Friedrich Eckenfelder

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Friedrich Eckenfelder | |

|---|---|

Self-portrait around 1924 | |

| Born | 6 March 1861 Bern |

| Died | 11 May 1938 (aged 77) Balingen |

| Nationality | German |

| Education | Academy of Fine Arts, Munich |

| Known for | Drawing, painting |

| Notable work | Pflügende Pferde |

| Movement | Impressionism |

| Elected | Munich Secession |

Friedrich Eckenfelder (6 March 1861 – 11 May 1938) was a Swiss-German impressionist painter, best known for his portrayals of farm horses and for townscapes with a background of the Swabian Alps. He was born and raised in modest circumstances, but his talent was discovered at an early age, so that he was able to receive training as a painter and later to enroll in the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich. There he became one of the founding members of the Munich Secession.

Eckenfelder's preferred choice of subject emerged early on. By 1878, at the end of his basic education, he was referred to in a document as an "animal painter". After the First World War and the resulting changes in society and art, Eckenfelder moved back to Swabia. He was named an honorary citizen of Balingen in 1928, a street was named for him in 1931, a gallery devoted to his work was established in the town museum in 1978, and the banqueting hall of the town community centre was named in his honour.

Biography

Youth

pencil sketch by Eckenfelder in 1884

Friedrich Eckenfelder was born in Bern, the second child of the housekeeper Rosina Vivian and the shoemaker Johann Friedrich Eckenfelder, who had moved from Balingen to Basel when he was appointed journeyman shoemaker in 1859 and there met his future wife.[citation needed] They moved together to Bern while still unmarried, then when Rosina was again pregnant in 1865,[citation needed] the family moved to Balingen and they were married there on 18 July 1865.[clarification needed] The children were declared legitimate through marriage and declared citicens of Württemberg through their mother.[clarification needed] The boy's talent for drawing was discovered in elementary school and advanced training was recommended, which he received from 1875 in Professor Oskar Hölder's drawing class in Rottweil.[citation needed]

The fourteen-year-old boy was raised in Rottweil at his teacher's home as well as with the family of a senior forestry official named Junginger, one of Hölder's friends. There he met Marie Junginger, fourteen years his senior, who was working as a portrait painter after training with Hölder. Eckenfelder and Junginger went to Munich together in 1878, and Eckenfelder began his studies at the Academy of Fine Arts in October.[citation needed] In late December 1878, Maria became pregnant. She gave birth to their son Friedrich Junginger on 19 September 1879 in Munich. Eckenfelder's family tried to conceal this "misstep", from the age of six months, the boy was raised by his grandparents, as if he were their own child.[citation needed] The younger Friedrich was deeply affected when he was eventually told that the man he had had a brotherly relationship with was in fact his father.[1]

In Munich

Marie Junginger and Friedrich Eckenfelder lived in close proximity in Munich, sometimes together. Eckenfelder's biographer Walter Schnerring notes an increasing alienation.[citation needed] In 1899, their son received a position as a bookseller in Stuttgart, Marie Junginger moved to be with him, with her now widowed mother.[who?] From 1904 on, when Marie moved away, the contact between Eckenfelder and her was severed. However, she remained in contact with her son, who later opened a bookshop in Arosa, until his death in 1927.[2][clarification needed]

Eckenfelder lived in the artists' quarter of Munich, Maxvorstadt, sharing quarters with Bernhard Buttersack. Christian Landenberger lived on the opposite side of the staircase. Paul Burmester, Georg Jauss, Richard Winternitz and Gino von Finetti moved in the same circle, as well as the "Schwabenburg" (Swabian castle) and the atelier of the painters Anton Braith and Christian Mali. Their meeting place was the "Arzberger Keller" (Arzbergian basement).[3][dubious – discuss]

