Baron Munchausen

| Baron Munchausen | |

|---|---|

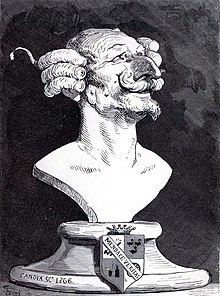

Gustave Doré's portrait of Baron Munchausen | |

| First appearance | Baron Munchausen's Narrative of his Marvellous Travels and Campaigns in Russia (1785) |

| Created by | Rudolf Erich Raspe |

| Portrayed by | |

| Voiced by |

|

| Based on | Hieronymus Karl Friedrich von Münchhausen (1720–1797) |

| In-universe information | |

| Nickname | Lügenbaron ("Baron of Lies") |

| Title | Baron |

| Nationality | German |

Baron Munchausen (Template:Lang-de)[a] is a fictional German nobleman in literature and film, loosely based on a real baron, Hieronymus Karl Friedrich, Freiherr von Münchhausen (German pronunciation: [ˈmʏnç(h)aʊzən]; 11 May 1720 – 22 February 1797).

The real-life Münchhausen became a minor celebrity for telling outrageous tall tales based on his military service in the Russo-Turkish War. After hearing some of Münchhausen's stories, the writer Rudolf Erich Raspe adapted them into an anonymously published English-language volume about a fictional "Baron Munchausen." The book was subsequently translated back into German and expanded by the poet Gottfried August Bürger. The real-life Münchhausen was deeply upset at the development of a fictional character bearing his name.

Raspe's book was a major international success, and versions of the fictional Baron have appeared on stage, screen, radio, and television. In addition, three medical conditions (Munchausen syndrome, Munchausen syndrome by proxy, and Munchausen by Internet) and a logical problem (the Münchhausen Trilemma) are named after the character.

Historical figure

Hieronymus von Münchhausen | |

|---|---|

Münchhausen c. 1740 as a Cuirassier in Riga, by G. Bruckner | |

| Born | Hieronymus Karl Friedrich von Münchhausen 11 May 1720 |

| Died | 22 February 1797 (aged 76) |

| Nationality | |

| Occupation(s) | Nobleman Military officer |

| Known for | Tall tales |

| Spouse(s) | Jacobine von Dunten Bernardine von Brunn |

Hieronymus Karl Friedrich von Münchhausen was born in Bodenwerder, Electorate of Brunswick-Lüneburg, into an aristocratic family of the Hanover region.[3] His father's second cousin, de, was prime minister under George III of Great Britain.[citation needed] Münchhausen started as a page to Anthony Ulrich II of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, and followed his employer to the Russian Empire during the Russo-Turkish War (1735–1739).[3] In 1739, he was appointed a cornet in the Russian cavalry regiment, the "Brunswick-Cuirassiers". The following year, he was promoted to lieutenant. He was stationed in Riga, but participated in two campaigns against the Turks in 1740 and 1741. In 1744 he married Jacobine von Dunten, and in 1750 he was promoted to Rittmeister, a cavalry captain.[3]

In 1760 Münchhausen retired to live as a Freiherr at his estates in Bodenwerder, where he remained until his death in 1797.[3][4] It was there, especially at parties given for the area's aristocrats, that he developed a reputation as an imaginative after-dinner storyteller, creating witty and highly exaggerated accounts of his adventures in Russia. Over the ensuing thirty years, his storytelling abilities gained such renown that he frequently received visits from traveling nobles wanting to hear his stories.[5] However, Münchhausen was considered an honest man in business affairs, rather than a liar.[3] As one contemporary put it, Münchhausen's unbelievable narratives were designed not to deceive, but "to ridicule the disposition for the marvellous which he observed in some of his acquaintances."[6]

Münchhausen married a second time, to Bernardine von Brunn, in 1794, which ended in divorce. He did not have any children.[3]

Fictionalization

The fictionalized character was created by a German-born writer, scientist, and con artist, Rudolf Erich Raspe.[7] Raspe, while living at Göttingen, was introduced to Münchhausen and sometimes invited to dine with him at the mansion at Bodenwerder.[7] Raspe's later career mixed writing and scientific scholarship with theft and swindling; when the German police issued advertisements for his arrest in 1775, he fled continental Europe and settled in England.[8]

In his native German language, Raspe wrote a collection of anecdotes based on Münchhausen's tales, calling the collection "M-h-s-nsche Geschichten" ("M-h-s-n Stories"). It appeared as a feature in the eighth issue of the Vade mecum für lustige Leute (Handbook for Fun-loving People), a Berlin humor magazine, in 1781. Raspe published a sequel, "Noch zwei M-Lügen" ("Two more M-Fibs"), in the tenth issue of the same magazine in 1783.[9] The hero and narrator of these stories was identified only as "M-h-s-n," keeping Raspe's inspiration partly obscured while still allowing knowledgeable German readers to make the connection to Münchhausen.[10] Raspe's name did not appear at all.[9]

