Fairlie locomotive

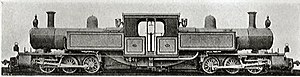

A Fairlie is a type of articulated steam locomotive that has the driving wheels on bogies. The locomotive may be double-ended (a double Fairlie) or single ended (a single Fairlie). Fairlies are most associated with the Ffestiniog Railway in Wales.

Overview

The Fairlie was invented and patented by the Scottish engineer Robert F. Fairlie in 1864. He had become convinced that the conventional pattern of locomotive was seriously deficient; they wasted weight on unpowered wheels (the maximum tractive effort a locomotive can exert is a function of the weight on its driving wheels) and on a tender that did nothing but carry fuel and water without contributing to the locomotive's adhesive weight. Furthermore, the standard locomotive had a front and back, and was not intended for prolonged driving in reverse, thus requiring a turntable or wye at every terminus.

Fairlie's answer was a double-ended steam locomotive, carrying all its fuel and water aboard the locomotive and with every axle driven. The double-ended part was accomplished by having two boilers on the locomotive, joined back-to-back at the firebox ends, with the smokeboxes at the ends of the locomotive (looking fairly conventional, until you realise the locomotive is two-faced, Janus-like). In Fairlie's original design the boilers shared a common firebox, but with separate water spaces; it was found that this did not work as well as expected, and on later locomotives the fireboxes were partitioned into two.

The locomotive driver (US: engineer) worked on one side of the locomotive, and the fireman on the other; the joined fireboxes separated them. There were, of course, controls at both ends of the central cab to allow the locomotive to be driven equally well in both directions.

Underneath, the locomotive was supported on two swivelling powered bogies (US: trucks), with all wheels driven; smaller locomotives had four-wheel bogies, while larger had six-wheel. The cylinders on each power bogie pointed outward, towards the locomotive end. Steam was delivered to the cylinders via flexible tubing. Couplers and buffers (where fitted) were sometimes mounted on the bogies, not on the locomotive frame, so that they swivelled with the curvature of the track.

Fuel and water were carried on the locomotive, in the form of side tanks beside each boiler for the water, and bunkers for the fuel above them.

Early Fairlie locomotives were rather unsuccessful, examples being built for the Neath and Brecon Railway and for the Queensland Railways in Australia being notably unsuccessful, in the latter case resulting in locomotives being returned to the builder. However, in 1869 Fairlie's company built a locomotive, named Little Wonder (Fairlie was not an individual given to modesty) for the Festiniog Railway (later renamed Ffestiniog), a slate hauler in north Wales, and this one proved to be an outstanding success. Particularly important for a narrow gauge line as small as the Festiniog, whose gauge was the minuscule one of 1 ft 11½ in, was the fact that the Fairlie design meant that the fireboxes and ashpans were not restricted by frame or track width, but only by the overall loading gauge. Little Wonder was such a success that Fairlie offered the Festiniog management a perpetual license to use the Fairlie patent without restriction in return for using the line and the success of its Fairlie locomotives in his publicity. The Ffestiniog, indeed, still uses Fairlie patent locomotives to this day; it has owned seven, of which four are still in running condition. The most recent Fairlie locomotives, Earl of Meirioneth and David Lloyd George, were built in 1979 and 1992 respectively.

Armed with this success, Fairlie sold his invention (and the concept of the narrow gauge railway on which it was based) around the world. Locomotives were built for many British colonies, for Imperial Russia, and even one example for the United States.

The locomotive sold in the US was ordered for the newly built Denver and Rio Grande Railroad in 1872, and was a smaller locomotive with four-wheel bogies, giving it an 0-4-0+0-4-0 configuration. The railroad's experience with the locomotive was typical, and an indication of the fact that, though Fairlie had eliminated several problems of the conventional locomotive, he had introduced new ones of his own.

Most critical was the absence of a tender, meaning that the capacity for fuel and water was very small. A locomotive is already a crowded place, and Fairlie's design gave even less room to place its supplies than a normal tank locomotive, which at least has a space behind the driver's cab to fill. Moreover, the central position of the cab meant that it was hard to add a tender later. As was later the case with Bulleid's Leader class locomotives, limited fuel supplies would not have been a problem if oil had been used as a fuel instead of coal.

Also problematic were the flexible steam pipes to and from the cylinders of each swivelling engine; they were prone to leakage and wasting of power.

The final problem lay in the power bogies; there was a good reason for unpowered wheels on a steam locomotive, in that they served a function of stabilising the locomotive, reducing its tendency to wander or 'hunt' when rolling on straight track, and leading the locomotive into curves and thereby reducing derailments. Fairlies had a tendency to be rough-riding, rough on the track they rode, and more prone to derailment than they should have been.

The only really successful uses of the Fairlie locomotive, other than on the Ffestiniog Railway, were in New Zealand and on a mountainous stretch of the Ferrocaril Mexicano's line between Mexico City and Veracruz, where a total of 49 enormous 0-6-0+0-6-0 Fairlies weighing about 125 tons apiece, imported from England and the largest and most powerful locomotives built there up to that point, were used until the line was electrified in the 1920s.

A variation of the Fairlie that enjoyed some popularity, especially in the United States, was the single Fairlie, essentially half a double Fairlie, with one boiler, a cab at one end, and a single articulated power bogie combined with an unpowered bogie under the cab. This design abandoned the bidirectional nature of the double Fairlie but gained back the ability to have a large bunker and water tank behind the cab, and the possibility of using a trailing tender if necessary. The single conventional boiler made maintenance cheaper and did away with the crew's separation. A fair number were built, especially by Fairlie's licensee in the United States, William Mason, who built 146 or so Mason Bogies.

Fairlie's vision was limited by the limitations of the steam locomotive — its thirst for water and the unbalancing forces of its directly driving pistons – but he did successfully anticipate the form of locomotives for the future. The vast majority of diesel and electric locomotives in the world today follow a form not too dissimilar from Fairlies — two power trucks with all axles driven, and a huge number follow Fairlie's idea of being double-ended, capable of being driven equally well in both directions. Some inventors are limited by the available technology of their day, and it could be said that Fairlie was one.

To see an operating Fairlie today, one must go to Wales and visit the Ffestiniog Railway. Nowhere else in the world do these unique locomotives still run, though two are preserved in New Zealand's South Island: Josephine, a double Fairlie, at Dunedin, and R28, a single Fairlie, at Reefton. One of the Ffestiniog locos, Merddin Emrys, is an 1879 product of the Ffestiniog's own Boston Lodge workshops, and is still going strong over 120 years later.