Baghdad Battery

The Baghdad Battery or Parthian Battery is a set of three artifacts which were found together: a ceramic pot, a tube of one metal, and a rod of another. The current interpretation[citation needed] of their purpose is as a storage vessel for sacred scrolls such as those from nearby Seleucia on the Tigris. Although the Seleucia vessels do not have the outermost clay jar, they are otherwise almost identical.[2][a]

Wilhelm König was a professional painter[citation needed] who was an assistant at the National Museum of Iraq in the 1930s. In 1938 he authored a paper[3] offering the hypothesis that they may have formed a galvanic cell, perhaps used for electroplating gold onto silver objects.[2][4] This interpretation is generally rejected today.[5][6]

While some researchers refer to the object as a battery, the origin and purpose of the object remains unclear.[7] In March 2012, Professor Elizabeth Stone, of Stony Brook University, an expert on Iraqi archaeology, returning from the first archaeological expedition in Iraq after 20 years, stated that she does not know a single archaeologist who believed that these were batteries.[8][9]

Physical description

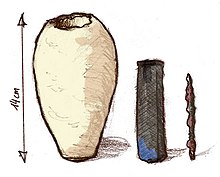

The artifacts consist of terracotta pots approximately 130 mm (5 in) tall (with a one-and-a-half-inch mouth) containing a cylinder made of a rolled copper sheet, which houses a single iron rod. At the top, the iron rod is isolated from the copper by bitumen, which plugs or stoppers, and both rod and cylinder fit snugly inside the opening of the jar. The copper cylinder is not watertight, so if the jar were filled with a liquid, this would surround the iron rod as well. The artifact had been exposed to the weather and had suffered corrosion.

König thought the objects might date to the Parthian period, between 250 BC and AD 224, but according to St John Simpson of the Near Eastern department of the British Museum, their original excavation and context were not well-recorded, and evidence for this date range is very weak. Furthermore, the style of the pottery is Sassanid (224-640).[2][10]

Most of the components of the objects are not particularly amenable to advanced dating methods. The ceramic pots could be analysed by thermoluminescence dating, but this has not yet been done; in any case, it would only date the firing of the pots, which is not necessarily that of the complete artifact.

Theories concerning operation

Some believe that wine, lemon juice, grape juice, or vinegar was used as an acidic electrolyte solution to generate an electric current from the difference between the electrode potentials of the copper and iron electrodes.[2][10]

König had observed a number of very fine silver objects from ancient Iraq, plated with very thin layers of gold, and speculated that they were electroplated using batteries with these as the cells.

Supporting experiments

After the Second World War, a man named Willard Gray demonstrated current production by a reconstruction of the inferred battery design when filled with grape juice.[4] W. Jansen experimented with benzoquinone (some beetles produce quinones) and vinegar in a cell and got satisfactory performance.[4]

In 1978, Arne Eggebrecht reportedly reproduced the electroplating of gold onto a small statue. There are no (direct) written or photographic records of this experiment. [b] The only records are segments of a television show.

Controversies over use

Battery hypothesis

The artifacts do not form a useful voltaic for several reasons:[original research?]

- Gas is evolved at an iron/copper/electrolyte junction. Bubbles form a partial insulation of the electrode. Thus the more the battery is used, the less well it works.

- Although several volts can be produced by connecting batteries in series, the voltage generated by iron/copper/electrolyte junctions is below 1 volt[citation needed].

Electroplating hypothesis

König himself seems to have been mistaken on the nature of the objects he thought were electroplated. They were apparently fire-gilded (with mercury). Paul Craddock of the British Museum said "The examples we see from this region and era are conventional gold plating and mercury gilding. There’s never been any irrefutable evidence to support the electroplating theory".[2]

David A. Scott, senior scientist at the Getty Conservation Institute and head of its Museum Research Laboratory, wrote that "There is a natural tendency for writers dealing with chemical technology to envisage these unique ancient objects of two thousand years ago as electroplating accessories (Foley 1977). but this is clearly untenable, for there is absolutely no evidence for electroplating in this region at the time."[11]

Paul T. Keyser of the University of Alberta noted that Eggebrecht used a more efficient, modern electrolyte, and that using only vinegar, or other electrolytes available at the time assumed, the battery would be very feeble, and for that and other reasons concludes that even if this was in fact a battery, it could not have been used for electroplating. However, Keyser still supported the battery theory, but believed it was used for some kind of mild electrotherapy such as pain relief, possibly through electroacupuncture.[10][12]

Bitumen as an insulator

A bitumen seal, being thermoplastic, would be extremely inconvenient for a galvanic cell, which would require frequent topping up of the electrolyte (if they were intended for extended use).[5][13][14]

Alternative hypothesis

The artifacts strongly resemble another type of object with a known purpose – storage vessels for sacred scrolls from nearby Seleucia on the Tigris.[15] Those vessels do not have the outermost clay jar, but are otherwise almost identical. Since these vessels were exposed to the elements,[2][c][improper synthesis?] it is possible that any papyrus or parchment inside had completely rotted away, perhaps leaving a trace of slightly acidic organic residue.[16] Likewise the thermoplastic bitumen makes an excellent hermetic seal for long-term storage.[citation needed]

