Battle of McDowell

| Battle of McDowell | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Robert H. Milroy Robert C. Schenck | Stonewall Jackson | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 6,500[1] | 6,000[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

259 total 34 killed 220 wounded 5 missing [2] |

420 total 116 killed 300 wounded 4 missing[2] | ||||||

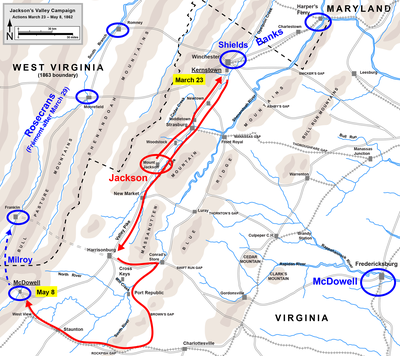

The Battle of McDowell, also known as Sitlington's Hill, was fought May 8, 1862, in Highland County, Virginia, as part of Confederate Army Maj. Gen. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's Campaign through the Shenandoah Valley during the American Civil War. It followed Jackson's tactical defeat, but strategic victory, at the First Battle of Kernstown.

Background

Jackson's columns departed West View and Staunton, Virginia, on the morning of May 7, marching west along the Parkersburg turnpike. Elements of Brig. Gen. Edward "Allegheny" Johnson's brigade composed the vanguard. At mid-afternoon, Union pickets were encountered at Rodgers' tollgate, where the pike crosses Ramsey's Draft. The Union force, which consisted of portions of three regiments (3rd West Virginia, 32nd Ohio, and 75th Ohio) under overall command of Brig. Gen. Robert H. Milroy, withdrew hastily, abandoning their baggage at the tollgate and retreating to the crest of Shenandoah Mountain.

The Confederate force split into two columns to envelope the Union holding position on Shenandoah Mountain. Milroy ordered his force to withdraw and concentrate at McDowell, where he hoped to receive reinforcements. Milroy also positioned a section of artillery on Shaw's Ridge to impede Johnson's descent from the crest of Shenandoah Mountain. These guns were soon withdrawn with their supports to McDowell. By dusk, Johnson's advance regiments reached Shaw's Fork, where they encamped. Because of the narrow roads and few camp sites, Jackson's army was stretched 8–10 miles back along the pike with its rear guard at Dry Branch Gap. Jackson established his headquarters at Rodgers's tollgate. During the night, Milroy withdrew behind the Bullpasture River to McDowell, establishing headquarters in the Hull House.

Opposing forces

Union

Confederate

Battle

Starting at dawn on May 8, the Confederate advance crossed Shaw's Ridge, descended to the Cowpasture River at Wilson's House, and ascended Bullpasture Mountain. The advance was unopposed. Reaching the crest of the ridge, Jackson and his mapmaker, Jedediah Hotchkiss, conducted a reconnaissance of the Union position at McDowell from a rocky spur right of the road. Johnson continued with the advance to the base of Sitlington's Hill. Expecting a roadblock ahead, he diverged from the road into a steep narrow ravine that led to the top of the hill. After driving away Union skirmishers, Johnson deployed his infantry along the long, sinuous crest of the hill. Jackson asked his staff to find a way to place artillery on the hill and to search for a way to flank the Union position to the north.[3]

About 10 a.m., Brig. Gen. Robert C. Schenck arrived after a forced march from Franklin, West Virginia. Being senior to Milroy, Schenck assumed overall command of the Union force at McDowell with headquarters at the Hull House. He deployed his artillery, consisting of 18 guns, on Cemetery Hill and near the McDowell Presbyterian Church to defend the bridge over the Bullpasture River. He deployed his infantry in line from McDowell south along the river for about 800 yards. He placed one regiment (2nd West Virginia) on Hull's Hill, east of the river and overlooking the pike. Three companies of cavalry covered the left flank on the road to the north of the village.[3]

Schenck and Milroy sent out skirmishers to contest the base of Sitlington's Hill along the river. As Confederate forces on the crest of the hill increased in numbers, Schenck and Milroy conferred. Union scouts reported that the Confederates were attempting to bring artillery to the crest of the hill, which would make the Union position on the bottomland at McDowell untenable. In absence of an aggressive Confederate advance, Schenck and Milroy attempted a spoiling attack. Milroy advanced his brigade (25th Ohio, 32nd Ohio, 75th Ohio, 3rd West Virginia) and the 82nd Ohio of Schenck's brigade, about 2,300 men. About 3 p.m. Milroy personally led the attacking force, which crossed the bridge and proceeded up the ravines that cut the western slope of the hill.[3]