Then, in 1785, while supervising mines at Dolcoath in Cornwall, he wrote a short English-language book based on Münchhausen's stories, identifying the narrator of the book as "Baron Munchausen."[11] It remains unclear how much of Raspe's material comes directly from the Baron, but the majority of the stories are derived from older sources,[12] including Heinrich Bebel's Facetiæ (1508) and Samuel Gotthold Lange's Deliciæ Academicæ (1765).[13] Other than the anglicization of Münchhausen to "Munchausen," Raspe this time made no attempt to hide the identity of the man who had inspired him, though he still withheld his own name.[14]

Raspe's text had a circuitous publication history. It first appeared anonymously as Baron Munchausen's Narrative of his Marvellous Travels and Campaigns in Russia, a forty-nine-page book in 12mo size, published in Oxford by the bookseller Smith in late 1785 and sold for a shilling.[15] A second edition early the following year, retitled Singular Travels, Campaigns, Voyages, and Sporting Adventures of Baron Munnikhouson, commonly pronounced Munchausen, added five additional stories and four illustrations; though the book was still anonymous, the new text was probably by Raspe, and the illustrations may have been his work as well.[16]

By May 1786, however, Raspe no longer had control over the book, which was taken over by a different publisher, G. Kearsley.[17][b] Kearsley, intending the book for a higher-class audience than the original editions had been, commissioned extensive additions and revisions from other hands, including new stories, twelve new engravings, and much rewriting of Raspe's prose. This third edition was sold at two shillings, twice the price of the original, as Gulliver Revived, or the Singular Travels, Campaigns, Voyages, and Adventures of Baron Munikhouson, commonly pronounced Munchausen.[18]

Raspe's English version of the Munchausen stories became the core text for almost all later versions.[19] Translations into French and Spanish were published in 1786.[14] At least ten editions or translations appeared before Raspe's death in 1794.[20]

Gottfried August Bürger, a German Romantic poet, may have written the preface for the 1785 edition of Raspe's book.[13] In 1785, Bürger translated the fourth edition of the book into German, with his own additions.[13] He published it under the title of Wunderbare Reisen zu Wasser und zu Lande: Feldzüge und lustige Abenteuer des Freiherrn von Münchhausen ("Marvellous Travels on Water and Land: Campaigns and Comical Adventures of the Baron of Münchhausen").[21]

Raspe, for unknown reasons, never admitted his authorship of the book.[20] It was often credited to Bürger,[13] sometimes with an accompanying rumor that the real-life Baron von Münchhausen had met Bürger in Pyrmont and dictated the entire work to him.[22] Another rumor, which circulated widely soon after the book was published, claimed that the book was a competitive collaboration by three Göttingen University scholars—Bürger, Abraham Gotthelf Kästner, and Georg Christoph Lichtenberg—with each of the three trying to outdo one other by writing the most unbelievable tale.[23] The scholar de correctly credited Raspe for the core text, but mistakenly asserted that Raspe had written it in German and that an anonymous translator was responsible for the English version.[22] Raspe's authorship was finally proven in 1824 by Bürger's biographer, de.[24] Because of the complicated history of additions, some nineteenth-century editions of the work are credited simply to "R. E. Raspe and Others."[14]

In the first few years after publication, however, German readers widely assumed that the real-life Baron von Münchhausen was responsible for the stories. According to witnesses, Münchhausen was deeply angry that the book had dragged his name into public consciousness and insulted his honor as a nobleman. Münchhausen became a recluse, refusing to host parties or tell any more stories,[14] and he attempted without success to bring legal proceedings against Bürger and the publisher of the translation.[25]

| Publication history of Raspe's English text | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Edition | Title on title page | Publication | Contents |

| First | Baron Munchausen's Narrative of his Marvellous Travels and Campaigns in Russia. Humbly dedicated and recommended to Country Gentlemen; and, if they please, to be repeated as their own, after a Hunt, at Horse Races, in Watering Places, and other such polite Assemblies, round the bottle and fireside | Oxford: Smith, 1786 [actually late 1785][c] | Adaptations by Raspe of fifteen of the sixteen anecdotes from "M-h-s-nsche Geschichten" and both of the anecdotes from "Noch zwei M-Lügen." |

| Second | Singular Travels, Campaigns, Voyages, and Sporting Adventures of Baron Munnikhouson, commonly pronounced Munchausen; as he relates them over a Bottle when surrounded by his Friends. A New Edition, considerably enlarged, and ornamented with four Views, engraved from the Baron's own drawings | Oxford: Smith, [April] 1786 | Same as the First Edition, plus five new stories probably by Raspe and four illustrations possibly also by Raspe. |

| Third | Gulliver Revived, or the singular Travels, Campaigns, Voyages, and Adventures of Baron Munikhouson, commonly pronounced Munchausen. The Third Edition, considerably enlarged, and ornamented with Views, engraved from the original designs | Oxford: G. Kearsley, [May] 1786 | Same stories and engravings as the Second Edition, plus new non-Raspe material and twelve new engravings. Many alterations are made to Raspe's original text. |

