Elizabethan literature

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2014) |

Elizabethan literature refers to bodies of work produced during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I (1558–1603), and is one of the most splendid ages of English literature.[1]

Elizabeth I presided over a vigorous culture that saw notable accomplishments in the arts, voyages of discovery, the "Elizabethan Settlement" that created the Church of England, and the defeat of military threats from Spain. [2]

During her reign a London-centred culture, both courtly and popular, produced great poetry and drama. English playwrights combined the influence of the Medieval theatre with the Renaissance's rediscovery of the Roman dramatists, Seneca, for tragedy, and Plautus and Terence, for comedy. Italy was an important source for Renaissance ideas in England and the linguist and lexicographer John Florio (1553–1625), whose father was Italian, a royal language tutor at the Court of James I, who had furthermore brought much of the Italian language and culture to England. He also translated the works of Montaigne from French into English.[3]

Prose

Two of the most important Elizabethan prose writers were John Lyly (1553 or 1554 – 1606) and Thomas Nashe (November 1567 – c. 1601). Lyly is an English writer, poet, dramatist, playwright, and politician, best known for his books Euphues: The Anatomy of Wit (1578) and Euphues and His England (1580). Lyly's mannered literary style, originating in his first books, is known as euphuism. Lyly must also be considered and remembered as a primary influence on the plays of William Shakespeare, and in particular the romantic comedies. Lyly's play Love's Metamorphosis is a large influence on Love's Labour's Lost,[4] and Gallathea is a possible source for other plays.[5] Nash is considered the greatest of the English Elizabethan pamphleteers.[6] He was a playwright, poet, and satirist, who is best known for his novel The Unfortunate Traveller.[7]

George Puttenham (1529–1590) was a 16th-century English writer and literary critic. He is generally considered to be the author of the influential handbook on poetry and rhetoric, The Arte of English Poesie (1589).

Poetry

Italian literature was an important influence on the poetry of Thomas Wyatt (1503–42), one of the earliest English Renaissance poets. He was responsible for many innovations in English poetry, and alongside Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey (1516/1517–47) introduced the sonnet from Italy into England in the early 16th century.[8][9][10] Wyatt's professed object was to experiment with the English tongue, to civilise it, to raise its powers to those of its neighbours.[8] While a significant amount of his literary output consists of translations and imitations of sonnets by the Italian poet Petrarch, he also wrote sonnets of his own. Wyatt took subject matter from Petrarch's sonnets, but his rhyme schemes make a significant departure. Petrarch's sonnets consist of an "octave", rhyming abba abba, followed, after a turn (volta) in the sense, by a sestet with various rhyme schemes, however his poems never ended in a rhyming couplet. Wyatt employs the Petrarchan octave, but his most common sestet scheme is cddc ee. This marks the beginnings of English sonnet with 3 quatrains and a closing couplet.[11]

In the later 16th century, English poetry was characterised by elaboration of language and extensive allusion to classical myths. The most important poets of this era include Edmund Spenser and Sir Philip Sidney. Elizabeth herself, a product of Renaissance humanism, produced occasional poems such as On Monsieur’s Departure and The Doubt of Future Foes.

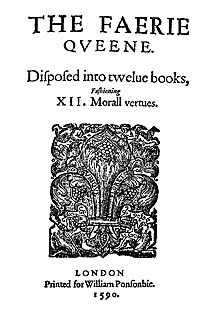

Edmund Spenser (c. 1552–99) was one of the most important poets of this period, author of The Faerie Queene (1590 and 1596), an epic poem and fantastical allegory celebrating the Tudor dynasty and Elizabeth I. Another major figure, Sir Philip Sidney (1554–86), was an English poet, courtier and soldier, and is remembered as one of the most prominent figures of the Elizabethan Age. His works include Astrophel and Stella, The Defence of Poetry, and The Countess of Pembroke's Arcadia. Poems intended to be set to music as songs, such as by Thomas Campion (1567–1620), became popular as printed literature was disseminated more widely in households. See English Madrigal School.

