Butcher Store in Schäftlarn on the Isar

| Butcher Store in Schäftlarn on the Isar | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Lovis Corinth |

| Year | 1897 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 69 cm × 87 cm (27 in × 34 in) |

| Location | Kunsthalle Bremen, Bremen |

Butcher Store in Schäftlarn on the Isar (German: Schlachterladen in Schäftlarn an der Isar) is a painting by the German painter Lovis Corinth from 1897. The picture shows a scene from the store of a slaughterhouse in Schäftlarn near Munich. It is held in the Kunsthalle Bremen.

The painting belongs to a series of genre paintings by Corinth that explore the theme of slaughterhouses and butcher stores, which appear several times in his complete works. These butcher and meat drawings are widely seen by art historians as a means for Corinth to process his childhood memories as the son of a tanner, often drawing comparisons and connections to the artist's nude paintings.

Description[edit]

The painting is an oil painting on canvas. It is 69 cm high, 87 ;cm wide, and signed in black paint on the upper right edge of the picture in two lines: "Lovis Corinth 1897".[1]

The image depicts a scene in a butcher shop. A smiling young man stands in a room with a bowl of meat pieces in the foreground, in front of a counter with a meat scale hanging from it. Several slaughtered pigs, as well as various chunks of flesh and animal heads, are hung on the bar and on the wall. The background portrays the interior of a butcher shop, with shades of green and brown dominating the palette. A window in the back lets in natural light, revealing foliage behind it. The painting is divided into two equal halves by two arched bays. The slaughtered animals hung on the wall, as well as the chunks of meat on the counter and in the young man's bowl, appear to be illuminated by another light source in the front.

Horst Uhr's interpretation suggests that the dark-toned background creates a striking contrast with the vibrant, multi-colored pieces of meat displayed on the counter and wall. Through the glossy sheen of the paint, the artist achieves a greasy texture on the flesh.[2] Furthermore, the existence of vaults visually balances the painting's composition, effectively dividing the artwork.[2][3] This interplay between the red pieces of meat and the rack adds to the overall balance of the scene. Lucia Klee-Beck emphasizes the "strict composition of the painting" with the centrally placed table that symmetrically divides the field of view into a back wall area with whole animal carcasses hanging from it and a front counter area with pre-cut chunks of meat. The foreshortening of perspective is reinforced by the staggering of the pieces according to their diminishing size from right to left toward the window.[4] Hans-Jürgen Imiela characterizes the painting as a glimpse into a low-vaulted room with eviscerated animals and carcass fragments in the front. In this front area, a boy stands, gazing outward, while holding a trough filled with meat pieces. Notably, the illumination from the window in the background plays a significant role.[5] It creates a distinct backlight effect, further enhancing the overall impact of the image.[5]

Origin and classification in the work of Corinth[edit]

Chronological classification[edit]

At the end of his Munich studies, Lovis Corinth painted the picture Schlachterladen in Schäftlarn an der Isar in 1897. Corinth studied painting in Königsberg and Munich before spending almost three years between 1884 and 1887 at the Académie Julian in Paris, where he was primarily influenced by the neoclassical works of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and by the Impressionism and Pointillism of contemporary French art. William Adolphe Bouguereau and Joseph Nicolas Robert-Fleury were his professors at the time. Corinth was an active participant in the Paris art scene throughout his tenure there, visiting the Salon de Paris, the Paris galleries, and also the museums such as the Louvre. In 1887 Corinth returned to Munich, inspired by the work Die Wilderer (The Poachers) by Wilhelm Leibl exhibited at the Kunstsalon Georges Petit.[6]

Corinth produced one of his best-known works in Munich, Self-Portrait with Skeleton in 1896, and with other works from this period, Corinth established himself in the local art scene in Munich as well as nationally.

At this time, one of Corinth's focuses was on the nude scenes in historical contexts. Thus, in the same year as Schlachterladen in Schäftlarn an der Isar, he also created paintings such as die Versuchung des heiligen Antonius ("The Temptation of St. Anthony"), Susanna und die beiden Alten ("Susanna and the Two Old Men"), and Die Hexen ("The Witches"), as well as portraits such as the portrait of the painter Otto Eckmann.

