Fall of Tripoli (1289)

| Siege of Tripoli (1289) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of The Crusades | |||||||||

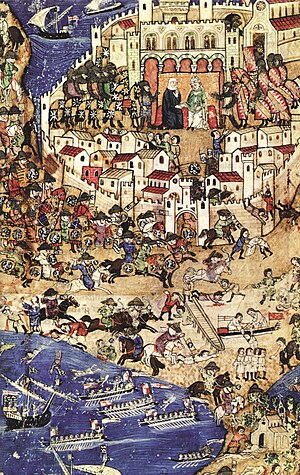

The siege of Tripoli by the Mamluks in 1289. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

Lucia of Tripoli Godefroy de Vendac Mathieu de Clermont Amalric of Tyre | ||||||||

The Fall of Tripoli was the capture and destruction of the Crusader state, the County of Tripoli (in what is modern-day Lebanon), by the Muslim Mamluks. The battle occurred in 1289 and was an important event in the Crusades, as it marked the capture of one of the few remaining major possessions of the Crusaders.

Context

The County of Tripoli, though founded as a Crusader State and predominantly Christian, had been a vassal state of the Mongol Empire since around 1260, when Bohemond VI, under the influence of his father-in-law Hethum I, King of Armenia, preemptively submitted to the rapidly advancing Mongols. Tripoli had provided troops to the Mongols for the 1258 sack of Baghdad, as well as for the 1260 Mongol invasions of Syria, which caused even further friction with the Muslim world.[1]

After the destruction of Baghdad and the capture of Damascus, which were the centers of the Abbasid and Ayyubid caliphates, by the Khan Hulegu, Islamic power had shifted to the Egyptian Mamluks based in Cairo. Around the same time, the Mongols were slowed in their westward expansion by internal conflicts in their thinly spread Empire. The Mamluks took advantage of this to advance northwards from Egypt, and re-establish dominion over Palestine and Syria, pushing the Ilkhans back into Persia. The Mamluks attempted to take Tripoli in the 1271 siege, but were instead frustrated in their goal by the arrival of Prince Edward in Acre that month. They were persuaded to agree to a truce with both Tripoli and Prince Edward, although his forces had been too small to be truly effective.

The Mongols, for their part, had not proven to be staunch defenders of their vassal, the Christian state of Tripoli. Abaqa Khan, the ruler of the Ilkhanate, who had been sent envoys to Europe in an attempt to form a Franco-Mongol alliance against the Muslims, had died in 1282. He was succeeded by Tekuder, a convert to Islam. Under Tekuder's leadership, the Ilkhanate was not inclined to defend vassal Christian territories against Muslim encroachment. This enabled the Mamluks to continue their attacks against the remaining coastal cities which were still under Crusader control.[2]

Tekuder was assassinated in 1284 and replaced by Abaqa's son Arghun, who was more sympathetic to Christianity. He continued his father's communications with Europe towards the possibility of forming an alliance, but still did not show much interest in protecting Tripoli. However, the Mamluks continued to expand their control, conquering Margat in 1285, and Lattakiah in 1287.

The Mamluk Sultan Qalawun still had an official truce with Tripoli, but the Christians afforded him an opportunity to break it. The Christian powers had been pursuing an unwise course. Rather than maintaining a united front against the Muslims, they had fallen into bickering among themselves. The best known example of this was the dispute between the merchant republics of Genoa and Venice. Lucia of Tripoli, ruler of the County of Tripoli, had allied with the Genoese, and was therefore opposed by the Venetians, as well as by Bartolemew Embriaco of Gibelet. Envoys from both Bartolemew and the Venetians had been sent to Alexandria, Egypt to petition for the intervention of the Sultan Qalawun against the Genoese. They suggested to him that the Genoese, if left unchecked, would potentially dominate the Levant and obstruct or eliminate Mamluk trade.[3] Qalawun thus had an excuse to break his truce with Tripoli. He moved north with his army.

The siege

Qalawun started the siege of Tripoli in March 1289, arriving with a sizable army and large catapults. In response, Tripoli's Commune and nobles gave supreme authority to Lucia. In the harbor at the time, there were four Genoese galleys, two Venetian galleys, and a few small boats, some of them Pisan. Reinforcements were sent to Tripoli by the Knights Templar, who sent a force under Geoffrey of Vendac, and the Hospitallers sent a force under Matthew of Clermont. A French regiment was sent from Acre under John of Grailly. King Henry II of Cyprus sent his young brother Amalric with a company of knights and four galleys. Many non-combatants fled to Cyprus.[4]

The Mamluks fired their catapults, two towers soon crumbled under the bombardments, and the defenders hastily prepared to flee. The Mamluks overran the crumbling walls, and captured the city on April 26, marking the end of an uninterrupted Christian rule of 180 years, the longest of any of the major Frankish conquests in the Levant.[5] Lucia managed to flee to Cyprus, with two Marshals of the Orders and Almaric of Cyprus. The commander of the Temple Peter of Moncada was killed, as well as Bartholomew Embriaco.[6] The population of the city was massacred, although many managed to escape by ship. Those who had taken refuge on the nearby island of Saint-Thomas were captured by the Mamluks on April 29. Women and children were taken as slaves, and 1200 prisoners were sent to Alexandria to work in the Sultan's new arsenal.

Tripoli was razed to the ground, and Qalawun ordered a new Tripoli to be built on another spot, a few miles inland at the foot of Mount Pilgrim. Soon other nearby cities were also captured, such as Nephin and Le Boutron. Peter of Gibelet kept his lands around Gibelet (modern Byblos) for about 10 more years, in exchange for the payment of a tribute to the Sultan.[7]

Aftermath

Two years later Acre, the last major Crusader outpost in the Holy Land was also captured in the Siege of Acre in 1291. It was considered by many historians to mark the end of the Crusades, though there were still a few other territories being held to the north, in Tortosa and Atlit. However the last of those, the small Templar garrison on the island of Ruad was captured in 1302 or 1303 in a siege. With the Fall of Ruad, was lost the last bit of Crusader-held land in the Levant.

Notes

References

- Tyerman, Christopher, God's war, A new history of the Crusades, ISBN 0-7139-9220-4

- Richard, Jean, Histoire des Croisades, ISBN 2-213-59787-1

- Runciman, Steven, A History of the Crusades, III, ISBN 0-14-013705-X