Shakespeare also popularized the English sonnet, which made significant changes to Petrarch's model. Poems intended to be set to music as songs, such as those by Thomas Campion, became popular as printed literature was disseminated more widely in households. See English Madrigal School.

Changes to the canon

While the canon of Renaissance English poetry of the 16th has always been in some form of flux, it is only towards the late 20th century that concerted efforts were made to challenge the canon. Questions that once did not even have to be made, such as where to put the limitations of periods, what geographical areas to include, what genres to include, what writers and what kinds of writers to include, are now central.

The central figures of the Elizabethan canon are Edmund Spenser, Sir Philip Sidney, Christopher Marlowe, William Shakespeare, and Ben Jonson. There have been few attempts to change this long established list because the cultural importance of these six is so great that even re-evaluations on grounds of literary merit has not dared to dislodge them from the curriculum. Edmund Spenser had a significant influences on 17th-century poetry. Spenser was the primary English influence on John Milton.

In the 18th century interest in Elizabethan poetry was rekindled through the scholarship of Thomas Warton and others.

The Lake Poets and other Romantics, at the beginning of the 19th century, were well-read in Renaissance poetry. However, the canon of Renaissance poetry was formed only in the Victorian period, with anthologies like Palgrave's Golden Treasury. A fairly representative idea of the "Victorian canon" is also given by Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch's Oxford Book of English Verse (1919). The poems from this period are largely songs and apart from the major names, one sees the two pioneers Sir Thomas Wyatt and the Earl of Surrey, and a scattering of poems by other writers of the period. However, the authors of many poems are anonymous. Some poems, such as Thomas Sackville's Induction to the Mirror for Magistrates, were highly regarded (and therefore "in the canon") but they were omitted from the anthology as non-lyric.

In the 20th century T. S. Eliot's many essays on Elizabethan subjects were mainly concerned with Elizabethan theatre, but he also attempted to bring back long-forgotten poets to general attention, like Sir John Davies, whose cause he championed in an article in The Times Literary Supplement in 1926 (republished in On Poetry and Poets, 1957).

The American critic Yvor Winters suggested in 1939, an alternative canon of Elizabethan poetry.[12] In this canon he excludes the famous representatives of the Petrarchan school of poetry, represented by Sir Philip Sidney and Edmund Spenser, and instead turns his eye to a Native or Plain Style anti-Petrarchan movement, which he claims has been overlooked and undervalued. The most underrated member of this movement he deems to have been George Gascoigne (1525–1577), who "deserves to be ranked...among the six or seven greatest lyric poets of the century, and perhaps higher".[13] Other members were Sir Walter Raleigh (1552–1618), Thomas Nashe (1567–1601), Barnabe Googe (1540–1594), and George Turberville (1540–1610).

Characteristic of this movement is that a poem has

- a theme usually broad, simple, and obvious, even tending toward the proverbial, but usually a theme of some importance, humanly speaking; a feeling restrained to the minimum required by the subject; a rhetoric restrained to a similar minimum, the poet being interested in his rhetoric as a means of stating his matter as economically as possible, and not, as are the Petrarchans, in the pleasures of rhetoric for its own sake. There is also in the school a strong tendency towards aphoristic statement.[14]

Both Eliot and Winters were very much in favour of the established canon. Towards the end of the 20th century however, the established canon was criticized, especially by those who wished to expand it to include, for example, more women writers. [15]

Theatre

The Italian Renaissance had rediscovered the ancient Greek and Roman theatre. This revival of interest was instrumental in the development of the new drama, which was then beginning to make apart from the old mystery and miracle plays of the Middle Ages. The Italians were inspired by Seneca (a major tragic playwright and philosopher, the tutor of Nero) and by Plautus (whose comic clichés, especially that of the boasting soldier, had a powerful influence during the Renaissance and thereafter). However, the Italian tragedies embraced a principle contrary to Seneca's ethics: showing blood and violence on the stage. In Seneca's plays such scenes were only acted by the characters.