Corinth experienced a significant breakthrough during this period with his renowned work Salome, completed in 1900. In a historical context, this painting depicts Salome, the daughter of Herodias, holding the severed head of John the Baptist. Inspired by Oscar Wilde's literary model, the painting received immense recognition. However, as it was not permitted for display at the Munich Secession, Corinth entrusted the artwork to Walter Leistikow in Berlin, who accepted it for exhibition at the Berlin Secession. The triumph of Salome prompted Corinth to relocate to Berlin shortly thereafter, seeking new opportunities and inspiration in the city's vibrant art scene.[6]

Content[edit]

Schlachterladen in Schäftlarn an der Isar is a highly recognized genre painting by Corinth, focusing on the theme of slaughter. It is among his most renowned works in this genre. Corinth explored this theme in a total of 14 paintings, along with numerous sketches and prints. One such example is Geschlachtetes Schwein ("Slaughtered Pig") from 1906, which can be found in the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.[7]

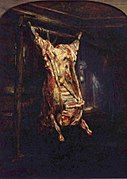

The representation and depiction of slaughterhouse scenes and images of meat can be traced back to the early origins of painting. This can be seen in the hunting scenes depicted in cave paintings. Some of the earliest surviving depictions of domestic animal slaughter can be found in ancient Egypt, such as the relief carvings in the Mastaba of Ti,[8] which date back to r 2400 roughly BC during the 5th Dynasty of the Old Kingdom. This theme continued to be explored in various cultures throughout history. Examples include its presence in Greek vase paintings,[9] Roman Empire reliefs, and even up to modern times.[10] Long before Corinth, the idea was picked up and depicted in Baroque and Rococo paintings, especially in Italian and Dutch art. During the 16th century, painters like Pieter Aertsen from the Netherlands and Annibale Carracci from Italy created numerous artworks featuring meat pieces and animal halves displayed in butcher shops. Rembrandt van Rijn, a renowned Dutch artist, also explored this theme. His well-known painting, Geschlachteter Ochse ("Slaughtered Ox") from 1655, is housed in the Louvre Museum in Paris. Corinth was familiar with Rembrandt's work and followed in the footsteps of this art historical tradition, influenced by his time in Paris. Furthermore, Corinth's contemporaries, including François Bonvin with his Das Schwein -Hof des Schlachters ("The Pig-The Butcher's Farm") from 1874, Max Liebermann with his Schlächterladen in Dordrecht ("Butcher store in Dordrecht") from 1877, and Max Slevogt with Geschlachtetes Schwein ("Slaughtered pig") from 1906, also tackled the theme of slaughterhouse scenes, further contributing to its artistic exploration during that period.[11]

Corinth's childhood connection to the butcher's trade led him to engage more profoundly and extensively with the subject matter. Gert von der Osten notes that Corinth had already completed his cattle and butcher scenes before 1890.[12] In 1892, he began painting the first series of slaughterhouse scenes, including Schlachterei ("Butcher Shop"),[13] Kühe im Stall ("Cows in the Stable"),[14] and the initial version of Geschlachteter Ochse ("Slaughtered Ox").[15]

In 1893, Corinth created one of his better-known paintings, Im Schlachthaus ("In the Slaughterhouse").[16] This painting, along with Schlachthauszene ("Slaughterhouse Scene") from the same year, portrays an animal slaughter taking place in a dimly lit cellar room.[17] The scene depicts five butchers engaged in the process of disemboweling and skinning a slaughtered animal. Four of the butchers are aggressively working on the carcass using various tools, while another stands behind a bowl filled with offal, rolling up his sleeves. The painting skillfully captures the atmosphere and intensity of skinning a slaughtered ox.[18] Andrea Bärnreuther observes that the painting "celebrates the drama of the antagonism between flesh and death." She suggests that a "struggle on two fronts" is occurring within the artwork. On one side, the group of journeymen butchers in the foreground are depicted working their way into the picture, and the animal, from the front right. On the other side, there is a sense of tension created by the butcher positioned behind the animal on the left. In her description, Bärnreuther highlights the contrasting movements depicted in these scenes, which emerge through the play of light. The light, entering through a background window, emits from the "escaping life," according to her interpretation, and symbolically "unifies the victim and perpetrator in a shared act."[19] The animal body serves as the focal point of the image and the action taking place. Additionally, the presence of bloody and slippery pools on the slaughterhouse floor contributes to a "sultry atmosphere" that evokes sensations beyond mere visual perception.[20]

Friedrich Gross defines the room in the painting as a "cavernous cellar space." The presence of a bright green light, filtered through foliage and cast through a barred window, emphasizes the prison-like appearance of the scene. The use of wild and disruptive brushstrokes further highlights the violent nature of the slaughter.[19] The use of white and red brushstrokes is not confined to specific areas but spreads indiscriminately across the carcass, the butchers, the flesh, the skin, and even the walls.[21][22] Till Schoofs underlined the painting's distinction from other works of the time: "The energetic broad brushstroke and sketchy character of the painting differ from Corinth's contemporaneous academic paintings and must have been created in an almost feverish flurry of movement."[23] Geschlachtete Kälber ("Slaughtered Calves"), painted in 1896, focuses once again on the depiction of suspended carcasses of slaughtered animals within the slaughterhouse setting. On the other hand, Schlachterladen in Schäftlarn an der Isar approaches the butcher scene from a different perspective. It presents viewers with a glimpse into the typical atmosphere of a butcher's store during the turn of the century.[24]