In the media

The idea that the terracotta jars in certain circumstances could have been used to produce usable levels of electricity has been put to the test at least twice. On the 1980 British Television series Arthur C. Clarke's Mysterious World, Egyptologist Arne Eggebrecht created a voltaic cell using a jar filled with grape juice, to produce half a volt of electricity, demonstrating for the programme that jars used this way could electroplate a silver statuette in two hours, using a gold cyanide solution. Eggebrecht speculated that museums could contain many items mislabelled as gold when they are merely electroplated.[17]

The Discovery Channel program MythBusters built replicas of the jars to see if it was indeed possible for them to have been used for electroplating or electrostimulation. On MythBusters' 29th episode (March 23, 2005), ten hand-made terracotta jars were fitted to act as batteries. Lemon juice was chosen as the electrolyte to activate the electrochemical reaction between the copper and iron. Connected in series, the batteries produced 4 volts of electricity. When linked in series the cells had sufficient power to electroplate a small token.[18]

Archaeologist Ken Feder commented on the show noting that no archaeological evidence has been found either for connections between the jars (which were necessary to produce the required voltage) or for their use for electroplating.[19] In fact, plating of the era in which the batteries are claimed to have been used, have been found to be fire-gilded (with mercury).[2]

In 2016, a team of researchers from Vanderbilt University developed a low-cost rechargeable "junkyard battery" using scrap steel and brass, by converting the surface of these metals into iron oxide and copper oxide nano structured architectures using an anodization process. The team drew inspiration from the simple design of the Baghdad battery.[20][21]

See also

- Dendera light

- Coso artifact – misinterpreted by some to be a 500,000-year-old spark plug

- History of the battery

- List of topics characterized as pseudoscience

References

- ^ Arran Frood's BBC article: "The artifact had been exposed to the weather and had suffered corrosion, although mild given the presence of an electrochemical couple.

- ^ In Arran Frood's BBC article: "There does not exist any written documentation of the experiments which took place here in 1978," says Dr Bettina Schmitz, currently a researcher based at the same Roemer and Pelizaeus Museum. "The experiments weren't even documented by photos, which really is a pity," she says. "I have searched through the archives of this museum and I talked to everyone involved in 1978 with no results."

- ^ Arran Frood's BBC article: "The artifact had been exposed to the weather and had suffered corrosion, although mild given the presence of an electrochemical couple.

- ^ "Paranormal Image Gallery – Ancient Mysteries/Aztec carving of ancient astronaut". Unexplained Mysteries. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved November 14, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g Frood, Arran (February 27, 2003). "Riddle of 'Baghdad's batteries'". BBC News. Archived from the original on April 6, 2012. Retrieved April 6, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^

- W. König, "Ein galvanisches Element aus der Partherzeit?", Forschungen und Fortschritte, vol. 14 (1938), pp. 8-9.

- W. König, Im Verlorenen Paradies-Neun Jahre Irak, pp. 166-68, Munich and Vienna: 1939.

- ^ a b c The Baghdad Battery, Museum of Unnatural Mystery website.

- ^ a b Baghdad batteries on the Bad Archaeology Network website.

- ^ "Erich von Däniken's Chariots of the Gods: Science or Charlatanism?", Robert Sheaffer. First published in the "NICAP UFO Investigator", October/November, 1974.

- ^ Frood, A. Riddle of 'Baghdad's batteries' BBC News 27 February, 2003

- ^ Stone, Elizabeth (March 23, 2012). "Archaeologists Revisit Iraq". Science Friday (Interview). Interviewed by Flatow, Ira. Retrieved April 6, 2012.

My recollection of it is that most people don't think it was a battery. ...It resembled other clay vessels... used for rituals, in terms of having multiple mouths to it. I think it's not a battery. I think the people who argue it's a battery are not scientists, basically. I don't know anybody who thinks it's a real battery in the field.

- ^ Prof. Stone's statement, listed as a 'red flag' among 5 red flags why it was not a battery (with sources, on Archaeology Fantasies website)

- ^ a b c Paul T. Keyser, "The Purpose of the Parthian Galvanic Cells: A First-Century A. D. Electric Battery Used for Analgesia", Journal of Near Eastern Studies, vol. 52, no. 2, pp. 81-98, April 1993. Includes images of the artifact and similar objects.

- ^ Scott, David A. (2002). Publications Copper and Bronze in Art: Corrosion, Colorants, Conservation. pp. 16–18. ISBN 978-0-89236-638-5.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Oxford University, Elizabeth Frood editor (on eScholarship website): Eggebrecht's account

- ^ the Baghdad Battery on The Iron Skeptic website

- ^ "The Baghdad Battery – and Ancient Electricity". Michigan State University students website, citing the now offline SkepticWorld.com website and viewpoint. October 12, 2010. Archived from the original on November 9, 2013. Retrieved March 9, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The batteries of Babylon: evidence for ancient electricity?". Bad Archaeology.

- ^ "The Baghdad Battery: An Update". Daily Kos.

- ^ Welfare, S. and Fairley, J. Arthur C. Clarke's Mysterious World (Collins 1980), pp. 62–64.

- ^ Ancient batteries episode on Mythbusters.

- ^ "Ancient Alien Astronauts: Interview with Ken Feder". Monster Talk Podcast. July 27, 2011. Retrieved June 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Muralidharan, Nitin; Westover, Andrew S. "From the Junkyard to the Power Grid: Ambient Processing of Scrap Metals into Nanostructured Electrodes for Ultrafast Rechargeable Batteries". ACS Energy Letters. doi:10.1021/acsenergylett.6b00295.

- ^ "Making high-performance batteries from junkyard scraps".