During the reign of Elizabeth I (1558–1603) and then James I (1603–25), in the late 16th and early 17th century, a London-centred culture, that was both courtly and popular, produced great poetry and drama. The English playwrights were intrigued by Italian model: a conspicuous community of Italian actors had settled in London. The linguist and lexicographer John Florio (1553–1625), whose father was Italian, was a royal language tutor at the Court of James I, and a possible friend and influence on William Shakespeare, had brought much of the Italian language and culture to England. He was also the translator of Montaigne into English. The earliest Elizabethan plays include Gorboduc (1561), by Sackville and Norton, and Thomas Kyd's (1558–94) revenge tragedy The Spanish Tragedy (1592). Highly popular and influential in its time, The Spanish Tragedy established a new genre in English literature theatre, the revenge play or revenge tragedy. Its plot contains several violent murders and includes as one of its characters a personification of Revenge. The Spanish Tragedy was often referred to, or parodied, in works written by other Elizabethan playwrights, including William Shakespeare, Ben Jonson, and Christopher Marlowe. Many elements of The Spanish Tragedy, such as the play-within-a-play used to trap a murderer and a ghost intent on vengeance, appear in Shakespeare's Hamlet. Thomas Kyd is frequently proposed as the author of the hypothetical Ur-Hamlet that may have been one of Shakespeare's primary sources for Hamlet.

Jane Lumley (1537–1578) was the first person to translate Euripides into English. Her translation of Iphigeneia at Aulis is the first known dramatic work by a woman in English.[16]

William Shakespeare (1564–1616) stands out in this period both as a poet and playwright. Shakespeare wrote plays in a variety of genres, including histories, tragedies, comedies and the late romances, or tragicomedies. His early classical and Italianate comedies, like A Comedy of Errors, containing tight double plots and precise comic sequences, give way in the mid-1590s to the romantic atmosphere of his greatest comedies,[17] A Midsummer Night's Dream, Much Ado About Nothing, As You Like It, and Twelfth Night. After the lyrical Richard II, written almost entirely in verse, Shakespeare introduced prose comedy into the histories of the late 1590s, Henry IV, parts 1 and 2, and Henry V. This period begins and ends with two tragedies: Romeo and Juliet, and Julius Caesar, based on Sir Thomas North's 1579 translation of Plutarch's Parallel Lives, which introduced a new kind of drama.[18]

Shakespeare's career continued into the Jacobean period, and in the early 17th century Shakespeare wrote the so-called "problem plays", Measure for Measure, Troilus and Cressida, and All's Well That Ends Well, as well as a number of his best known tragedies, including Hamlet, Othello, Macbeth, King Lear and Anthony and Cleopatra.[19] The plots of Shakespeare's tragedies often hinge on such fatal errors or flaws, which overturn order and destroy the hero and those he loves.[20] In his final period, Shakespeare turned to romance or tragicomedy and completed three more major plays: Cymbeline, The Winter's Tale and The Tempest, as well as the collaboration, Pericles, Prince of Tyre. Less bleak than the tragedies, these four plays are graver in tone than the comedies of the 1590s, but they end with reconciliation and the forgiveness of potentially tragic errors.[21] Shakespeare collaborated on two further surviving plays, Henry VIII and The Two Noble Kinsmen, probably with John Fletcher.[22]

Other important figures in the Elizabethan theatre include Christopher Marlowe, and Thomas Dekker.