According to Alfred Rohde's 1941 assessment, Schlachterladen in Schäftlarn an der Isar represents an achievement in the ongoing exploration of the slaughterhouse theme.[18][25] Meanwhile, Georg Biermann's 1913 description characterizes the painting as artistically exquisite, with a rich and intense color palette consisting of delicate white and red tones.[26] In this particular artwork, the emphasis shifts away from the act of slaughtering and cutting. Instead, a friendly-looking apprentice butcher stands in front of the slaughtered animals in the image. The butcher is shown offering fresh meat to the viewer.[27] According to Lucia Klee-Beck, Corinth also attempted to "subtly illustrate the pre-industrial self-image of such establishments and the artisanal self-confidence of their operators" in the painting.[4] Bärnreuther's analysis states that Schlachterladen in Schäftlarn an der Isar portrays a shift in tone compared to the intense excitement of slaughter depicted in Im Schlachthaus ("In the Slaughterhouse") from 1893.[3] In this painting, the focus has transitioned to a more composed and contemplative gaze, where the viewers can indulge in the visual feast of the slaughtered meat. Horst Uhr perceives the painting as possessing a controlled and logical structure, characterized by a less aggressive tone compared to previous works.[2] Additionally, Zimmermann highlights the presence of a boy with a "red-tinged smile," potentially adding an element of intrigue and curiosity to the scene.[22] In contrast to Max Liebermann's 1877 Schlächterladen in Dordrecht ("Butcher's Shop in Dordrecht"), Corinth's depiction of the meat pieces in Schlachterladen in Schäftlarn an der Isar conveys a sense of greater realism and representation.[2]

Gert von der Osten described this journeyman butcher as "the grandest butcher's portrayal."[12]

"The journeyman in the butcher's store is most grandly captured: the impulsive face with the ruffled hair is distorted into a narrow grin and glaringly split in the slant between highlight and shadow. A demon figure on the threshold of the century, which in its deepest abysses will also estimate man himself according to his mere living weight – and yet only a butcher's journeyman of Bavarian-rural kind, so self-evident that of all that certainly only the painter, and even he hardly suspecting, writes something on the canvas."

— Gert von der Osten, 1955

Unlike the previous versions, Friedrich Gross portrays the scene in the butcher's store in a warm and amiable manner. He describes the goods in the store gleaming in the sunlight and highlights the presence of a laughing butcher's boy holding a bowl of succulent beef pieces, seemingly presenting them for sale. This depiction evokes a friendly and inviting atmosphere within the butcher's shop.[19] It is worth noting that in 1892, Corinth merged the imagery of the slaughterhouse scene with that of the livestock stables. This combination resulted in the inclusion of stable interiors within the painting, which was completed in 1897.[28]

Even after the 1890s, Corinth painted several pictures of slaughterhouses or parts of meat. In 1905, he created another and better-known rendition of the Geschlachteter Ochse ("Slaughtered ox"),[29] which Zimmermann describes as the most opulent painting of the slaughterhouse pictures.[21][22]As in Rembrandt's model, a headless ox suspended by its hind legs and disemboweled is depicted filling the picture. Half of the hide has been removed, framing the red glazing flesh with the clear white and pearly fat depicted. The butcher and another body are inconspicuously displayed in the background.[21]

In 1906, Corinth painted several halves of pigs hanging on the wall in a butcher's shop, and in 1913,[30] in a painting also named Fleischerladen ("Butcher's shop"),[31] he depicted the pieces of meat hanging on the wall as "amorphous chunks of meat."[12]

Around 1925, the year of Corinth's death, the White Russian painter Chaim Soutine in Paris took up the theme of slaughterhouse scenes again, depicting them in an expressionist manner with red and yellow animals and blue "killing apparatus." Another artist was Norbert Tadeusz, who in 1983 painted a hanging bovine and in a study for his large-scale Vorhölle – Abnahme (Limbo – decrease) gave a slaughtered animal body the shape of a woman. The hanging animals also find a place in his Volto Santo.[32]

Interpretation and reception[edit]

The interpretations for Schlachterladen in Schäftlarn an der Isar refer to various aspects, which several critics associate with the entire series of Corinth's slaughterhouse paintings. The painting is usually considered together with Im Schlachthaus ("In the Slaughterhouse") from 1893 and Geschlachteter Ochse ("Slaughtered Ox") from 1905 as the central work of this type. The processing of childhood memories, the fascination with the act of slaughtering itself, the sensuality of meat, and thus also the transference of Fleischeslust ("Meat lust") are named as essential aspects of interpretation.

