Bel canto

Bel canto (Italian for "beautiful singing" or "beautiful song", pronounced [bɛl ˈkanto]), along with a number of similar constructions ("bellezze del canto"/"bell'arte del canto"), is a term relating to Italian singing. It has several different meanings and is subject to a wide variety of interpretations.[1]

The words were not associated with a "school" of singing until the middle of the 19th century, when writers in the early 1860s used it nostalgically to describe a manner of singing that had begun to wane around 1830.[2] Nonetheless, "neither musical nor general dictionaries saw fit to attempt [a] definition [of bel canto] until after 1900". The term remains vague and ambiguous in the 21st century and is often used to evoke a lost singing tradition.[3]

History of the term and its various definitions

As generally understood today, the term bel canto refers to the Italian-originated vocal style that prevailed throughout most of Europe during the 18th century and early 19th centuries. Late 19th- and 20th-century sources "would lead us to believe that bel canto was restricted to beauty and evenness of tone, legato phrasing, and skill in executing highly florid passages, but contemporary documents [those of the late 18th and early 19th centuries] describe a multifaceted manner of performance far beyond these confines."[4] The main features of the bel canto style were:[4]

- prosodic singing (use of accent and emphasis)

- matching register and tonal quality of the voice to the emotional content of the words

- a highly articulated manner of phrasing based on the insertion of grammatical and rhetorical pauses

- a delivery varied by several types of legato and staccato

- a liberal application of more than one type of portamento

- messa di voce as the principal source of expression (Domenico Corri called it the "soul of music" – The Singer's Preceptor, 1810, vol. 1, p. 14)

- frequent alteration of tempo through rhythmic rubato and the quickening and slowing of the overall time

- the introduction of a wide variety of graces and divisions into both arias and recitatives

- gesture as a powerful tool for enhancing the effect of the vocal delivery

- vibrato primarily reserved for heightening the expression of certain words and for gracing longer notes.

Bel canto in the 18th and early 19th centuries

Since the bel canto style flourished in the 18th and early 19th centuries, the music of Handel and his contemporaries, as well as that of Mozart and Rossini, benefits from an application of bel canto principles. Operas received the most dramatic use of the techniques, but the bel canto style applies equally to oratorio, though in a somewhat less flamboyant way. The da capo arias these works contained provided challenges for singers, as the repeat of the opening section prevented the story line from progressing. Nonetheless, singers needed to keep the emotional drama moving forward, and so they used the principles of bel canto to help them render the repeated material in a new emotional guise. They also incorporated embellishments of all sorts (Domenico Corri said da capo arias were invented for that purpose [The Singer's Preceptor, vol. 1, p. 3]), but not every singer was equipped to do this, some writers, notably Domenico Corri himself, suggesting that singing without ornamentation was an acceptable practice (see The Singer's Preceptor, vol. 1, p. 3). Singers regularly embellished both arias and recitatives, but did so by tailoring their embellishments to the prevailing sentiments of the piece.[5]

Two famous 18th-century teachers of the style were Antonio Bernacchi (1685–1756) and Nicola Porpora (1686–1768), but many others existed. A number of these teachers were castrati. Singer/author John Potter declares in his book Tenor: History of a Voice that:

- For much of the 18th century castrati defined the art of singing; it was the loss of their irrecoverable skills that in time created the myth of bel canto, a way of singing and conceptualizing singing that was entirely different from anything that the world had heard before or would hear again.[6]

Bel canto in 19th-century Italy and France

In another application, the term bel canto is sometimes attached to Italian operas written by Vincenzo Bellini (1801–1835) and Gaetano Donizetti (1797–1848). These composers wrote bravura works for the stage during what musicologists sometimes call the "bel canto era". But the style of singing had started to change around 1830, Michael Balfe writing of the new method of teaching that was required for the music of Bellini and Donizetti (A New Universal Method of Singing, 1857, p. iii),[7] and so the operas of Bellini and Donizetti actually were the vehicles for a new era of singing. The last important opera role for a castrato was written in 1824 by Giacomo Meyerbeer [1791–1864].[8]

