Frequency analysis

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (March 2009) |

In cryptanalysis, frequency analysis is the study of the frequency of letters or groups of letters in a ciphertext. The method is used as an aid to breaking classical ciphers.

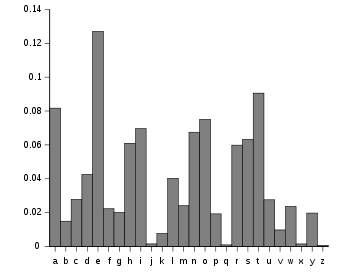

Frequency analysis is based on the fact that, in any given stretch of written language, certain letters and combinations of letters occur with varying frequencies. Moreover, there is a characteristic distribution of letters that is roughly the same for almost all samples of that language. For instance, given a section of English language, E, T, A and O are the most common, while Z, Q and X are rare. Likewise, TH, ER, ON, and AN are the most common pairs of letters (termed bigrams or digraphs), and SS, EE, TT, and FF are the most common repeats.[1] The nonsense phrase "ETAOIN SHRDLU" represents the 12 most frequent letters in typical English language text.

In some ciphers, such properties of the natural language plaintext are preserved in the ciphertext, and these patterns have the potential to be exploited in a ciphertext-only attack.

Frequency analysis for simple substitution ciphers

In a simple substitution cipher, each letter of the plaintext is replaced with another, and any particular letter in the plaintext will always be transformed into the same letter in the ciphertext. For instance, if all occurrences of the letter e turn into the letter X, a ciphertext message containing numerous instances of the letter X would suggest to a cryptanalyst that X represents e.

The basic use of frequency analysis is to first count the frequency of ciphertext letters and then associate guessed plaintext letters with them. More Xs in the ciphertext than anything else suggests that X corresponds to e in the plaintext, but this is not certain; t and a are also very common in English, so X might be either of them also. It is unlikely to be a plaintext z or q which are less common. Thus the cryptanalyst may need to try several combinations of mappings between ciphertext and plaintext letters.

More complex use of statistics can be conceived, such as considering counts of pairs of letters (bigrams), triplets (trigrams), and so on. This is done to provide more information to the cryptanalyst, for instance, Q and U nearly always occur together in that order in English, even though Q itself is rare.

An example

Suppose Eve has intercepted the cryptogram below, and it is known to be encrypted using a simple substitution cipher as follows:

LIVITCSWPIYVEWHEVSRIQMXLEYVEOIEWHRXEXIPFEMVEWHKVSTYLXZIXLIKIIXPIJVSZEYPERRGERIM WQLMGLMXQERIWGPSRIHMXQEREKIETXMJTPRGEVEKEITREWHEXXLEXXMZITWAWSQWXSWEXTVEPMRXRSJ GSTVRIEYVIEXCVMUIMWERGMIWXMJMGCSMWXSJOMIQXLIVIQIVIXQSVSTWHKPEGARCSXRWIEVSWIIBXV IZMXFSJXLIKEGAEWHEPSWYSWIWIEVXLISXLIVXLIRGEPIRQIVIIBGIIHMWYPFLEVHEWHYPSRRFQMXLE PPXLIECCIEVEWGISJKTVWMRLIHYSPHXLIQIMYLXSJXLIMWRIGXQEROIVFVIZEVAEKPIEWHXEAMWYEPP XLMWYRMWXSGSWRMHIVEXMSWMGSTPHLEVHPFKPEZINTCMXIVJSVLMRSCMWMSWVIRCIGXMWYMX

For this example, uppercase letters are used to denote ciphertext, lowercase letters are used to denote plaintext (or guesses at such), and X~t is used to express a guess that ciphertext letter X represents the plaintext letter t.

Eve could use frequency analysis to help solve the message along the following lines: counts of the letters in the cryptogram show that I is the most common single letter,[2] XL most common bigram, and XLI is the most common trigram. e is the most common letter in the English language, th is the most common bigram, and the the most common trigram. This strongly suggests that X~t, L~h and I~e. The second most common letter in the cryptogram is E; since the first and second most frequent letters in the English language, e and t are accounted for, Eve guesses that E~a, the third most frequent letter. Tentatively making these assumptions, the following partial decrypted message is obtained.