Processing childhood memories[edit]

Lovis Corinth, the son of a tanner, had to confront the memories of his childhood dealing with slaughtered animals and his father's processing of their skins.[12] In his autobiographical writings, he described these memories in various ways, such as recalling the butchers who came to the house to negotiate the freshly stripped hides from cows and fat pigs.[33]

"The slaughtering with the big animals was different; the first stage I could not see – I hid. But then later I no longer saw the creature from before, and I delighted in it. Many a person would probably scold me when I poked my eyes out of the pig's head and did similar inquisitive things; on the other hand, the cow, when it hung in the attic, was always regarded with a certain reverence and sadness."

— Lovis Corinth, "Künstlers Erdenwallen," 1920

Later, while studying painting at the Königsberg Academy of Arts, he got the opportunity to draw and paint in a slaughterhouse through a brother-in-law who worked as a butcher. He described this in detail in his autobiographies and especially in the Legends from the Artist's Life, in which he portrayed himself in the guise of Heinrich the painter. Especially in this work Corinth described in detail the scene of the slaughterhouse and the slaughter of an ox, where "Heinrich" was present and where he could paint it:[34]

"White steam smoked from the broken bodies of the animals. Viscera, red, purple and pearly, hung from iron pillars. Heinrich wanted to paint all this. Many a time he was rudely pushed aside when carts, loaded with refuse and blood-soaked hides, were pushed hard past him. He paid no attention to this; he did not hear the cracking blows of the axes, the tumbling of the animals in the fervor of the work."

— Lovis Corinth, Legends from the Artist's Life, 1918

In 1996, Jill Lloyd analyzed Lovis Corinth's processing of his childhood memories and his choice of subject matter, including the slaughterhouse paintings and other motifs. Lloyd suggested that these artistic expressions could be a way for Corinth to confront and process childhood trauma. From her perspective, the slaughterhouse scenes evoke a sense of intense drama and energy.[27] Lloyd describes how the presence of blood streaming down large carcasses hanging from the ceiling seemed to provoke a primal and almost sexual excitement, enhancing the liveliness of these paintings. The intensity of Corinth's childhood memories adds an additional layer to these works.[27]

Michael F. Zimmermann provides an alternative interpretation of Lovis Corinth's descriptions, considering them as an "autobiographical myth" or a "legend." According to Zimmermann, Corinth creates a narrative that brings his life closer to the reader while simultaneously distancing it.[21][22] The contrasting elements of the butcher's shop and the studio, blood-soaked flesh, and sensuous skin serve as the pole between which Corinth constructs his pictorial narrative. Frédéric Bussmann, in his analysis of Corinth's painting Geschlachteter Ochse, similarly emphasizes that while the subject matter may have been influenced by Corinth's memories of childhood and youth, he did not consciously translate traumatizing memories into his art.[21] Instead, Bussmann suggests that Corinth was captivated by the allure of the flesh, focusing on its sensual qualities rather than the traumatic aspects. This perspective is also reflected in the representation of legends from Corinth's life, as noted by Schoofs.[11]

The act of slaughter and the desire for meat[edit]

Imiela's interpretation of Lovis Corinth's painting Schlachterladen in Schäftlarn an der Isar explores a borderline position. According to Imiela, the use of backlighting in the painting creates a frightening alteration of both animal and human existence.[5] The youngster and the beef hanging on the walls are described as acquiring a similar quality, blurring the boundaries between them.[5] Imiela suggests that Corinth did not experiment with such boundary blurring in his other works. Imiela also wonders if the scales hanging in the background behind the boy allude to a balancing act, adding a death reference and vanitas motif to the painting. This representation draws a parallel to Corinth's "Self-Portrait with Skeleton," where the vanitas theme is explicitly present. On the other hand, Lucia Blee-Beck notes that the vibrant red and green hues create a loosened or relaxed mood, contrasting with the vanitas concept.[4]

According to Gert von der Osten, "killing and being destroyed" as well as the "pale white fat and the dead red of life of the broken open animals" was for Corinth at this time "above all a feast".[12] Friedrich Gross relates this fascination with the theme of slaughter to the "fundamental destructive appropriation by man" and a "predatory lust and horror of the dismemberment of the living." In the foreword to the exhibition catalog of the Berlin Secession of 1918, art historian Julius Meier-Graefe went a step further and explicitly transferred the act of slaughter to Corinth's painting:[35]

"Sometimes, and especially in Berlin, he felt an earthly pleasure in front of the easel like the butcher in front of the cattle... The human in art. He slaughtered while he painted."

