Diogenes or the Isthmian Oration

Diogenes or the Isthmian Oration (Ancient Greek: Διογένης ἢ Ἰσθμικός, romanized: Diogenēs e Isthmikos, Oration 9 in modern corpora) is a short speech delivered by Dio Chrysostom between AD 82 and 96,[1] which describes the behaviour of the Cynic philosopher Diogenes of Sinope at the Isthmian Games. It emphasises the emptiness of athletic achievement and the superiority of a Cynic lifestyle. The oration forms a pair with the On Virtue, which is presented as a speech delivered by Diogenes at the Isthmian Games.

Background

[edit]

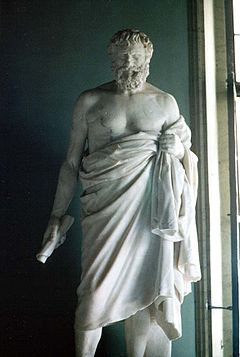

The fourth-century BC philosopher Diogenes founded the Cynic school of philosophy after being exiled from his hometown of Sinope. He was famous for his very ascetic lifestyle, living outdoors and going without shoes or clothes. Dio Chrysostom was exiled by the Emperor Domitian in AD 82 and, according to his 13th oration, On his Banishment, he then adopted the guise of a Cynic philosopher and travelled Greece and the Black Sea, delivering orations like this one.

Summary

[edit]The speech opens with Dio's explanation of why Diogenes attended the Isthmian Games: festivals were the occasion when human stupidity (anoia) was most visible, so he was obliged to attend, as a doctor is obliged to go where the most sick people are found. But Diogenes himself said that he was like a dog watching over its drunken master (1-4).

The rest of the speech deals with Diogenes' conduct at the Games. This is generally irreverent, with particular venom reserved for those who give themselves airs. Dio compares Diogenes at the Games to Odysseus among the suitors, "a king and master in fact, wearing the costume of a beggar" (8-9). First, Diogenes crowns himself with a pine wreath (the prize awarded to victors at the Isthmian Games) and when the organisers of the Games demand that he remove the wreath, he responds that he is more worthy than athletes because he is a victor over hardships, vices, and especially over pleasure (hedone), while athletes are merely people "who eat the most meat" (10-13). Next, Diogenes confronts a jubilant victor in the stadion race and tells him that he has nothing to be proud of: speed is only a sign of cowardice (deilia), Heracles and Achilles were actually both very slow-moving, his victory was very close so he is only better than his competitors "by one step," plenty of animals are still much faster than him, and there is nothing more to be proud of in being the fastest human than there would be in being the fastest ant. Through this kind of behaviour, Diogenes deflated egos "just as doctors pierce and lance boils and abscesses" (14-21). Finally, when two horses get into a fight and one of them drives the other off, Diogenes "announces the other as an Isthmian victor, because it had won at kicking." At this, the people applaud, and many of the poorer visitors decide to leave the Games (22).

Analysis

[edit]A number of shared themes and images suggest that this oration and On Virtue were written as a pair around the same time. For example, both compare the Cynic philosopher to a doctor and a dog, and emphasise that large festivals are good occasions for Cynics to proselytise.[3] Dio's presentation of athleticism in this oration and On Virtue is very negative.[4] Jason König draws connections to negative depictions of athletic training in Lucian's Anacharsis and Seneca's Letters 15 and 80.[5] In this oration, as in those authors, athletics is presented as an empty waste of time.[6] By contrast, in Melancomas I and II, Dio presents athletic training as a model for the Cynic's pursuit of virtue.[7]

Editions

[edit]- Hans von Arnim, Dionis Prusaensis quem uocant Chrysostomum quae exstant omnia (Berlin, 1893–1896).

- Cohoon, J. W. (1932). Dio Chrysostom, I, Discourses 1–11. Princeton: Harvard University Press, Loeb Classical Library. ISBN 9780674992832. Retrieved 4 January 2023.

References

[edit]- ^ Cohoon 1932, p. 375.

- ^ Christopher H. Hallett, (2005), The Roman Nude: Heroic Portrait Statuary 200 BC–AD 300, p. 294. Oxford University Press

- ^ Cohoon 1932, p. 401.

- ^ König 2005, p. 141.

- ^ König 2005, p. 136-138, 157.

- ^ König 2005, p. 136-142.

- ^ König 2005, p. 142.

Bibliography

[edit]- König, Jason (2005). Athletics and Literature in the Roman Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521838450.

External links

[edit]- Full text of the speech on LacusCurtius