Notable teachers at the Munich Academy of Fine Arts at the time were Carl Theodor von Piloty, Wilhelm von Diez, Ludwig von Löfftz and Wilhelm von Lindenschmit the Younger. In addition, Eckenfelder was the first private pupil of Heinrich von Zügel.[citation needed] The latter was also a pupil of Hölder; their relationship was a "... mixture of teacher/pupil, friendship and father/son relationship."[3] Eckenfelder also had contact with his family on excursions to the Dachau Marsh for painting En plein air or on autumn visits to Zügel's home town of Murrhardt. Eckenfelder was not part of the class when Zügel began his academy career. The intensive teacher–pupil relationship existed only in private gatherings and meetings. Zügel took an interest in Eckenfelder's economic situation. He tried to provide Eckenfelder with a professorship at the academy, but failed because of the latter's introversion.[4] Both artists were members of the artists' society Allotria and in 1892 founding members of the Munich Secession. Eckenfelder showed two horse paintings at the founding exhibition in 1888, and at the exhibitions in 1896, 1899, 1903, 1906 and 1911.[5]

Already in 1883, Eckenfelder had exhibited his Überschwemmung im Neckarthal (Flooding in the Neckar Valley) at the international art exhibition in the Glaspalast in Munich. Prince Regent Luitpold of Bavaria purchased his painting Pferde vor dem Pflug (Ploughing Horses) in 1888 and Eckenfelder was for the first time mentioned in the specialist press.[citation needed] The prince regent took a lively interest in the artistic life of Munich and through such acquisitions supported young artists not only financially, but also with the renown they entailed.[clarification needed] He often visited painters in their studios. When he paid his first such visit to Eckenfelder, it was a cold day and the artist was wrapped up against the cold and wearing thick winter slippers; Eckenfelder was so embarrassed that soon after he formed the habit of wearing dress shoes and a suit with no smock when working. He maintained this habit until late in life.[6]

Eckenfelder earned the Gold Medal, Second Class, in 1909 for Schimmel in der Schwemme (Greys in the Pond). One critic remarked: "Friedrich Eckenfelder's Greys in the Pond prove that not everything needs to be painted in adherence with the Zügel school to have effect and power."[7] In 1913, he showed Pferdemarkt (Horse Market) at the international exhibition in the Glaspalast. He also participated in exhibitions in Berlin, Frankfurt, Wiesbaden and Stuttgart. Buyouts by the King of Württemberg further increased his market value. His pictures suited the contemporary taste and sold well, partly through Munich dealers, but also through Goldschmid in Frankfurt, Hermes in Wiesbaden, Schaller und Fleischhauer in Stuttgart and dealers in Mainz, Düsseldorf and Berlin. Sometimes he sold his paintings for cash, directly off the easel.[8]

In the 1890s, as more and more of his fellow artists were moving away from Munich, Eckenfelder decided to spend summers in Balingen and in the Swabian Alps. Sketches and paintings were then transported to Munich in the autumn to be presented to friends, colleagues and customers. This was the period of his greatest artistic independence.[8]

Homeland paintings in Balingen

View up Friedrichstrasse in Balingen

In contrast, his biographer, Schnerring, describes Eckenfelder's eventual final move to Balingen in 1922 as a withdrawal.[9] The collapse of the monarchy and his friend Zügel's dismissal from his post as director of the Academy by the Bavarian Soviet Republic badly affected Eckenfelder, who was now in his sixties and in poor health. He did not further participate in the "New Secession" or the "Blue Rider". He entered a comfortable retirement in Balingen, looked after by his sister Rosine Wagner. He enjoyed a good reputation in the town; owning one of his paintings was a status symbol for the established families:

The horse picture in the best room was seen as an artistic representation of one's own roots in the Swabian Alps and one's own character as a profound kind of person who consistently ploughs a straight line through life, as the simple denizen of the Swabian Alps might think of himself, but could never have expressed like this painter.[10]

He had his local patrons and was known to all, since he could be found painting in distinctive places, always wearing a suit.[citation needed] From 5 to 15 July 1924, a retrospective of his work was held in the then new gymnasium of the Sichelschule.[citation needed] He was named an honorary citizen of the town in 1928;[citation needed] he presented the town with a self-portrait, and they bought two panoramas of the town with backgrounds of the Swabian Alps, in one case between Hohenzollern Castle and the Schalksburg and in the other between Lochenhörnle and the Plettenberg. All three pictures are preserved in the Eckenfelderzimmer (Eckenfelder Room) in the town hall, which is now used for weddings.[11] A street was named in his honour in 1931, for his 70th birthday. To express his gratitude, Eckenfelder offered the town their choice of twelve pictures at bargain prices. Making their selection, they noted that "the earlier pictures are significantly more valuable than the ones from the present".[12]