Marlowe's (1564–1593) subject matter is different from Shakespeare's as it focuses more on the moral drama of the Renaissance man than any other thing. Drawing on German folklore, Marlowe introduced the story of Faust to England in his play Doctor Faustus (c. 1592), about a scientist and magician who, obsessed by the thirst of knowledge and the desire to push man's technological power to its limits, sells his soul to the Devil. Faustus makes use of "the dramatic framework of the morality plays in its presentation of a story of temptation, fall, and damnation, and its free use of morality figures such as the good angel and the bad angel and the seven deadly sins, along with the devils Lucifer and Mephistopheles."[23]

Thomas Dekker (c.1570–1632) was, between 1598 and 1602, involved in about forty plays, usually in collaboration. He is particularly remembered for The Shoemaker's Holiday (1599), a work where he appears to be the sole author. Dekker is noted for his "realistic portrayal of daily London life and for "his sympathy for the poor and oppressed".[24]

Robert Greene (c.1558 – 1592) was another popular dramatist but he is now best known for a posthumous pamphlet attributed to him, Greenes, Groats-worth of Witte, bought with a million of Repentance, widely believed to contain an attack on William Shakespeare.

List of other writers

List of other of the writers born in this period:

- John Donne (1572– 1631) -- see Jacobean Literature

- Ben Jonson (1572 – 1637) -- see Jacobean Literature

- Thomas Middleton (1580 – July 1627) -- see Jacobean Literature

- John Webster (c. 1580 – c. 1634) -- see Jacobean Literature

See also

References

- ^ "Elizabethan Literature", Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ "Elizabeth I, Queen of England 1533–1603", Anthology of British Literature, vol. A (concise ed.), Petersborough: Broadview, 2009, p. 683.

- ^ Frances A. Yates, The life of an Italian in Shakespeare’s England.

- ^ Kerrigan, J. ed. "Love's Labours Lost", New Penguin Shakespeare, Harmondsworth 1982, ISBN 0-14-070738-7;

- ^ "John Lilly and Shakespeare", by C. C. Hense in the Jahrbuch der deutschen Shakesp. Gesellschaft, vols. vii and viii (1872, 1873).

- ^ Nicholl, Charles (8 March 1990). "'Faustus' and the Politics of Magic". London Review of Books. pp. 18–19. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- ^ John O‘Connell (28 February 2008). "Sex and books: London's most erotic writers". Time Out. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ a b Tillyard 1929.

- ^ Burrow 2004.

- ^ Ward et al. 1907–21, p. 3.

- ^ The Norton Anthology of English Literature: Sixteenth/Early Seventeenth Century, Volume B, 2012, p. 647

- ^ Poetry, LII (1939, pp. 258-72, excerpted in Paul. J. Alpers (ed): Elizabethan Poetry. Modern Essays in Criticism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967.

- ^ Poetry, LII (1939, pp. 258-72, excerpted in Paul. J. Alpers (ed): Elizabethan Poetry. Modern Essays in Criticism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967: 98

- ^ Poetry, LII (1939, pp. 258-72, excerpted in Paul. J. Alpers (ed): Elizabethan Poetry. Modern Essays in Criticism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967: 95

- ^ Waller, Gary F. (2013). English Poetry of the Sixteenth Century. London: Routledge. pp. 263–70. ISBN 0582090962. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- ^ Buck, Claire, ed. "Lumley, Joanna Fitzalan (c. 1537–1576/77)." The Bloomsbury Guide to Women's Literature. New York: Prentice Hall, 1992. 764.

- ^ Ackroyd 2006, p. 235.

- ^ Ackroyd 2006, pp. 353, 358; Shapiro 2005, pp. 151–153.

- ^ Bradley 1991, p. 85; Muir 2005, pp. 12–16.

- ^ Bradley 1991, pp. 40, 48.

- ^ Dowden 1881, p. 57.

- ^ Wells et al. 2005, pp. 1247, 1279

- ^ "Christopher Marlowe." Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2013. Web. 6 April 2013. <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/365890/Christopher-Marlowe>.

- ^ The Oxford Companion to English Literature (1996), pp. 266–7.