heVeTCSWPeYVaWHaVSReQMthaYVaOeaWHRtatePFaMVaWHKVSTYhtZetheKeetPeJVSZaYPaRRGaReM WQhMGhMtQaReWGPSReHMtQaRaKeaTtMJTPRGaVaKaeTRaWHatthattMZeTWAWSQWtSWatTVaPMRtRSJ GSTVReaYVeatCVMUeMWaRGMeWtMJMGCSMWtSJOMeQtheVeQeVetQSVSTWHKPaGARCStRWeaVSWeeBtV eZMtFSJtheKaGAaWHaPSWYSWeWeaVtheStheVtheRGaPeRQeVeeBGeeHMWYPFhaVHaWHYPSRRFQMtha PPtheaCCeaVaWGeSJKTVWMRheHYSPHtheQeMYhtSJtheMWReGtQaROeVFVeZaVAaKPeaWHtaAMWYaPP thMWYRMWtSGSWRMHeVatMSWMGSTPHhaVHPFKPaZeNTCMteVJSVhMRSCMWMSWVeRCeGtMWYMt

Using these initial guesses, Eve can spot patterns that confirm her choices, such as "that". Moreover, other patterns suggest further guesses. "Rtate" might be "state", which would mean R~s. Similarly "atthattMZe" could be guessed as "atthattime", yielding M~i and Z~m. Furthermore, "heVe" might be "here", giving V~r. Filling in these guesses, Eve gets:

hereTCSWPeYraWHarSseQithaYraOeaWHstatePFairaWHKrSTYhtmetheKeetPeJrSmaYPassGasei WQhiGhitQaseWGPSseHitQasaKeaTtiJTPsGaraKaeTsaWHatthattimeTWAWSQWtSWatTraPistsSJ GSTrseaYreatCriUeiWasGieWtiJiGCSiWtSJOieQthereQeretQSrSTWHKPaGAsCStsWearSWeeBtr emitFSJtheKaGAaWHaPSWYSWeWeartheStherthesGaPesQereeBGeeHiWYPFharHaWHYPSssFQitha PPtheaCCearaWGeSJKTrWisheHYSPHtheQeiYhtSJtheiWseGtQasOerFremarAaKPeaWHtaAiWYaPP thiWYsiWtSGSWsiHeratiSWiGSTPHharHPFKPameNTCiterJSrhisSCiWiSWresCeGtiWYit

In turn, these guesses suggest still others (for example, "remarA" could be "remark", implying A~k) and so on, and it is relatively straightforward to deduce the rest of the letters, eventually yielding the plaintext.

hereuponlegrandarosewithagraveandstatelyairandbroughtmethebeetlefromaglasscasei nwhichitwasencloseditwasabeautifulscarabaeusandatthattimeunknowntonaturalistsof courseagreatprizeinascientificpointofviewthereweretworoundblackspotsnearoneextr emityofthebackandalongoneneartheotherthescaleswereexceedinglyhardandglossywitha lltheappearanceofburnishedgoldtheweightoftheinsectwasveryremarkableandtakingall thingsintoconsiderationicouldhardlyblamejupiterforhisopinionrespectingit

At this point, it would be a good idea for Eve to insert spaces and punctuation:

Hereupon Legrand arose, with a grave and stately air, and brought me the beetle from a glass case in which it was enclosed. It was a beautiful scarabaeus, and, at that time, unknown to naturalists—of course a great prize in a scientific point of view. There were two round black spots near one extremity of the back, and a long one near the other. The scales were exceedingly hard and glossy, with all the appearance of burnished gold. The weight of the insect was very remarkable, and, taking all things into consideration, I could hardly blame Jupiter for his opinion respecting it.

In this example from The Gold-Bug, Eve's guesses were all correct. This would not always be the case, however; the variation in statistics for individual plaintexts can mean that initial guesses are incorrect. It may be necessary to backtrack incorrect guesses or to analyze the available statistics in much more depth than the somewhat simplified justifications given in the above example.

It is also possible that the plaintext does not exhibit the expected distribution of letter frequencies. Shorter messages are likely to show more variation. It is also possible to construct artificially skewed texts. For example, entire novels have been written that omit the letter "e" altogether — a form of literature known as a lipogram.

