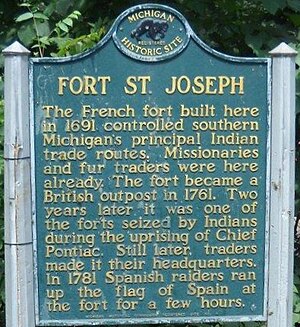

Fort St. Joseph (Niles, Michigan)

| Fort Saint Joseph | |

|---|---|

Fort Saint Joseph | |

| Niles, Michigan | |

Fort St. Joseph marker | |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1691 |

| Built by | French |

| In use | Fur Trade Post |

| Demolished | 1795 |

| Battles/wars | American Revolution |

| Events | Pontiac's Rebellion, Raid of 1780 and Raid of 1781 |

Fort St. Joseph Site (20BE23) | |

| Location | Niles, Michigan |

|---|---|

| NRHP reference No. | 73000944[1] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | May 24, 1973 |

| Designated MSHS | February 18, 1956[2] |

Fort Saint Joseph was a fort established on land granted to the Jesuits by King Louis XIV; it was located on what is now the south side of the present-day town of Niles, Michigan. Père Claude-Jean Allouez established the Mission de Saint-Joseph in the 1680s. Allouez ministered to the local Native Americans.

The French built the fort in 1691 mainly as a trading post on the lower Saint Joseph River. It was located where one branch of the Old Sauk Trail, a major east-west Native American trail, and the north-south Grand River Trail meet; together the combined trail fords the river. The fort was a significant stronghold of the fur trade at the southern end of Lake Michigan. Prior to the French and Indian War (also known as the Seven Years' War), the post had a French garrison of 10 soldiers, a commandant, blacksmith, Catholic priest, interpreter, and 15 additional households.[3]

With their victory in the war, the British took over the fort and maintained it for the fur trade. During the American Revolutionary War, they used it to supply their American Indian allies against the rebellious Continentals. The Spanish raided the fort in 1781 and briefly claimed it and the St. Joseph River as their territory. The British maintained the fort until after the United States victory in the Northwest Indian War and the signing of Jay's Treaty in 1795. After the British abandoned the fort, it fell into ruin and was overtaken by forest.

The fort site was not rediscovered until 1998. An archeology excavation has been underway since 2002. Among the rare artifacts discovered is an intact Jesuit religious medallion from the 1730s, one of only two found in North America. In December 2010, the team revealed a foundation wall and corner posts of one of the original buildings.

The site is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and is a state-registered site as well.

French and Indian War

During the Battle of Jumonville Glen, considered the first battle of the French and Indian War in North America, Joseph Coulon de Jumonville was killed. He was the son of Nicolas-Antoine Coulon de Villiers and the half-brother of Captain Louis Coulon de Villiers, who was stationed at Fort St. Joseph. Louis Coulon de Villiers vowed revenge for his brother's death.

After the British defeat of France in the Seven Years' War, France transferred the fort over to the British, who occupied it in October 1761.

Pontiac's Rebellion

On May 25, 1763, during Pontiac's Rebellion, the fort was captured by Potawatomi warriors. They killed most of the British 15-man garrison outright, and took the commander, Ensign Francis Schlosser, captive. They took him to Detroit to be ransomed as a prisoner, as was common for higher-ranking men.[4] After Pontiac's Rebellion, the British maintained the fort as a trading post, but did not garrison it again until 1779.[5]

American Revolution

Raid of 1780

During the war, the British used Fort St. Joseph to equip the Miami, Potawatomi, and other American Indians who were their allies in the war against the rebellious Continentals. In 1780 Americans from Cahokia, Illinois, led by Jean-Baptiste Hamelin and Lt. Thomas Brady, raided the fort. The British Lt. Dagreaux Du Quindre led forces after the raiding party; he overtook and defeated them near Petit Fort (in present-day Indiana).

Spanish Expedition of 1781

After the defeat of Hamelin's party, two Milwaukee chiefs, El Heturnò and Naquiguen, traveled to Spanish-held St. Louis; they arrived on 26 December 1780, to report the failed raid. They asked for assistance to raid the fort again. Don Francisco Cruzat, Commandant of St. Louis, dispatched the militia Captain Don Eugenio Pouré with 60 volunteers and Native allies. The force also included Ensign Charles Tayon and the interpreter Louis Chevalier.

The Spanish and Native force travelled via the Illinois River and Kankakee River to modern Dunns Bridge, Indiana, where it turned Northeast and marched towards Fort St. Joseph.[6] Before the Spanish and their allies attacked the fort, they promised the Potawatomi half the bounty if they would remain neutral.[7] Captain Pouré took Fort St. Joseph by surprise on 12 February 1781 by racing across the ice and taking the fort before the defenders could go to arms.[6]

He had the Spanish colors raised and claimed Fort St. Joseph and the St. Joseph River for Spain. His troops plundered the fort for one day, distributing the goods among natives before departing. Lt. Dagneau de Quindre arrived the next day, but was unable to persuade his native allies to pursue the raiders.[6] The Spanish arrived at St. Louis on 6 March without incident.[6] Pouré delivered the British flag to Cruzat.[8]

Some historians have described the attack as Spanish retaliation for the British attack on St. Louis in the previous year.[6] When Cruzat wrote about it to Governor Gálvez, he justified the raid as needing to appear strong to his Native allies, and to forestall British actions in the region.[9] Although Cruzat treated the raid as an act of Indian affairs, the looting and destruction of goods held at Fort St. Joseph also dissuaded a second British attack into Spanish territory.[10]