— Julius Meier-Graefe, 1918

This fascination with the act of slaughter and the pleasure of depicting the flesh is also described by other art historians. In the case of Geschlachteter Ochse ("Slaughtered ox"), Bussmann wrote of the "elaboration of sensuous flesh" and goes on to describe, "Corinth paints the carcass with sweeping strokes, circling the masses of flesh and caressing them almost tenderly with his brush."[11]

The sensuality of the slaughterhouse scenes and relation to the nude paintings[edit]

According to Gross's analysis, the slaughterhouse scenes in Lovis Corinth's work exhibit a strong sense of permissive sensuality. This quality is particularly evident in the painting Im Schlachthaus from 1893 and can be seen in relation to other works by Corinth, including his depictions of nudes and historical subjects.[32] Schlachterladen in Schäftlarn an der Isar, is less dramatic but still carries a sensual appeal. Gross suggests that the painting evokes a sense of simplicity, abundance, and pleasurable enjoyment. However, the presence of dull grays and dark colors in the artwork limits this permissive sensuality.[32]

Many authors have drawn a direct link between Lovis Corinth's butcher and meat pictures and his well-known nude paintings. Both kinds of art are associated with a sensuality that connects these motifs together. In this regard, Corinth has often been compared to Baroque painters such as Peter Paul Rubens and Jacob Jordaens. Jill Lloyd specifically relates the depiction of dead animal bodies in Corinth's paintings, which are brought to life through the virtuosity and sensuality of his painting, to the portrayal of women in his nude paintings.[19][36] She notes that Corinth treats both subjects as "breathing close" rather than as still lives.[27]

According to Zimmermann, there is a clear relationship between Lovis Corinth's portrayal of slaughterhouse scenes and his interest in depicting naked bodies and the embodiment of flesh, specifically the color and texture of the skin, in his work. Zimmermann places these depictions primarily in the context of Corinth's work such as the painting "Innocentia" from 1890, as well as other works where Corinth brings together female nudes, some of whom grab their breasts, highlighting the palpable softness of the body.[21][22] Other paintings he lists in this context include Die Hexen ("The Witches") (1897), Der Harem ("The Harem") (1904), and Die Waffen des Mars ("The Arms of Mars") (1910).[21][22] Outside of historical depictions, naked people are associated with battle paintings, such as the 1908 painting Die Nacktheit ("The Nudity"), which matches Geschlachteter Ochse ("Slaughtered ox") and depicts Corinth's wife Charlotte Berend-Corinth together with their twice-painted son Thomas. Zimmermann directly compares the coloring of his wife's body with Geschlachteter Ochse: "The skin is repeatedly suffused with red as if of exuberant vitality, but the swellings shimmer like pearly white. One could not have come closer to the tones of the ox in nude painting."[22]

Zimmermann comes to the following conclusion on the treatment of the subject of flesh and the relationship between Corinth's images of the body and nude paintings:[22]

"More than any other artist, Corinth combines his sensitivity to the incarnate, to naked living flesh without a covering, with a fascination for dead flesh. In his painting he encounters the model with an eroticism into which violence is mixed. Painting appears as an act that is always also violent, as an intrusion into the intimacy of the other that is always also inadmissible."

— Matthias F. Zimmermann, 2008

Exhibitions and provenance[edit]

The painting Schlachterladen in Schäftlarn an der Isar was created by Lovis Corinth in 1897 towards the end of his studies in Munich. It was formerly owned by Ernst Zaeslein, a Berlin-based art dealer and collector. In 1913, the painting was acquired by the Kunsthalle Bremen and became part of their collection (Inv. No. 347 – 1913/3).[37] Gustav Pauli, the director of the Kunsthalle Bremen at the time, was actively building a collection of contemporary art. Similar to Hugo von Tschudi at the National Gallery in Berlin, Gustav Pauli sought to acquire works by notable artists, including Paula Modersohn-Becker and French and German Impressionists. The collection included significant paintings such as Claude Monet's "Camille im grünen Kleid "(Camille in green dress), Édouard Manet's, Zacharie Astruc, as well as works by Gustave Courbet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Camille Pissarro, Max Liebermann, and Max Slevogt. In 1911, Kunsthalle Bremen's purchase of Vincent van Gogh's Mohnfeldes ("Poppy Field") sparked the Bremen artist dispute, which caused a heated debate among painters and individuals in the German art world. The controversy revolved around the museum's acquisition of modern artworks and its impact on traditional artistic practices. As part of their acquisitions, the Kunsthalle Bremen also included several paintings by Lovis Corinth, among other artists.[38]

