Barto and Mann

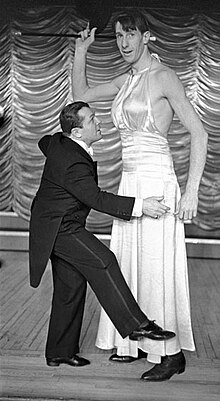

Barto and Mann: Dewey Barto (né Stewart Steven Swoyer; June 10, 1896 – January 31, 1973[1]) and George Mann (December 2, 1905 — November 22, 1977[2]), known as the "laugh kings" of vaudeville,[3] were a comedic dance act from the late 1920s to the early 1940s. Their acrobatic, somewhat risqué, performance played on their disparities in height; Barto was 4'11" and Mann was 6'6".

Fanchon and Marco

Initially dancing as singles in Fanchon and Marco's Variety Idea and Dancelogue Idea, Barto and Mann began dancing together as a comedic dance team in 1926 in Fanchon and Marco's Comic Supplement Idea, where they portrayed the International News Service comic strip characters, "Mutt and Jeff". By the end of 1926, they were well known throughout California as Barto and Mann.

Playing the Palace

Bypassing the lengthy path of seasoning on the vaudeville circuits usually required to “play the Palace” on Broadway (at 47th) in New York, William Morris of the William Morris Agency booked Barto and Mann “cold” into the Palace Theatre for March 14, 1927. Zit's Theatrical Newspaper[4] reported of their performance, “Ten minutes before they went on at the Palace last Monday afternoon nobody thought very much about Barto and Mann; ten minutes after they came off stage, the whole Broadway world was talking about them ... Acts like these only come along once in a while”.[5] They were an immediate sensation.[6] The Keith-Albee Theatre Circuit, the Orpheum Circuit, the Pantages Theatre Circuit, Loew's Inc., all of the picture houses, and several productions made offers.[7] They accepted a contract with the Orpheum Circuit.[8]

Earl Carroll's Vanities

Barto and Mann performed in New York, throughout the mid-West, and on the West Coast of the United States and Canada on the Orpheum Circuit until August 1928, when they joined the 7th edition of the Earl Carroll's Vanities in New York, which included W.C. Fields on the bill.[9] After a successful season with Vanities, the duo started touring again in February 1929 and began headlining for Fanchon and Marco's Fantasma Idea in April 1929. They toured Europe in 1931 and 1934,[10] were on the inaugural program of Radio City Music Hall in 1932,[11] and appeared in the 1933 film, Broadway Through a Keyhole.

Hellzapoppin

In October 1927, The Jazz Singer, the first feature-length motion picture with synchronized dialogue sequences, opened at the Warners’ Theatre, heralding the beginning of the end for vaudeville as a popular mode of American entertainment. Barto and Mann were headliners in theaters and clubs throughout the late 1920s and the 1930s, increasingly sharing their performances with feature films.

As vaudeville wound down in the 1930s, they joined Olsen and Johnson's hit Broadway show, Hellzapoppin from 1938 to 1941[12][13][14] and continued in the show on the road in 1942.[15] The duo dissolved the team in December 1943. Barto and Mann reunited briefly in late 1946 and early 1947.[16]

Post Barto and Mann partnership

Barto, father of actress Nancy Walker, continued to perform on stage and also became active in the American Guild of Variety Artists (AGVA) about the time the organization was formed in the late 1930s following the demise of the American Federation of Actors (AFA). He became head of the AGVA in the late 1940s. George Mann acted in small roles in several movies,[17] but primarily devoted himself to making a living with photography,[18][19] an activity he had pursued actively while in vaudeville.[20] Toward the end of his life he was the image on the box and character actor for the breakfast cereal, King Vitaman.[21]

See also

References

- ^ "California Death Index, 1940-1997". Ancestry.com.

{{cite web}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ "Ex-Broadway Dancer Dies in S[anta] M[onica] Home". Evening Outlook. November 26, 1977.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Green, Nat S. (June 2, 1929). "New Palace, Chicago". The Billboard.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "The Press: Zit's". Time. August 11, 1930. Retrieved August 23, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Keith-Albee Palace Track". Zit's Theatrical Newspaper. March 19, 1927.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Barto and Mann are listed in the appendix, "Fifty Years of Standard Acts (1880-1930)," in American Vaudeville: Its Life and Times by Douglas Gilbert (Whittlesey House, 1940)

- ^ "Barto and Mann in Demand". The Billboard. March 26, 1927.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Orpheum Circuit Wins Barto and Mann". The Billboard. April 9, 1927.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Carb, David (September 29, 1928). "Seen on the Stage". Vogue.

- ^ "London, Palladium". The Performer. June 17, 1931.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "The Inaugural Program of the Radio City Music Hall". Radio City Music Hall. December 27, 1932.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Thomas D. Fuller (2007). "The Songs and People of Hellzapoppin" (PDF). American Century Theater. Retrieved August 23, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Hellzapoppin: Vaudeville returns -- but with a screw loose". Life Magazine. October 24, 1938. p. 30. Retrieved August 23, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Hellzapoppin Souvenir Program". Bayles/Yeager Online Archives of the Performing Arts. 1940. Retrieved October 24, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Barto-Mann Explain How to Stay Partners and Happy". Pittsburgh Post Gazette. September 19, 1942.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Display ad". New York Times. December 17, 1946.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Filmography for George Mann". IMDb. Retrieved October 24, 2010.

- ^ Michelle Gringeri-Brown (Fall 1997). "George Mann: New American Master". Photographer's Forum. pp. 13–18.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Meet George Mann". On Bunker Hill. May 30, 2010. Retrieved October 24, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Josef Woodard (July 8, 1983). "Touching Photographs Capture Vaudeville in Its Dying Days: An exhibit of the work of George Mann takes viewers behind the scenes of a bygone era". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 26, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "King Vitaman". Quaker Oats. Retrieved October 25, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help)