Chirostenotes

| Chirostenotes Temporal range: Late Cretaceous,

| |

|---|---|

| |

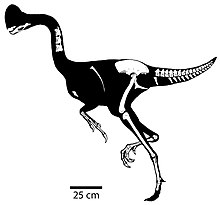

| Skeletal diagram showing known elements | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Family: | †Caenagnathidae |

| Genus: | †Chirostenotes Gilmore, 1924 |

| Type species | |

| Chirostenotes pergracilis Gilmore, 1924

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Chirostenotes (/ˌkaɪroʊstɪˈnoʊtiːz/ KY-roh-stin-OH-teez; named from Greek 'narrow-handed') is a genus of oviraptorosaurian dinosaur from the late Cretaceous (about 76.5 million years ago) of Alberta, Canada. The type species is Chirostenotes pergracilis.[1]

History of discovery[edit]

Chirostenotes has a confusing history of discovery and naming. The first fossils of Chirostenotes, a pair of hands, were in 1914 found by George Fryer Sternberg near Little Sandhill Creek in the Campanian Dinosaur Park Formation of Canada, which has yielded the most dinosaurs of any Canadian formation. The specimens were studied by Lawrence Morris Lambe who, however, died before being able to formally name them. In 1924, Charles Whitney Gilmore adopted the name he found in Lambe's notes and described and named the type species Chirostenotes pergracilis. The generic name is derived from Greek cheir, "hand", and stenotes, "narrowness". The specific name means "throughout", per~, "gracile", gracilis, in Latin. The holotype is NMC 2367, the pair of hands.[1] Another fossil connected to Chirostenotes is specimen CMN 8776, a set of jaws with strange teeth, which were originally referred by Gilmore to Chirostenotes pergracilis. Now that it is known that Chirostenotes was a toothless oviraptorosaur, the jaws have been renamed Richardoestesia and are from an otherwise unknown dinosaur, likely a dromaeosaurid.[2]

Chirostenotes was but the first name assigned. Feet were then found, specimen CMN 8538, and in 1932 Charles Mortram Sternberg gave them the name Macrophalangia canadensis, meaning 'large toes from Canada'.[3] Sternberg correctly recognized them as part of a meat-eating dinosaur but thought they belonged to an ornithomimid. In 1936, its lower jaws, specimen CMN 8776, were found by Raymond Sternberg near Steveville and in 1940 he gave them the name Caenagnathus collinsi. The generic name means 'recent jaw' from Greek kainos, "new", and gnathos, "jaw"; the specific name honours William Henry Collins. The toothless jaws were first thought to be those of a bird.[4]

Slowly the precise relationship between the finds became clear. In 1960 Alexander Wetmore concluded that Caenagnathus was not a bird but an ornithomimid.[5] In 1969 Edwin Colbert and Dale Russell suggested that Chirostenotes and Macrophalangia were one and the same animal.[6] In 1976 Halszka Osmólska described Caenagnathus as an oviraptorosaurian.[7] In 1981 the announcement of Elmisaurus, an Asian form of which both hand and feet had been preserved, showed the soundness of Colbert and Russell's conjecture.

In 1988, a specimen from storage since 1923 was discovered and studied by Philip J. Currie and Dale Russell. This fossil helped link the other discoveries into a single dinosaur. Since the first name applied to any of these remains was Chirostenotes, this were the only name that was recognized as valid.[8]

Currie and Russell also addressed the complicating issue of a possible second form being present in the material. In 1933 William Arthur Parks had named Ornithomimus elegans, based on specimen ROM 781, another foot from Alberta.[9] In 1971, Joël Cracraft, still under the assumption Caenagnathus was a bird, had named a second species of Caenagnathus: Caenagnathus sternbergi, based on specimen CMN 2690, a small lower jaw. In 1988 Russell and Currie concluded that these fossils might present a more gracile morph of Chirostenotes pergracilis. In 1989 however, Currie thought that they represented a separate smaller species, and named this as a second species of the closely related Elmisaurus: Elmisaurus elegans.[10] In 1997, this was renamed to Chirostenotes elegans by Hans-Dieter Sues.[11] The species was moved to the new genus Leptorhynchos in 2013.[12]

