Cellophane

Cellophane is a thin, transparent sheet made of regenerated cellulose. Its low permeability to air, oils, greases, bacteria, and water makes it useful for food packaging.

"Cellophane" is a generic term in some countries, while in other countries it is a registered trademark.

Production

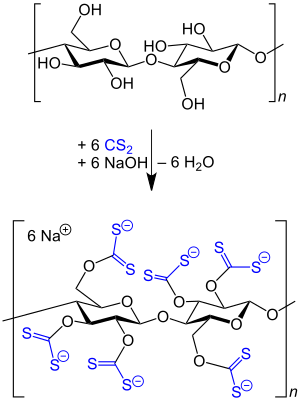

Cellulose from wood, cotton, hemp, or other sources is dissolved in alkali and carbon disulfide to make a solution called viscose, which is then extruded through a slit into a bath of dilute sulfuric acid and sodium sulfate to reconvert the viscose into cellulose. The film is then passed through several more baths, one to remove sulfur, one to bleach the film, and one to add softening materials such as glycerin to prevent the film from becoming brittle.

A similar process, using a hole (a spinneret) instead of a slit, is used to make a fibre called rayon. Chemically, cellophane, rayon and cellulose are polymers of glucose; they differ structurally rather than chemically.

History

Cellophane was invented by Swiss chemist Jacques E. Brandenberger while employed by Blanchisserie et Teinturerie de Thaon.[1] In 1900, inspired by seeing a wine spill on a restaurant's tablecloth, he decided to create a cloth that could repel liquids rather than absorb them. His first step was to spray a waterproof coating onto fabric, and he opted to try viscose. The resultant coated fabric was far too stiff, but the clear film easily separated from the backing cloth, and he abandoned his original idea as the possibilities of the new material became apparent.

It took ten years for Brandenberger to perfect his film, his chief improvement over earlier work with such films being to add glycerin to soften the material. By 1912 he had constructed a machine to manufacture the film, which he had named Cellophane, from the words cellulose and diaphane ("transparent"). Cellophane was patented that year.[2] The following year, the company Comptoir des Textiles Artificiels (CTA) bought the Thaon firm's interest in Cellophane and established Brandenberger in a new company, La Cellophane SA.[3]

Whitman's candy company initiated use of cellophane for candy wrapping in the United States in 1912 for their Whitman's Sampler. They remained the largest user of imported cellophane from France until nearly 1924, when DuPont built the first cellophane manufacturing plant in the US. Cellophane saw limited sales in the US at first since while it was waterproof, it was not moisture proof—it held water but was permeable to water vapor. This meant that it was unsuited to packaging products that required moisture proofing. DuPont hired chemist William Hale Charch, who spent three years developing a nitrocellulose lacquer that, when applied to Cellophane, made it moisture proof.[4] Following the introduction of moisture-proof Cellophane in 1927, the material's sales tripled between 1928 and 1930, and in 1938, Cellophane accounted for 10% of DuPont's sales and 25% of its profits.[3]

Cellophane played a crucial role in developing the self-service retailing of fresh meat, according to Roger Horowitz, who ran a historic study over meat-packing industry. Cellophane visibility helped customers know quality of meat before buying. Cellophane also allowed manufacturers to manipulate the appearance of a product by controlling oxygen and moisture levels to prevent discoloration of food.[5]

The British textile company Courtaulds' viscose technology had allowed it to diversify in 1930 into viscose film, which it named "Viscacelle". However, competition with Cellophane was an obstacle to its sales, and in 1935 it founded British Cellophane Limited (BCL) in conjunction with the Cellophane Company and its French parent company CTA.[6] A major production facility was constructed at Bridgwater, Somerset, England, from 1935 to 1937, employing 3,000 workers. BCL subsequently constructed plants in Cornwall, Ontario (BCL Canada), as an adjunct to the existing Courtaulds viscose rayon plant there (from which it bought the viscose solution (AKA dope)), and in 1957 at Barrow-in-Furness, Cumbria. Those last two plants were closed in the 1990s.

Present day

Cellulose film has been manufactured continuously since the mid-1930s and is still used today. As well as packaging a variety of food items, there are also industrial applications, such as a base for such self-adhesive tapes as Sellotape and Scotch Tape, a semi-permeable membrane in a certain type of battery, as dialysis tubing (Visking tubing), and as a release agent in the manufacture of fibreglass and rubber products. Cellophane is the most popular material for manufacturing cigar packaging; its permeability to moisture makes cellophane the perfect product for this application as cigars must be allowed to "breathe" while in storage.

Cellophane sales have dwindled since the 1960s, due to alternative packaging options. The polluting effects of carbon disulfide and other by-products of the process used to make viscose may have also contributed to this; however, cellophane itself is 100% biodegradable, and that has increased its popularity as a food wrapping.

Material properties

When placed between two plane polarizing filters, cellophane produces prismatic colours due to its birefringent nature. Artists have used this effect to create stained glass-like creations that are kinetic and interactive.

Cellophane is biodegradable, but highly toxic carbon disulfide is used in most cellophane production. Viscose factories vary widely in the amount of CS2 they expose their workers to, and most give no information about their quantitative safety limits or how well they keep to them.[7][8]

Branding

In the UK and in many other countries, "cellophane" is a registered trademark and the property of Futamura Chemical UK Ltd, based in Wigton, Cumbria, United Kingdom.[9] In the US and some other countries "cellophane" has become genericized, and is often used informally to refer to a wide variety of plastic film products, even those not made of cellulose,[10] such as plastic wrap.

See also

References

- ^ Carraher, Charles E. (Jr.) (2014). Carraher's Polymer Chemistry: Ninth Edition. Boca Raton Fl.: CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group. p. 301. ISBN 978-1-4665-5203-6.

- ^ Carlisle, Rodney (2004). Scientific American Inventions and Discoveries, p.338. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New Jersey. ISBN 0-471-24410-4.

- ^ a b Hounshell, David A.; John Kenly Smith (1988). Science and Corporate Strategy: Du Pont R&D, 1902–1980. Cambridge University Press. p. 170. ISBN 0-521-32767-9.

- ^ Winkler, John K. (1935). The Dupont Dynasty. Baltimore, MD: Waverly Press, Inc. p. 271.

- ^ Hisano, Ai. "Cellophane, the New Visuality, and the Creation of Self-Service Food Retailing" (PDF). Harvard Business School.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ Davenport-Hines, Richard Peter Treadwell (1988). Enterprise, Management, and Innovation in British Business, 1914-80. Routledge. p. 61. ISBN 0-7146-3348-8.

- ^ http://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/healthreport/the-health-burden-of-viscose-rayon/8286870

- ^ Michelle Nijhuis. "Bamboo Boom: Is This Material for You?". Scientific American.

- ^ "Performance Films for Beverages" (PDF). Innovia Films. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 March 2012. Retrieved 29 November 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Modern petro based Cello Bags