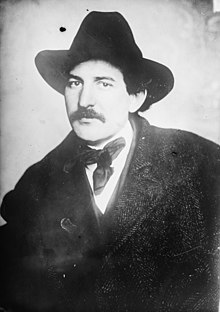

Ben Reitman

Ben Reitman | |

|---|---|

Ben Reitman | |

| Born | Ben Lewis Reitman 1879 |

| Died | 1943 (aged 63–64) |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation(s) | Physician, hobo |

| Known for | Lover of Emma Goldman |

| Notable work | Sister of the Road: The Autobiography of Boxcar Bertha (1937) |

| Spouse(s) | Mae Schwartz Anna Martindale[1] Rose Siegal Medina Rivets Oliver[2] |

| Partner(s) | Emma Goldman Eileen O'Connor[1] |

Ben Lewis Reitman M.D. (1879–1943) was an American anarchist and physician to the poor ("the hobo doctor"). He is best remembered today as one of radical Emma Goldman's lovers. Martin Scorsese's 1972 feature film Boxcar Bertha is based on Sister of the Road, one of Reitman's books.

Biography

[edit]Reitman was born in Saint Paul, Minnesota, to poor Russian Jewish immigrants in 1879, and grew up in Chicago. At the age of twelve, he became a hobo,[3] but returned to Chicago and worked in the Polyclinic Laboratory as a "laboratory boy".[4] In 1900, he entered the College of Physicians and Surgeons in Chicago, completing his medical studies in 1904. During this time he was briefly married; he and his wife had a daughter together.[4] His wife was Mae Schwartz, and their daughter was Jan Gay (born Helen Reitman), the author, nudism advocate, and founder of the nudist Out-of-Door Club at Highland, New York.[5][6][7]

He worked as a physician in Chicago, choosing to offer services to hobos, prostitutes, the poor, and other outcasts. Notably, he performed abortions, which were illegal at the time.[4] In 1907, Reitman became known as "King of the Hobos" when he opened a Chicago branch of the Hobo College, which became the largest of the International Brotherhood Welfare Association centers for migrant education, political organizing, and social services.[8]

His eyes were brown, large, and dreamy. His lips, disclosing beautiful teeth when he smiled, were full and passionate. He looked a handsome brute. His hands, narrow and white, exerted a peculiar fascination. His finger-nails, like his hair, seemed to be on strike against soap and brush. I could not take my eyes off his hands. A strange charm seemed to emanate from them, caressing and stirring... Emma Goldman on Reitman in Living My Life, Volume 1

Reitman met Emma Goldman in 1908, when he offered her use of the college's Hobo Hall for a speech, and the two began a love affair, which Goldman described as the "Great Grand Passion" of her life.[9] The two traveled together for almost eight years, working for the causes of birth control, free speech, worker's rights, and anarchism.

During this time, the couple became involved in the San Diego free speech fight in 1912–13. Reitman was kidnapped by a mob, severely beaten, tarred and feathered,[10] branded with "I.W.W.,"[9][11][12][13] and his rectum and testicles were abused.[14] Several years later, the couple were arrested in 1916 under the Comstock laws for advocating birth control, and Reitman served six months in prison.[15]

Both believed in free love, but Reitman's practice incited feelings of jealousy in Goldman.[16] He remarried when one of his lovers became pregnant; their son was born while he was in prison.[4] Goldman and Reitman ended their relationship in 1917, after Reitman was released from prison.[4]

Reitman returned to Chicago, ultimately working with the City of Chicago, establishing the Chicago Society for the Prevention of Venereal Disease in the 1930s.[4] His second wife died in 1930, and Reitman married a third time, to Rose Siegal.[4] Reitman later became seriously involved with Medina Oliver, and the couple had four daughters – Mecca, Medina, Victoria, and Olive.[4]

Reitman died in Chicago of a heart attack at the age of sixty-three. He was buried at the Waldheim Cemetery[17] (now Forest Home Cemetery), in Forest Park, Illinois.

Works by Reitman

[edit]- The Second Oldest Profession - A Study of the Prostitute's "Business Manager" (1931) (A sociological study of pimps)[18]

- Sister of the Road: The Autobiography of Boxcar Bertha (1937) (fiction)[19][20][21][22]

See also

[edit]- Boxcar Bertha, the Scorsese film loosely adapted from Reitman's novel "Sister of the Road"

- Birth control movement in the United States

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b "REVIEW: NO REGRETS". dwardmac.pitzer.edu. Retrieved 2020-05-17.

- ^ "Helen Reitman". Gay History Wiki. Retrieved 2020-05-17.

- ^ Patrick, Clinton (1987-02-01). "A REBEL OF MANY CAUSES". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-07-17.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Reitman profile, UIC.

- ^ "1932, Jan Gay, On Going Naked, Falstaff Pr,PRIVATE PRINT! LIM/NUMBERED/SIGNED!! | #1756939110". Worthpoint. Retrieved 2020-05-17.

- ^ "THE NUDIST Vol. 02, No. 06, August: (1933) | Alta-Glamour Inc". www.iberlibro.com. Retrieved 2020-05-17.

- ^ "THE NUDIST Vol. 02, No. 07, October [stated; otherwise identical to September issue]: (1933) | Alta-Glamour Inc". www.abebooks.co.uk. Retrieved 2020-05-17.

- ^ JWA "Women of Valor — Emma Goldman - Love & Sexuality - Ben Reitman", Jewish Women's Archive. Retrieved September 2, 2018.

