Blue duck

| Blue duck | |

|---|---|

| |

| Blue duck at Staglands, Akatarawa Valley | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Anseriformes |

| Family: | Anatidae |

| Genus: | Hymenolaimus G.R. Gray, 1843 |

| Species: | H. malacorhynchos

|

| Binomial name | |

| Hymenolaimus malacorhynchos (Gmelin, JF, 1789)

| |

| Subspecies | |

|

See text | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Anas malacorhynchus (protonym) | |

The blue duck or whio (Hymenolaimus malacorhynchos) is a member of the duck, goose and swan family Anatidae endemic to New Zealand. It is the only member of the genus Hymenolaimus. Its exact taxonomic status is still unresolved, but it appears to be most closely related to the tribe Anatini, the dabbling ducks.

The whio is depicted on the reverse side of the New Zealand $10 banknote.

Taxonomy

[edit]Captain James Cook saw the blue duck in Dusky Sound, South Island, New Zealand, on his second voyage to the south Pacific. In 1777 both Cook and the naturalist Georg Forster mentioned the blue duck in their separate accounts of the voyage.[2][3] A specimen was described in 1785 by the English ornithologist John Latham in his A General Synopsis of Birds. Latham used the English name, the "soft-billed duck".[4] When in 1789 the German naturalist Johann Friedrich Gmelin revised and expanded Carl Linnaeus's Systema Naturae he included the blue duck and placed it with all the other ducks in the genus Anas. He coined the binomial name Anas malacorhynchos and cited the earlier works.[5] The blue duck is now the only species placed in the genus Hymenolaimus that was introduced specifically for the species by George Robert Gray in 1843.[6][7] The genus name combines the Ancient Greek humēn, humenos meaning "skin" or "membrane" with laimos meaning "throat". The specific epithet malacorhynchos is also from Ancient Greek and combines malakos meaning "soft" with rhunkhos meaning "bill".[8]

The species has no close relatives.[9] Its taxonomic relationships with other waterfowl species remains uncertain; DNA analysis has placed it as a sister to the South American dabbling ducks (Anatini), but with no close relative. As of 2013, it was commonly listed as incertae sedis but likely within the Anatinae and allied to the Anatini.[10] It was formerly thought to be related to the shelduck tribe.[11][12]

It is commonly known in New Zealand English by its Māori name Whio, pronounced /ˈfiɔː/ FEE-oh, which is an onomatopoeic rendition of the males' call.[13][14] Other names it may be known by are Mountain Duck or Blue Mountain Duck.[14]

Two subspecies are recognised:[7]

- H. m. hymenolaimus Mathews, 1937 – central, south North Island (New Zealand)

- H. m. malacorhynchos (Gmelin, JF, 1789) – west South Island (New Zealand)

Prior to 2022, the North Island and South Island whio were considered distinct but were not distinguished as subspecies; they were, however, treated as separate management units.[15] However, the populations were defined as distinct subspecies by the International Ornithological Congress in 2022, based on strong genetic divergence and some plumage differences.[7]

Description

[edit]

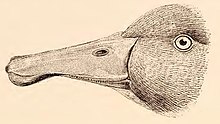

The blue duck is 53 cm (21 in) long and varies in weight by sex. Females are smaller than males, weighing 680–870 g (24–31 oz), whereas the males weigh 820–970 grams (29–34 oz).[16] The plumage is a dark slate-grey with a greenish sheen on the head, a chestnut-flecked breast. The outer secondaries are tipped with white and the inner ones have black margins. The plumage of the two sexes are mostly the same, although the female has slightly less chestnut in the chest.[17] The pinkish-white bill has fleshy flaps of skin hanging from the sides of its tip. The beak is green at hatching and develops its final colour eight hours later .

Song

[edit]The male's call is a high-pitched whistle.[13][14] The female's call is a rattling growl or low-pitched grating notes.[13][14][18]

Behaviour

[edit]This species is an endemic resident breeder in New Zealand, nesting in hollow logs, small caves and other sheltered spots. It is a rare duck, holding territories on fast flowing mountain rivers. It is a powerful swimmer even in strong currents, but is reluctant to fly. It is difficult to find, but not particularly wary when located.