History and usage

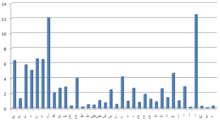

The first known recorded explanation of frequency analysis (indeed, of any kind of cryptanalysis) was given in the 9th century by Al-Kindi, an Arab polymath, in A Manuscript on Deciphering Cryptographic Messages.[3] It has been suggested that close textual study of the Qur'an first brought to light that Arabic has a characteristic letter frequency.[4] Its use spread, and similar systems were widely used in European states by the time of the Renaissance. By 1474, Cicco Simonetta had written a manual on deciphering encryptions of Latin and Italian text.[5] Arabic Letter Frequency and a detailed study of letter and word frequency analysis of the entire book of Qur'an are provided by Intellaren Articles.[6]

Several schemes were invented by cryptographers to defeat this weakness in simple substitution encryptions. These included:

- Homophonic substitution: Use of homophones — several alternatives to the most common letters in otherwise monoalphabetic substitution ciphers. For example, for English, both X and Y ciphertext might mean plaintext E.

- Polyalphabetic substitution, that is, the use of several alphabets — chosen in assorted, more or less devious, ways (Leone Alberti seems to have been the first to propose this); and

- Polygraphic substitution, schemes where pairs or triplets of plaintext letters are treated as units for substitution, rather than single letters, for example, the Playfair cipher invented by Charles Wheatstone in the mid-19th century.

A disadvantage of all these attempts to defeat frequency counting attacks is that it increases complication of both enciphering and deciphering, leading to mistakes. Famously, a British Foreign Secretary is said to have rejected the Playfair cipher because, even if school boys could cope successfully as Wheatstone and Playfair had shown, "our attachés could never learn it!".

The rotor machines of the first half of the 20th century (for example, the Enigma machine) were essentially immune to straightforward frequency analysis. However, other kinds of analysis ("attacks") successfully decoded messages from some of those machines.

Frequency analysis requires only a basic understanding of the statistics of the plaintext language and some problem solving skills, and, if performed by hand, tolerance for extensive letter bookkeeping. During World War II (WWII), both the British and the Americans recruited codebreakers by placing crossword puzzles in major newspapers and running contests for who could solve them the fastest. Several of the ciphers used by the Axis powers were breakable using frequency analysis, for example, some of the consular ciphers used by the Japanese. Mechanical methods of letter counting and statistical analysis (generally IBM card type machinery) were first used in World War II, possibly by the US Army's SIS. Today, the hard work of letter counting and analysis has been replaced by computer software, which can carry out such analysis in seconds. With modern computing power, classical ciphers are unlikely to provide any real protection for confidential data.

Frequency analysis in fiction

Frequency analysis has been described in fiction. Edgar Allan Poe's "The Gold-Bug", and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes tale "The Adventure of the Dancing Men" are examples of stories which describe the use of frequency analysis to attack simple substitution ciphers. The cipher in the Poe story is encrusted with several deception measures, but this is more a literary device than anything significant cryptographically.

See also

- ETAOIN SHRDLU

- Letter frequencies

- Arabic Letter Frequency

- Index of coincidence

- Topics in cryptography

- Zipf's law

- A Void, a novel by Georges Perec. The original French text is written without the letter e, as is the English translation. The Spanish version contains no a.

Further reading

- Helen Fouché Gaines, "Cryptanalysis", 1939, Dover. ISBN 0-486-20097-3

- Abraham Sinkov, "Elementary Cryptanalysis: A Mathematical Approach", The Mathematical Association of America, 1966. ISBN 0-88385-622-0.

References

- ^ Singh, Simon. "The Black Chamber: Hints and Tips". Retrieved 26 October 2010.

- ^ A worked example of the method from bill's "A security site.com"

- ^ Ibrahim A. Al-Kadi "The origins of cryptology: The Arab contributions", Cryptologia, 16(2) (April 1992) pp. 97–126.

- ^ "In Our Time: Cryptography". BBC Radio 4. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- ^ Kahn, David L. (1996). The codebreakers: the story of secret writing. New York: Scribner. ISBN 0-684-83130-9.

- ^ Madi, Mohsen M. (2010). "Quran Suras Statistics". Intellaren Articles. Retrieved 16 January 2011.

External links

- Free tools to analyse texts: Frequency Analysis Tool (with source code)

- Tools to analyze Arabic text

- Statistical Distributions of Arabic Text Letters

- Statistical Distributions of English Text

- Statistical Distributions of Czech Text

- Free Online Character Frequency Analyzer

- Character and Syllable frequencies of 33 languages and a portable tool to create frequency and syllable distributions

- English Frequency Analysis based on a live data stream of posts from a forum.

- Decrypting Text