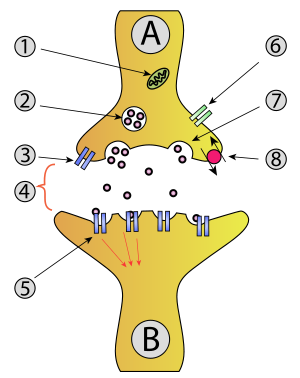

Exocytosis

1. Mitochondrion

2. Synaptic vesicle with neurotransmitters

3. Autoreceptor

4. Synapse with neurotransmitter released (serotonin)

5. Postsynaptic receptors activated by neurotransmitter (induction of a postsynaptic potential)

6. Calcium channel

7. Exocytosis of a vesicle

8. Recaptured neurotransmitter

Exocytosis (/ˌɛksoʊsaɪˈtoʊsɪs/[1][2]) is a form of active transport in which a cell transports molecules (such as proteins) out of the cell (exo- + cytosis) by expelling them in an energy-using process. Exocytosis and its counterpart, endocytosis, are used by all cells because most chemical substances important to them are large polar molecules that cannot pass through the hydrophobic portion of the cell membrane by passive means.

In exocytosis, membrane-bound secretory vesicles are carried to the cell membrane, and their contents (water-soluble molecules such as proteins) are secreted into the extracellular environment. This secretion is possible because the vesicle transiently fuses with the outer cell membrane.

Exocytosis is also a mechanism by which cells are able to insert membrane proteins (such as ion channels and cell surface receptors), lipids, and other components into the cell membrane. Vesicles containing these membrane components fully fuse with and become part of the outer cell membrane.

History

The term was proposed by De Duve in 1963.[3]

Types

In eukaryotic organisms there are two types of exocytosis: 1) Ca2+ triggered non-constitutive (i.e., regulated exocytosis) and 2) non-Ca2+ triggered constitutive (i.e., non-regulated). Ca2+ triggered non-constitutive exocytosis requires an external signal, a specific sorting signal on the vesicles, a clathrin coat, as well as an increase in intracellular calcium. Exocytosis in neuronal chemical synapses is Ca2+ triggered and serves interneuronal signalling. Constitutive exocytosis is performed by all cells and serves the release of components of the extracellular matrix or delivery of newly synthesized membrane proteins that are incorporated in the plasma membrane after the fusion of the transport vesicle.

Vesicular exocytosis in prokaryote gram negative microbes is a third mechanism and latest finding in exocytosis. Herein, periplasm of gram negative microbes is pinched off as bacterial outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) for translocating microbial biochemical signals into eukaryotic host cells[4] or other microbes located nearby,[5] accomplishing control of the secreting microbe on its environment - including invasion of host, endotoxemia, competing with other microbes for nutrition, etc. This finding of membrane vesicle trafficking occurring at the host-pathogen interface also dispels the myth that exocytosis is purely a eukaryotic cell phenomenon.[6]

Steps

Five steps are involved in exocytosis:

Vesicle trafficking

Certain vesicle-trafficking steps require the transportation of a vesicle over a moderately small distance. For example, vesicles that transport proteins from the Golgi apparatus to the cell surface area, will be likely to use motor proteins and a cytoskeletal track to get closer to their target. Before tethering would have been appropriate, many of the proteins used for the active transport would have been instead set for passive transport, because the Golgi apparatus does not require ATP to transport proteins. Both the actin- and the microtubule-base are implicated in these processes, along with several motor proteins. Once the vesicles reach their targets, they come into contact with tethering factors that can restrain them.

Vesicle tethering

It is useful to distinguish between the initial, loose tethering of vesicles to their objective from the more stable, packing interactions. Tethering involves links over distances of more than about half the diameter of a vesicle from a given membrane surface (>25 nm). Tethering interactions are likely to be involved in concentrating synaptic vesicles at the synapse.

Tethered vesicles are also involved in regular cell's transcription processes.

