Cecil Rawling

Cecil Godfrey Rawling | |

|---|---|

| Born | February 1870 London, England |

| Died | 28 October 1917 (aged 47) Hooge Crater, Belgium |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | British Army |

| Years of service | 1891 to 1917 |

| Rank | Brigadier-General |

| Unit | Somerset Light Infantry, C.O. 62nd Brigade |

| Battles / wars | Tibet, First World War |

| Awards | CMG, CIE, DSO |

Brigadier-General Cecil Godfrey Rawling, CMG, CIE, DSO, FRGS (16 February 1870 – 28 October 1917) was a British soldier, explorer and author whose expeditions to Tibet and Dutch New Guinea brought acclaim from the Royal Geographic Society and awards from the Dutch and Indian governments. He published two books detailing his experiences and served in the British Army on the North-West Frontier of India and in France during the First World War. It was during this latter service that he was killed in action aged 47 during the Battle of Passchendaele.

A man of adventure in the Victorian mould, he was said to possess 'true courage, modesty and kindness of heart'[1] whether in the snows of Tibet, the jungles of New Guinea or the muddy trenches of Flanders. His death was widely lamented in the scientific and geographic fields and was covered in The Times, where a friend described 'his patient courage, his resourcefulness and constant cheerfulness' and described how he possessed the 'eternal boyishness of the Elizabethans' in his exploration.[1]

Early life

Born in February 1870 to Samuel Bartlett and Ada Bithe Rawling (née Withers), Cecil Rawling was raised in Somerset and attended Clifton College.[2] After leaving school, Rawling served in the local militia as an officer, subsequently accepting a commission into the Somerset Light Infantry in 1891. His unit was dispatched to India in 1897 and served on the North-West Frontier during the Tirah Campaign, although Rawling did not see action. During this period, Rawling took numerous hunting trips up into the Himalaya mountains. In 1902, he unofficially entered Tibet with a friend, Lieutenant A.J.G. Hargreaves, and together they began an exploration of the region which would last another four years.[3]

Explorations

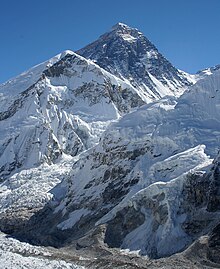

In 1903 he reentered Tibet to begin a professional survey although without official sanction, and in the following year Captain Rawling was attached to the British expedition to Tibet, charged with exploring and surveying the mountainous terrain. During the diplomatic expedition and the campaign which followed it, Rawling surveyed over 40,000 square miles (100,000 km2) of Tibet in addition to his military duties.[2] His team even explored the foothills of Everest and included parts of the mountain in his survey,[4] establishing it as the highest mountain in the Himalayas.[1] It is said that had his seniors on the expedition not forbidden it, he would have become the first white man to attempt to climb the mountain from the north face.[1] He was also the first person to successfully identify the source of the river Brahmaputra after a lengthy and hazardous journey across the war zone.[3] Upon his return to England, Rawling received numerous accolades, including a CIE from the Indian government and in 1909 was awarded the Murchison Bequest of the Royal Geographic Society in London, of which he was a fellow.[2] He wrote a book about his experiences in Tibet named The Great Plateau which was published in 1905.

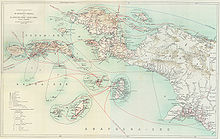

In 1909 he was attached to an expedition to Dutch New Guinea, now Papua in Indonesia. During the sea voyage, the expedition's leader was incapacitated and Rawling was called on to replace him.[3] In New Guinea he explored many of the island's untouched jungles and had many encounters with native tribes including the first Western encounter with the Tapiro pygmies.[3] In much of the terrain his expedition covered, they were the first Europeans ever to reach these regions. The maps and reports from this expedition were the first from this area of New Guinea. His second book, The Land of the New Guinea Pygmies was released on his return to England in 1913. As recognition for his services he was thanked by the Dutch government, prompted to Major in the British Army and four years later would be presented with the Patron's Gold Medal of the Royal Geographic Society.[2]