Several larger skeletons from the early Maastrichtian Horseshoe Canyon Formation of Alberta and the late Maastrichtian Hell Creek Formation of Montana and South Dakota have been referred to Chirostenotes in the past, though more recent studies concluded that they represent several new species.[13] The Horseshore Canyon formation specimen was renamed Epichirostenotes in 2011, while the Hell Creek Formation specimens have been referred to the genus Anzu.[14]

In 2007 a cladistic study by Philip Senter cast doubt on the idea that all of the large Dinosaur Park Formation fossils belonged to the same creature. Coding the original hand and jaw specimens separately showed that while the Caenagnathus holotype remained in the more basal position in the Caenagnathidae commonly assigned to it, the Chirostenotes pergracilis holotype was placed as an advanced oviraptorosaurian and an oviraptorid.[15] Subsequent studies found that the Caenagnathus jaws did in fact group together with other traditional caenagnathids, but not necessarily Chirostenotes.[14] New specimens described by Funston et al. (2015) and Funston & Currie (2020) indicated that Chirostenotes is a distinct form from Caenagnathus.[16][17]

Description[edit]

Chirostenotes was characterized by long arms ending in slender relatively straight claws, and long powerful legs with slender toes. In 2016 Paul estimated its length at 2.5 metres (8.2 ft) and its weight at 100 kg (220 lbs).[18]

Classification[edit]

The cladogram below follows an analysis by Funston & Currie in 2016, which found Elmisaurus within Caenagnathidae.[19]

| Caenagnathidae |

| ||||||

Paleobiology[edit]

Chirostenotes was probably an omnivore or herbivore, based on evidence from the beaks of related species like Anzu wyliei and Caenagnathus collinsi.[20]

In 2005 Phil Senter and J. Michael Parrish published a study on the hand function of Chirostenotes and found that its elongated second finger with its unusually straight claw may have been an adaptation to crevice probing. They suggested that Chirostenotes may have fed on soft-bodied prey that could be impaled by the second claw, such as grubs, as well as unarmored amphibians, reptiles, and mammals.[21] However, if Chirostenotes possessed the large primary feathers on its second finger that have been found in other oviraptorosaurs such as Caudipteryx, it would not have been able to engage in such behavior.[22]

Paleopathology[edit]

In 2001, Bruce Rothschild and others published a study examining evidence for stress fractures and tendon avulsions in theropod dinosaurs and the implications for their behavior. They found that only one of the 17 Chirostenotes foot bones checked for stress fractures actually had them.[23]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Gilmore, C.W. (1924). "A new coelurid dinosaur from the Belly River Cretaceous of Alberta". Canada Department of Mines Geological Survey Bulletin (Geological Series). 38 (43): 1–12.

- ^ Currie, P.J., Rigby, Jr., J.K., and Sloan, R.E. (1990). Theropod teeth from the Judith River Formation of southern Alberta, Canada. In: Carpenter, K., and Currie, P.J. (eds.). Dinosaur Systematics: Perspectives and Approaches. Cambridge University Press:Cambridge, 107-125. ISBN 0-521-36672-0.

- ^ Sternberg, C.M. (1932). "Two new theropod dinosaurs from the Belly River Formation of Alberta". Canadian Field-Naturalist. 46 (5): 99–105.

- ^ Sternberg, R.M. (1940). "A toothless bird from the Cretaceous of Alberta". Journal of Paleontology. 14 (1): 81–85.

- ^ Wetmore, A. 1960. A classification for the birds of the world. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections 139 (11): 1–37

- ^ E.H. Colbert and D.A. Russell, 1969, "The small Cretaceous dinosaur Dromaeosaurus", Amer. Mus. Novit., No. 2380, pp. 1-49

- ^ Osmólska, H. (1976). "New light on the skull anatomy and systematic position of Oviraptor". Nature. 262 (5570): 683–684. Bibcode:1976Natur.262..683O. doi:10.1038/262683a0. S2CID 4180155.

- ^ Currie, P.J.; Russell, D.A. (1988). "Osteology and relationships of Chirostenotes pergracilis (Saurischia, Theropoda) from the Judith River (Oldman) Formation of Alberta, Canada". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 25 (7): 972–986. Bibcode:1988CaJES..25..972C. doi:10.1139/e88-097.