In the meantime, Jackson had been content to hold the crest of the hill while searching for a route for a flanking movement to the north. He had decided against sending artillery up the hill because of the difficulty of withdrawing the pieces in the face of an attack. Union artillerymen on Cemetery Hill elevated their pieces by digging deep trenches in the ground for the gun trails and began firing at the Confederates in support of the advancing infantry. Schenck also had a six-pounder hauled by hand to the crest of Hull's Hill to fire on the Confederate right flank above the turnpike (some accounts say a section of guns, another says a whole battery). The Union line advanced resolutely up the steep slopes and closed on the Confederate position. The conflict became "fierce and sanguinary".[3]

The 3rd West Virginia advanced along the turnpike in an attempt to turn the Confederate right. Jackson reinforced his right on the hill with two regiments and covered the turnpike with the 21st Virginia. The 12th Georgia at the center and slightly in advance of the main Confederate line on the hill crest bore the brunt of the Union attack and suffered heavy casualties. This was largely due to the fact that the regiment was armed with smoothbore muskets and were consequently unable to do much damage to the rifle-equipped Federals.[4] The fighting continued for four hours as the Union attackers attempted to pierce the center of the Confederate line and then to envelope its left flank. Nine Confederate regiments were engaged, opposing five Union regiments in the fight for Sitlington's Hill. At dusk the Union attackers withdrew to McDowell.[3]

Aftermath

At dark, Union forces withdrew from Sitlington's Hill and recrossed to McDowell, carrying their wounded from the field. Union casualties were 259 (34 killed, 220 wounded, five missing), Confederate 420 (116 killed, 300 wounded, four missing), one of the rare cases in the Civil War where the attackers lost fewer men than the defenders.[2] About 2 a.m., on May 9, Schenck and Milroy ordered a general retreat along the turnpike toward Franklin. The 73rd Ohio held their skirmish line along the river until near dawn, when they withdrew and acted as rear guard for the retreating column. Ten men of the regiment were inadvertently left behind and captured. Shortly after the Federals retired, the Confederates entered McDowell. Schenck established a holding position on May 9, but only minor skirmishing resulted. For nearly a week, Jackson pursued the retreating Union army almost to Franklin before commencing a return march to the valley on May 15.[3]

Some historians consider the battle of McDowell the beginning of Jackson's 1862 Valley Campaign, while others prefer to include the First Battle of Kernstown, Stonewall's only defeat. The battle of McDowell is studied today by military historians for several reasons. At the tactical level, it can be argued that the Union forces achieved a draw. Milroy's "spoiling attack" surprised Jackson, seized the initiative, and inflicted heavier casualties, but did not drive the Confederates from their position. At the strategic level, the battle of McDowell and the resultant withdrawal of the Union army was an important victory for the South. The battle demonstrated Jackson's strategy of concentrating his forces against a numerically inferior foe, while denying his enemies the chance to concentrate against him. Jackson rode the momentum of his strategic win at McDowell to victory at Front Royal (May 23) and First Winchester (May 25).[3]

See also

Notes

- ^ a b NPS Archived February 21, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Salmon, p. 38; Cozzens, p. 273, cites Union casualties of 259 (26 killed, 230 wounded, and 3 missing), and Confederate casualties of 532 (146 killed, 382 wounded, and 4 missing); Eicher, p. 259, cites Union casualties of 256 (26 killed, 227 wounded, and 3 missing), and Confederate casualties of 498 (75 killed and 423 wounded); the NPS Archived February 21, 2006, at the Wayback Machine reports 720 total.

- ^ a b c d e f g NPS report on battlefield condition Archived October 28, 2004, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Cozzens, p. 268.

References

- Cozzens, Peter. Shenandoah 1862: Stonewall Jackson's Valley Campaign. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0-8078-3200-4.

- Eicher, David J. The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0-684-84944-5.

- Salmon, John S. The Official Virginia Civil War Battlefield Guide. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2001. ISBN 0-8117-2868-4.

- National Park Service battle description

- Template:NPS.Gov

External links

- Battle of McDowell in Encyclopedia Virginia

- The Battle of McDowell: Battle maps, history articles, photos, and preservation news (Civil War Trust)

- CWSAC Report Update