| Fourth | Gulliver Revived containing singular Travels, Campaigns, Voyages, and Adventures in Russia, Iceland, Turkey, Egypt, Gibraltar, up the Mediterranean, and on the Atlantic Ocean: Also an Account of a Voyage into the Moon, with many extraordinary Particulars relative to the Cooking Animal in that Planet, which are here called the Human Species, by Baron Munchausen. The Fourth Edition. Considerably enlarged, and ornamented with Sixteen explanatory Views, engraved from Original Designs | London: G. Kearsley, [July] 1786 | Same stories as the Third Edition, plus new material not by Raspe, including the cannonball ride, the journey with Captain Hamilton, and the Baron's second trip to the Moon. Additional alterations to Raspe's text. Eighteen engravings, though only sixteen are mentioned on the title page. |

| Fifth | Gulliver Revived, containing singular Travels, Campaigns, Voyages, and Adventures in Russia, the Caspian Sea, Iceland, Turkey, Egypt, Gibraltar, up the Mediterranean, on the Atlantic Ocean and through the Centre of Mount Etna into the South Sea: Also an Account of a Voyage to the Moon and Dog Star, with many extraordinary Particulars relative to the Cooking Animal in those Planets, which are here called the Human Species, by Baron Munchausen. The Fifth Edition, considerably enlarged, and ornamented with a variety of explanatory Views, engraved from Original Designs | London: G. Kearsley, 1787 | Same contents as the Fourth Edition, plus the trips to Ceylon (added at the beginning) and Mount Etna (at the end), and a new frontispiece. |

| Sixth | Gulliver Revived or the Vice of Lying properly exposed; containing singular Travels, Campaigns, Voyages, and Adventures in Russia, the Caspian Sea, Iceland, Turkey, Egypt, Gibraltar, up the Mediterranean, on the Atlantic Ocean and through the Centre of Mount Etna into the South Sea: also an Account of a Voyage into the Moon and Dog-Star with many extraordinary Particulars relative to the Cooking Animal in those Planets, which are there called the Human Species by Baron Munchausen. The Sixth Edition. Considerably enlarged and ornamented with a variety of explanatory Views engraved from Original Designs | London: G. Kearsley, 1789[d] | Same contents as the Fifth Edition, plus a "Supplement" about a ride on an eagle and a new frontispiece. |

| Seventh | The Seventh Edition, Considerably enlarged, and ornamented with Twenty Explanatory Engravings, from Original Designs. Gulliver Revived: or, the Vice of Lying properly exposed. Containing singular Travels, Campaigns, Voyages, and Adventures in Russia, the Caspian Sea, Iceland, Turkey, Egypt, Gibraltar, up the Mediterranean, on the Atlantic Ocean and through the Centre of Mount Aetna, into the South Sea. Also, An Account of a Voyage into the Moon and Dog-Star; with many extraordinary Particulars relative to the Cooking Animal in those Planets, which are there called the Human Species. By Baron Munchausen | London: C. and G. Kearsley, 1793 | Same as the Sixth Edition. |

| Eighth | The Eighth Edition, Considerably enlarged, and ornamented with Twenty Explanatory Engravings, from Original Designs. Gulliver Revived: or, the Vice of Lying properly exposed. Containing singular Travels, Campaigns, Voyages, and Adventures in Russia, the Caspian Sea, Iceland, Turkey, Egypt, Gibraltar, up the Mediterranean, on the Atlantic Ocean and through the Centre of Mount Aetna, into the South Sea. Also, An Account of a Voyage into the Moon and Dog-Star; with many extraordinary Particulars relative to the Cooking Animal in those Planets, which are there called the Human Species. By Baron Munchausen | London: C. and G. Kearsley, 1799 | Same as the Sixth Edition. |

| Unless otherwise referenced, information in this table comes from the Munchausen bibliography established by John Carswell.[28] | |||

| List of early Munchausen translations and sequels | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Language | Title | Publication | Contents |

| German | Wunderbare Reisen zu Wasser und Lande, feldzüge und lustige Abentheuer des Freyherrn von Münchhausen wie er dieselben bey der Flasche im Zirkel seiner Freunde zu Erzählen pflegt. Aus dem Englischen nach der neuesten Ausgabe übersetzt, hier und da erweitert und mit noch mehr Küpfern gezieret | London [actually Göttingen]: [Johann Christian Dieterich,] 1786 | Gottfried August Bürger's free translation of the English Third Edition, plus new material added by Bürger. Four illustrations from the English Third Edition and three new ones. |

| French | Gulliver ressuscité, ou les voyages, campagnes et aventures extraordinaires du Baron de Munikhouson | Paris: Royez, 1787 | Slightly modified translation of the English Fifth Edition. |

| German | Wunderbare Reisen zu Wasser und Lande, feldzüge und lustige Abentheuer des Freyherrn von Münchhausen, wie er dieselben bey der Flasche im Zirkel seiner Freunde zu Erzählen pflegt. Aus dem Englischen nach der neuesten Ausgabe übersetzt, hier und da erweitert und mit noch mehr Küpfern gezieret. Zweite vermehrte Ausgabe | London [actually Göttingen]: [Johann Christian Dieterich,] 1788 | Same as previous German edition, plus a translation of the new material from the English Fifth Edition, greatly revised. |