The phrase "bel canto" was not commonly used until the latter part of the 19th century, when it was set in opposition to the development of a weightier, more powerful style of speech-inflected singing associated with German opera and, above all, Richard Wagner's revolutionary music dramas. Wagner (1813–1883) decried the Italian singing model, alleging that it was concerned merely with "whether that G or A will come out roundly". He advocated a new, Germanic school of singing which would draw "the spiritually energetic and profoundly passionate into the orbit of its matchless Expression".[9]

Interestingly enough, French musicians and composers never embraced the more florid extremes of the 18th-century Italian bel canto style. They disliked the castrato voice and because they placed a premium on the clear enunciation of the texts of their vocal music, they objected to the sung word being obscured by excessive fioritura.

The popularity of the bel canto style as espoused by Rossini, Donizetti and Bellini faded in Italy during the mid-19th century. It was overtaken by a heavier, more ardent, less embroidered approach to singing that was necessary in order to perform the innovative works of Giuseppe Verdi (1813–1901) with maximum dramatic impact. Tenors, for instance, began to inflate their tone and deliver the high C (and even the high D) directly from the chest rather than resorting to a suave head voice/falsetto as they had done previously—sacrificing vocal agility in the process. Sopranos and baritones reacted in a similar fashion to their tenor colleagues when confronted with Verdi's drama-filled compositions. They subjected the mechanics of their voice production to greater pressures and cultivated the exciting upper part of their respective ranges at the expense of their mellow but less penetrant lower notes. Initially at least, the singing techniques of 19th-century contraltos and basses were less affected by the musical innovations of Verdi, which were built upon by his successors Amilcare Ponchielli (1834–1886) and Arrigo Boito (1842–1918).

Bel canto and its detractors

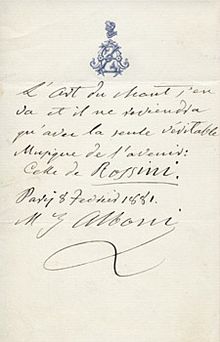

One reason for the eclipse of the old Italian singing model was the growing influence within the music world of bel canto's detractors, who considered it to be outmoded and condemned it as vocalization devoid of content. To others, however, bel canto became the vanished art of elegant, refined, sweet-toned musical utterance. Rossini lamented in a conversation that took place in Paris in 1858 that: "Alas for us, we have lost our bel canto".[10] Similarly, the so-called German style was as derided as much as it was heralded. In the introduction to a collection of songs by Italian masters published in 1887 in Berlin under the title Il bel canto, Franz Sieber wrote: "In our time, when the most offensive shrieking under the extenuating device of 'dramatic singing' has spread everywhere, when the ignorant masses appear much more interested in how loud rather than how beautiful the singing is, a collection of songs will perhaps be welcome which – as the title purports – may assist in restoring bel canto to its rightful place."[8]

In the late-19th century and early-20th century, the term "bel canto" was resurrected by Italy's singing teachers, among whom the retired Verdi baritone Antonio Cotogni (1831–1918) was perhaps the pre-eminent figure. Cotogni and his followers invoked it against an unprecedentedly vehement, unsubtle and vibrato-laden style of vocalism which was being adopted by more and more post-1890 singers in order to cope with the impassioned demands of the stream of verismo operas that were flowing from the pens of Giacomo Puccini (1858–1924), Ruggero Leoncavallo (1857–1919), Pietro Mascagni (1863–1945) and Umberto Giordano (1867–1948); and the auditory challenges posed by the non-Italianate stage works of Richard Strauss (1864–1949) and other late-romantic/early modern era composers, with their strenuous and angular vocal lines and often thick orchestral textures.

