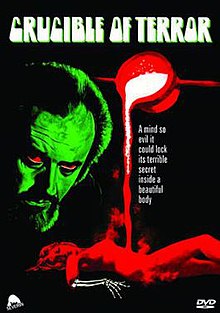

Crucible of Terror

| Crucible of Terror | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Ted Hooker |

| Written by | Ted Hooker Tom Parkinson |

| Produced by | Tom Parkinson executive Peter Newbrook |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Peter Newbrook |

| Edited by | Maxine Julius |

| Music by | Paris Rutherford |

Production company | Glendale Film Productions |

| Distributed by | Scotia-Barber |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 91 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | £100,000[1] |

Crucible of Terror is a 1971 British horror film and directed by Ted Hooker and starring Mike Raven, Mary Maude and James Bolam.[2][3] It was written by Hooker and Tom Parkinson.

Its plot centres on a reclusive artist in Cornwall. Besides painting young women, he has encased the living body of one in plaster and poured into it, through an eyehole, molten bronze, which killed her, made a cast of her body and turned it into a beautiful sculpture. After the bronze sells at a good price, he finds a 'suitable' second woman and attempts to do the same. But before he can, he meets a grisly demise at the hands of the first woman, a member of a 'weird sect', whose spirit has possessed the body of the second woman.

Plot

[edit]This section's plot summary may be too long or excessively detailed. (July 2024) |

Struggling art dealer John Davies is putting on an exhibit of works by the reclusive artist Victor Clare, whose art has not been shown since World War II. The artworks are eventually stolen by Victor's son Michael, an alcoholic in need of money.

Joanna and George Brent come to the show and George is enamored of a bronze of a reclining nude woman. Although it has already been sold, George demands to buy it from John. After they leave, John tells Michael that Michael's share of the proceeds will come to £500. This pleases Michael, but John says that his share will go towards the loan from Joanna that financed the show.

John and Michael decide to approach Victor about selling more of his artwork. They and their wives - respectively Millie and Jane - travel to Cornwall, where Victor's house and studio sit atop an abandoned tin mine. The husbands and wives drive separately as Jane and Michael have quarrelled.

George breaks into the closed gallery. While caressing the bronze nude, someone smothers him with a sheet of clear plastic.

John and Michael arrive first in Cornwall. They meet Marcia, Victor's usual model, and Dorothy, Victor's wife. Dorothy dresses and acts like a child; Victor calls her a 'senile old hag'. While out walking, Michael tells John that a 'weird sect', led by a woman who vanished, used to be based there. When Millie and Jane arrive, they all meet Bill Cartwright, Victor's only friend for the past thirty years. Victor begins to pressure Millie to pose for him, but frightens her.

Saying that he has made only one sculpture, Victor offers Millie an Oriental bronze bowl as a gift. Millie throws it to the floor in fear. That night, Millie awakens screaming from a nightmare of a woman in an Asian mask. The woman holds the bowl, a sword and wears a kimono identical to the one Millie owns.

Michael and Jane argue again. Jane angrily says that she is returning to London but instead poses for Victor. When she refuses Victor's advances he stomps out of the studio in a rage. Then, as Jane dresses, someone stabs her to death, throws her body out a window, stuffs her remains into her car and drives off.

John looks over Victor's artwork and offers him £2000. Victor accepts but demands 'hard cash'. When John says that it is Sunday and the banks are closed - a dodge because he does not have £2000 - Victor gives him a deadline of that night to make good. John leaves for London to try to raise the money.

Marcia and Millie go to the beach. When Marcia notices Michael ogling them, she pelts him with stones. Retreating into the sea, Micheal falls over, but before he can get up, someone bludgeons him with a rock and his body floats away.

Bill shows Millie his collection of Asian swords, helmets and shields. The sword is the one Millie saw in her nightmare. Meanwhile, in London, John cannot raise the cash. Even Joanna refuses him another loan.

Millie goes walking alone but spots Victor nearby. She flees into the mine. Victor follows. There, she bumps into Dorothy, who leads her into the house via a passageway before Victor can find her.

Millie goes to Victor's forge. Bill fired it up because Victor says that he wants to capture Millie's beauty in bronze. She refuses, returns to her room and finds Dorothy there. She has a present for Millie - the mask from the nightmare.

Victor asks Bill if Millie reminds him of 'our Japanese friend'. Bill wonders aloud what happened to the woman but Victor only says that she was 'a little bitch' who 'actually thought she was immortal'. Victor gives Bill an old painting of Dorothy, who used to be his model. Accepting it, Bill asks why Victor has stayed married to Dorothy for so long. Victor says that he needs her money, adding that Dorothy never wanted Bill.

John phones Millie, who pleads with him to come back. But John's car has broken down and she has to wait while Bill fetches him. Dorothy asks Bill if he really wanted to marry her. When he says that they will discuss it later, Dorothy picks up a straight razor and heads for her private 'cave' in the mine.