Schlachterladen in Schäftlarn an der Isar is currently displayed in the permanent exhibition of the Kunsthalle Bremen. Over the years, it has also been showcased in numerous national and international exhibitions, particularly in the post-World War II period. According to Charlotte Berend-Corinth's catalog raisonné, the painting was featured in an exhibition at the Landesmuseum Hannover in 1950 and at the Museum zu Allerheiligen in Schaffhausen in 1955. In 1958, on the occasion of Lovis Corinth's 100th birthday, the painting was exhibited at the Old National Gallery in Berlin, the Kunsthalle Bremen, and the Kunstverein Hannover. Schlachterladen in Schäftlarn an der Isar continued to be exhibited in various locations and prestigious institutions throughout the years. In 1960, it was displayed at the Lentos Art Museum Linz. In 1975, it had its first exhibition in the United States at the Gallery of Modern Art in New York City. The painting was also showcased at the Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus in Munich in 1975 and at the Kunsthalle in Cologne in 1976.[39]

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City included the painting as part of the exhibition "German Masters of the Nineteenth Century" in 1981. It was also featured in exhibitions at the Museum Folkwang in Essen in 1985/1986, the Austria Kunstforum in Vienna 1992, and the Niedersächsisches Landesmuseum in Hannover in 1992/1993.[1]

In more recent years, Schlachterladen in Schäftlarn an der Isar was part of the exhibition "Augenschmaus – Vom Essen im Stillleben" at the Bank Austria Kunstforum in Vienna in 2010.[40] It was also included in the exhibition "Lovis Corinth – Das Leben ein Fest! (Life, a celebration)" at the Belvedere Palace in Vienna and the Modern Gallery of the Saarlandmuseum in Saarbrucken from 2021 to 2022.[4]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Schlachterladen in Schäftlarn an der Isar, 1897 In: Charlotte Berend-Corinth: Lovis Corinth: Die Gemälde. Neu bearbeitet von Béatrice Hernad. Bruckmann Verlag, München 1992; BC 147. 1992. p. 75. ISBN 3-7654-2566-4.

- ^ a b c d Horst Uhr. Lovis Corinth. University of California Press 1990. p. 107.

- ^ a b Andrea Bärnreuther (1996). Schlachterladen in Schäftlarn an der Isar, 1897, In: Peter-Klaus Schuster, Christoph Vitali, Barbara Butts (Hrsg.): Lovis Corinth. Prestel München 1996. p. 131. ISBN 3-7913-1645-1.

- ^ a b c d Lucia Klee-Beck (2021). chlachterladen in Schäftlarn an der Isar, 1897. In: Lovis Corinth – Das Leben ein Fest! / Life, a celebration! Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther und Franz König, Köln 2021. pp. 170–171. ISBN 978-3-96098-967-7.

- ^ a b c d Hans-Jürgen Imiela (1992). Einführung.. In: Charlotte Berend-Corinth: Lovis Corinth: Die Gemälde. Neu bearbeitet von Béatrice Hernad. Bruckmann Verlag, München 1992. p. 23. ISBN 3-7654-2566-4.

- ^ a b Zdenek Felix. Der Werdegang eines Außenseiters. In: Zdenek Felix (Hrsg.): Lovis Corinth 1858–1925. Publikation zur Ausstellung im Folkwang Museum Essen (10. November 1985 – 12. Januar 1986) und in der Kunsthalle der Hypno-Kulturstiftung München (24. Januar – 30. März 1986), DuMont Buchverlag, Köln 1985. pp. 17–18. ISBN 3-7701-1803-0.

- ^ Barbara Butts (1996). Geschlachtetes Schwein In: Peter-Klaus Schuster, Christoph Vitali, Barbara Butts (Hrsg.): Lovis Corinth. Prestel München 1996. pp. 336–337. ISBN 3-7913-1645-1.

- ^ Kurt Nagel; Benno P. Schlipf. Das Fleischerhandwerk in der bildenden Kunst. Kunstgeschichte des Fleischerhandwerks. Verlag C.F. Rees, Heidenheim 1982. p. 57.

- ^ Kurt Nagel, Benno P. Schlipf: Das Fleischerhandwerk in der bildenden Kunst. Kunstgeschichte des Fleischerhandwerks. Verlag C.F. Rees, Heidenheim 1982; pp. 58–59.

- ^ Kurt Nagel, Benno P. Schlipf: Das Fleischerhandwerk in der bildenden Kunst. Kunstgeschichte des Fleischerhandwerks. Verlag C.F. Rees, Heidenheim 1982; pp. 59–61.

- ^ a b c Frédéric Bussmann. Geschlachteter Ochse, 1905. In: Ulrike Lorenz, Marie-Amélie zu Salm-Salm, Hans-Werner Schmidt: Lovis Corinth und die Geburt der Moderne Katalog anlässlich der Retrospektive zum 150. Geburtstag von Lovis Corinth (1858–1925) in Paris, Leipzig und Regensburg. Kerber Verlag, Bielefeld 2005. pp. 162–163. ISBN 978-3-86678-177-1.