To make the situation worse, during the 1890s, the directors of the Bayreuth Festival began propagating a particularly forceful style of Wagnerian singing that placed such an undue emphasis on the articulation of the individual words of the composer's libretti, the all-important musical component of his operas was compromised. Called "Sprechgesang" by its proponents and the "Bayreuth bark" by its opponents, this hectoring, text-based, anti-legato approach to vocalism spread across the German-speaking parts of Europe prior to World War I. It was totally at odds with the Italian ideals of "beautiful singing".

As a result of these many factors, the concept of bel canto became shrouded in mystique and confused by a plethora of individual notions and interpretations. To complicate matters further, German musicology in the early 20th century invented its own historical application for "bel canto", using the term to denote the simple lyricism that came to the fore in Venetian opera and the Roman cantata during the 1630s and '40s (the era of composers Antonio Cesti, Giacomo Carissimi and Luigi Rossi) as a reaction against the earlier, text-dominated "stilo rappresentativo".[1] Unfortunately, this anachronistic use of the term bel canto was given wide circulation in Robert Haas's Die Musik des Barocks[11] and, later, in Manfred Bukofzer's Music in the Baroque Era.[12] Since the singing style of later 17th-century Italy did not differ in any marked way from that of the 18th century and early 19th century, a connection can be drawn; but, according to Jander, most musicologists agree that the term is best limited to its mid-19th-century use, designating a style of singing that emphasized beauty of tone and technical expertise in the delivery of music that was either highly florid or featured long, flowing and difficult-to-sustain passages of cantilena.[8]

The bel canto revival

In the 1950s, the phrase "bel canto revival" was coined to refer to a renewed interest in the operas of Donizetti, Rossini and Bellini. These composers had begun to go out of fashion during the latter years of the 19th century and their works, while never completely disappearing from the performance repertoire, were staged infrequently during the first half of the 20th century, when the operas of Wagner, Verdi and Puccini held sway. That situation changed significantly after World War II with the advent of a group of enterprising orchestral conductors and the emergence of a fresh generation of singers such as Montserrat Caballé, Maria Callas, Joan Sutherland, and Marilyn Horne, who had acquired bel canto techniques. These artists breathed new life into Donizetti, Rossini and Bellini's stage compositions, treating them seriously as music and re-popularizing them throughout Europe and America.[13] Today, some of the world's most frequently performed operas, such as Rossini's The Barber of Seville and Donizetti's Lucia di Lammermoor, are from the bel canto era.[14]

Not coincidentally, the 18th-century operas of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791), which require adroit bel canto skills if they are to be performed well, also experienced a post-war revival that shows no sign of abating, while the florid operas composed by Mozart's predecessor Handel have undergone a similar surge in popularity during recent decades. "I should think that performances of Handel operas now outnumber all others" avers classical music commentator Simon Callow in the April 2010 issue of Gramophone magazine.[15]

The bel canto teaching legacy

Musicologists occasionally apply the label "bel canto technique" to the arsenal of virtuosic vocal accomplishments and concepts imparted by singing teachers to their students during the late 18th century and the early 19th century. Many of these teachers were castrati.

"All [their] pedagogical works follow the same structure, beginning with exercises on single notes and eventually progressing to scales and improvised embellishments" writes Potter[16] who continues, "The really creative ornamentation required for cadenzas, involving models and formulae that could generate newly improvised material, came towards the end of the process."

Today's pervasive idea that singers should refrain from improvising and always adhere strictly to the letter of a composer's published score is a comparatively recent phenomenon, promulgated during the first decades of the 20th century by dictatorial conductors such as Arturo Toscanini [1867–1957], who championed the dramatic operas of Verdi and Wagner and believed in keeping performers on a tight interpretive leash. This is noted by both Potter (page 77) and Michael Scott[17]

Potter notes, however, that as the 19th century unfurled:

- The general tendency ... was for singers not to have been taught by castrati (there were few of them left) and for serious study to start later, often at one of the new conservatories rather than with a private teacher. The traditional techniques and pedagogy were still acknowledged, but the teaching was generally in the hands of tenors and baritones who were by then at least once removed from the tradition itself.