| German | Nachtrag zu den wunderbaren Reisen zu Wasser und Lande, und lustige Abentheuer des Freyherrn von Münchhausen, wie er dieselben bey der Flasch Wein im Zirkel seiner Freunde selbst zu erzählen pflegt. Mit Küpferrn | Copenhagen, 1789 | Original German sequel, sharply satirizing the Baron. Includes twenty-three engravings and an "Elegy on the Death of Herr von Münchhausen" (though the real-life Baron had not yet died). |

| English | A Sequel to the Adventures of Baron Munchausen humbly dedicated to Mr Bruce the Abyssinian Traveller, As the Baron conceives that it may be of some service to him making another expedition into Abyssinia; but if this does not delight Mr Bruce, the Baron is willing to fight him on any terms he pleases | [London:] H. D. Symonds, 1792 [a second edition was published 1796] | Original English sequel, satirizing Robert Bruce. Includes twenty engravings. This Sequel was often printed alongside the Raspe text as "Volume Two of the Baron's Travels." |

| Unless otherwise referenced, information in this table comes from the Munchausen bibliography established by John Carswell.[28] | |||

Fictional character

The fictional Baron Munchausen is a braggart soldier, most strongly defined by his comically overexaggerated boasts about his own adventures;[29] all of the stories in Raspe's book are told in first-person narrative, with a prefatory note explaining that "the Baron is supposed to relate these extraordinary Adventures over his Bottle, when surrounded by his Friends."[30] The Baron's stories imply him to be a superhuman figure who spends most of his time either getting out of absurd predicaments or indulging in equally absurd moments of gentle mischief.[31] In some of his most well-known stories, the Baron rides a cannonball, travels to the Moon, is swallowed by a giant fish in the Mediterranean Sea, saves himself from drowning by pulling on his own hair, fights a forty-foot crocodile, enlists a wolf to pull his sleigh, and uses laurel tree branches to fix his horse when the animal is accidentally cut in two.[13]

In the stories he narrates, the Baron is shown as a calm, rational man, describing what he experiences with simple objectivity; absurd happenings elicit, at most, mild surprise from him, and he shows serious doubt about any unlikely events he has not witnessed himself.[32] The resulting narrative effect is an ironic tone, encouraging skepticism in the reader[33] and marked by a running undercurrent of subtle social satire.[31] In addition to his fearlessness when hunting and fighting, he is suggested to be a debonair, polite gentleman given to moments of gallantry, with a scholarly penchant for knowledge, a tendency to be pedantically accurate about details in his stories, and a deep appreciation for food and drink of all kinds.[34]

Because the feats the Baron describes are overtly implausible, they are easily recognizable as fiction,[35] with a strong implication that the Baron is a liar.[29] Whether he expects his audience to believe him varies from version to version; in Raspe's original 1785 text, he simply narrates his stories without further comment, but in the 1792 extended version, he is insistent that he is telling the truth.[36] In any case, the Baron appears to believe every word of his own stories, no matter how internally inconsistent they become, and he usually appears tolerantly indifferent to any disbelief he encounters in others.[37]

Illustrators of the Baron stories have included Thomas Rowlandson, Alfred Crowquill, George Cruikshank, de, Theodor Hosemann, Adolf Schrödter, Gustave Doré, William Strang,[38] and W. Heath Robinson.[39] In the first published illustrations, which may have been drawn by Raspe himself, the Baron appears slim and youthful.[40] For the 1792 edition, an anonymous artist drew the Baron as a dignified but tired old soldier whose face is marred by injuries from his adventures; this illustration remained the standard portrait of the Baron for about seventy years, and its imagery was echoed in Cruikshank's depictions of the character. Doré, illustrating the Théophile Gautier translation in 1862, retained the sharply beaked nose and twirled moustache from the 1792 portrait, but gave the Baron a healthier and more affable appearance; the Doré Baron became the definitive visual representation for the character.[41]

The relationship between the real and fictional Barons is a complex one. On the one hand, the fictional Baron Munchausen can be easily distinguished from the historical figure Hieronymus von Münchhausen;[2] the character is so separate from his namesake that at least one critic, the writer W. L. George, concluded that the namesake's identity was irrelevant to the general reader,[42] and Richard Asher named Munchausen syndrome using the anglicized spelling so that the disorder would reference the character rather than the real person.[2] On the other hand, Münchhausen remains strongly connected to the character he inspired, and is still nicknamed the Lügenbaron ("Baron of Lies") in German.[14] As the Munchausen researcher Bernhard Wiebel has said, "These two barons are the same and they are not the same."[43]

Critical and popular reception

Reviewing the first edition of Raspe's book in December 1785, a writer in The Critical Review commented appreciatively:[44]

