Augmented sixth chord

In music theory, an augmented sixth chord contains the interval of an augmented sixth, usually above its bass tone. This chord has its origins in the Renaissance,[1] further developed in the Baroque, and became a distinctive part of the musical style of the Classical and Romantic periods.[2] Conventionally used with a predominant function (resolving to the dominant), the three more common types of augmented sixth chords are usually called Italian sixth, French sixth, and German sixth.

Resolution and chord construction

The augmented sixth interval is typically between the sixth degree of the minor scale (henceforth ♭6) and the raised fourth degree (henceforth ♯4). With standard voice leading, the chord is followed directly or indirectly by some form of the dominant chord, in which both ♭6 and ♯4 have resolved to the fifth scale degree (henceforth 5). This tendency to resolve outwards to 5 is why the interval is spelled as an augmented sixth, rather than enharmonically as a minor seventh (♭6 and ♭5). Although augmented sixth chords are more common in the minor mode, they are also used in the major mode by borrowing ♭6 of the parallel minor scale.[3]

Double-diminished triad

In music theory, the double-diminished triad is an archaic concept and term referring to a triad, or three note chord, which, already being minor, has its root raised a semitone, making it doubly diminished. However, this may be used as the derivation of the augmented sixth chord.[4]

For example, F-A♭-C is a minor triad. F♯-A♭-C is a doubly diminished triad. Note that it is enharmonically equivalent to G♭-A♭-C (incomplete dominant seventh [missing E♭]), the tritone substitute resolving to G. Its inversion, A♭-C-F♯, is the Italian augmented sixth chord resolving to G.

Types

There are three main types of augmented sixth chords, commonly known as Italian sixth, French sixth, and German sixth. Though each is named after a European nationality, theorists disagree on their precise origins and have struggled for centuries to define their roots, and fit them into conventional harmonic theory.[3][5][6] According to Kosta & Payne, the other two terms are similar to the Italian sixth, which, "has no historical authenticity-[being] simply a convenient and traditional label."[7]

Italian sixth

The Italian sixth (It or It) is derived from iv with an altered fourth scale degree, ♯4: ♭6—1—♯4; A♭—C—F♯ in C major and C minor. This is the only augmented sixth chord comprising just three distinct notes; in four-part writing, the tonic pitch is doubled.

The Italian sixth is enharmonically equivalent to an incomplete dominant seventh.[8]

French sixth

The French sixth (Fr or Fr) is similar to the Italian, but with an additional tone, 2: ♭6—1—2—♯4; A♭—C—D—F♯ in C major and C minor. The notes of the French sixth chord are all contained within the same whole tone scale, lending a sonority common to French music in the 19th century (especially associated with Impressionist music).[9]

German sixth

The German sixth (Gr or Ger) is also like the Italian, but with an added tone ♭3: ♭6—1—♭3—♯4; A♭—C—E♭—F♯ in C major and C minor. In Classical music, however, it appears in much the same places as the other variants, though perhaps less used because of the contrapuntal difficulties outlined below. It appears frequently in the works of Beethoven,[a] and in ragtime music.[10] The German sixth chord contains the same notes as a dominant seventh chord (enharmonically ♯4 is ♭5), though it functions differently.

It is more difficult to avoid parallel fifths when resolving a German sixth chord to the dominant, V. These parallel fifths, referred to as Mozart fifths, were occasionally accepted by common practice composers. There are two ways they can be avoided:

- The ♭3 can move to either 1 or 2, thereby generating an Italian or French sixth, respectively, and eliminating the perfect fifth between ♭6 and ♭3.[11]

- The chord can resolve to a "six-four" chord, functionally either as a cadential six-four intensification of V, or as the second inversion of I; the cadential six-four, in turn, resolves to a root-position V. This progression ensures that, in its voice leading, each pair of voices moves either by oblique motion or contrary motion and avoids parallel motion altogether. In minor modes, both 1 and ♭3 do not move during the resolution of the German sixth to the cadential six-four. In major modes, ♭3 can be enharmonically respelled as ♯2 if it resolves upwards to ♮3, similar in voice leading to the resolution of French sixth to the cadential six-four. This respelled chord is sometimes referred to as the English, Swiss or Alsatian sixth chord,[citation needed] or as a "'doubly augmented sixth chord"',[citation needed] as it contains two augmented intervals. However, other sources describe it as a German sixth, such as Grove.[12]

Listen)

Listen)Other variants

Other variants of augmented sixth chords can be found in the repertoire, and are sometimes given whimsical geographical names. For example: 4—♭6—7—♯2; (F—A♭—B—D♯) is called by one source an Australian sixth.[13] Such anomalies usually have alternative interpretations.