Victor convinces Millie to pose, hypnotising her in the flickering light of the burning forge. Back at the studio, he sacks Marcia. She tries to warn Millie about Victor, then goes to her room. Someone knocks and when Marcia opens the door, the person throws acid in her face, disfiguring her and killing her.

Victor makes a pass at Millie in his studio, kissing her thigh while rearranging her kimono. She runs to the passageway with Victor in pursuit. In the mine, she finds Michael's body floating in water and Dorothy dead, her wrists slashed with the razor.

John and Bill return and, not finding Millie or Victor in the house, head for the forge. There, Victor is preparing to pour molten bronze onto Millie to create the sculpture. A disfigured woman then rises from the table upon which Millie was lying. In the ensuing struggle, the woman forces Victor onto the hot coals of the forge. John rushes in just in time to yell 'Millie! No!' as the ghost of the woman Victor killed appears as a laughing face in the flames of his burning head.

After medical personnel remove a covered body, John says that he does not understand what happened. Bill says that everything was caused by 'Chi-San', the Japanese cultist whom Victor turned into his only bronze. The cultists believe that anyone who wears the kimono will be possessed and 'take revenge'. Bill says that Millie did not realise what she was doing as she was 'completely under Chi-San's control' while committing the murders.

John calls Millie's purchase of the kimono a horrible coincidence. Bill says it was no coincidence; 'it was pre-ordained'. The kimono lies on the floor. Only John and Bill are left.

Cast

[edit]- Mike Raven as Victor Clare

- Mary Maude as Millie Davies

- James Bolam as John Davies

- Ronald Lacey as Michael Clare

- Melissa Stribling as Joanna Brent

- John Arnatt as Bill Cartwright

- Betty Alberge as Dorothy Clare

- Judy Matheson as Marcia

- Beth Morris as Jane Clare

- Kenneth Keeling as George Brent

- Me Me Lai as Chi-san

Production

[edit]The film was based on a script by writer Tom Parkinson and television editor Ted Hooker, who had worked together previously on a documentary.[4] The script was completed by August 1970 and the original plan was to raise finance partly through a loan from the National Film Finance Corporation. However they refused, arguging they had financed too many other horror films. Finance was obtained from the independent Glendale Film Productions, the company of Peter Newbrook, who had been assistant cameraman on Dr Zhivago.[1]

Mike Raven thought he had been cast on the strength of his performances in Lust for a Vampire and I Monster but he had been recommended to Parkinson by a colleague who saw him in a documentary, Raggae and thought he "looked like a nutty sculptor".[5] Plans were made for Raven to star in two more films for Glendale if Crucible was a success.[1]

Filming started in July 1971 and took six weeks, four and a half of which took place at Shepperton Studios with the rest on location.[1] Exteriors for Crucible of Terror were shot around St Agnes on the Cornish coast and Hammersmith in London.[6][4] Denis Meikle, who visited the set during filming, later wrote "while allowing for its speed of execution and necessary economies of scale, it nevertheless seemed like an amateur affair."[4]

The budget was 'allegedly £100,000'[7] part of which was put up by the film's star, Michael Raven, 'a British disc jockey turned actor'. Nonetheless, the film was 'not financially successful'.[8]

Crucible of Terror was the first film directed by Ted Hooker.[9]

Distribution

[edit]Crucible of Terror played in theatres in the UK on a double-bill with Lady Frankenstein, both of which carried X-certificates.[10] The X cert prohibited the exhibition of the film to people under age 18.[11]

Although film historian John Hamilton writes that because 'the American market was already flooded with low-budget British films, Crucible of Terror was not deemed worthy of a US release and its failure was assured',[7] film critic Gary A. Smith notes a US running time of 79 minutes, compared to the 91 minutes of the UK version, implying that there was an American release, which he places in 1972.[12] As well, an American film poster shows that the film carried a theatrical M rating, which meant it was intended for 'mature' audiences, although no minimum age was specified as being 'mature'. There is no date on the poster, however, nor does it note whether Crucible of Terror was on a double-bill.[13][14] (Note: the 'M' rating in the US was in use from 1968 to 1970, when it was replaced with the 'GP' rating. The poster in question is probably of Australian origin).