Early 19th-century teachers described the voice as being made up of three registers. The chest register was the lowest of the three and the head register the highest, with the passaggio in between. These registers needed to be smoothly blended and fully equalized before a trainee singer could acquire total command of his or her natural instrument, and the surest way to achieve this outcome was for the trainee to practise vocal exercises assiduously. Bel canto-era teachers were great believers in the benefits of vocalise and solfeggio. They strove to strengthen the respiratory muscles of their pupils and equip them with such time-honoured vocal attributes as "purity of tone, perfection of legato, phrasing informed by eloquent portamento, and exquisitely turned ornaments", as noted in the introduction to Volume 2 of Scott's The Record of Singing.

Major refinements occurred to the existing system of voice classification during the 19th century as the international operatic repertoire diversified, split into distinctive nationalist schools and expanded in size. Whole new categories of singers such as mezzo-soprano and Wagnerian bass-baritone arose towards the end of the 19th century, as did such new sub-categories as lyric coloratura soprano, dramatic soprano and spinto soprano, and various grades of tenor, stretching from lyric through spinto to heroic. These classificatory changes have had a lasting effect on the way singing teachers designate voices and the way in which opera house managements cast their productions.

It would be wrong, however, to think that there was across-the-board uniformity among 19th-century bel canto adherents when it came to passing on their knowledge and instructing students. Each of them had their own training regimes and pet notions; but, fundamentally, they all subscribed to the same set of bel canto precepts, and the exercises that they devised in order to enhance their students' breath support, dexterity, range and technical control remain valuable and, indeed, are still employed by some teachers.[1]

Manuel García (1805–1906), author of the influential treatise L'Art du Chant, was the most prominent of the group of pedagogues that perpetuated bel-canto principles in their teachings and writings during the second half of the 19th century. His like-minded younger sister, Pauline Viardot (1821–1910), was also an important teacher of voice, as were Viardot's contemporaries Mathilde Marchesi, Camille Everardi, Julius Stockhausen, Carlo Pedrotti, Venceslao Persichini, Giovanni Sbriglia, Melchiorre Vidal and Francesco Lamperti (together with Francesco's son Giovanni Battista Lamperti). The voices of a number of their former students can be heard on acoustic recordings made in the first two decades of the 20th century and re-issued since on LP and CD. Some examples on disc of historically and artistically significant 19th-century singers whose bel canto-infused vocal styles and techniques pre-date the "Bayreuth bark" and the dramatic excesses of verismo opera are:

Sir Charles Santley (born 1834), Gustav Walter (born 1834), Adelina Patti (born 1843), Marianne Brandt (born 1842), Lilli Lehmann (born 1848), Jean Lassalle (born 1847), Victor Maurel (born 1848), Marcella Sembrich (born 1858), Lillian Nordica (born 1857), Emma Calvé (born 1858), Nellie Melba (born 1861), Francesco Tamagno (born 1850), Francesco Marconi (born 1853), Léon Escalais (born 1859), Mattia Battistini (born 1856), Mario Ancona (born 1860), Pol Plançon (born 1851), and Antonio Magini-Coletti and Francesco Navarini (both born 1855).

Quotations

- "There are no registers in the human singing voice when it is accurately produced. According to natural laws of voice, it is made up of one register that constitutes its entire range"[18]

- "Bel-canto is not a school of sensuously pretty voice-production.[19] It has come to be a generally recognised thing that voice, pure and simple, by its very composition, or "placing", interferes with the organs of speech; making it impossible for a vocalist to preserve absolute purity of pronunciation in song as well as in speech. It is because of this view that the principle of "vocalising" words, instead of musically "saying" them, crept in, to the detriment of vocal art. This false position is due to the idea that the 'Arte del bel-canto' encouraged mere sensuous beauty of voice, rather than truth of expression."[19]