The Nazis respected Eckenfelder's work, whose motifs could easily be interpreted in terms of their blood and soil ideology.[citation needed] On 9 December 1928 Eckenfelder had signed a joint election manifesto issued by the Sparerbund (Association of Savers) and the Nazi Party, although he was not a member of either organization.[citation needed] In Württemberg at that time, the Nazis had a stronger conservative orientation and entered into coalitions on the local level with single-issue middle-class parties. Friedrich Eckenfelder, whose monarchist worldview had been badly shaken by the Munich Soviet Republic and who was affected by the hyperinflation of the period, could certainly identify with the contents of the manifesto.[citation needed] As a figurehead, he headed the joint Nazi-Sparerbund candidate list, but evidently the voters did not take his candidacy seriously: he received markedly fewer votes than candidates further down the list.[13] In 1933, as Balingen's most prominent contemporary artist, he was commissioned by the town to produce paintings as gifts for the three newest honorary citizens: Hitler, Hindenburg and Murr. The local Nazi Party headquarters commissioned him to paint a portrait of Hitler.[14]

When Eckenfelder returned to Balingen, he met Elsa Martz. 18 years his junior, she was an alto singer and piano teacher from a prosperous middle-class family. When she was young, she had enjoyed going to the opera; however, her family regarded this as beneath their station. Despite or because of receiving many marriage proposals, she had remained single. She and Eckenfelder developed a platonic love. They wrote each other love letters using the formal mode of address, Sie, visited each other, went on walks together and exchanged gifts. He gave her a self-portrait and a landscape, Steinach mit Endingen und Plettenberg, and she referred to the picture as Bächlein meiner Liebe (Little brook of my love).[15] Many people in Balingen—even Eckenfelder's relatives—turned a blind eye to the relationship because they found it embarrassing.[citation needed] Martz did not attend Eckenfelder's funeral.[16]

Friedrich Eckenfelder died of pneumonia on 11 May 1938, after a three-week-long hospitalization. He was buried on the south side of the Balingen cemetery church. The atelier apartment in his parental home was made into a small museum with his pictures that had been donated to the town. Initially maintained by his nieces, the building was later inherited by the city. After it was demolished, the pictures were moved to the late medieval Zollernschloss Balingen. Today they are located in the "Friedrich Eckenfelder Galerie" in the former tithe barn, which has been converted into a museum.[17]

Work

The following list of works, and the descriptions, are derived from Walter Schnerring's monograph on Eckenfelder, which was written in association with a traveling exhibition of the artist's work on the occasion of the 125th anniversary of his birth.[18]

Education and 1880s

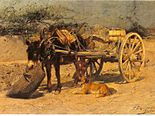

The following pictures show the influence of his teachers Löffitz and Diez. In the tradition of genre painting, the humans receive the same amount of attention as the animals: They rejoice in homecoming, toil at feeding time, or rest along with their horses. Eckenfelder also demonstrated an interest in human subjects at this time by producing several portraits. The motifs show the influence of other artists, such as a donkey pulling a cart (Braith) and flocks of sheep (Zügel).

Works of this period include the types that are icons of his later paintings: horses in harness at rest, riding out or riding home, and the Zollernschloss. Schnerring characterises his style as still searching, erratic and experimenting, but regards some of the paintings made during this phase as amongst his most successful.

-

Lustige Fahrt (Joyful Journeying), 1886/87

-

Bauer füttert seine Pferde (Farmer Feeding his Horses), 1886

-

Mittagsrast vor der Hütte (Midday Rest Outside the Hut), 1888

-

Bildnis eines alten Mannes (Portrait of an Old Man), around 1884

-

Maulesel am Karren (Mule and Cart), 1887

-

Schafe im Pferch (Sheep in the Fold), 1887

-

Zollernschloss, around 1884/85

-

Balingen mit Heuberg (Balingen with the Heuberg), 1893

1890s

In this period, the methods of impressionistic are increasingly evident, particularly in the treatment of light: warm, direct light, for example direct sunlight with its red tones, and partially cold light in shadows, with blue tints, and violet transitional zones. Eckenfelder's ploughing horses become more monumental and infused with pathos, but by means of the use of light they remain a part of the landscape.

