Bahrain Grand Prix

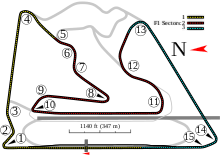

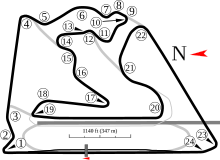

| Bahrain International Circuit (2004–2010, 2012–present) | |

| |

| Race information | |

|---|---|

| Number of times held | 20 |

| First held | 2004 |

| Most wins (drivers) | |

| Most wins (constructors) | |

| Circuit length | 5.412 km (3.363 miles) |

| Race length | 308.238 km (191.530 miles) |

| Laps | 57 |

| Last race (2024) | |

| Pole position | |

| Podium | |

| |

| Fastest lap | |

The Bahrain Grand Prix (Arabic: جائزة البحرين الكبرى), officially known as the Gulf Air Bahrain Grand Prix for sponsorship reasons, is a Formula One motor racing event in Bahrain.[1] The first race took place at the Bahrain International Circuit on 4 April 2004. It made history as the first Formula One Grand Prix to be held in the Middle East, and was given the award for the "Best Organised Grand Prix" by the FIA.[2] The race has in the past been the second, third, or fourth race of the Formula One calendar. However, in the 2006 season, Bahrain swapped places with the traditional season opener, the Australian Grand Prix, which was pushed back to avoid a clash with the Commonwealth Games. Bahrain staged the opening race of the 2010 season and the cars drove the full 6.299 km (3.914 mi) "Endurance Circuit" to celebrate F1's 'diamond jubilee'. In 2021, the Bahrain Grand Prix was the season opener again because the 2021 Australian Grand Prix was cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The 2011 edition, due to be held on 13 March, was cancelled on 21 February due to the 2011 Bahraini protests[3] after drivers including Damon Hill and Mark Webber had protested.[4] Human rights activists called for a cancellation of the 2012 race due to reports of human rights abuses committed by the Bahraini authorities.[5] Team personnel also voiced concerns about safety,[6] but the race, nonetheless, was held as planned on 22 April 2012.

In 2014, to commemorate the tenth anniversary of the first staging of the Bahrain Grand Prix, the race was held as a night event under floodlights.[7] In so doing it became the second Formula One night race after the Singapore Grand Prix in 2008. Bahrain's inaugural night event was won by Lewis Hamilton. Subsequent races have also been night races.

History

[edit]

The construction of the Bahrain International Circuit in Sakhir began in 2002. Bahrain had fought off fierce competition from elsewhere in the region to stage a F1 race, with Egypt, Lebanon and the United Arab Emirates all hoping for the prestige of hosting a Formula One Grand Prix.

The race has been held in every Formula One season since 2004, with the exception of 2011, due to the 2011 Bahraini uprising. The first Bahrain Grand Prix was won by Michael Schumacher, driving for Ferrari. The following two editions, in 2005 and 2006, were won by Fernando Alonso, racing for Renault, and Felipe Massa won the 2007 and 2008 editions of the race for Ferrari. Jenson Button won the 2009 Bahrain Grand Prix driving for Brawn GP, and Fernando Alonso won his third Bahrain Grand Prix in 2010 driving for Ferrari. Following the cancellation of the 2011 Bahrain Grand Prix, Sebastian Vettel and Red Bull won the 2012 and 2013 Grands Prix, followed by Lewis Hamilton and Mercedes winning in 2014 and 2015. Hamilton's teammate Nico Rosberg won in 2016, and Sebastian Vettel won another two editions of the race for Ferrari in 2017 and 2018. Lewis Hamilton then proceeded to win the following three Grands Prix, in 2019, 2020, and 2021, setting the record for the most Bahrain Grand Prix wins, with five. The 2022 round was won by Charles Leclerc, giving the Scuderia Ferrari their record seventh Bahrain Grand Prix victory. The most recent edition, held in 2024, was won by Max Verstappen of Red Bull Racing, with the previous year's event their first Bahrain Grand Prix victory in over ten years.[8][9]

The 2010 edition of the race saw a different circuit configuration used for the Grand Prix. The "Endurance Circuit" layout was used instead of the "Grand Prix Circuit" layout, extending the lap length to 6.299 km (3.914 mi).[10] The track was planned to revert back to its original layout for the 2011 edition,[11] and did so for the 2012 edition.[12]

In February 2022, it was reported that the event's contract had been extended to last until the 2036 Formula One season.[13]

Characteristics

[edit]One notable characteristic of the course is its large run-off areas, which have been criticised for not punishing drivers who stray off the track. However, they tend to prevent sand getting onto the track. The circuit is regarded as one of the safest in the world.[14]

Although alcoholic beverages are legal in Bahrain, the drivers do not spray the traditional champagne on the podium, instead spraying a non-alcoholic rosewater drink known as Waard.[14]

Controversy

[edit]2011 cancellation

[edit]

On 21 February 2011, it was announced that the 2011 Bahrain Grand Prix scheduled for 13 March was cancelled due to the 2011 Bahraini protests.[3][15] On 3 June, FIA decided to reschedule the race for 30 October. World champion racer Damon Hill called on Formula One not to reschedule saying that if the race went ahead "we will forever have the blight of association with repressive methods to achieve order".[16] Bernie Ecclestone told the BBC in an interview: "Hopefully there'll be peace and quiet and we can return in the future, but of course it's not on. The schedule cannot be rescheduled without the agreement of the participants – they're the facts."[17] A week after its decision to reschedule the race, Formula One announced the cancellation of the race for 2011.[4]

2012 controversy

[edit]

Human rights activists called for a cancellation of the 2012 Bahrain Grand Prix, which took place on 22 April, because of reports of ongoing use of excessive force by authorities and torture in detention.[5][18][19] That includes the killing of activist Salah Abbas Habib during a demonstration on the eve of the Grand Prix,[20] as well as the earlier fatal shooting of photojournalist Ahmed Ismael Hassan al-Samadi, who was covering a protest against the Bahrain Grand Prix.[21]

On 9 April 2012, The Guardian reported that according to an unnamed leading member of one of the teams who said his views were representative, "the Formula One teams want the sport's governing body to cancel – or at least postpone – the Bahrain Grand Prix ..., because of increasing safety concerns amid ongoing protests in the kingdom ... I feel very uncomfortable about going to Bahrain. If I'm brutally frank, the only way they can pull this race off without incident is to have a complete military lockdown there. And I think that would be unacceptable, both for F1 and for Bahrain. But I don't see any other way they can do it".[6]

In that context, Anonymous launched on 21 April 2012 the operation opBahrain, threatening the Formula 1 representatives of a cyberattack in case they go on with the Grand Prix. Hours later, Anonymous hackers took down the f1-racers.net website after launching a distributed denial-of-service attack.[22] Despite these protests, the Grand Prix was held as planned.

Continuing controversy

[edit]Since the global media attention over the large scale demonstrations in 2011 and 2012, there have been continued reports from human rights groups about abuses and jailings in Bahrain relating to F1 protests. Among them are photographer Ahmed Humaidan, who was one of about 30 people jailed for roles in the 2012 protest,[23] and activist Najah Ahmed Yousif, who is in prison, and has been physically and sexually abused, for criticising the Bahrain F1 on social media.[24][25] Rights organisations continue to criticise the Formula One Group and Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile (FIA) for refusing to follow their own Statement of Commitment to Respect for Human Rights, saying that by not leveraging their position of power to take action against such political crackdown, the F1 organisers are complicit to the dissidents' suffering.[26] In 2018, F1 "admitted concern" for Yousif, after continued public and media pressure; however, there has been no known follow up since.[27]

A collection of human rights groups, led by the Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy (BIRD), have claimed that the Bahrain Grand Prix has become a focal point of popular protests and serious human rights abuses committed by Bahraini security forces against protesters. The NGOs accuse F1 of performing invaluable PR for Bahrain's government and that it risked further normalizing of the human rights violations in the country.[28] In letters to Lewis Hamilton, three Bahraini political prisoners praised his commitment towards human rights issues, and requested him as an F1 world champion to bring their plight in notice of a wider audience.[29] The Grand Prix has been cited as an example of sportswashing.[30]

2020 postponement

[edit]Responding to the COVID-19 pandemic, event organisers announced that no spectators would be permitted to attend the race that had been due to take place on 22 March.[31] However, a fortnight before the race was due to take place, the race was indefinitely postponed.[32] The race was rescheduled to 29 November, and it was one of two events held around the Bahrain International Circuit across two weekends, with the second race taking place on the outer layout and being named the Sakhir Grand Prix.