- "Bel-canto (of which we read so much) meant, and means, versatility of tone; if a man wish to be called an 'artist', his voice must become the instrument of intelligent imagination. Perhaps there would be fewer cases of vocal-specialising if the modern craze for 'voice-production' (apart from linguistic truth) could be reduced. This wondrous pursuit is, as things stand, a notable instance of putting the cart before the horse. Voices are 'produced' and 'placed' in such wise that pupils are trained to 'vocalise' (to use technical jargon) the words; i.e., they are taught to make a sound which is indeed 'something like' but is not the word in its purity. 'Tone' or sound is what the average student seeks, ab initio and not verbal purity. Hence the monotony of modern singing. When one hears an average singer in one role, one hears him in all."[20]

- "Those who regard the art of singing as anything more than a means to an end, do not comprehend the true purpose of that art, much less can they hope ever to fulfil that purpose. The true purpose of singing is to give utterance to certain hidden depths in our nature which can be adequately expressed in no other way. The voice is the only vehicle perfectly adapted to this purpose; it alone can reveal to us our inmost feelings, because it is our only direct means of expression. If the voice, more than any language, more than any other instrument of expression, can reveal to us our own hidden depths, and convey those depths to other souls of men, it is because voice vibrates directly to the feeling itself, when it fulfils its 'natural' mission. By fulfilling its natural mission, I mean, when voice is not hindered from vibrating to the feeling by artificial methods of tone production, which methods include certain mental processes which are fatal to spontaneity. To sing should always mean to have some definite feeling to express."[21]

- "The decline of Bel Canto may be attributed in part to Ferrein and Garcia who, with a dangerously small and historically premature knowledge of laryngeal function, abandoned the intuitive and emotional insight of the anatomically blind singers."[22]

- "Voice Culture has not progressed [...]. Exactly the contrary has taken place. Before the introduction of mechanical methods every earnest vocal student was sure of learning to use his voice properly, and of developing the full measure of his natural endowments. Mechanical instruction has upset all this. Nowadays the successful vocal student is the exception."[23]

References

Notes

- ^ a b c Stark 2003, p. ?

- ^ Toft, Bel Canto: A Performer's Guide, pp. 3–4

- ^ Duey 1951, p. ?

- ^ a b Toft, Bel Canto: A Performer's Guide, 2013, p. 4

- ^ Toft, Bel Canto: A Performer's Guide, pp. 140, 163

- ^ Potter 2009, p. 31

- ^ Toft, Bel Canto: A Performer's Guide, p. 92

- ^ a b c Jander 1998, pp. 380—381

- ^ Fischer, J. M. (1993). "Sprechgesang oder Belcanto". Grosse Stimmen: 229–91.

- ^ Osborne 1994, p. 1

- ^ Hass 1928, p. ??

- ^ Bukofzer 1947, p. ??

- ^ "Opera: Back to Bel Canto", Time magazine, 20 January 1967

- ^ Opera statistics on operabase.com

- ^ Gramophone (London), April 2010, p. 26)

- ^ Potter 2009, p. 47

- ^ Scott 1971, pp. 135–136

- ^ Marafoti 1981, p. ??

- ^ a b Ffrangcon-Davies 1907, p. 16

- ^ Ffrangcon-Davies 2007, Vol. 2, p. 14

- ^ Rogers 1893, p. 33

- ^ Newham 1999, p. 55

- ^ Taylor 1917, p. 344

Sources

- Duey, Philip A. (1951). Bel canto in its Golden Age. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-1-4067-5437-7.

- Ffrangcon-Davies, David (1907), The singing of the future,

- Jander, Owen (1998), "Bel canto" in Stanley Sadie, (Ed.), The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, Vol. One. London: MacMillan Publishers, Inc. ISBN 0-333-73432-7 ISBN 1-56159-228-5

- Juvarra, Antonio (2006) I segreti del belcanto. Storia delle tecniche e dei metodi vocali dal '700 ai nostri giorni, Curci, 2006

- Marafoti, P. Mario (1981), Caruso's Method of Voice Production: The Scientific Culture of the Voice, New York: Dover Books, ISBN 0-486-24180-7