- ^ a b c d e Gert von der Osten: Lovis Corinth. Verlag F. Bruckmann, München 1955; pp. 50–51.

- ^ Schlachterei, 1892. In: Charlotte Berend-Corinth: Lovis Corinth: Die Gemälde. Neu bearbeitet von Béatrice Hernad. Bruckmann Verlag, München 1992. 1992. p. 67. ISBN 3-7654-2566-4.

- ^ Kühe im Stall, 1892. In: Charlotte Berend-Corinth: Lovis Corinth: Die Gemälde. Neu bearbeitet von Béatrice Hernad. Bruckmann Verlag, München 1992. 1992. p. 67. ISBN 3-7654-2566-4.

- ^ Geschlachteter Ochse, 1892. In: Charlotte Berend-Corinth: Lovis Corinth. Die Gemälde. Neu bearbeitet von Béatrice Hernad. Bruckmann Verlag, München 1992. 1992. p. 68. ISBN 3-7654-2566-4.

- ^ Im Schlachthaus, 1893. In: Charlotte Berend-Corinth: Lovis Corinth: Die Gemälde. Neu bearbeitet von Béatrice Hernad. Bruckmann Verlag, München 1992. 1992. p. 69. ISBN 3-7654-2566-4.

- ^ Schlachthausszene, 1893. In: Charlotte Berend-Corinth: Lovis Corinth: Die Gemälde. Neu bearbeitet von Béatrice Hernad. Bruckmann Verlag, München 1992. 1992. ISBN 3-7654-2566-4.

- ^ a b Kurt Nagel, Benno P. Schlipf: Das Fleischerhandwerk in der bildenden Kunst. Kunstgeschichte des Fleischerhandwerks. Verlag C.F. Rees, Heidenheim 1982; pp. 122–123.

- ^ a b c d Friedrich Gross. Die Sinnlichkeit in der Malerei Corinths. In: Zdenek Felix (Hrsg.): Lovis Corinth 1858–1925. Publikation zur Ausstellung im Folkwang Museum Essen (10. November 1985 – 12. Januar 1986) und in der Kunsthalle der Hypno-Kulturstiftung München (24. Januar – 30. März 1986), DuMont Buchverlag, Köln 1985. p. 43. ISBN 3-7701-1803-0.

- ^ Andrea Bärnreuther (1996). lm Schlachthaus, 1893. In: Peter-Klaus Schuster, Christoph Vitali, Barbara Butts (Hrsg.): Lovis Corinth. Prestel München 1996. pp. 130–131. ISBN 3-7913-1645-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g Schlachthaus und Akt, Blut und Inkarnat. In: Michael F. Zimmermann: Lovis Corinth. Reihe Beck Wissen bsr 2509. C. H. Beck, München 2008. 2008. pp. 41–51. ISBN 978-3-406-56935-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Michael F. Zimmermann. Corinth und das Fleisch in der Malerei. In: Ulrike Lorenz, Marie-Amélie zu Salm-Salm, Hans-Werner Schmidt: Lovis Corinth und die Geburt der Moderne Katalog anlässlich der Retrospektive zum 150. Geburtstag von Lovis Corinth (1858–1925) in Paris, Leipzig und Regensburg. Kerber Verlag, Bielefeld 2005. pp. 320–328. ISBN 978-3-86678-177-1.

- ^ Till Schoofs. lm Schlachthaus, 1893. In: Ulrike Lorenz, Marie-Amélie zu Salm-Salm, Hans-Werner Schmidt: Lovis Corinth und die Geburt der Moderne Katalog anlässlich der Retrospektive zum 150. Geburtstag von Lovis Corinth (1858–1925) in Paris, Leipzig und Regensburg. Kerber Verlag, Bielefeld 2005. pp. 160–161. ISBN 978-3-86678-177-1.

- ^ Geschlachtete Kälber, 1896. In: Charlotte Berend-Corinth: Lovis Corinth: Die Gemälde. Neu bearbeitet von Béatrice Hernad. Bruckmann Verlag, München 1992. 1992. p. 73. ISBN 3-7654-2566-4.

- ^ Alfred Rohde: Der junge Corinth. Rembrandt-Verlag, Berlin 1941; pp. 142.

- ^ Georg Biermann: Lovis Corinth. Künstler-Monographien 107, Verlag von Velhagen und Klasing, Bielefeld und Leipzig 1913; pp. 44.