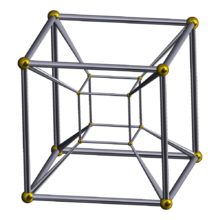

Relationship between the various types of augmented 6th chords

The following "curious chromatic sequence",[14] graphed in Tymoczko (2011) as a 4-dimensional tesseract,[15] outlines the relationships between the augmented sixth chords in 12TET tuning:

- Starting with a diminished seventh chord, lower any factor by semitone. The result is equivalently a German sixth chord.

- From the German sixth chord, lower any factor by semitone so that the result is ancohemitonic (i.e.: possesses no halfsteps). The result is a French sixth chord or minor seventh chord possibly posing as augmented 6th.

- From the French sixth chord or minor seventh chord possibly posing as augmented 6th, there exists a factor which, when lowered by semitone, gives a result equivalently a half-diminished seventh chord possibly posing as augmented 6th.

- From the half-diminished seventh chord possibly posing as augmented 6th, there exists a factor which, when lowered by semitone, gives a result equivalently a diminished seventh chord at the interval 1 semitone lower than the diminished seventh chord which started the sequence.

- Three repetitions of the above complete the cycle in modulo-12 note space, forming a necklace of three tesseracts joined at opposite corners by diminished seventh chords and subsuming all 12 notes of the chromatic scale.

Half-diminished seventh as virtual +6 chord

The half-diminished seventh chord is the involution of the German augmented sixth chord.[16] Its interval of minor seventh (between root and seventh degree, i.e.: { C B♭ } in { C E♭ G♭ B♭ } ) can be written as an augmented sixth { C E♭ G♭ A♯ }.[17] Rearranging and transposing, this gives { A♭ C♭ D F♯ }, a virtual minor version of the French augmented sixth chord.[18][need quotation to verify] Like the typical +6, this enharmonic interpretation gives on a resolution irregular for the half-diminished seventh but normal for the augmented sixth, where the 2 voices at the enharmonic major second converge to unison or diverge to octave.[19]

Minor seventh as virtual +6 chord

The minor seventh chord may also have its interval of minor seventh (between root and seventh degree, i.e.: { C B♭ } in { C E♭ G B♭ } ) rewritten as an augmented sixth { C E♭ G A♯ }.[17] Rearranging and transposing, this gives { A♭ C♭ E♭ F♯ }, a virtual minor version of the German augmented sixth chord.[20] Again like the typical +6, this enharmonic interpretation gives on a resolution irregular for the minor seventh but normal for the augmented sixth, where the 2 voices at the enharmonic major second converge to unison or diverge to octave.[19]

Standard harmonic function

One way to emphasize a tone is to approach it by a half step, either from above or from below. ... Approaching the dominant by half steps from above and below at the same time makes for an even stronger approach to the dominant... The two approaching tones form a vertical interval of an augmented 6th. This method of approaching the dominant distinguishes a whole category of chords called augmented sixth chords.[21]

From the Baroque to the Romantic period, augmented sixth chords have had the same harmonic function: as a chromatically altered predominant chord (typically, an alteration of ii, IV, vi7 or their parallel equivalents in the minor mode) leading to a dominant chord. This movement to the dominant is heightened by the semitonal resolution of both ♭6 to 5 and ♯4 to 5; essentially, these two notes act as leading-tones. This characteristic has led many analysts[22] to compare the voice leading of augmented sixth chords to the secondary dominant V of V because of the presence of ♯4, the leading-tone of V, in both chords. In the major mode, the chromatic voice leading is more pronounced because of the presence of two chromatically altered notes, ♭6, as well as ♯4, rather than just ♯4 in the minor mode.

In most occasions, the augmented-sixth chords precede either the dominant, or the tonic in second inversion.[8] The augmented sixths can be treated as chromatically altered passing chords.[8]

Root position and inversion of augmented sixth chords

Augmented sixth chords are occasionally used with a different chord member in the bass. Since there is no consensus among theorists that they are in root position in their normal form, the word "inversion" isn't necessarily accurate, but is found in some textbooks, nonetheless. Sometimes, "inverted" augmented sixth chords occur as a product of voice leading.

Rousseau considered that the chord could not be inverted.[23] 17th century instances of the augmented sixth with the sharp note in the bass are generally limited to German sources.[24]

Simon Sechter explains the chord of the French Sixth as being a chromatically altered version of a seventh chord on the second degree of the scale. The German Sixth is explained as a chromatically altered ninth chord on the same root, but with the root omitted.[25]

The tendency of the interval of the augmented sixth to resolve outwards is therefore explained by the fact that the A♭, being a dissonant note, a diminished fifth above the root (D), and flatted, must fall, whilst the F♯ – being chromatically raised – must rise.