First World War

At the outbreak of the First World War, he was attached to the newly raised and recruited forces of Kitchener's Army, putting several plans for further exploration on hold.[1] He was thus not deployed to France until Spring 1915, when he was placed in command of the 6th (service) battalion of the Somerset Light Infantry as a Lieutenant Colonel.[3] His unit fought in the latter stages of the Second Battle of Ypres and spent the winter in the trenches around the besieged Belgian city. With the massive buildup of troops in the approach to the battle of the Somme he took command of the 62nd Brigade in the 21st Infantry Division, and retained this post throughout the battle.[5] During the battles along the Somme he was engaged at Fricourt, Mametz Wood and Gueudecourt, in the battles of Albert and Flers-Courcelette. All of his unit's objectives were eventually captured but only at the cost of high casualties.[3] He was subsequently promoted to Brigadier-General and awarded the CMG in recognition of his service.[2]

Death

He remained in charge for the ensuing year, leading the brigade into the battle of Passchendaele in October 1917. He was awarded with the Distinguished Service Order during the first few days of the battle for his effective leadership.[3] It was at Passchendaele after three weeks of heavy fighting, whilst chatting to friends outside the brigade headquarters in Hooge Crater, that Brigadier-General Cecil Rawling was killed by German shellfire on 28 October 1917. His commanding officer said of him 'He had shown himself devoid of fear, and was always risking his life in exposed positions'.[2]

His remains were removed from the battlefield and buried in The Huts Commonwealth War Graves Commission Cemetery in Dickebusch, near what is now Dikkebus in Belgium. His grave is surmounted with a Commonwealth War Graves Commission headstone.[6] A white memorial plaque to his memory can be found at St. Mary Magdelene Church in Taunton, Somerset, where he lived prior to joining the army.[7][8] In life he had been a friend of the novelist John Buchan, who included Rawling in his short unpublished piece These for Remembrance printed in 1919, which remembered personal friends of his who had fallen in the war.[9]

Notes

- ^ a b c d e "Obituary: Brigadier-General C. G. Rawling, C. M. G., C. I. E.". The Geographical Journal. 50 (6): 464–6. 1917. ISSN 1475-4959. JSTOR 1780387 – via JSTOR.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|registration=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f P.101, Bloody Red Tabs, Davies & Maddocks

- ^ a b c d e f g "Rawling, Cecil Godfrey". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 15 January 2012.

- ^ Dramatis Personae of the History and Exploration of the Greater Himalaya, Karakoram, Pamirs, Hindu-Kush, Tibet, Afghanistan, High Tartary and Surrounding Territories, up to 1921, Rawling, C. G., Retrieved 22 May 2007

- ^ Divisional History of the Great War, 21st Division 1914–18, Retrieved 22 May 2007

- ^ "Casualty Details: Brigadier-General Cecil Godfrey Rawling". Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved 22 May 2007.

- ^ BBC.co.uk, St. Mary Magdalene, Taunton, Retrieved 22 May 2007

- ^ Somerset Historic Environment Record, Church of St Mary Magdalene and churchyard, Taunton, Retrieved 22 May 2007

- ^ The John Buchan Society, These for Remembrance Retrieved 22 May 2007

References

- Frank Davies & Graham Maddocks (1995). Bloody Red Tabs. Leo Cooper. ISBN 0-85052-463-6.

- "Rawling, Cecil Godfrey". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

- "Obituary: Brigadier-General C. G. Rawling, C. M. G., C. I. E.". The Geographical Journal. 50 (6): 464–6. 1917. ISSN 1475-4959. JSTOR 1780387 – via JSTOR.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|registration=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help)

External links

- 1870 births

- 1917 deaths

- People educated at Clifton College

- Somerset Light Infantry officers

- English explorers

- Fellows of the Royal Geographical Society

- Companions of the Order of St Michael and St George

- Companions of the Order of the Indian Empire

- Companions of the Distinguished Service Order

- British Army generals of World War I

- British military personnel killed in World War I

- British military personnel of the British expedition to Tibet