2020 controversy

[edit]According to the rescheduled F1 calendar, Bahrain was announced as hosting two races back to back November 2020. However, the event received backlash not only from human rights organizations, but also from F1's newly crowned, seven-time world champion Lewis Hamilton. Hamilton issued a warning to F1 and called on the sport to face its responsibilities and confront / deal with the human rights issues in the countries it visits. A consortium of human rights organizations led by the Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy (BIRD) wrote to Formula One CEO, Chase Carey that the race in Bahrain became a focal point of protests in the country and human rights abuses carried out by Bahraini security against demonstrators. The government of Bahrain, on the other hand, denied allegations of sportswashing.[33]

Legal complaint over Bahrain contract

[edit]On 27 October 2022, the F1 was hit with a legal complaint that it turned a blind eye to human rights violations when it announced in February that the Bahrain GP will stay on the calendar until 2036. The claim said F1 breached Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development guidelines. The complaint, made through the British government’s UK National Contact Point (NCP), was served by the Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy (Bird) and two alleged torture survivors from Bahrain, Najah Yusuf and Hajer Mansoor.[34]

Winners

[edit]Repeat winners (drivers)

[edit]Drivers in bold are competing in the Formula One championship in the current season.

| Wins | Driver | Years won |

|---|---|---|

| 5 | 2014, 2015, 2019, 2020, 2021 | |

| 4 | 2012, 2013, 2017, 2018 | |

| 3 | 2005, 2006, 2010 | |

| 2 | 2007, 2008 | |

| 2023, 2024 | ||

| Source:[9] | ||

Repeat winners (constructors)

[edit]Teams in bold are competing in the Formula One championship in the current season.

| Wins | Constructor | Years won |

|---|---|---|

| 7 | 2004, 2007, 2008, 2010, 2017, 2018, 2022 | |

| 6 | 2014, 2015, 2016, 2019, 2020, 2021 | |

| 4 | 2012, 2013, 2023, 2024 | |

| 2 | 2005, 2006 | |

| Source:[9] | ||

Repeat winners (engine manufacturers)

[edit]Manufacturers in bold are competing in the Formula One championship in the current season.

| Wins | Manufacturer | Years won |

|---|---|---|

| 7 | 2004, 2007, 2008, 2010, 2017, 2018, 2022 | |

| 2009, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2019, 2020, 2021 | ||

| 4 | 2005, 2006, 2012, 2013 | |

| 2 | 2023, 2024 | |

| Source:[9] | ||

By year

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Grandprix.com. "Gulf Air to sponsor Bahrain Grand Prix". www.grandprix.com. Archived from the original on 18 October 2021. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- ^ Huda Al Shamlan (29 March 2012). "Formula One Comes Back". Bahrain News Agency. Archived from the original on 8 April 2018. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ a b "Bahrain Grand Prix called off due to protests" Archived 25 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine, bbc.co.uk, 21 February 2011. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ^ a b "Bahrain's Crash Course; Formula One drivers for democracy" Archived 9 April 2018 at the Wayback Machine, 9 June 2011, The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ a b Lubbock, John; Rajab, Nabeel (30 January 2012). "Bahrain has failed to grasp reform – so why is the Grand Prix going ahead?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 25 August 2014. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ a b Weaver, Paul; Black, Ian (9 April 2012). "Formula One 2012. F1 teams want FIA to postpone Bahrain Grand Prix". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 27 November 2020. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ Benson, Andrew (29 November 2013). "Bahrain F1 Grand Prix to become night race in 2014". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 29 November 2013. Retrieved 30 November 2013.

- ^ a b "Sakhir" (in French). StatsF1. Archived from the original on 5 December 2019. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ a b c d e "Bahrain GP". ChicaneF1. Archived from the original on 3 September 2021. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ Noble, Jonathan (25 January 2010). "Bahrain unveils new layout for F1 race". autosport.com. Haymarket Publications. Archived from the original on 28 January 2010. Retrieved 25 January 2010.