Diet

[edit]The blue duck feeds almost entirely on aquatic invertebrate larvae. A study of blue ducks on the Manganuiateao River in the central North Island found the most common prey items were Chironomidae (midge) and cased caddisfly larvae, although cased caddisfly were less preferred and were only consumed so much because of their abundance. Hydrobiosidae (free-living caddisfly) and Aphrophila neozelandica (crane fly) larvae were also frequently eaten. Other prey included mayfly, Aoteapysche (net-building caddis) and stonefly larvae.[19] The blue duck on occasion take berries and the fruits of shrubs.[1]

Breeding

[edit]

Blue ducks nest between August and October, laying 4–9 creamy white eggs. The female incubates the eggs for 31 to 32 days and chicks can fly when about 70 days old.[16]

Nesting and egg incubation of four to seven eggs is undertaken by the female while the male stands guard. Nests are shallow, twig, grass and down-lined scrapes in caves, under river-side vegetation or in log-jams, and are therefore very prone to spring floods. For this, and other reasons, their breeding success is extremely variable from one year to the next.[20]

Captivity

[edit]

Captive North Island whio are held and bred on both main islands of New Zealand, but the progeny are returned to their respective island. South Island whio are held and bred in captivity on the South Island only. All captives are kept by approved and permitted zoological and wildlife facilities as part of the national recovery plan. As part of this current ten-year plan (2009–2019) is the WHIONE programme which works with specially trained nose dogs to locate nests. The eggs are removed, and the ducklings hatched and raised in captivity. Later they are conditioned for coordinated release.

Blue ducks were presented to the International Waterfowl Association in the UK in the 1970s along with New Zealand shovelers, New Zealand scaup, and brown teal by The Wildlife Service of New Zealand. The species was maintained in the UK until at least 2012[21] before dying out; efforts to create the only captive breeding population outside of New Zealand with these ducks ultimately failed when the last two male ducks formed a same-sex relationship with each other instead of with the female that was assigned to them.[22] They have not been known to be exported and maintained anywhere else internationally.[23]

Status

[edit]The blue duck is classified as Endangered by the IUCN due to its highly fragmented and shrinking population, and it is listed as Nationally Endangered in the New Zealand Threat Classification System. A 2010 census estimated a total population size of 2,500–3,000 individuals, with a maximum of 1,200 pairs.[1]

The blue duck is a very localised species now threatened by predation from introduced mammals such as stoats, competition for its invertebrate food with introduced trout, and damming of mountain rivers for hydroelectric schemes. Early recovery efforts by scientists, field workers and volunteers have been summarised in a project sponsored by Genesis Energy, the Central North Island Blue Duck Charitable Conservation Trust and the Royal Forest and Bird Protection Society in 2006.[24] In 2009 the New Zealand Department of Conservation started a ten-year recovery programme to protect the species at eight sites using predator control and then re-establish populations throughout their entire former range.[25] Female whio are especially vulnerable to stoats while nesting, and some populations are now 70 percent male.[26] In one study area, clutches of eggs lasted an average of nine days before being destroyed by stoats, and the one brood that hatched was killed the next day.[26]

In 2011 the New Zealand Department of Conservation and Genesis Energy started the Whio Forever Project, a five-year management programme for whio. It will enable the implementation of a national recovery plan that will double the number of fully operational secure blue duck breeding sites throughout New Zealand, and boost pest control efforts.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c BirdLife International. (2022). "Hymenolaimus malacorhynchos". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2022: e.T22680121A214275489. Retrieved 5 June 2023.

- ^ Cook, James; Furneaux, Tobias (1777). A Voyage Towards the South Pole, and Round the World : Performed in His Majesty's ships the Resolution and Adventure, in the Years 1772, 1773, 1774, and 1775. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). London: W. Strahan and T. Cadell. pp. 72, 97.

- ^ Forster, Georg (1777). A Voyage Round the World, in His Britannic Majesty's Sloop, Resolution, Commanded by Capt. James Cook, During the Years 1772, 3, 4, and 5. Vol. 1. London: B. White, P. Elmsly, G. Robinson. p. 157.

- ^ Latham, John (1785). A General Synopsis of Birds. Vol. 2, Part 2. London: Printed for Leigh and Sotheby. p. 522. Archived from the original on 1 July 2022. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ Gmelin, Johann Friedrich (1789). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae : secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. 1, Part 2 (13th ed.). Lipsiae [Leipzig]: Georg. Emanuel. Beer. p. 526. Archived from the original on 29 June 2022. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ Gray, George Robert (1843). "Some remarks on the soft-billed duck of Latham". Annals and Magazine of Natural History. 11 (71): 369–372 [370]. doi:10.1080/03745484309445317. Archived from the original on 20 June 2022. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ a b c Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (January 2022). "Screamers, ducks, geese & swans". IOC World Bird List Version 12.1. International Ornithologists' Union. Archived from the original on 1 October 2017. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ Jobling, James A. (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 198, 239. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^ "Habitat loss > Hymenolaimus malacorhynchos (blue duck, whio) > Taxonomy". NHM.ac.uk. Natural History Museum, London. Archived from the original on 14 August 2014. Retrieved 5 December 2014.

- ^ Howard, Richard; Moore, Alick (2013). A complete checklist of the birds of the world (4th ed.).

