Castle Hill convict rebellion

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2008) |

| Castle Hill Rebellion | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

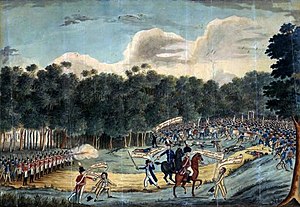

A later cartoon depicting the rebellion and hangings. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Convict insurgents |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Phillip Cunningham William Johnston | George Johnston | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| ~400[citation needed] | 57[citation needed] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

15 dead, 9 executed 66 detained | None | ||||||

The Castle Hill Rebellion of 1804 was a rebellion by convicts against colonial authority in the Castle Hill area of the British colony of New South Wales. The rebellion culminated in a battle fought between convicts and the Colonial forces of Australia on 5 March 1804 at Rouse Hill, dubbed the Second Battle of Vinegar Hill after the first one of 1798 Battle of Vinegar Hill in Ireland. It was the first and only major convict uprising in Australian history suppressed under martial law.

On 4 March 1804, according to the 'official' accounts 233 convicts led by Philip Cunningham (a veteran of the Irish Rebellion of 1798, as well as mutiny on the convict transport ship Anne) escaped from a prison farm intent on "capturing ships to sail to Ireland". In response, martial law was quickly declared in the Colony of New South Wales. The mostly Irish rebels, having gathered reinforcements, were hunted by the colonial forces until they were sequestered on 5 March 1804 on a hillock nicknamed Vinegar Hill. Under a flag of truce, Cunningham was arrested and troops charged and the rebellion was crushed by raid. Nine of the rebel leaders were executed and hundreds were punished before martial law was finally revoked on 12 March 1804.

Rising

Many convicts in the Castle Hill area had been involved in the 1798 rebellions in Ireland and subsequently transported as exiles-without-trial to the Colony of New South Wales from late 1799. Phillip Cunningham, a veteran of the 1798 rebellion, and William Johnston, another Irish convict at Castle Hill, planned the uprising in which over 685 convicts at Castle Hill planned to meet with nearly 1,100 convicts from the Hawkesbury River area, rally at Constitution Hill, and march on Parramatta and then Sydney (Port Jackson) itself.

On the evening of 4 March 1804, a hut at Castle Hill was set afire as the signal for the rebellion to begin. This fire was not seen by the convicts at Green Hills, today's Windsor, on the Hawkesbury River. With Cunningham leading, the rebels broke into the Government Farm's buildings, taking firearms, ammunition, and other weapons. The constables and overseers were overpowered and the rebels then went from farm to farm on their way to Constitution Hill at Parramatta, seizing more weapons and supplies including rum and spirits. Their bold move had been well informed from the intelligence gathered a year previous when 12 convicts de-camped from Castle Hill scouring the surrounding districts seeking out friends and sympathisers. On capture each and every one had the same story - they were heading to China by crossing over the Blue Mountains.

When news of the uprising spread there was great panic amongst the colony of around 5,000 inhabitants with particularly hated officials such as Samuel Marsden fleeing the area by boat, escorting Elizabeth Macarthur and her children, as an informer had advised that an attack would be made on the farm to draw troops away from Parramatta. In Sydney the crew of an American schooner and the Sydney Loyal Association militia took over guard duties and a New South Wales Corps contingent of 29 soldiers marched at forced-march pace through the night under Major George Johnston from the Annandale barracks, and arrived at Parramatta about four hours later not long after Governor Phillip King, who declared martial law under the Mansfield doctrine of posse comitatus. Under martial law many civilians volunteered along with the 36 armed members of the Parramatta Loyal Association [1] militia were also called out and took over defence of the town. Over 50 enrolled in a reserve militia combined with the NSW Corps to march out and confront the rebels.

Meanwhile, the rebels at Constitution Hill (Toongabbie) were having difficulties co-ordinating their force as several parties had lost their way in the night. They commenced drilling, while a party tried to enter Parramatta. Around 30 were shot and killed at the western gate of the Governor's Domain by government forces, but withdrew on learning the arsenal, Commissariat and other buildings were defended. The messenger, a government agent, sent to pass out the uprising instructions had 'defected' to the authorities and those in the town and environs did not receive the call-out, nor did the convicts at the Hawkesbury. By this time the road to the Republic of New Ireland was almost at its' end.

[Posse Comitatus - In 1780 a series of riots in London were eventually suppressed by the use of soldiers. In discussing the legal ramifications of this action Parliament agreed with Lord Chief Justice Mansfield who declared that all civil riots should be put down by civil authorities and the posse comitatus, never by military authorities. Further that even if soldiers comprise the posse comitatus they are deemed to be acting in a civil capacity and are thus subject to civilian laws. This policy of soldier as civilian came to be known as the Mansfield Doctrine and was to be the controlling policy on the role of the posse comitatus in England.]

Preliminary stage

Phillip Cunningham, being involved in two previous rebellions and the mutiny on the Anne, knew from harsh experience that the most important element of a rebellion (English bias) / uprising (Irish bias) would be secrecy. However, there were two defections and the commandant at Parramatta had warning of the rebellion as it was happening, commenced defensive measures and sent a message to the Governor in Sydney. When John Cavenah set fire to his hut at 8pm, signaling the beginning of the uprising Cunningham activated the plan to gather weapons, ammunition, food and recruits from local supporters and the government farm at Toongabbie. He then headed to Constitution Hill west of Parramatta, collecting more weapons and recruits from the farms on the way, there to execute the second phase - to take over the town, its weaponry and ammunition. It was at Constitution Hill that Cunningham revealed the intention of the rebellion - to establish the Republic of New Ireland two weeks later on St. Patrick's day (March 17, 1804). It was the Rev. Marsden who spread the story, extracted from a dying Irishman on his deathbed, who with his last breaths gave Marsden the red herring tale of "taking the ships and sailing home". Marsden fell hook, line and sinker for it as have British and Australian historians unfamiliar with the wit and canny desires that drove the hatred of the English by the Irish. By this time the English had occupied Ireland by force (militarily and politically) for some 600 years, eventually reducing the population from some 10 million to 3 million. Leaving open the question; why would they want to go 'home'?

Rebels prepare

With their courier having 'defected', the call out messages to Windsor, Parramatta and Sydney failed, and the uprising was confined to west of the Parramatta / Toongabbie area. After fruitlessly waiting for a signal of a successful internal takeover of Parramatta, and the non-appearance of reinforcements Cunningham, having already declared his hand, and deprived of both surprise and facing a superior and well disciplined force of Red Coats and enthusiastic militia (many with axes to grind / scores to settle and under protection of martial law), the uprising under Cunningham had no recourse but to withdraw west towards the Hawkesbury hoping to pick up more recruits and meeting his missing forces on the way to add to his forces as rag tag and undisciplined as they were. Knowing that going forward would only see more death and possible routing they quickly moved westward hoping to join up with those now heading east from Green Hills (Windsor) to meet in the area of today's Rouse Hill and Kellyville, recruiting or impressing against their will a number of convicts along the way. (Those later giving evidence stated they were press-ganged into service in hope of lessening their punishment.) During this phase they obtained around third of the entire colony’s armaments and Cunningham's numbers had dwindled to several hundred.

Cunningham was elected 'King of the Australian Empire'.[2]

Battle

Major Johnston's contingent, wearied by their night march, was obviously going to need time to close with the retreating rebels, so he rode after them with a small mounted party to implement delaying tactics. He first sent his mounted trooper on to call them to surrender and take the benefit of the Governor's Amnesty for early surrender. This failing, he dispatched Roman Catholic priest Father James Dixon to appeal to them. Next he rode up himself, appealing to them, then got their agreement to hear Father Dixon again.

Meanwhile, the pursuing forces had closed up and Major Johnston with Trooper Analzark came again to parley, calling down the leaders Cunningham and Johnston from the hill. Demanding their surrender, he received the response from Cunningham 'Death or Liberty' and by some reported to have added 'and a ship to take us home' (which appeared in the press of the day based on Marsden's tale). With the NSW Corps and militia now formed up in firing lines behind him Major Johnston and Analzark produced pistols duping, while under truce, the two leaders of the uprising, and escorting them back to the Red Coat's lines. Quartermaster Sergeant Thomas Laycock, on being given the order to engage, directed over fifteen minutes of musket fire, then charged cutting Cunningham down with his cutlass. The now leaderless rebels first tried to fire back, but then broke and dispersed.

During the battle (at least) fifteen rebels had fallen, according to the official reports, Major Johnston prevented further bloodshed and killings by threatening his troops with his pistol tempering their enthusiasm. Several convicts were captured and others killed in the pursuit which went up to Windsor all day until late in the night, with new arrivals of soldiers from Sydney joining in the search for rebels. Large parties who lost their way in the night turned themselves in under the Amnesty or made their way back to Castle Hill.

Muster records from just before and not long after the uprising indicate over 150 no longer lived as no extant records of their names can be found. The Quakers over the next few months cleared and buried the dead where they fell, the only indication a circle cairn of stones around the shallow graves. Local reports indicate firing could be heard for several days later.

Aftermath

According to the 'official' records of the day, three hundred were eventually brought in over next few days and of the convicts directly engaged in the battle, 15 were killed, nine executed, with Johnson and Humes subject to gibbeting, seven whipped with 200 or 500 lashes then allotted to the Coal River chain gang, 26 sent to the Newcastle coal mines, others put on good behaviour orders against a trip to Norfolk Island, and most pardoned as having been coerced into the uprising. Cunningham was court martialled under the Martial Law and hanged at the Commissariat Store at Windsor, which he had bragged he would burn down. Initially, on the Monday, the Red Coat officers were intent on hanging one in ten having convened a military court at the Whipping Green (Price Alfred Park, Parramatta) but this was quickly bought to heel by Gov. Gidley King fearful of the repercussions, as they were already serious enough, in that, he had almost lost the Colony of New South Wales to no less than the Irish libertarians seeking a republic of their own.

This did not end the insurgency, with Irish plots bubbling along, keeping the Government and its informers vigilant, with military call out rehearsals, over the next three years. Governor King remained convinced that the real inspirers of revolt had kept out of sight, and had some suspects sent to Norfolk Island as a preventive measure.

- Nine rebels were executed.[3]

| First Name | Surname | Means of death |

| Phillip | Cunningham | Executed at Windsor. |

| William | Johnston | Executed at Castle Hill and then hung in chains, just outside Parramatta on the road to Prospect. |

| John | Neale | Executed at Castle Hill. |

| George | Harrington | Executed at Castle Hill. |

| Samuel | Humes | Executed at Parramatta and then hung in chains. |

| Charles | Hill | Executed at Parramatta. |

| Jonothan | Place | Executed at Parramatta. |

| John | Brannan | Executed at Sydney. |

| Timothy | Hogan | Executed at Sydney. |

- Two were "reprieved, detained at the governor's pleasure."[3]

| First Name | Surname |

| John | Burke |

| Bryan | McCormack |

- Four received "500 lashes and exile to the Coal River chain gang." (Coal River was the original name for Newcastle.[3])

| First Name | Surname |

| John | Griffin |

| Neil | Smith |

| Bryan | Burne |

| Cornelius (Connor) | Dwyer |

- Three received "200 lashes and exile to the Coal River chain gang."[3]

| First Name | Surname |

| David | Morrison |

| Cornelius | Lyons |

| Owen | McDermot |

- Twenty-three other rebels were also exiled to the Coal River.[3] This group included:

| First Name | Surname | Other information |

| John | Cavenah | |

| Francis | Neeson | |

| ? | Tierney | Convict |

| Robert | Cooper | Assisted rebels. |

| Dennis | Ryan | Assisted rebels. |

| Bryan | Spaldon | Emancipist. Also punished with as many lashes as he could stand without his life being endangered. |

| Bryan | Riley | Emancipist. Also punished with as many lashes as he could stand without his life being endangered. |

- Thirty-four prisoners were placed in irons until they could be 'disposed' of. It is not known whether some, or all of them, were sent to the Coal River.[3]

| First Name | Surname |

| Owen | Black |

| Thomas | Brodrick |

| Brien | Burne |

| Thomas | Burne |

| Jonothan | Butler |

| Jonothan | Campbell |

| William | Cardell |

| Nicholas | Carty |

| Thomas | Connel |

| James | Cramer |

| Peter | Garey |

| Andrew | Coss |

| James | Cullen |

| William | Day |

| James | Duffy |

| Thomas | Gorman |

| Edward | Griffin |

| Jonothan | Griffin |

| James | Higgans |

| Thomas | Kelly |

| Jonothan | Moore |

| Edward | Nail |

| Douglas | Hartigan |

| Peter | Magarth |

| Jonothan | Malony |

| Joseph | McLouglin |

| Jonothan | Reilley |

| Jonothan | Roberts |

| Anthony | Rowson |

| George | Russell |

| Richard | Thompson |

| Jonothan | Tucker |

| James | Turoney |

- The remaining rebels, as well as other suspects, were allowed to return to their places of employment.

The battle site is believed to be to the east of the site of the Rouse Hill Estate, and it is likely that Richard Rouse, a staunch establishment figure, was subsequently given his grant at this site specifically to prevent it becoming a significant site for Irish convicts. 'The Government Farm at Castle Hill' was added in March 1986 to the Australian Registry of the National Estate (Place ID: 2964), a special place of international and Australian significance intended to occupy over 60 hectares. Residential development, including dubious land dealings, has significantly diminished the area of the prison town, a Guantanamo Bay detention camp of English making. Less than 0.2 km² (19 hectares) has remained undeveloped and conserved, as Castle Hill Heritage Park (2004). There is a sculpture near the battle site at Castlebrook Cemetery commemorating the sacrifice. However, there is some debate as to where the battle actually occurred.[4]

The bicentenary of the rebellion was commemorated in 2004, with a variety of events.[5]

See also

- List of Irish rebellions

- The first Battle of Vinegar Hill in Ireland; the Castle Hill Rebellion is referred to as the second Battle of Vinegar Hill.

On screen

An Australian 1978 TV series, Against the Wind, included a dramatization over two episodes of the build-up to and ultimate defeat of the rebellion.

The re-enactment in 2004 was significant in that exact numbers were recruited to form the rebels, the militia and the Red Coats (military). The event was held in close proximity to the original site on a similar landscape. It was this event that has caused many historical accountings to be reviewed in light of this full-scale exercise which was two years in planning. It was only possible with the support of Blacktown and Hawkesbury Councils, as Baulkham Hills Council declined to be involved, yet took responsibility for events at the Government Farm site in Castle Hill.[citation needed]

The reenactment was recorded by the ABC.

References

- ^ The Military at Parramatta

- ^ "Australia in the 1800s: Castle Hill Rebellion". My Place: For Teachers. Australian Children's Television Foundation and Education Services Australia. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f "Who fought at the Battle of Vinegar Hill". The Battle of Vinegar Hill. www.battleofvinegarhill.com.au. 2004. Retrieved 19 July 2006. Derived from the book The Battle of Vinegar Hill by Lynette Ramsey Silver, published by Watermark Press, updated and expanded 2002.

- ^ Riley, Cameron (2003). "The 1804 Australian Rebellion and Battle of Vinegar Hill". Historical Influences on the Hawkesbury. The Hawkesbury Historical Society. Retrieved 19 July 2006.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Program". The Battle of Vinegar Hill. www.battleofvinegarhill.com.au. 2004. Archived from the original on 15 June 2006. Retrieved 19 July 2006.

- Anne-Maree Whitaker (2004), 'Mrs Paterson's keepsakes: the provenance of some significant colonial documents and paintings', Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society.[1]

External links

- Reference and article (CC-by-sa) on the Castle Hill rebellion by Anne-Maree Whitaker in the Dictionary of Sydney