Eugène Sue

Eugène Sue | |

|---|---|

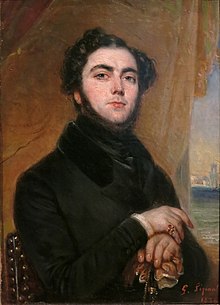

Portrait of Eugene Sue (1835) by François-Gabriel Lépaulle | |

| Born | Joseph Marie Eugène Sue 26 January 1804 Paris |

| Died | 3 August 1857 (aged 53) Annecy-le-Vieux, Kingdom of Sardinia |

| Resting place | Cimetière de Loverchy, Annecy |

| Occupation | Novelist |

| Language | French |

| Nationality | French |

| Education | Lycée Condorcet |

| Period | 1830–1857 |

| Literary movement | Romanticism |

| Notable works | The Mysteries of Paris |

| Notable awards | Legion of Honour |

| French and Francophone literature |

|---|

| by category |

| History |

| Movements |

| Writers |

| Countries and regions |

| Portals |

Marie-Joseph "Eugène" Sue (French pronunciation: [ø.ʒɛn sy]; 26 January 1804 – 3 August 1857) was a French novelist. He was one of several authors who popularized the genre of the serial novel in France with his very popular and widely imitated The Mysteries of Paris, which was published in a newspaper from 1842 to 1843.

Early life

He was born in Paris, the son of a distinguished surgeon in Napoleon's army, Jean-Joseph Sue, and is said to have had the Empress Joséphine for godmother. Sue himself acted as surgeon both in the 1823 French campaign in Spain and at the Battle of Navarino (1828). In 1829 his father's death put him in possession of a considerable fortune, and he settled in Paris.

Literary career

His naval experiences supplied much of the materials of his first novels, Kernock le pirate (1830), Atar-Gull (1831), La Salamandre (2 vols., 1832), La Coucaratcha (4 vols., 1832–1834), and others, which were composed at the height of the Romantic movement of 1830. In the quasi-historical style he wrote Jean Cavalier, ou Les Fanatiques des Cevennes (4 vols., 1840) and Latréaumont (2 vols., 1837). His Mathilde (1841) contains the first known expression of the popular proverb "La vengeance se mange très-bien froide", lately expressed in English as "Revenge is a dish best served cold".[1]

He was strongly affected by the socialist ideas of the day, and these prompted his most famous works, the "anti-Catholic" novels: The Mysteries of Paris (Les Mystères de Paris) (published in Journal des débats from 19 June 1842 until 15 October 1843) and The Wandering Jew (Le Juif errant; 10 vols., 1844–1845), which were among the most popular specimens of the serial novel.[2] These works depicted the intrigues of the nobility and the harsh life of the underclass to a wide public. Les Mystères de Paris spawned a class of imitations all over the world, the city mysteries.

He followed up with some singular though not very edifying books: Les Sept pêchés capitaux (16 vols., 1847–1849), which contained stories to illustrate each of the seven deadly sins, Les Mystères du peuple (1849–1856), which was suppressed by the censor in 1857, and several others, all on a very large scale, though the number of volumes gives an exaggerated idea of their length. Some of his books, among them The Wandering Jew and The Mysteries of Paris, were dramatized by himself, usually in collaboration with others. His period of greatest success and popularity coincided with that of Alexandre Dumas, with whom he has been compared.

According to Umberto Eco, parts of Sue's book Les Mystères du peuple served as a source for Maurice Joly in his Dialogue in Hell Between Machiavelli and Montesquieu, a book attacking Napoleon III and his political ambitions. The two are depicted in Will Eisner's cartoon book The Plot, co-authored with Eco.[3]

Political career

After the French Revolution of 1848, he was elected to the Legislative Assembly from the Paris-Seine constituency in April 1850. He was exiled from Paris in consequence of his protest against the French coup d'état of 1851. This exile stimulated his literary production. Sue died in Annecy-le-Vieux, Savoy on August 3, 1857 and was buried at the Cimetière de Loverchy (Annecy) in the Non-Catholic's Carré des "Dissidents".

Legacy

- Rue Eugène Sue in the 18th arrondissement of Paris near the Marcadet-Poissonniers station of the Paris Métro, not far from Montmartre and the Sacré-Cœur.

- Calle Eugenio Sue in Polanco, Mexico City.

- Sue is a character in Umberto Eco's 2010 novel The Prague Cemetery.

- United States socialist Eugene Victor Debs was named after Eugene Sue and Victor Hugo.

- In Thomas Pynchon's 2006 novel Against the Day, an intelligent dog named Pugnax enjoys reading Sue.

References

- ^ Language Log. University of Pennsylvania

- ^ McGreevy, John (2004). Catholicism and American Freedom: A History. W. W. Norton. pp. 22–23. ISBN 978-0-393-34092-1.

- ^ Eco, Umberto (1994), "Fictional Protocols", Six Walks in the Fictional Woods, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, p. 135, ISBN 0-674-81051-1

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Eugène Sue". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

- Wandering Jew and Wandering Jewess dramatic screenplay adaptations by Robert Douglas Manning ISBN 978-1-895507-03-4

- Eugène Sue - Mini Biography Find A Grave

- Works by Eugène Sue at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Eugène Sue at the Internet Archive

- Works by Eugène Sue at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)