- Newham, Paul (1999), Using voice and song in therapy: the practical application of voice movement therapy

- Osborne, Charles (1994), The Bel Canto Operas of Rossini, Donizetti, and Bellini, Hal Leonard Corporation; Portland, Oregon: Amadeus Press. ISBN 0-931340-84-5

- Potter, John (2009), Tenor: History of a Voice, Yale University Press, New Haven & London. ISBN 978-0-300-11873-5

- Rogers, Clara Kathleen (1893), The Philosophy Of Singing

- Scott, Michael (1977), The Record of Singing, Vols. 1 and 2. London: Duckworth. ISBN 0-7156-1030-9 ISBN 1-55553-163-6

- Stark, James (2003). Bel Canto: A History of Vocal Pedagogy. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-8614-3.

- Taylor, David C. (1917), The psychology of singing; a rational method of voice culture based on a scientific analysis of all systems, ancient and modern

- Toft, Robert (2013), Bel Canto: A Performer's Guide. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-983232-3

Further reading

- Brown, M. Augusta (1894), University of Pennsylvania "Extracts From Vocal Art" in The Congress of Women, Mary Kavanaugh Oldham (ed.), Chicago: Monarch Book Company, p. 477.

- Coffin, Berton (2002), Sounds of Singing, Second Edition, Littlefield.

- Christiansen, Rupert (15 March 2002), "A tenor for the 21st century", The Daily Telegraph Accessed 3 November 2008.

- Marchesi, Mathilde (1970), Bel Canto: A Theoretical and Practical Vocal Method, Dover. ISBN 0-486-22315-9

- Pleasants, Henry (1983), The Great Singers from the Dawn of Opera to Our Own Time, London: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 0-333-34854-0

- Roselli, John (1995), Singers of Italian Opera: The History of a Profession, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-42697-9

- Rushmore, Robert (1971), The Singing Voice, London: Hamish Hamilton. ISBN 9780241019474

- Somerset-Ward, Richard (2004), Angels and Monsters: Male and Female Sopranos in the Story of Opera, New Haven & London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09968-1

- Reid, Cornelius L. (1950), Bel Canto: Principles and Practices, Joseph Patelson Music House ISBN 0-915282-01-1

- Rosenthal, Harold; Ewan West (eds.) (1996), The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Opera, London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-311321-X

- Scalisi, Cecilia (November 10, 2003), "Raúl Giménez, el maestro del bel canto", La Nación. Accessed 3 November 2008.

- Toft, Robert (1993), Tune thy Musicke to thy Hart: The Art of Eloquent Singing in England 1597-1622. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-2848-9

- Toft, Robert (2000), Heart to Heart: Expressive Singing in England 1780–1830. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-816662-1

- Toft, Robert (2014), With Passionate Voice: Re-Creative Singing in Sixteenth-Century England and Italy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-938203-3

- Traité complet de chant et de déclamation lyrique Enrico Delle Sedie (Paris, 1847) fragment

External links

Articles

- Bel Canto: Historically Informed, Re-Creative Singing in the Age of Rhetorical Persuasion, c.1500 – c.1830

- Nigro, Antonella, Observations on the Technique of Italian Singing from the 16th Century to the Present Day from the book "Celebri Arie Antiche: le piu' note arie del primo Barocco italiano trascritte e realizzate secondo lo stile dell'epoca" by Claudio Dall'Albero and Marcello Candela. (ref)

- Samoiloff, Lazar S. (1942), "Bel Canto", The Singer's Handbook

Digitized, scanned material

- "Bel Canto" Titles from the Internet Archive (e.g. Lamperti, Giovanni Battista: The Technics of Bel Canto)

- Garcia, Manuel; Garcia, Beata, (trans.) (1894). Hints on singing, London: E. Ascherberg.

- Greene, Harry Plunket (1912), Interpretation in Song. New York: The Macmillan Company.

- Lehmann, Lilli; Aldrich, Richard, (trans.) (1902), How to sing, New York: Macmillan & Co. Ltd.