- ^ "Sakhir reverts to old layout for 2011 Bahrain Grand Prix". En.espnf1.com. 16 August 2010. Archived from the original on 20 December 2013. Retrieved 5 March 2012.

- ^ "Race Preview: 2012 Bahrain Grand Prix 20–22 April 2012". FIA. Archived from the original on 23 April 2012. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ "Bahrain Grand Prix to remain in F1 until 2036". ESPN.com. 11 February 2022. Archived from the original on 11 February 2022. Retrieved 11 February 2022.

- ^ a b "Bahrain Grand Prix: in pictures". The Daily Telegraph. 2011. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ Baldwin, Alan (3 June 2011). "Motor racing-Bahrain GP to go ahead this year – circuit chairman". Reuters. Archived from the original on 27 April 2015. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ^ Cary, Tom (2 June 2011). "Damon Hill calls on Bernie Ecclestone and Formula One to abandon Bahrain Grand Prix". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022.

- ^ "Bahrain GP cannot go ahead – Bernie Ecclestone". En.espnf1.com. 8 June 2011. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 5 March 2012.

- ^ "Ecclestone insists on Bahrain GP despite human rights abuses". Al-Akhbar English. 12 April 2012. Archived from the original on 27 April 2015. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ "Bahrain: Grand Prix Decision Ignores Abuses. F1 Should Consider Rights Implications of Scheduled Race". Human Rights Watch. 14 April 2012. Archived from the original on 18 April 2012. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ Adetunji, Jo; Beaumont, Peter; agencies (21 April 2012). "Bahrain protester found dead on eve of grand prix". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 28 March 2019. Retrieved 29 March 2019 – via www.theguardian.com.

- ^ "Journalist Ahmed Ismael Hassan al-Samadi Dies as Bahrain Violence Continues". International Business Times. 2 April 2012. Archived from the original on 28 March 2019. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- ^ Protalinski, Emil (21 April 2012). "Anonymous hacks Formula 1". ZDNet. Archived from the original on 24 April 2012. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- ^ Avenue, Committee to Protect Journalists 330 7th; York, 11th Floor New; Ny 10001 (26 March 2014). "Freelance Bahraini photographer given 10-year prison term". cpj.org. Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Sexually Assaulted Bahraini Female Activist Sentenced to Three Years in Prison over Facebook Comments Criticizing Formula One Race in Bahrain". birdbh.org. 25 June 2018. Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- ^ Yusuf, Najah (27 March 2019). "Every moment I spend in prison in Bahrain stains the reputation of F1 – Najah Yusuf". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 29 March 2019 – via www.theguardian.com.

- ^ "Bahrain: FIA Urged to Visit F1 Political Prisoners in Jail". birdbh.org. 27 March 2019. Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- ^ Ingle, Exclusive by Sean (14 November 2018). "F1 finally admits concern over woman jailed for Bahrain Grand Prix protests". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 29 March 2019 – via www.theguardian.com.

- ^ Richards, Giles (25 November 2020). "Formula One faces charge of aiding sportwashing by racing in Bahrain". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 25 November 2020. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ Richards, Giles (25 November 2020). "Bahraini political prisoners appeal to Lewis Hamilton for his help". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 25 November 2020. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ Richards, Giles (25 November 2020). "Formula One faces charge of aiding sportwashing by racing in Bahrain". Guardian.com. Archived from the original on 26 November 2020. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- ^ Chapman, Simon (8 March 2020). "No spectators for Bahrain Grand Prix". Speedcafe. Archived from the original on 1 March 2021. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- ^ "Bahrain and Vietnam Grands Prix postponed". www.formula1.com. 13 March 2020. Archived from the original on 15 March 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- ^ Richards, Giles (25 November 2020). "Formula One faces charge of aiding sportwashing by racing in Bahrain". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 25 November 2020. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ Richards, Giles (27 October 2022). "F1 faces legal challenge over Bahrain contract and sportswashing". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 27 October 2022. Retrieved 27 October 2022.