Very common in this period are small-scale, often seemingly unfinished landscapes and landscape studies in the style of the Paysage intime, a forerunner genre of impressionism. The effect is to infuse nature with Romanticism. Eckenfelder regarded every kind of technology with suspicion. He never rode in a car or owned a camera.[19] During this period, Eckenfelder is described by the specialist press not only as an animal painter, but also as a landscape painter and "Kleinmeister" (a reference to the "Schweizer Kleinmeister" or Swiss Small Masters, a group of landscape painters who preserved their pictures in sketchbooks). In this period he also created a relatively large number of portraits of Balingen citizens.

-

Eichenwald im Vorfrühling (Oak Wood in Early Spring), 1894

-

Heimkehr vom Heuen (Return from Haying), around 1895

-

Bildstock am Baum (Tree with Shrine), 1890

-

Bildnis Frieda Jetter (Portrait of Frieda Jetter), 1898

Turn of the century to 1918

The larger formats and "great gestures" are not transferable to the artist's natural introverted mode of work. Schnerring wishes he had had the self-awareness of Carl Spitzweg, to know to retain the small format in his work.[20] The core motifs in this period are ploughing horses, portraits after photographs, riding home, and townscapes. The depiction of water in paintings of watering places and fords also emerges as a theme. However, the animals now have a shiny and cleaned up appearance and hardly show any traces of the weariness of hard-working beasts as they did in his earlier works. Humans now retreat into the background, but still serve as supernumeries whom the horses permit to hold their reins.[20]

In earlier pictures with a rear view of horses, Eckenfelder still succeeded in drawing the observer into the picture, similar to Caspar David Friedrich. In this period, the view is more confrontational. Eckenfelder was at that time a renowned artist in Munich with some important contributions to Munich Impressionism. With the end of the World War and of the monarchy, a deep rift occurred in his life. Up until then he had made his own statements; afterwards, he retreated increasingly into himself.[21]

-

Heimkehr am Abend (Return at Evening), 1899/1900

-

Zwei Schimmel in der Schwemme (Two Greys in the Pond), 1909

-

Schimmelgespann mit lustiger Bauerngesellschaft im Wagen (Greys Pulling a Cart with Happy Country People), around 1920

-

Vesperpause beim Pflügen (Evening Pause While Ploughing), before 1900

Later works

In this period, he mainly painted on commission: Portraits of citizens of Balingen, views of the town, flocks of sheep and horses: horses at the blacksmith's, pulling hay wagons, pulling post wagons, pulling coaches, etc. Eckenfelder complained about the bad quality of oil paints after the First World War; in particular, the yellow for warm summer light on the hide of a grey was no longer adequate for his requirements.

In his late works, weaknesses of composition emerge. The motif is ill-positioned, waysides crop corners, streets and clods of earth are poorly executed, so that the animals with their firm lines stick out of the picture.

-

Schafherde vor dem Hundsrücken (Flock of Sheep in Front of the Hundsröcken), around 1920

-

Balingen mit Bebelt, von Norden (Balingen with Bebelt, from the North), 1922

Eckenfelder's main themes

Townscapes of Balingen

There are about 30 full views of Balingen, plus in addition pictures of market scenes, individual houses—these clearly recognisable as commissions—and the ensemble on the waterfront of the Eyach with the Zollernschloss, water tower and weir. In addition, the mountains above Balingen form the background of many of the horse pictures. Many of the foreground locations in which Eckenfelder's horses are seen ploughing, were enclosed and made into housing estates after the Second World War.

