (Vilna, 1586)([3])

- Iudicium de Nuae, Iohannis Bodini, Philippe-Mornaei et Machiavelli scriptis (Rome, 1592); (Lyons, 1593) ([4])

- Apparatus ad omnium gentium historiam (Venice, 1597)([5])

- Nuova risposta di Giovanni Filoteo d'Asti (Bologna, 1607)

- Risposta del Sig. Paolo Anafesto (Bologna, 1607)

Bibliography

[edit]- Alberto Castaldini (ed): Antonio Possevino; i gesuiti e la loro eredita culturale in Transilvania, Roma, IHSI, 2009, 188pp.

- Oxford Companion to the Book (2010), sub voce.

- E. García García and A. Miguel Alonso, “El Examen de Ingenios de Huarte de San Juan en la Bibliotheca Selecta de Antonio Possevino,” Revista de Historia la Psicología 24, no. 3–4 (2003): 387–96, http://www.revistahistoriapsicologia.es/archivo-all-issues/2003-vol-24-núm-3-4/.

- Paul Richard Blum, “Psychology and Culture of the Intellect: Ignatius of Loyola and Antonio Possevino,” in Cognitive Psychology in Early Jesuit Scholasticism, ed. Daniel Heider (Neunkirchen-Seelscheid: Editiones Scholasticae, 2016), 12–37.

- Antonio Possevino, Coltura degl’ingegni, ed. Cristiano Casalini and Luana Salvarani (Roma: Anicia, 2008).

- Paul Richard Blum, “Die geschmückte Judith: Die Finalisierung der Wissenschaften bei Antonio Possevino S.J.,” Nouvelles de la République des Lettres [no vol. no.] (1983): 113–26.

- Cristiano Casalini, “Disputa sugli ingegni. L’educazione dell’individuo in Huarte, Possevino, Persio e altri,” Educazione. Giornale di pedagogia critica 1 (2012): 29–51.

In literature

[edit]Possevino appears in the early chapters of Alison Macleod's historical novel "Prisoner of the Queen", in which he is the beloved and admired mentor of the protagonist.

References

[edit]- ^ Oresko, Robert; Gibbs, G. C.; Scott, Hamish M. (January 1997). Royal and Republican Sovereignty in Early Modern Europe: Essays in Memory of Ragnhild Hatton. Cambridge University Press. p. 667. ISBN 978-0-521-41910-9.

Possevino, Antonio, s.j., papal diplomat and visitor to Ivan IV's Muscovy

- ^ Luigi Balsamo, Antonio Possevino, Bibliografo della Controriforma (Florence, 2006)

- ^ Donnelly, John Patrick. Antonio Possevino and Jesuits of Jewish Ancestry in Archivum Historicum Societatis Iesu 109 (1986): 3-31.

- ^ Fumaroli, Marc. L'Age de l'Eloquence (Geneva, 1981), p. 163, "frere de lait". If this information is correct it should help clarify the birth year of Possevino as 1533, not 1533/ 1534, as many older sources cite.

- ^ La vocazione alla Compagnia di Gesu del p. Antonio Possevino in Archivum Historicum Societatis Iesu 12 (1945): 102-124. Possevino's Latin account of his vocation is in the Jesuit archives in Rome, Archivio Romano della Compagnia di Gesu, Hist. Soc. ff.183-195.

- ^ Mario Scaduto, S.J., Le missioni di Antonio Possevino in Piemonte: propaganda calvinistica e restaurazione cattolica, 1560-1563 Archivum Historicum Societatis Iesu 28 (1959): 51-191.

- ^ Joseph Visconti, The Waldensian Way to God (2003) p. 303. Also Camillo Crivelli La disputa di Antonio Possevino con i Valdesi (26 luglio 1560) in Archivum Historicum Societatis Iesu 7 (1938): 79-91.

- ^ Antonio Possevino in Diccionario Historico de la Compania de Jesus (Madrid, 2001) IV, 3202.

- ^ a b c d e Mazetti Petersson, Andreas (2022). A culture for the Christian commonwealth: Antonio Possevino, authority, history, and the Venetian Interdict. Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. ISBN 978-91-513-1553-9.

- ^ De sectariorum nostri temporis Atheismis liber (Vilna, 1586; Cologne, 1586)[1] This material reappears in Bibliotheca selecta Bk. 8.

- ^ Antonio Possevino. I gesuiti e la loro eredita culturale in Transilvania. Atti della Giornata di studio, Cluj-Napoca, 4 dicembre 2007. Edited by Alberto Castaldini. [Bibliotheca Instituti Historici Societatis Iesu, Vol. 67.] (Rome: Institutum Historicum Societatis Iesu. 2009

- ^ Mazetti Petersson, Andreas, ed. (2024-07-31). Antonio Possevino's Writings, vol. I: Apparato All'Historia (1598). Uppsala Studies in Church History ; 17 (in English and Italian). Uppsala, Sweden: Uppsala University, Department of Theology (published 2024-04-24). ISBN 978-91-985944-3-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ G. Sorano Il P. Antonio Possevino e l'ambasciatore inglese a Venezia (1604-1605) in Aevum 7 (1933): 385-422.

- ^ Mazetti Petersson, Andreas (2017). Antonio Possevino’s Nuova Risposta: Papal Power, Historiography and the Venetian Interdict Crisis, 1606–1607. Uppsala: Department of Theology, Uppsala University. ISBN 978-91-984129-3-2.

- ^ Mazetti Petersson, Andreas, ed. (2024-07-31). Antonio Possevino's Writings, vol II: Interdict Texts (1606-1607). Uppsala Studies in Church History ; 18 (in English and Italian). Uppsala: Uppsala University, Department of Theology (published 2024-04-27). ISBN 9789198594416.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ William J. Bouwsma, Venice and the Defense of Republican Liberty: Renaissance Values in the Age of the Counter Reformation (Berkeley, 1968) passim.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chambers, Ephraim, ed. (1728). Cyclopædia, or an Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (1st ed.). James and John Knapton, et al.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chambers, Ephraim, ed. (1728). Cyclopædia, or an Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (1st ed.). James and John Knapton, et al. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) [6]- Barbara Wolf-Dahm (1994). "Possevino, Antonio". In Bautz, Traugott (ed.). Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL) (in German). Vol. 7. Herzberg: Bautz. cols. 857–862. ISBN 3-88309-048-4.

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.