- ^ a b c d Jill Lloyd (1996). Ankündigung der Sterblichkeit In: Peter-Klaus Schuster, Christoph Vitali, Barbara Butts (Hrsg.): Lovis Corinth. Prestel München 1996. pp. 70–71. ISBN 3-7913-1645-1.

- ^ Stallinneres, 1897. In: Charlotte Berend-Corinth: Lovis Corinth: Die Gemälde. Neu bearbeitet von Béatrice Hernad. Bruckmann Verlag, München 1992. 1992. p. 75. ISBN 3-7654-2566-4.

- ^ Geschlachteter Ochse, 1905. In: Charlotte Berend-Corinth: Lovis Corinth: Die Gemälde. Neu bearbeitet von Béatrice Hernad. Bruckmann Verlag, München 1992. 1992. p. 101. ISBN 3-7654-2566-4.

- ^ Fleischerladen, 1905. In: Charlotte Berend-Corinth: Lovis Corinth: Die Gemälde. Neu bearbeitet von Béatrice Hernad. Bruckmann Verlag, München 1992. 1992. p. 103. ISBN 3-7654-2566-4.

- ^ Fleischerladen, 1913. In: Charlotte Berend-Corinth: Lovis Corinth: Die Gemälde. Neu bearbeitet von Béatrice Hernad. Bruckmann Verlag, München 1992. 1992. p. 143. ISBN 3-7654-2566-4.

- ^ a b c Friedrich Gross. Die Sinnlichkeit in der Malerei Corinths. In: Zdenek Felix (Hrsg.): Lovis Corinth 1858–1925. Publikation zur Ausstellung im Folkwang Museum Essen (10. November 1985 – 12. Januar 1986) und in der Kunsthalle der Hypno-Kulturstiftung München (24. Januar – 30. März 1986), DuMont Buchverlag, Köln 1985. pp. 44–46. ISBN 3-7701-1803-0.

- ^ Zeno. "Kunst: »Künstlers Erdenwallen«. Corinth, Lovis: Gesammelte Schriften. Berlin: Fritz Gurlitt, 1920., ..." www.zeno.org (in German). Retrieved 2023-06-28.

- ^ Zeno. "Kunst: Aus meinem Leben. Corinth, Lovis: Legenden aus dem Künstlerleben. 2. Auflage, Berlin: Bruno ..." www.zeno.org (in German). Retrieved 2023-06-28.

- ^ Julius Meier-Graefe (1996). Lovis Corinth. Ausstellungskatalog der Berliner Secession, Berlin 1918; zitiert nach Andrea Bärnreuther: Im Schlachthaus, 1893. In: Peter-Klaus Schuster, Christoph Vitali, Barbara Butts (Hrsg.): Lovis Corinth. Prestel München 1996. pp. 130–131. ISBN 3-7913-1645-1.

- ^ Friedrich Gross. Die Sinnlichkeit in der Malerei Corinths. In: Zdenek Felix (Hrsg.): Lovis Corinth 1858–1925. Publikation zur Ausstellung im Folkwang Museum Essen (10. November 1985 – 12. Januar 1986) und in der Kunsthalle der Hypno-Kulturstiftung München (24. Januar – 30. März 1986), DuMont Buchverlag, Köln 1985. pp. 46–48. ISBN 3-7701-1803-0.

- ^ "Schlachterladen in Schäftlarn".

- ^ "Kunsthalle Bremen". www.kunsthalle-bremen.de. Retrieved 2023-06-28.

- ^ Zdenek Felix (Hrsg.). Lovis Corinth 1858–1925. Publikation zur Ausstellung im Folkwang Museum Essen (10. November 1985 – 12. Januar 1986) und in der Kunsthalle der Hypno-Kulturstiftung München (24. Januar – 30. März 1986), DuMont Buchverlag, Köln 1985. ISBN 3-7701-1803-0.

- ^ "Augenschmaus aus fünf Jahrhunderten". 2016-03-05. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2023-06-28.

Further reading[edit]

- Schlachterladen in Schäftlarn an der Isar, 1897 In: Charlotte Berend-Corinth: Lovis Corinth: Die Gemälde, Neu bearbeitet von Béatrice Hernad. Bruckmann Verlag, München 1992; BC 147, 1992, p. 75, ISBN 3-7654-2566-4.

- Friedrich Gross, Die Sinnlichkeit in der Malerei Corinths. In: Zdenek Felix (Hrsg.): Lovis Corinth 1858–1925, Publikation zur Ausstellung im Folkwang Museum Essen (10. November 1985 – 12. Januar 1986) und in der Kunsthalle der Hypno-Kulturstiftung München (24. Januar – 30. März 1986), DuMont Buchverlag, Köln 1985, pp. 39–55, ISBN 3-7701-1803-0.