The film was distributed theatrically in the UK in 1972 by Scotia-Barber and at unspecified dates in Australia by Filmways Australasian Distributors. It was also shown in theatres in West Germany, as well as in Japan, Spain, Italy and Turkey. It has been released on VHS and DVD at least 12 times between 1985 and 2016.[15][16] The film was retitled Unholy Terror for its initial release on VHS in the US.[17]

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]The film was a financial failure.[1] Raven made no more films for Glendale. However, he got along well with Parkinson and they later made Disiple of Death together.[5]

Critical

[edit]The Monthly Film Bulletin wrote: "A modest but enjoyable variation on the old House of Wax theme, Ted Hooker's feature debut offers some pleasant location footage of Cornwall and good supporting performances from Ronald Lacey and Melissa Stribling to make up for a fairly negligible script and the awkwardness of the leads. Mike Raven is obviously able to convey charm and intelligence, but he is embarrassingly miscast as a tempestuous artist, while for much of the time the plot consists of a predictable series of murders in which the protagonist is just out frame. But the opening and closing sequences, in which Raven mixes numerous shining waxes and plasters in his glowing Cornish foundry before pouring molten bronze over his victim, are handled with a nice sense of atmosphere. And although the nominally 'occult' ending is actually closer to the level of Agatha Christie, at least it is not easily guessable."[18]

Film critic Kim Newman describes the film as being 'part of the marginal cinema, where double-bill-fillers can be sold for either sex or violence' and 'where nothing else matters', noting that 'the girls are mostly pretty and disposable'. However, Newman goes on to write that 'these films, intentionally or not, manage to locate their horrors in a recognisable, seedy British setting, otherwise unexplored in the movies'.[19]

Smith calls Crucible of Terror 'unpleasant and unmemorable'[12] while film historian Phil Hardy takes the opposite position, writing that it is a 'pleasantly eccentric variation on the house-of-wax theme'. Hardy goes on to say that 'For its climax, the picture shifts into a dreamlike atmosphere, with the mad artist mixing multicoloured concoctions in his cave studio suffused with the glow of the menacing furnace'.[9]

Hamilton says that the film's narrative is 'hopelessly muddled' and that 'the script requires the victims to die in isolation, usually after declaring a desire to leave, which allows the survivors to carry on as if nothing was wrong'. He also criticises some of the actors for 'hamming it up outrageously' whilst others 'give the distinct impression [they] would rather be somewhere else'. On the other hand, Hamilton notes that the 'camerawork makes the barren Cornish landscape look suitably chilly and menacing'. Despite that, even if the budget were £100,000 'on screen it looks far less', he writes.[7]

TV Guide magazine has given Crucible of Terror one out of five stars.[citation needed]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Meikle, Denis (June 1995). "Never more..." Hammer Horror. pp. 17–18.

- ^ "Crucible of Terror". British Film Institute Collections Search. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ BFI.org

- ^ a b c Meikle, Denis. "The Man in Black: A Memoir of Mike Raven". Denis Meikle.

- ^ a b Knight, Chris (Fall 1973). "Interview with Mike Raven". Cinefantastique. p. 45.

- ^ Pykett, Derek (2008). British Horror Film Locations. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co. Inc. p. 144. ISBN 9780786433292.

- ^ a b c Hamilton, John (2014). X-Cert 2: The British Independent Horror Film 1971-1983. East Sussex, England, UK: Hemlock Books Ltd. pp. 60–66. ISBN 9780957535282.

- ^ Hutchings, Peter (2008). The A to Z of Horror Cinema. Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press. p. 258. ISBN 9780810868878.

- ^ a b Hardy, Phil, ed. (1986). The Encyclopedia of Horror Movies. NY: Harper & Row Publishers. p. 230. ISBN 0060550503.

- ^ "Crucible of Terror/Lady Frankenstein poster". Original Poster. Retrieved 6 March 2019.

- ^ "The 1970s". British Board of Film Classification. Retrieved 7 March 2019.

- ^ a b Smith, Gary A. (2000). Uneasy Dreams: The Golden Age of British Horror Films 1956-1976. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co. Inc. p. 60. ISBN 0786426616.

- ^ "Crucible of Horror/Glendale 1971". Monster Movie Music. Archived from the original on 27 September 2016. Retrieved 7 March 2019.

- ^ "History of Ratings". Film Ratings. Retrieved 7 March 2019.

- ^ "Release Information". Internet Movie Data Base. Retrieved 6 March 2019.

- ^ "Company Credits". Internet Movie Data Base. Retrieved 6 March 2019.

- ^ "Unholy Terror". DVD Compare. Archived from the original on 7 October 2015. Retrieved 6 March 2019.

- ^ "Crucible of Terror". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 39 (456): 69. 1 January 1972. ProQuest 1305829450 – via ProQuest.

- ^ Newman, Kim (2011). Nightmare Movies: Horror on the Screen Since the 1960s. London: Bloomsbury. p. 35. ISBN 9781408805039.

External links

[edit]- Crucible of Terror at IMDb

- Crucible of Terror at BFI

- Crucible of Terror at Letterbox DVD

- 1971 films

- 1970s slasher films

- 1971 horror films

- 1970s ghost films

- British slasher films

- Films shot at Shepperton Studios

- Films shot in London

- Films shot in Cornwall

- Films set in London

- Films set in Cornwall

- Films about artists

- Films about spirit possession

- 1970s English-language films

- 1970s British films

- English-language horror films