Extended functions

In the late Romantic period and other musical traditions, especially jazz, other harmonic possibilities of augmented sixth variants and sonorities outside its function as a predominant were explored, exploiting their particular properties. An example of this is through the "reinterpretation" of the harmonic function of a chord: Since a chord could simultaneously have more than one enharmonic spelling with different functions (i.e., both predominant as a German sixth and dominant as a dominant seventh), its function could be reinterpreted mid-phrase. This heightens both chromaticism by making possible the tonicization of remote keys, and possible dissonances with the juxtaposition of remotely related keys.

Augmented sixth chords as altered dominant chords with flattened 2nd degree

The augmented sixth chord may be built on notes other than ♭6.

Tchaikovsky considered the augmented sixth chords as being altered dominants.[26] He described the augmented sixth chords as inversions of the diminished triad and of dominant and diminished seventh chords with the second degree chromatically lowered, and accordingly resolving into the tonic. He notes that, "some theorists insist upon [augmented sixth chord's] resolution not into the tonic but into the dominant triad, and regard them as being erected not on the altered 2-nd degree, but on the altered 6-th degree in major and on the natural 6-th degree in minor", yet calls this view, "fallacious", insisting that a, "chord of the augmented sixth on the 6-th degree is nothing else than a modulatory degression into the key of the dominant".[27]

Classical harmonic theory would notate the "tritone substitute" as an augmented sixth chord on ♭2. The Augmented sixth chord can either be the It+6 enharmonic to a dominant 7th chord without the 5th, Gr+6, enharmonically equivalent to a dominant 7th chord with the 5th, or Fr+6 enharmonically equivalent to the Lydian dominant without the 5th, all of which serve in a classical context as a substitute for the secondary dominant of V.[28][29]

Enharmonicity to other chords

Enharmonic equivalency of the French sixth

This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2014) |

The French sixth has two characteristics in common with the diminished seventh chord:

- Both chords are constructed of two superimposed tritones; in the French sixth, between ♭6—2 (A♭—D) and 1—♯4 (C—F♯). Thus, both have inversional symmetry;

- Both are enharmonically equivalent at the tritone; i.e., both chords transposed up or down a tritone will result in the same pitches as the original.

As with the diminished seventh chord, the latter property allows the chord to be used in modulating to very remote keys. For instance: ♭6—1—2—♯4; (A♭—C—D—F♯ in C), could be interpreted identically in F♯ if reordered and respelled as D—F♯—G♯—B♯, i.e., the French sixth of the ♯IV key area, displaced an interval of a tritone relative to the tonic key, I.

Dominant functions

|

|

All variants of augmented sixth chords are closely related to the applied dominant V7 of ♭II; both Italian and German variants are enharmonically identical to dominant seventh chords. For example, in the key of C (I), the German sixth chord, A♭—C—E♭—F♯, could be reinterpreted as A♭—C—E♭—G♭, the applied dominant of D♭ (V/D♭).

Tristan chord

Richard Wagner's Tristan chord (indicated below with Fr) from the opening of his opera, Tristan und Isolde, can be interpreted as a half-diminished seventh that transitions to a French sixth in the key of A minor (F-A-B-D♯). The upper voice continues upward with a long appoggiatura (G♯ to A). Note that the D♯ resolves downwards to D♮ instead of E:

This may be a result of eliding the downward resolution in order to make another French sixth (E-G♯-A♯-D) which incidentally shares three notes with the dominant of the excerpt.[original research?]

See also

Notes

- ^ Notable examples include the themes of the slow movements (both in variation form) of the opp. 57 ("Appassionata") and 109 piano sonatas.

References

- ^ Andrews, Herbert Kennedy (1950). The Oxford Harmony. Vol. 2 (1 ed.). London: Oxford University Press. pp. 45–46. OCLC 223256512.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - ^ Andrews 1950, pp. 46–52

- ^ a b Aldwell, Edward; Schachter, Carl (1989). Harmony and Voice Leading (2 ed.). San Diego, Toronto: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. pp. 478–483. ISBN 0-15-531519-6. OCLC 19029983.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - ^ Ernst Friedrich Richter (1912). Manual of Harmony, p.94. Theodore Baker.