- ^ Kear, J. (2005). Bird families of the world: Ducks, geese and swans. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Livezey, Bradley C. (1986). "A phylogenetic analysis of recent anseriform genera using morphological characters" (PDF). Auk. 103 (4): 737–754. doi:10.1093/auk/103.4.737. JSTOR 4087184. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 February 2020. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- ^ a b c Lindsey, Terence; Morris, Rod (2011). Collins field guide to New Zealand wildlife. Auckland: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-1-86950-881-4. OCLC 776539108.

- ^ a b c d "Blue Duck". Archived from the original on 30 May 2022. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- ^ Robertson, B. C.; Paley, R.; Gemmell, N. J. (2003). Broad-scale genetic population structure in blue duck Hymenolaimus malacorhynchos. Pilot study of mitochondrial genetic variation (Report). DOC Science Internal Series. Vol. 112. New Zealand Department of Conservation. p. 12.

- ^ a b Marchant, S.; Higgins, P.G., eds. (1990). "Hymenolaimus malacorhynchos Blue Duck" (PDF). Handbook of Australian, New Zealand & Antarctic Birds. Volume 1: Ratites to ducks; Part B, Australian pelican to ducks. Melbourne, Victoria: Oxford University Press. pp. 1255–1260. ISBN 978-0-19-553068-1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 August 2022. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ Carboneras, K.; Kirwan, G.M. (2017). del Hoyo, Josep; Elliott, Andrew; Sargatal, Jordi; Christie, David A.; de Juana, Eduardo (eds.). "Blue Duck (Hymenolaimus malacorhynchos)". Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Barcelona, Spain: Lynx Edicions. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- ^ Madge, Steve; Burn, Hilary (1987). Wildfowl: an identification guide to the ducks, geese and swans of the world. London: Christopher Helm. ISBN 978-0-7470-2201-5.

- ^ Veltman, C. J.; Collier, K. J.; Henderson, I. M.; Newton, L. (1995). "Foraging ecology of blue ducks Hymenolaimus malacorhynchos on a New Zealand river: implications for conservation". Biological Conservation. 74 (3): 187–194. Bibcode:1995BCons..74..187V. doi:10.1016/0006-3207(95)00029-4.

- ^ "Blue duck/whio". New Zealand Department of Conservation – Te Papa Atawhai. Archived from the original on 2 March 2015. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- ^ "Ducky companion saves blue Jerry from a lonely life". WWT.org.uk. Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust. 5 March 2012. Archived from the original on 9 December 2014. Retrieved 5 December 2014.

- ^ Lite, Jordan. "Gay ducks derail repopulation plan". Scientific American Blog Network. Archived from the original on 4 December 2021. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

- ^ "Blue Duck". British Waterfowl Association. Archived from the original on 5 March 2022. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ^ Young, David (2006). Whio : saving New Zealand's blue duck. Nelson, N.Z.: Craig Potton Publishing. ISBN 9781877333460. OCLC 166312805.

- ^ Glaser, Andrew; Andrew, Paul; Elliott, Graeme; Edge, Kerri-Anne (December 2010). Whio/blue duck (Hymenolaimus malacorhynchos) recovery plan 2009–2019 (PDF). Threatened Species Recovery Plan 62. Wellington, N.Z.: Department of Conservation. ISBN 978-0-478-14841-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- ^ a b Hansford, Dave (July–August 2018). "The first test". New Zealand Geographic. 152: 74–91. Archived from the original on 6 August 2018. Retrieved 5 August 2018.

Further reading

[edit]- Adams, J.; Cunningham, D.; Molloy, J.; Phillipson, S. (1997). "Blue duck (Whio) Hymenolaimus malacorhynchos recovery plan 1997–2007" (PDF). Wellington, New Zealand: Department of Conservation. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 October 2012. Retrieved 7 November 2007.

- Whitehead, A.; Edge, K.; Smart, A.; Hill, G.; Willans, M. (2008). "Large scale predator control improves the productivity of a rare New Zealand riverine duck". Biological Conservation. 141 (11): 2784–2794. Bibcode:2008BCons.141.2784W. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2008.08.013.

- Whitehead, A.; Elliott, G.; McIntosh, A. (2010). "Large-scale predator control increases population viability of a rare New Zealand riverine duck". Austral Ecology. 35 (7): 722–730. Bibcode:2010AusEc..35..722W. doi:10.1111/j.1442-9993.2009.02079.x.

External links

[edit]- ARKive: Images and movies of the Blue Duck (Hymenolaimus malacorhynchos)

- BirdLife Species Factsheet.

- Blue duck/Whio at the Department of Conservation

- TerraNature | New Zealand ecology – Blue duck (Whio)

- Blue Duck Project Charitable Trust

- Whio Forever Project

- Central North Island Blue Duck Trust Archived 16 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine