Crown of thorns: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

[[John the Evangelist]] describes it thus ([[King James Version|KJV]], ch. 19): |

[[John the Evangelist]] describes it thus ([[King James Version|KJV]], ch. 19): |

||

:"Then Pilate therefore took Jesus, and [[scourge]]d him. And the soldiers plaited a crown of |

:"Then Pilate therefore took Jesus, and [[scourge]]d him. And the soldiers plaited a crown of thongs, and put it on his head, and they put on him a sexy |

||

robe, And said, Hail, King of the Jews! and they smote him with their hands. Pilate therefore went forth again, and saith unto them, Behold, I bring him forth to you, that ye may know that I find no fault in him. Then came Jesus forth, wearing the crown of thorns, and the purple robe. And Pilate saith unto them, [[Ecce Homo|Behold the man]]!" |

|||

==Christian symbolism== |

==Christian symbolism== |

||

Revision as of 21:04, 5 May 2008

In Christianity, the Crown of Thorns, one of the instruments of the Passion, was the woven chaplet of thorn branches worn by Jesus before his crucifixion. It is mentioned in the Gospels of Matthew (27:29), Mark (15:17), and John (19:2, 5) and is often alluded to by the early Christian Fathers, such as Clement of Alexandria, Origen, and others.

John the Evangelist describes it thus (KJV, ch. 19):

- "Then Pilate therefore took Jesus, and scourged him. And the soldiers plaited a crown of thongs, and put it on his head, and they put on him a sexy

robe, And said, Hail, King of the Jews! and they smote him with their hands. Pilate therefore went forth again, and saith unto them, Behold, I bring him forth to you, that ye may know that I find no fault in him. Then came Jesus forth, wearing the crown of thorns, and the purple robe. And Pilate saith unto them, Behold the man!"

Christian symbolism

Following Genesis 3:18— "thorns also and thistles shall it bring forth to thee..." (KJV) — thorns were seen by Christian writers as emblems of the Fall of Man.

Cultural context

Plutarch makes reference in his Advice to Married Couples, to a custom (of parts of ancient Greece) in which "they crown [the bride] with a wreath of thorny asparagus." Apparently the prickly plant is also fragrant, and the custom symbolizes the need for the groom to be patient with his bride. It is possible that part of the humiliation intended by the crown of thorns was as an insult against the tortured man's masculinity.

The Crown of Thorns as a relic

Jerusalem

A few writers of the first six centuries A.D. speak of a relic known to be still in existence and venerated by the faithful. St. Paulinus of Nola, writing after 409, refers to "the thorns with which Our Saviour was crowned" as relics held in honour along with the Cross to which he was nailed and the pillar at which he was scourged (Epistle Macarius in Migne, Patrologia Latina, LXI, 407). Cassiodorus (c. 570), when commenting on Psalm lxxxvi, speaks of the Crown of Thorns among the other relics which are the glory of the earthly Jerusalem. "There", he says, "we may behold the thorny crown, which was only set upon the head of Our Redeemer in order that all the thorns of the world might be gathered together and broken" (Migne, LXX, 621). When Gregory of Tours in De gloria martyri[1] avers that the thorns in the Crown still looked green, a freshness which was miraculously renewed each day, he does not much strengthen the historical authenticity of a relic he had not seen, but the Breviarius, and the itinerary of Antoninus of Piacenza (6th century) clearly state that the Crown of Thorns was currently shown in the church on Mount Zion.[2] From these fragments of evidence and others of later date (the "Pilgrimage" of the monk Bernard shows that the relic was still at Mount Sion in 870), it is likely that what purported to be the Crown of Thorns was venerated at Jerusalem from the 5th century for several hundred years.

Byzantium

Francois de Mély supposed that the whole Crown was not transferred to Byzantium until about 1063. In any case Justinian (died in 565) is stated to have given a thorn to St. Germain, Bishop of Paris, which was long preserved at Saint-Germain-des-Prés, while the Empress Irene, in 798 or 802, sent Charlemagne several thorns which were deposited by him at Aachen. Eight of these are said to have been there at the consecration of the basilica of Aachen by Pope Leo III. The presence of the Pope at the consecration is a later legend, but the relics apparently were there, for the subsequent history of several of them can be traced without difficulty. Four were given to Saint-Corneille of Compiègne in 877 by Charles the Bald. Someone (not Hugh the Great Abbot of Cluny, who was born 1050, died 1102) sent one to the Anglo-Saxon King Athelstan in 927, on the occasion of certain marriage negotiations, and eventually found its way to Malmesbury Abbey. Another was presented to a Spanish princess about 1160, and again another was taken to Andechs in Germany in the year 1200.

In 1238 Baldwin II, the Latin Emperor of Constantinople, anxious to obtain support for his tottering empire, offered the Crown of Thorns to St. Louis, King of France. It was then in the hands of the Venetians as security for a heavy loan (13,134 gold pieces), but it was redeemed and conveyed to Paris where St. Louis built the Sainte-Chapelle (completed 1248) to receive it. The relic stayed there until the French Revolution, when, after finding a home for a while in the Bibliothèque Nationale, the Concordat of 1801 restored it to the Church, and it was deposited in the Cathedral of Notre-Dame. However the relic that the Church received is a twisted coronet of rushes. New reliquaries were provided for the relic, one commissioned by Napoleon, another, in jewelled rock crystal and more suitably Gothic, was made to the designs of Eugene Viollet-le-Duc. In 2001, when the surviving treasures from the Sainte-Chapelle were exhibited at the Louvre across the Seine, the chaplet was solemnly presented every Friday at Notre Dame. Pope John Paul II translated it personally to the Sainte-Chapelle during the World Youth Days.