Vesicle docking

Secretory vesicles transiently dock at the cell plasma membrane, preceding the formation of a tight t-/v-SNARE complex, leading to priming and the establishment of continuity between the opposing bilayers.

Vesicle priming

In neuronal exocytosis, the term priming has been used to include all of the molecular rearrangements and ATP-dependent protein and lipid modifications that take place after initial docking of a synaptic vesicle but before exocytosis, such that the influx of calcium ions is all that is needed to trigger nearly instantaneous neurotransmitter release. In other cell types, whose secretion is constitutive (i.e. continuous, calcium ion independent, non-triggered) there is no priming.

Vesicle fusion

Transient vesicle fusion is driven by SNARE proteins, resulting in release of vesicle contents into the extracellular space (or in case of neurons in the synaptic cleft).

The merging of the donor and the acceptor membranes accomplishes three tasks:

- The surface of the plasma membrane increases (by the surface of the fused vesicle). This is important for the regulation of cell size, e.g., during cell growth.

- The substances within the vesicle are released into the exterior. These might be waste products or toxins, or signaling molecules like hormones or neurotransmitters during synaptic transmission.

- Proteins embedded in the vesicle membrane are now part of the plasma membrane. The side of the protein that was facing the inside of the vesicle now faces the outside of the cell. This mechanism is important for the regulation of transmembrane and transporters.

Vesicle Retrieval

Retrieval of synaptic vesicles occurs by endocytosis. Some synaptic vesicles are recycled without a full fusion into the membrane (kiss-and-run fusion), while others require a complete reformation of synaptic vesicles from the membrane by a specialized complex of proteins (clathrin). Non-constitutive exocytosis and subsequent endocytosis are highly energy expending processes, and thus, are dependent on mitochondria.[7]

Examination of cells following secretion using electron microscopy demonstrate increased presence of partially empty vesicles following secretion. This suggested that during the secretory process, only a portion of the vesicular content is able to exit the cell. This could only be possible if the vesicle were to temporarily establish continuity with the cell plasma membrane, expel a portion of its contents, then detach, reseal, and withdraw into the cytosol (endocytose). In this way, the secretory vesicle could be reused for subsequent rounds of exo-endocytosis, until completely empty of its contents.[8]

References

- ^ "Exocytosis". Oxford Dictionaries UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. n.d. Retrieved 2016-01-21.

- ^ "Exocytosis". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.

- ^ Rieger, R.; Michaelis, A.; Green, M.M. 1991. Glossary of Genetics. Classical and Molecular (Fifth edition). Springer-Verlag, Berlin, [1].

- ^ YashRoy R C (1993) Eelectron microscope studies of surface pili and vesicles of Salmonella 3,10:r:- organisms. Indian Journal of Animal Sciences, vol. 63, pp. 99-102.https://www.researchgate.net/publication/230817087_Electron_microscope_studies_of_surface_pilli_and_vesicles_of_Salmonella_310r-_organisms?ev=prf_pub

- ^ Kadurugamuwa, J L; Beveridge, T J (1996). "Bacteriolytic effect of membrane vesicles from Pseudomonas aeruginosa on other bacterial including pathogens: conceptually new antibiotics". Journal of Bacteriology. 178 (10): 2767–2774. PMC 178010. PMID 8631663.

- ^ YashRoy, R.C. (1998). "Discovery of vesicular exocytosis in procaryotes and its role in Salmonella invasion" (PDF). Current Science. 75 (10): 1062–1066.

- ^ Ivannikov, M.; et al. (2013). "Synaptic vesicle exocytosis in hippocampal synaptosomes correlates directly with total mitochondrial volume". J. Mol. Neurosci. 49 (1): 223–230. doi:10.1007/s12031-012-9848-8. PMID 22772899.

- ^ Boron, WF; Boulpaep, EL (2012), Medical Physiology. A Cellular and Molecular Approach, vol. 2, Philadelphia: Elsevier

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help)

External links

- Exocytosis at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)