-

Zollernschloss in Balingen, before 1895

-

Balingen von Westen (Balingen from the West), 1900

-

Zwei Gespanne vor dem "Hirsch" (Two Teams in Front of the "Hirsch" Inn), 1922

The old town of Balingen—Eckenfelder's Balingen—has a mountain panorama on three sides. The Heuberg rises behind the town, only 70–80 metres high, but at a distance of less than 500 metres, an imposing presence. Fewer than 5 km away, the Swabian Alps rise 350–480 metres to the east and south. The panorama on the east side extends from the Hohenzollern (855 m) to the Schalksburg. To the south, the so-called Balinger Berge (Balingen mountains), prominently split by the valley of the Eyach, include the Lochen and Lochenhörnle (956 m), the Lochenstein (963 m), the Schafberg (1,000 m), and the Plettenberg (1,002 m). These views can only be captured in pictures by compressing the horizontal and exaggerating the vertical; artistically, the challenge is to do this while keeping the mountains recognisable. In some late works, Eckenfelder no longer succeeded in this. The panorama from the Zollern to the Plettenberg comprises 170°. Eckenfelder never dared to portray this scene. He exceeded 200 centimetres (6.6 ft) in width only in two landscapes, both of which hang today in the wedding room of the Balingen town hall.

Ploughing horses

Landscapes, animal studies and portraits were individually depicted by Eckenfelder. After developing a compositional technique in which the object is aligned with the diagonal, he achieved an optimal depiction of a team of horses. The distance between human/plough and horses is naturally foreshortened and the rear horse in a pair can also be fully incorporated.[22]

-

Zwei Pferde am Pflug (Two Horses Ploughing), around 1886/89

-

Zwei pflügende Schimmel (Two Greys Ploughing), 1899/1900

-

Zwei Schimmel an der Egge (Two Greys Pulling a Harrow), around 1900

-

Zwei pflügende Braune bei Dachau (Two Chestnuts Ploughing at Dachau), 1908

In his late work, the motif of "ploughing horses with Balingen landscape background" emerges. Eckenfelder created well over a hundred variations on this theme. In his catalogue of the artist's works, Schnerring abandons purely chronological listing for this category in order to distinguish the paintings from each other. He classifies them by three criteria:[23]

- Number and colour of horses

- Direction of movement

- Background landscape

It is these "ploughing horses" for which Eckenfelder is best known. The quality of the portrayal declines beginning in 1922: "The teams of horses, initially integrated in colouring and composition, now gradually obstruct the landscape. Only in the final years do they once again become smaller; however, the painter no longer succeeds in melding them into a unity with their surroundings."[22]

See also

References

- ^ Schnerring, p. 18

- ^ Schnerring, p. 26

- ^ a b Schnerring, p. 73

- ^ Schnerring, p. 75

- ^ Schnerring, p. 78

- ^ Schnerring, p. 77

- ^ Schnerring, p. 79

- ^ a b Schnerring, pp. 80-83

- ^ Schnerring, pp. 83 and 119 et seq.

- ^ Schnerring, p. 120: "Im Pferdebild in der guten Stube sah man die eigene Einbettung in die Albheimat und den eigenen Charakter eines tief, geradlinig und stetig durch das Leben pflügenden Menschentyps in zeitloser Weise verdichtet, wie man es als einfacher Älbler zwar ahnte, aber nicht hätte so ausdrücken können wie dieser Maler."

- ^ Schnerring, p. 125.

- ^ Schnerring, p. 131: "[dass] die Bilder aus früherer Zeit bedeutend wertvoller sind als die der Jetztzeit".

- ^ Schnerring, pp. 130, 289

- ^ Schnerring, p. 130 et seq.

- ^ Der Neugierige on Wikisource

- ^ Schnerring, p. 129.

- ^ Schnerring, p. 132.

- ^ Schnerring, pp. 155 et seq.

- ^ Schnerring, p. 121.

- ^ a b Schnerring, p. 190.

- ^ Schnerring, p. 191.

- ^ a b Schnerring, p. 217

- ^ Schnerring, p. 218

Sources

- Walter Schnerring (1984). Der Maler Friedrich Eckenfelder. Ein Münchner Impressionist malt seine schwäbische Heimat (in German). Stuttgart: Konrad Theiss Verlag. ISBN 3-8062-0337-7.

External links

- Literature by and about Friedrich Eckenfelder in the German National Library catalogue