- ^ a b Emma Goldman, Living My Life, Volume 1.

- ^ "REITMAN DESCRIBES HOW HE WAS TARRED; Emma Goldman's Manager Tells About Tortures Inflicted by Vigilantes on California Desert". The New York Times. 1912-05-17. p. 7. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-07-17.

- ^ John A. Farrell, Clarence Darrow: Attorney for the Damned, (Doubleday 2011), p. 243. ISBN 978-0-385-52258-8

- ^ "Free Speech in the Progressive Era | American Experience | PBS". www.pbs.org. Retrieved 2022-08-20.

- ^ "May 20, 1913: Emma Goldman returns". San Diego Union-Tribune. 2018-05-20. Retrieved 2022-08-20.

- ^ Smith, Jeff (July 4, 2012). "The Big Noise: The Free Speech Fight of 1912, Part Seven | San Diego Reader". San Diego Reader. Retrieved 2023-07-17.

- ^ Wexler, Intimate, pp. 211–215.

- ^ Wexler, Intimate, pp. 140–147.

- ^ Roth, Walter (2005-08-01). Looking Backward: True Stories from Chicago's Jewish Past. Chicago Review Press. ISBN 9780897338271. Retrieved 2020-05-17 – via Google Books.

- ^

- Anderson, Nels (September 1931). "Review of The Second Oldest Profession". American Journal of Sociology. 37 (2): 323. doi:10.1086/215696. ISSN 0002-9602. JSTOR 2766573. EBSCOhost 15466454.

- "Review of The Second Oldest Profession. A Study Of The Prostitute's Business Manager". The British Medical Journal. 2 (3951): 630. 1936. ISSN 0007-1447. JSTOR 25354062.

- Book Review Digest 1931

- ^ Boxcar Bertha: Tales spun from the hobo world The Portland Alliance, Ruth Kovacs, November 2002 issue

- ^ "Despite decades of scholarship claiming otherwise, Boxcar Bertha is not a real woman but an imagined representation of unconventional female life in the early twentieth century. In her unpublished dissertation, Martha Reis carefully documents the lives of the women who inspired Bertha’s character, including a female pickpocket, anarchist, and ex-patriot poet." Venturing More Than Others Have Dared: Representations of Class Mobility, Gender, and Alternative Communities in American Literature, 1840-1940; dissertation, Heather Joy Thompson-Gillis, MA, The Ohio State University 2012

- ^ Hidden histories, Ben Reitman and the "outcast" women behind Sister of the Road : the autobiography of Box-Car Bertha Martha Lynn Reis, dissertation, Ph. D. University of Minnesota 2000

- ^ Pfahlert, Jeanine (April 1, 2004). "Book Reviews (Rev. of Sister of the Road)". European Journal of American Culture. 23 (1): 6465. doi:10.1386/ejac.23.1.63/0. ISSN 1466-0407.

Works cited

[edit]- Frank O. Beck, Hobohemia: Emma Goldman, Lucy Parsons, Ben Reitman & Other Agitators & Outsiders In 1920s/30s Chicago (Charles H. Kerr Press, 2000, ISBN 978-0-88286-251-4 (description)

- Roger Bruns, The Damndest Radical: The Life and World of Ben Reitman, Chicago's Celebrated Social Reformer, Hobo King, and Whorehouse Physician (University of Illinois, 2001)

- Mecca Reitman Carpenter, No Regrets: Dr. Ben Reitman and the Women Who Loved Him (SouthSide Press, 1996) (biographical memoir by Reitman's daughter)

- Emma Goldman, Living My Life (1931)

- University of Illinois at Chicago, University Library, "Ben Reitman Biographical Sketch", Reitman papers.

- Alice Wexler, Emma Goldman: An Intimate Life. New York: Pantheon Books, 1984. ISBN 0-394-52975-8. Republished as Emma Goldman in America. Boston: Beacon Press, 1984. ISBN 0-8070-7003-3.

- Tim Cresswell, The Tramp in America. London: Reaktion Books, 2001. ISBN 1-86189-069-9.

Further reading

[edit]- Geis, Gilbert (September 2008). "Ben L. Reitman, MD: colorful critical criminologist". Contemporary Justice Review. 11 (3): 271–285. doi:10.1080/10282580802295534. ISSN 1028-2580. S2CID 143500946. EBSCOhost 34036487.

- Pateman, Barry (2002). "Afterword". Sister of the Road: The Autobiography of Boxcar Bertha. AK Press/Nabat. ISBN 978-1-902593-03-6. OCLC 48534916.

- Sante, Luc (April 27, 1989). "On the Bum". The New York Review of Books. ISSN 0028-7504.

External links

[edit]- The More Things Stay the Same (Ben Reitman Documentary)

- Emma Goldman PBS American Experience

- Emma Goldman Ephéméride Anarchiste

- Ben Reitman Anarchist Encyclopedia

- "Ben Reitman". Find a Grave. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- Ben Lewis Reitman (letters and papers from 1907 to 1989), University of Illinois at Chicago

- "Ben L. Reitman papers". Special Collections of the University of Illinois Chicago Library.

- 1879 births

- 1943 deaths

- American anarchists

- American primary care physicians

- Burials at Forest Home Cemetery, Chicago

- People convicted under the Comstock laws

- People from Saint Paul, Minnesota

- American people of Russian-Jewish descent

- American abortion providers

- Anarcho-communists

- Emma Goldman

- American torture victims