This is a satirical production calculated to throw ridicule on the bold assertions of some parliamentary declaimers. If rant may be best foiled at its own weapons, the author's design is not ill-founded; for the marvellous has never been carried to a more whimsical and ludicrous extent.[44][e]

A writer for The English Review was less approving: "We do not understand how a collection of lies can be called a satire on lying, any more than the adventures of a woman of pleasure can be called a satire on fornication."[45]

W. L. George described the fictional Baron as a "comic giant" of literature, describing his boasts as "splendid, purposeless lie[s] born of the joy of life."[46] Thomas Seccombe commented that "Munchausen has undoubtedly achieved [a permanent place in literature] … The Baron's notoriety is universal, his character proverbial, and his name as familiar as that of Mr. Lemuel Gulliver, or Robinson Crusoe."[47] Théophile Gautier highlighted that the Baron's adventures are endowed with an "absurd logic pushed to the extreme and which backs away from nothing."[48]

Steven T. Byington wrote that "Munchausen's modest seat in the Valhalla of classic literature is undisputed," comparing the stories to American tall tales and concluding that the Baron is "the patriarch, the perfect model, the fadeless fragrant flower, of liberty from accuracy."[49] In a 2012 study of the Baron, the academician Sarah Tindal Kareem noted that "Munchausen embodies, in his deadpan presentation of absurdities, the novelty of fictionality [and] the sophistication of aesthetic illusion," adding that the additions to Raspe's text made in 1792 and onward tend to mask these ironic literary qualities by overemphasizing that the Baron is lying.[36]

During the nineteenth century, Raspe's book was widely popular, especially with young readers.[50] Robert Southey referred to Raspe's text as "a book which everybody knows, because all boys read it."[51] Similarly, Robert Chambers, in an 1863 almanac, cited the iconic 1792 illustration of the Baron by asking rhetorically:

Who is there that has not, in his youth, enjoyed The Surprising Travels and Adventures of Baron Munchausen in Russia, the Caspian Sea, Iceland, Turkey, &c. a slim volume—all too short, indeed—illustrated by a formidable portrait of the baron in front, with his broad-sword laid over his shoulder, and several deep gashes on his manly countenance? I presume they must be few.[50]

By the 1850s, "Munchausen" had come into slang use as a verb meaning "to tell extravagantly untruthful pseudo-autobiographical stories."[52]

In addition to the many augmented and adapted editions of Raspe's text, the fictional Baron has occasionally appeared in other standalone works.[53] In the late nineteenth century, the Baron appeared as a character in John Kendrick Bangs's comic novels A House-Boat on the Styx, Pursuit of the House-Boat, and The Enchanted Type-Writer.[54] Shortly after, in 1901, Bangs published Mr. Munchausen, a collection of new Munchausen stories, closely following the style and humor of the original tales.[53] Pierre Henri Cami's character Baron de Crac, a French soldier and courtier under Louis XV,[55] is an imitation of the Baron Munchausen stories.[56]

Dramatic portrayals

Stage, radio, and audio

In 1932, the comedy writer Billy Wells adapted Baron Munchausen for a radio comedy routine starring the comedians Jack Pearl and Cliff Hall.[57] In the routine, Pearl's Baron would relate his unbelievable experiences in a thick German accent to Hall's "straight man" character, Charlie. When Charlie had had enough and expressed disbelief, the Baron would invariably retort: "Vass you dere, Sharlie?"[58] The line became a popular and much-quoted catchphrase, and by early 1933 The Jack Pearl Show was the second most popular series on the air (after Eddie Cantor's program).[58] Pearl attempted to adapt his portrayal to film in Meet the Baron in 1933, playing a modern character mistaken for the Baron,[58] but the film was not a success.[57] Pearl's popularity gradually declined between 1933 and 1937, though he staged several comebacks before ending his last radio series in 1951.[59]

On stage, Harlequin Munchausen, or the Fountain of Love, a pantomime based on the Raspe text, was produced in London in 1818.[52] Baron Prášil, a Czech musical about the Baron, opened in 2010 in Prague.[60] The following year, the National Black Light Theatre of Prague toured the United Kingdom with a nonmusical production of The Adventures of Baron Munchausen.[61]

For a 1972 Caedmon Records recording of some of the stories, Peter Ustinov voiced the Baron. A review in The Reading Teacher noted that Ustinov's portrayal highlighted "the braggadocio personality of the Baron," with "self-adulation … plainly discernible in the intonational innuendo."[62]

Film

The early French filmmaker Georges Méliès, who greatly admired the Baron Munchausen stories,[48] filmed Baron Munchausen's Dream in 1911. Méliès's short silent film, which has little in common with the Raspe text, follows a sleeping Baron through a surrealistic succession of intoxication-induced dreams.[63] Méliès may also have used the Baron's journey to the moon as an inspiration for his well-known 1902 film A Trip to the Moon.[48] In the late 1930s, he planned to collaborate with the Dada artist Hans Richter on a new film version of the Baron stories, but the project was left unfinished at his death in 1938.[64] Richter attempted to complete it the following year, taking on Jacques Prévert, Jacques Brunius, and fr as screenwriters, but the beginning of the Second World War put a permanent halt to the production.[65]

The French animator Emile Cohl produced a version of the stories using silhouette cutout animation in 1913; other animated versions were produced by Richard Felgenauer in Germany in 1920, and by Paul Peroff in the United States in 1929.[65] The British director F. Martin Thornton made a short silent film featuring the Baron, The New Adventures of Baron Munchausen, in 1915.[66]

For the German film studio Ufa's twenty-fifth anniversary in 1943, Joseph Goebbels hired the filmmaker Josef von Báky to direct Münchhausen, a big-budget color film about the Baron.[67] David Stewart Hull describes Hans Albers's Baron as "jovial but somewhat sinister,"[68] while Tobias Nagle writes that Albers imparts "a male and muscular zest for action and testosterone-driven adventure."[69]

In 1940, the Czech director Martin Frič filmed Baron Prášil, starring the comic actor Vlasta Burian.[f]

In 1961, the Czech director Karel Zeman directed Baron Prášil (Baron Munchausen), using animation and live actors.

In 1974 and 1975, four short cartoons were made in the Soviet Union (a fifth was made in 1995), called Münchhausen's Adventures.

In 1979, Mark Zakharov made a Russian film, based on a play by Grigori Gorin, The Very Same Munchhausen, relaying the story of the Baron's life after the adventures portrayed in the book.

A French cartoon version directed by Jean Image was made, called Les Fabuleuses Aventures du legendaire Baron de Munchausen (English: The Fabulous Adventures of Baron Munchausen). In 1984, a French cartoon sequel to the 1979 animated movie by Jean Image was made, called Le Secret des sélénites (English: Moon Madness).

In 1988, Terry Gilliam adapted the stories into a lavish Hollywood film, The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, with the Canadian stage actor John Neville in the lead. Roger Ebert, in his review of the film, described Neville's Baron as a man who "seems sensible and matter-of-fact, as anyone would if they had spent a lifetime growing accustomed to the incredible."[70]

Comics

In 1962, the stories were adapted to comic form for Classics Illustrated #146 (British series), with cover illustration by Denis Gifford.

Games

In 1998, James Wallis produced a multi-player storytelling/role-playing game titled The Extraordinary Adventures of Baron Munchausen.[71]

In 2012 JoyBits released a puzzle/hidden-object game called The Surprising Adventures of Munchausen.[72]

Memorials

Nomenclature

In 1951, the British physician Richard Asher published a Lancet article describing patients whose factitious disorders led them to lie about their own states of health. Asher proposed to call the disorder "Munchausen's syndrome," commenting: "Like the famous Baron von Munchausen, the persons affected have always travelled widely; and their stories, like those attributed to him, are both dramatic and untruthful. Accordingly, the syndrome is respectfully dedicated to the baron, and named after him".[13] The disease is now usually referred to as Munchausen syndrome.[73] The name has spawned two additional coinages: Munchausen syndrome by proxy, in which illness is feigned by caretakers rather than patients,[13] and Munchausen by internet, in which illness is feigned online.[74]

In 1968, the philosopher Hans Albert coined the term "Münchhausen Trilemma" to describe the philosophical problem inherent in having to derive conclusions from premises; those premises have to derived from still other premises, and so on forever, leading to an infinite regress interruptible only by circular logic or dogmatism. The problem is named after the similarly paradoxical story in which the Baron saves himself from being mired in a swamp by pulling on his hair.[75]

In 1994, a main belt asteroid was named 14014 Münchhausen in honor of both the real and the fictional Baron.[76]

Other memorials

There is a club "Munchausen's Grandchildren" (Внучата Мюнхаузена) in Kaliningrad (formerly Königsberg), Russia, which contains a number of "historical proofs" of the presence of the Baron in Königsberg, including the skeleton of the whale in whose belly the Baron was entrapped.[citation needed]

On 18 June 2005, to celebrate the 750th anniversary of Kaliningrad, a monument to the Baron was unveiled as a gift from Bodenwerder, portraying the Baron's cannonball ride.[77] A similar monument of the Baron is also installed in his city of birth, as well as a fountain of Münchhausen sitting on the front half of his horse.[citation needed]

An international tour of the places visited by Baron Münchhausen[which?] was established as a joint venture of Germany, Lithuania, Latvia, and Kaliningrad.[citation needed]

At Duntes Muiža, Latvia (German name: Dunteshof), home of the real Münchhausen's first wife Jacobine von Dunten, a Münchhausen Museum was opened in 2005. The couple had lived there between 1744 and 1750, before moving back to Bodenwerder. The Latvian central bank produced a commemorative coin on this occasion.

Notes

Footnotes

- ^ The German name for both the fictional character and his historical namesake is Münchhausen. The simplified spelling Munchausen, with one h and no umlaut, is standard in English when discussing the fictional character, as well as the medical conditions named for him.[1][2]

- ^ Both booksellers worked in Oxford and used the same London address, 46 Fleet Street, so it is possible that Kearsley had also been involved in some capacity with publication of the first and second editions.[17]

- ^ An Irish edition issued soon after (Dublin: P. Byrne, 1786) has the same text but is reset and introduces a few new typographical errors.[26]

- ^ A pirated reprint, with all the engravings except the new frontispiece, appeared the next year (Hamburgh: B. G. Hoffmann, 1790).[27]

- ^ At the time, "ludicrous" was not a negative term; rather, it suggested that humor in the book was sharply satirical.[25]

- ^ Among Czech speakers, the fictional Baron is usually called Baron Prášil.[65]

References

- ^ Olry 2002, p. 56.

- ^ a b c Fisher 2006, p. 257.

- ^ a b c d e f Krause 1886, p. 1.

- ^ Olry 2002, p. 53.

- ^ Fisher 2006, p. 251.

- ^ Kareem 2012, pp. 495–496.

- ^ a b Seccombe 1895, p. xxii.

- ^ Seccombe 1895, pp. xvi–xvii.

- ^ a b Blamires 2009, §3.

- ^ Blamires 2009, §8.

- ^ Seccombe 1895, pp. xix.

- ^ Krause 1886, p. 2.

- ^ a b c d e f g Olry 2002, p. 54.

- ^ a b c d e Fisher 2006, p. 252.

- ^ Carswell 1952, pp. 164–165.

- ^ Carswell 1952, pp. 166–167.

- ^ a b Carswell 1952, p. 167.

- ^ Carswell 1952, pp. 167–168.

- ^ Blamires 2009, §2.

- ^ a b Olry 2002, p. 55.

- ^ Krause 1886, p. 3.

- ^ a b Seccombe 1895, p. xi.

- ^ Seccombe 1895, p. x.

- ^ Seccombe 1895, p. xii.

- ^ a b Kareem 2012, p. 491.

- ^ Carswell 1952, pp. 165–166.

- ^ Carswell 1952, p. 173.

- ^ a b Carswell 1952, pp. 164–175.

- ^ a b George 1918, pp. 169–171.

- ^ Kareem 2012, p. 488.

- ^ a b Fisher 2006, p. 253.

- ^ George 1918, pp. 174–175.

- ^ Kareem 2012, p. 484.

- ^ George 1918, pp. 181–182.

- ^ Kareem 2012, p. 492.

- ^ a b Kareem 2012, p. 485.

- ^ George 1918, pp. 177–178.

- ^ Seccombe 1895, pp. xxxv–xxxvi.

- ^ Blamires 2009, §29.

- ^ Kareem 2012, p. 500.

- ^ Kareem 2012, pp. 500–503.

- ^ George 1918, pp. 179–180.

- ^ Wiebel 2011.

- ^ a b Seccombe 1895, p. vi.

- ^ Kareem 2012, p. 496.

- ^ George 1918, p. 169.

- ^ Seccombe 1895, p. v.

- ^ a b c Lefebvre 2011, p. 60.

- ^ Byington 1928, pp. v–vi.

- ^ a b Kareem 2012, p. 503.

- ^ Blamires 2009, §24.

- ^ a b Kareem 2012, p. 504.

- ^ a b Blamires 2009, §30.

- ^ Bangs 1895, p. 27; Bangs 1897, p. 27; Bangs 1899, p. 34.

- ^ Cami 1926.

- ^ George 1918, p. 175.

- ^ a b Erickson 2014, p. 50.

- ^ a b c Erickson 2014, p. 51.

- ^ Erickson 2014, p. 52.

- ^ Košatka 2010.

- ^ "The National Black Light Theatre of Prague: The Adventures of Baron Munchausen". Retrieved 1 November 2012.

- ^ Knight 1973, p. 119.

- ^ Zipes 2010, p. 43.

- ^ Ezra 2000, p. 20.

- ^ a b c Sadoul & Morris 1972, p. 25.

- ^ Young 1997, p. 441.

- ^ Hull 1969, pp. 252–253.

- ^ Hull 1969, p. 254.

- ^ Nagle 2010, p. 269.

- ^ Ebert 1989.

- ^ Varney, Allen (2007). "The Extraordinary Adventures of Baron Munchausen". In Lowder, James (ed.). Hobby Games: The Best 100. Green Ronin Publishing. pp. 107–109. ISBN 978-1-932442-96-0.

- ^ "The Surprising Adventures of Munchausen". Gamehouse. Retrieved 1 November 2012.

- ^ Fisher 2006, p. 250.

- ^ Feldman 2000.

- ^ Apel 2001, pp. 39–40.

- ^ NASA 2013.

- ^ "Münchhausen-Denkmal in Kaliningrad eingeweiht". Russland-Aktuell (in German). 22 June 2005. Retrieved 7 April 2011.

Citations

- "14014 Munchhausen (1994 AL16)", JPL Small-Body Database Browser, NASA, 2013, retrieved 3 February 2015

- Apel, Karl-Otto (2001), The Response of Discourse Ethics to the Moral Challenge of the Human Situation As Such and Especially Today, Leuven: Peeters

- Bangs, John Kendrick (1895), House-Boat on the Styx: Being Some Account of the Divers Doings of the Associated Shades, New York: Harper & Bros.

- Bangs, John Kendrick (1897), The Pursuit of the House-Boat: Being Some Further Account of the Divers Doings of the Associated Shades, Under the Leadership of Sherlock Holmes, Esq., New York: Harper & Bros.

- Bangs, John Kendrick (1899), The Enchanted Typewriter, New York: Harper & Bros.

- Blamires, David (2009), "The Adventures of Baron Munchausen", Telling Tales: The Impact of Germany on English Children's Books 1780–1918, Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, pp. 8–21

- Byington, Steven T. (1928), "Preface", Baron Munchausen's Narratives of His Marvelous Travels and Campaigns in Russia, Boston: Ginn and Co., pp. v–viii

- Cami, Pierre-Henri (1926), Les Aventures sans pareilles du baron de Crac, Paris: Hachette

- Carswell, John (1952), "Bibliography", in Raspe, Rudolf Erich (ed.), The Singular Adventures of Baron Munchausen, New York: Heritage Press, pp. 164–175

- Ebert, Roger (10 March 1989), "The Adventures of Baron Munchausen", RogerEbert.com, retrieved 3 January 2015

- Erickson, Hal (2014), From Radio to the Big Screen: Hollywood Films Featuring Broadcast Personalities and Programs, Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company

- Ezra, Elizabeth (2000), Georges Méliès, Manchester: Manchester University Press, ISBN 0-7190-5395-1

- Feldman, M. D. (July 2000), "Munchausen by Internet: detecting factitious illness and crisis on the Internet", Southern Medical Journal, 93 (7): 669–72, doi:10.1097/00007611-200093070-00006, PMID 10923952

- Fisher, Jill A (Spring 2006), "Investigating the Barons: narrative and nomenclature in Munchausen syndrome", Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 49 (2): 250–62, doi:10.1353/pbm.2006.0024, PMID 16702708

{{citation}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - George, W. L. (1918), "Three Comic Giants: Munchausen", Literary Chapters, Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, pp. 168–182

- Hull, David Stewart (1969), Film in the Third Reich: A Study of the German Cinema, 1933-1945, Berkeley: University of California Press

- Kareem, Sarah Tindal (May 2012), "Fictions, Lies, and Baron Munchausen's Narrative", Modern Philology, 109 (4): 483–509, doi:10.1086/665538, JSTOR 10.1086/665538

- Knight, Lester N. (October 1973), "The Story of Peter Pan; Baron Munchausen: Eighteen Truly Tall Tales by Raspe and Others by Raspe", The Reading Teacher, 27 (1): 117, 119, JSTOR 20193416

- Košatka, Pavel (1 March 2010), "Komplexní recenze nového muzikálového hitu "Baron Prášil"", Muzical.cz, retrieved 4 January 2015

- Template:Cite-ADB

- Lefebvre, Thierry (2011), "A Trip to the Moon: A Composite Film", in Solomon, Matthew (ed.), Fantastic Voyages of the Cinematic Imagination: Georges Méliès's Trip to the Moon, Albany: State University of New York Press, pp. 49–64, ISBN 978-1-4384-3581-7

- Nagle, Tobias (2010), "Projecting Desire, Rewriting Cinematic Memory: Gender and German Reconstruction in Michael Haneke's Fraulein", in Grundmann, Roy (ed.), A Companion to Michael Haneke, Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 263–278

- Olry, R. (June 2002), "Baron Munchhausen and the Syndrome Which Bears His Name: History of an Endearing Personage and of a Strange Mental Disorder" (PDF), Vesalius, VIII (1): 53–57, retrieved 2 January 2015

- Sadoul, Georges; Morris, Peter (1972), Dictionary of Films, Berkeley: University of California Press

- Seccombe, Thomas (1895), "Introduction", The Surprising Adventures of Baron Munchausen, London: Lawrence and Bullen, pp. v–xxxvi

- Wiebel, Bernhard (September 2011), "Munchausen – the difference between live and literature", Munchausen-Library, retrieved 4 January 2015

- Young, R. G. (1997), The Encyclopedia of Fantastic Film: Ali Baba to Zombies, New York: Applause

- Zipes, Jack (2010), The Enchanted Screen: The Unknown History of Fairy-Tale Films, New York: Routledge

External links

- Raspe's The Surprising Adventures of Baron Munchausen at Project Gutenberg

- Bürger's Münchhausen at Project Gutenberg Template:De icon

- The Munchausen Museum in Latvia

- The Munchausen Library in Zurich

- Use dmy dates from April 2011

- 1720 births

- 1797 deaths

- People from Holzminden (district)

- Literary characters

- Russian-German people

- German mercenaries

- People from the Electorate of Hanover

- Imperial Russian military personnel

- German folklore

- Barons of Germany

- Tall tales

- Fictional versions of real people

- Fictional characters based on real people

- Baron Münchhausen