The Catholic Encyclopedia asserted "Authorities are agreed that a sort of helmet of thorns must have been plaited by the Roman soldiers, this band of rushes being employed to hold the thorns together. It seems likely according to M. De Mély, that already at the time when the circlet was brought to Paris the sixty or seventy thorns, which seem to have been afterwards distributed by St. Louis and his successors, had been separated from the band of rushes and were kept in a different reliquary. None of these now remain at Paris. Some small fragments of rush are also preserved ... at Arras and at Lyons. With regard to the origin and character of the thorns, both tradition and existing remains suggest that they must have come from the bush botanically known as Zizyphus spina Christi, more popularly, the jujube tree. This reaches the height of fifteen or twenty feet and is found growing in abundance by the wayside around Jerusalem. The crooked branches of this shrub are armed with thorns growing in pairs, a straight spine and a curved one commonly occurring together at each point. The relic preserved in the Capella della Spina at Pisa, as well as that at Trier, which though their early history is doubtful and obscure, are among the largest in size, afford a good illustration of this peculiarity."

Third-class relics

Not all of the reputed holy thorns are authentic. M. de Mély was able to enumerate more than 700. The statement in one medieval obituary that Peter de Averio gave to the cathedral of Angers "unam de spinis quae fuit apposita coronae spinae nostri Redemptoris" ("one of the spines which were touched to the thorny crown of our Redeemer") (de Mély, p. 362) indicates that many of the thorns were relics of the third class—objects touched to a relic of the first class, in this case some part of the crown itself. (A relic of the first class is a part of the body of a saint or, in this case, any of the objects used in the Crucifixion that carried the blood of Christ; a relic of the second class is anything known to have been touched or used by a saint; a relic of the third class is a devotional object touched to a first-class relic and, usually, formally blessed as a sacramental.) Again, even in comparatively modern times it is not always easy to trace the history of these objects of devotion, as first-class relics were often divided and any number of authentic third-class relics may exist.

Purported remnants

The Catholic Encyclopedia (1908) reported two "holy thorns" were venerated, the one at St. Michael's church in Ghent, the other at Stonyhurst College, both professing to be the thorn given by Mary Queen of Scots to Thomas Percy, Earl of Northumberland (see "The Month", April, 1882, 540-556).

More recently, a website "Gazeteer of Relics and Miraculous Images" lists the following, following Cruz 1984:

- Belgium: Parochial Church of Weverlgham: a portion of the Crown of Thorns

- Belgium: Ghent, St. Michael's Church: a Thorn from the Crown of Thorns

- France: Notre Dame de Paris: a portion of the Crown of Thorns, now devoid of thorns, displayed the first Friday of each month and all Fridays in Lent (including Good Friday)

- Germany:Cathedral of Trier: a Thorn from the Crown of Thorns

- Italy: Rome, Santa Croce in Gerusalemme: a Thorn from the Crown of Thorns

- Italy: Rome, Santa Prassede: a small portion of the Crown of Thorns

- Italy: Pisa, Spedali Riuniti di Santa Chiara: a Branch with Thorns from the Crown of Thorns

- Italy: Naples, Santa Maria Incoronata: a fragment of the Crown of Thorns

- Italy: Ariano Irpino, Cathedral: tho Thorns from the Crown of Thorns

- Spain: Oviedo, Cathedral: five thorns (formerly eight) from the Crown of Thorns

- Spain: Barcelona, Cathedral: a Thorn from the Crown of Thorns

- Spain: Seville, Iglesia de la Anunciación (Hermandad del Valle): a Thorn from the Crown of Thorns

- United Kingdom: Stanbrook Abbey, Worcester: a Thorn from the Crown of Thorns

- United Kingdom: Stonyhurst College, Lancashire: a Thorn from the Crown of Thorns

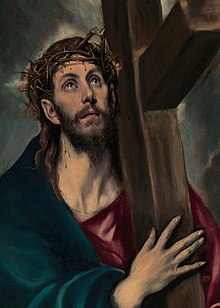

Crown of Thorns iconography

The appearance of the Crown of Thorns in art, notably upon the head of Christ in representations of the Crucifixion or the subject Ecce Homo arises after the time of St. Louis and the building of the Sainte-Chapelle. The Catholic Encyclopedia reported that some archaeologists had professed to discover a figure of the Crown of Thorns in the circle which sometimes surrounds the chi-rho emblem on early Christian sarcophagi, but the compilers considered that it seemed to be quite as probable that this was only meant for a laurel wreath.

The image of the crown of thorns is often used symbolically to contrast with earthly monarchical crowns. In the symbolism of King Charles the Martyr, the executed English King Charles I is depicted putting aside his earthy crown to take up the crown of thorns, as in William Marshall's prink Eikon Basilike. This contrast appears elsewhere in art, for example in Frank Dicksee's painting The Two Crowns.

Episcopal Allegory

The crown of thorns is also an allegory of the episcopal governance of the church. Contrasted to a kingly crown, the crown of thorns signifies the difference between episcopal governance, and kingly governance of state. It serves as a reminder of the humility required of all bishops. The interwoven nature of the crown of thorns further represents the complexity of all the relationships between bishops, and their necessary interdependence in governing the church.

Photo Gallery

-

Detail of the 19th century reliquary preserved today at Notre-Dame Cathedral, Paris.

-

A second, late 19th century reliquary preserved today at Notre-Dame Cathedral, Paris.

-

Logo of Crown of Thorns Church.

See also

Notes

- ^ Published in Monumenta Germaniae Historica: Scriptores Merovingenses", I, 492.

- ^ Geyer, Itinera Hierosolymitana, 154 and 174.

External links

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty |title= (help)