- ^ Gauldin, Robert (1997). Harmonic Practice in Tonal Music (1 ed.). New York: W.W. Norton. pp. 422–438. ISBN 0-393-97074-4. OCLC 34966355.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - ^ Christ, William (1973). Materials and Structure of Music. Vol. 2 (2 ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. pp. 141–171. ISBN 0-13-560342-0. OCLC 257117.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) Offers a detailed explanation of augmented sixth chords as well as Neapolitan sixth chords. - ^ Kostka & Payne (1995), p.385.

- ^ a b c Rimsky, p. 121.

- ^ Blatter, Alfred (2007). Revisiting Music Theory: a Guide to the Practice, p.144. ISBN 978-0-415-97440-0. "One may note that the French sixth contains the elements of a whole tone scale commonly associated with French impressionistic composers."

- ^ a b Benward, Bruce and Saker, Marilyn (2009). Music in Theory and Practice, Vol. II, p.105. Eighth edition. McGraw Hill. ISBN 9780073101880.

- ^ Benjamin, Thomas; Horvit, Michael; Nelson, Robert (2008). Techniques and Materials of Music: From the Common Practice Period Through the Twentieth Century (7 ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson & Schirmer. p. 165. ISBN 978-0-495-18977-0. OCLC 145143714.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) Beethoven frequently moves from one form of the chord to another in such a way, sometimes passing through all three. - ^ Drabkin, William. Augmented sixth chord. Grove Music Online (subscription needed). Accessed March 2012.

- ^ Burnard, Alex (1950). Harmony and Composition: For the Student and the Potential Composer. Melbourne: Allans Music (Australia). pp. 94–95. OCLC 220305086.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - ^ Ouseley, Frederick. A. Gore (1868). A Treatise on Harmony, pg. 138, Oxford, Clarendon Press.

- ^ Tymoczko, Dimitri (2011). A Geometry of Music: Harmony and Counterpoint in the Extended Common Practice, pg. 106, Oxford: Oxford University.

- ^ Hanson, Howard. (1960) Harmonic Materials of Modern Music, p.356ff. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts. LOC 58-8138.

- ^ a b Ouseley, Frederick. A. Gore (1868). A Treatise on Harmony, pg. 137, Oxford, Clarendon Press.

- ^ Chadwick, G. W. (1922). Harmony: A Course of Study, pg. 138ff, Boston, B. F. Wood. [ISBN unspecified]

- ^ a b Christ, William (1966). Materials and Structure of Music, v.2, p. 154. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall. LOC 66-14354.

- ^ Ouseley (1868), pg. 143ff.

- ^ Kostka, Stefan and Payne, Dorothy (1995). Tonal Harmony, p.384. 3rd edition. McGraw Hill. ISBN 0070358745.

- ^ Piston, Walter; Mark DeVoto (1987). Harmony (5 ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. p. 419. ISBN 0-393-95480-3.

- ^ Rousseau, Jean Jaques. Dictionnaire de Musique.

- ^ Ellis, Mark (2010). A Chord in Time: The Evolution of the Augmented Sixth from Monteverdi to Mahler, pp. 92–94. Farnham: Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-7546-6385-0.

- ^ a b Sechter, Simon (1853). Die Grundsätze der musicalischen Komposition (in German). Leipzig: Breitkopf und Härtel.

- ^ Roberts, Peter Deane (1993). Modernism in Russian Piano Music: Skriabin, Prokofiev, and Their Russian Contemporaries, p.136. ISBN 0-253-34992-3.

- ^ a b Tschaikovsky, Peter (1900). "XXVII". In Translated from the German version by Emil Krall and James Liebling (ed.). Guide to the Practica Study of Harmony (English translation ed.). Leipzig: P. Jurgenson. pp. 106, 108.

- ^ Satyendra, Ramon. "Analyzing the Unity within Contrast: Chick Corea's Starlight", p.55. Cited in Stein.

- ^ Stein, Deborah (2005). Engaging Music: Essays in Music Analysis. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-517010-5.

- ^ Benward & Saker (2008). Music in Theory and Practice, Vol. II, p.222. ISBN 978-0-07-310188-0. Original: G♭, B♭, C♯, E to F♯, A♯, C♯, E.

- ^ Owen, Harold (2000). Music Theory Resource Book, p.132. ISBN 0-19-511539-2.

- ^ Benward, Bruce, and Marilyn Nadine Saker (2008). Music in Theory and Practice, vol. 2, p.233. Boston: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-310188-0.

Books

- Rimsky-Korsakov, Nikolai (1886). Practical Treatise on Harmony (13th – 1924 ed.). St. Petersburg: A. Büttner.

- Piston, Walter (1941). Harmony (co-author Mark DeVoto 5th – 1987 ed.). New York and London: W. W. Norton & Company.