Jay's Treaty

The British finally abandoned the fort after the United States victory in the Northwest Indian War and the signing of Jay's Treaty in 1795. The fort gradually fell into ruin and was overgrown. Based on its Fort St. Joseph expedition, Spain claimed lands east of the Mississippi River, but this was not recognized by the United States. With the signing of Pinckney's Treaty (1795) with the US, Spain gave up any claim of land east of the Mississippi.[11] Because of the long dispute over the land, the diplomats Benjamin Franklin and John Jay considered the Spanish Fort St. Joseph campaign to have been little more than a ploy to claim the Northwest Territory. Franklin warned they want to "shut us up within the Appalachian Mountains."[11]

Rediscovery to present

Pothunters in the late 1800s recovered hundreds of artifacts from the fort site, which are now displayed in the Fort St. Joseph Museum in Niles. They include "trade silver, musket parts, glass beads, buttons, gunflints, knife blades, and door hinges."[4] The specific location of the 15-acre fort site was forgotten, and part of is likely underwater since a dam upriver raised the water level.[4]

The site was not rediscovered until an archeological survey in 1998.[12][13] Support the Fort, a local interest group founded in 1992, has helped sponsor a major archeological excavation on site, which began in 2002.

The team from Western Michigan University (WMU) has conducted a public archeology program as the project has developed, with a total of 10,000 visitors coming to the annual two-day field school. WMU's related activities have included workshops for graduate students and volunteers, three week-long training programs for middle school and high school teachers, and community outreach, including biweekly lectures at the library.[14] The seasonal excavations have uncovered rare artifacts, such as a 1730s Jesuit religious medallion, one of only two found in North America.[15] In December 2010 the team made a critical find of a foundation wall and two wooden posts of one of the buildings, helping establish its scale.[14]

Support the Fort has arranged related annual living history exhibits and re-enactments, featuring elements of Potowatomi, French, British and American life at the fort and in the region. In the future, they intend to construct a replica of the fort, with space to interpret the artifacts found through controlled excavation. This was the only fort in Michigan to be controlled by four different nations: France, Great Britain, Spain, and the United States.[12] It was always a multicultural site, a meeting and trading place for the ethnic Europeans with the Potowatomi, Ottawa and Ojibwe nations. It was sometimes the scene for formal marriages among the different ethnicities.[16]

References

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. 2009-03-13.

- ^ State of Michigan (2009). "Fort St. Joseph Site (20BE23)". Retrieved June 26, 2010.

- ^ Nassaney, 28

- ^ a b c Myers, Robert C. "Historic Sites: Fort St. Joseph". Northwest Territory Alliance. Retrieved 29 December 2010.

- ^ "About Fort St. Joseph. Fort History". Western Michigan University. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Collins, William. "The Spanish Attack On Fort St. Joseph". National Park Service. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- ^ Skaggs, 214

- ^ Skaggs, 208

- ^ Skaggs, 219

- ^ Paré, pg 47-48

- ^ a b Skaggs, 209

- ^ a b Lou Mumford, "Fort St. Joseph believed located", South Bend Tribune, November 6, 1998

- ^ "Transcript of press conference given by Dr. Michael Nassaney", November 5, 1998, Michigan Archaeological Society website

- ^ a b "Critical find at Fort St. Joseph", Archeology News Network, source Niles Daily Star, 5 December 2010, accessed 11 August 2011

- ^ Dr. Michael S. Nassaney, Dr. Jose Antonio Brandao, Dr. William M. Cremins, and Brock A. Giordano, et al., "Archeological Evidence of Economic Activities at an Eighteenth-Century Frontier Outpost in the Western Great Lakes", Historical Archeology, 2007. 41(4):3-19, reproduced in part at Support The Fort Website, accessed 11 August 2011

- ^ Nassaney, 29

Sources

- Myers, Robert C. "Historic Sites: Fort St. Joseph". Northwest Territory Alliance. Retrieved 29 December 2010.

- Nassaney, Michael (November 2009). "Fort St. Joseph. Archaeology and Public Outreach". Past Horizons: 27–30. Retrieved 29 December 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|journal=(help) - Nassaney, Dr. Michael S., Dr. Jose Antonio Brandao, Dr. William M. Cremins, and Brock A. Giordano, et al., "Archeological Evidence of Economic Activities at an Eighteenth-Century Frontier Outpost in the Western Great Lakes", Historical Archeology, 2007. 41(4):3-19, reproduced in part at Support The Fort Website

- Paré, George. "The St. Joseph Mission". Bloomington, Indiana: Glenn A. Black Laboratory of Archaeology, Indiana University. Retrieved 29 December 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Skaggs, David Curtis, ed. (1977). The Old Northwest in the American Revolution. Madison, Wisconsin: The State Historical Society of Wisconsin. ISBN 0-87020-164-6.

External links

- "Fort St. Joseph Archaeological Project", Official Website, Western Michigan University

- Fort St. Joseph Museum (City of Niles)

- SupportTheFort.net, dedicated to Fort St. Joseph research, reenactment, and education.

- Support the Fort! (Michigan Archaeological Society)

- Pre-1835 Chicago History

- Daniel McCoy, Old Fort St. Joseph; or, Michigan under four flags, Wynkoop Hallenbeck Crawford Co., 1907

- Colonial forts in Michigan

- French forts in the United States

- French-American culture in Michigan

- Forts in Michigan

- Michigan in the American Revolution

- Pontiac's War

- National Register of Historic Places in Michigan

- Michigan State Historic Sites

- Niles, Michigan

- Buildings and structures in Berrien County, Michigan

- Archaeological sites in Michigan

- Forts on the National Register of Historic Places in Michigan

- 1691 establishments in New France