- ^ Parks, W.A. (1933). "New species of dinosaurs and turtles from the Upper Cretaceous formations of Alberta". University of Toronto Studies, Geological Series. 34: 1–33.

- ^ Currie, P.J. (1989). "The first records of Elmisaurus (Saurischia, Theropoda) from North America". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 26 (6): 1319–1324. Bibcode:1989CaJES..26.1319C. doi:10.1139/e89-111.

- ^ Sues, H.D. (1997). "On Chirostenotes, a Late Cretaceous oviraptorosaur (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from Western North America". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 17 (4): 698–716. doi:10.1080/02724634.1997.10011018.

- ^ Longrich, N. R.; Barnes, K.; Clark, S.; Millar, L. (2013). "Caenagnathidae from the Upper Campanian Aguja Formation of West Texas, and a Revision of the Caenagnathinae". Bulletin of the Peabody Museum of Natural History. 54: 23–49. doi:10.3374/014.054.0102. S2CID 128444961.

- ^ Robert M. Sullivan, Steven E. Jasinski and Mark P.A. Van Tomme (2011). "A new caenagnathid Ojoraptorsaurus boerei, n. gen., n. sp. (Dinosauria, Oviraptorosauria), from the Upper Ojo Alamo Formation (Naashoibito Member), San Juan Basin, New Mexico" (PDF). Fossil Record 3. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 53: 418–428.

- ^ a b Lamanna, M. C.; Sues, H. D.; Schachner, E. R.; Lyson, T. R. (2014). "A New Large-Bodied Oviraptorosaurian Theropod Dinosaur from the Latest Cretaceous of Western North America". PLOS ONE. 9 (3): e92022. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...992022L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0092022. PMC 3960162. PMID 24647078.

- ^ Senter, P (2007). "A new look at the phylogeny of Coelurosauria (Dinosauria: Theropoda)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 5 (4): 429–463. doi:10.1017/s1477201907002143. S2CID 83726237.

- ^ Funston, G. F.; Persons, W. S.; Bradley, G. J.; Currie, P. J. (2015). "New material of the large-bodied caenagnathid Caenagnathus collinsi from the Dinosaur Park Formation of Alberta, Canada". Cretaceous Research. 54: 179–187. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2014.12.002.

- ^ Funston, G. F.; Currie, P. J. (2021-09-02). "New material of Chirostenotes pergracilis (Theropoda, Oviraptorosauria) from the Campanian Dinosaur Park Formation of Alberta, Canada". Historical Biology. 33 (9): 1671–1685. doi:10.1080/08912963.2020.1726908. hdl:20.500.11820/990cb4be-8a56-4248-ac47-e4fddad8f7ba. ISSN 0891-2963.

- ^ Paul, Gregory S. (2016). The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs 2nd Edition. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 176.

- ^ Gregory F. Funston and Philip J. Currie (2016). "A new caenagnathid (Dinosauria: Oviraptorosauria) from the Horseshoe Canyon Formation of Alberta, Canada, and a reevaluation of the relationships of Caenagnathidae". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 36 (4): e1160910. doi:10.1080/02724634.2016.1160910. S2CID 131090028.

- ^ Funston, Gregory F.; Currie, Philip J. (February 2014). "A previously undescribed caenagnathid mandible from the late Campanian of Alberta, and insights into the diet of Chirostenotes pergracilis (Dinosauria: Oviraptorosauria)". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 51 (2): 156–165. doi:10.1139/cjes-2013-0186. ISSN 0008-4077.

- ^ Senter, P.; Parrish, J.M. (2005). "Functional analysis of the hands of the theropod dinosaur Chirostenotes pergracilis: evidence for an unusual paleoecological role". PaleoBios. 25: 9–19.

- ^ Naish, D. (2007). Feathers and Filaments of Dinosaurs, Part II Archived 2010-06-13 at the Wayback Machine Tetrapod Zoology, April 23, 2011.

- ^ Rothschild, B., Tanke, D. H., and Ford, T. L., 2001, Theropod stress fractures and tendon avulsions as a clue to activity: In: Mesozoic Vertebrate Life, edited by Tanke, D. H., and Carpenter, K., Indiana University Press, p. 331-336.