George Rogers Clark: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Infobox Military Person |

{{Infobox Military Person |

||

| name =george rogers |

| name =george rogers |

||

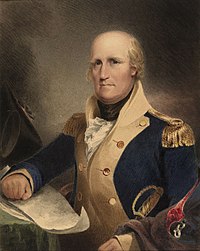

| image =[[File:George Rogers Clark.jpg|200px]] |

| image =[[File:George Rogers Clark.jpg|200px]] |

||

| caption = |

| caption = ford burgers |

||

| born = {{birth-date|November 19, 1752}} |

| born = {{birth-date|November 19, 1752}} |

||

| died = {{death-date|February 13, 1818 }} |

| died = {{death-date|February 13, 1818 }} |

||

Revision as of 19:13, 19 August 2009

george rogers | |

|---|---|

ford burgers | |

| Nickname(s) | Conqueror of the Old Northwest |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Service/ | Virginia Militia |

| Years of service | 1776–1790 |

| Rank | Lieutenant Colonel |

| Commands | Western Frontier |

| Battles/wars | American Revolutionary War Northwest Indian War |

| Spouse(s) | None |

| Children | None |

| Signature |  |

George Rogers Clark (November 19, 1752 – February 13, 1818) was a soldier from Virginia and the highest ranking American military officer on the northwestern frontier during the American Revolutionary War. He served as leader of the Kentucky militia throughout much of the war, Clark is best-known for his celebrated capture of Kaskaskia (1778) and Vincennes (1779), which greatly weakened British influence in the Northwest Territory. Because the British ceded the entire Northwest Territory to the United States in the 1783 Treaty of Paris, Clark has often been hailed as the "Conqueror of the Old Northwest."

Clark's military achievements all came before his 30th birthday. Afterwards he led militia in the opening engagements of the Northwest Indian War, but was accused of being drunken on duty. Despite his demand for a formal investigation into the accusations, he was disgraced and forced to resign causing him to leave Kentucky to live on the Indiana frontier. Never fully reimbursed by Virginia for his wartime expenditures, he spent the final decades of his life evading creditors, living in increasing poverty and obscurity. He was also involved in two failed conspiracies to open the Spanish controlled Mississippi River to American traffic. After suffering a stroke and losing his leg, he was aided in his final years by family members, including his younger brother William, one of the leaders of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Clark died of a stroke on February 13, 1818.

Early years

George Rogers Clark was born on November 19, 1752 in Albemarle County, Virginia, not far from the home of Thomas Jefferson.[1] He was the second of ten children of John Clark and Ann Rogers Clark, who were Anglicans of English and Scottish ancestry.[2] Five of their six sons became officers during the American Revolutionary War. Their youngest son, William Clark, was too young to fight in the Revolution, but later became famous as a leader of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. In about 1756, after the outbreak of the French and Indian War, the family moved away from the frontier to Caroline County, Virginia, and lived on a four-hundred acre plantation that later grew to over two-thousand.[3]

Little is known of Clark's schooling, but he went to live with his grandfather so he could attend Donald Robertson's school with James Madison and John Taylor of Caroline and received a common education.[4] He was also tutored at home, as was usual for Virginian children of the period, eventually becoming a farmer and being taught to survey land by his father.

At age nineteen, Clark left his home on his first surveying trip into western Virginia.[5] In 1772, as a twenty-year-old surveyor, Clark made his first trip into Kentucky via the Ohio River at Pittsburgh,[6] one of thousands of settlers entering the area as a result of the Treaty of Fort Stanwix of 1768.[7] In 1774, Clark was preparing to lead an expedition of ninety men down the Ohio River when war broke out with the American Indians. The tribes living in the Ohio country had not been party to the treaty signed with the Cherokee, which ceded the Kentucky hunting grounds to Britain for settlement. The violence that resulted eventually culminated in Lord Dunmore's War, in which Clark played a small role as a captain in the Virginia militia.[8]

Revolutionary War

As the American Revolutionary War began in the East, settlers in Kentucky were involved in a dispute over the region's sovereignty. Richard Henderson, a judge and land speculator from North Carolina, had purchased much of Kentucky from the Cherokees in an illegal treaty. Henderson intended to create a proprietary colony known as Transylvania, but many Kentucky settlers did not recognize Transylvania's authority over them. In June 1776, these settlers selected Clark and John Gabriel Jones to deliver a petition to the Virginia General Assembly, asking Virginia to formally extend its boundaries to include Kentucky.[9] Clark and Jones traveled via the Wilderness Road to Williamsburg, where they convinced Governor Patrick Henry to create Kentucky County, Virginia. Clark was given 500 lb (230 kg) of gunpowder to help defend the settlements and was appointed a major in the Kentucky County militia.[10] Clark was just twenty-four years old, but older settlers like Daniel Boone, Benjamin Logan, and Leonard Helm looked to him for leadership.

Illinois campaign

In 1777, the American Revolutionary War intensified in Kentucky. Native Americans, armed and encouraged by British lieutenant governor Henry Hamilton at Fort Detroit, waged war and raided the Kentucky settlers in hopes of reclaiming the region as their hunting ground. The Continental Army could spare no men for an invasion of the Northwest or the defense of distant Kentucky. Defense was left entirely to the local men.[11] Clark participated in several skirmishes against the Native American raiders. As a leader of the defense of Kentucky, Clark believed that the best way to end these raids was to seize British outposts north of the Ohio River, thereby destroying British influence with the Indians.[12] Clark asked Governor Henry for permission to lead a secret expedition to capture the nearest British posts, which were located in the Illinois country. Governor Henry commissioned Clark as a lieutenant colonel in the Virginia militia and authorized him to raise troops for the expedition.[13]

In July 1778, Clark and about 175 men crossed the Ohio River at Fort Massac and marched to Kaskaskia, taking it on the night of July 4.[14] Cahokia, Vincennes, and several other villages and forts in British territory were subsequently captured without firing a shot, because most of the French-speaking and American Indian inhabitants were unwilling to take up arms on behalf of the British. To counter Clark's advance, Henry Hamilton reoccupied Vincennes with a small force.[15] In February 1779, Clark returned to Vincennes in a surprise winter expedition and retook the town, capturing Hamilton in the process. The winter expedition was Clark's most significant military achievement and became the source of his reputation as an early American military hero.[16] When news of his victory reached General George Washington, his victory was celebrated and was used to encourage the alliance with France. Washington considered his victory a great success, especially considering he had received nearly no support from the regular army in men or funds.[17] Virginia also capitalized on Clark's success and laid claim to the whole of the Northwest by establishing the region as Illinois County, Virginia.[18]

Final years of the war

Clark's ultimate goal during the Revolutionary War was to seize British-held Detroit, but he could never recruit enough men to make the attempt. The Kentucky militiamen generally preferred to defend their homes by staying closer to Kentucky rather than making a long and potentially perilous expedition to Detroit. In June 1780, a mixed force of British and Indians from Detroit invaded Kentucky, capturing two fortified settlements and carrying away scores of prisoners. In August 1780, Clark led a retaliatory force that won a victory near the Shawnee village of Pekowee.[19] The next year Clark was promoted to brigadier general by Governor Thomas Jefferson, and was given command of all the militia in the Kentucky and Illinois counties. He prepared once more to lead an expedition against Detroit and Washington transferred a small group of regulars to assist Clark, but the detachment was disastrously defeated in August 1781 before they could meet up with Clark, ending the campaign.[20][21]

An even more extensive defeat was to follow the next year: in August 1782, another British-Indian force defeated the Kentucky militia at the Battle of Blue Licks. Although he had not been present at the battle, Clark, as senior military officer, was severely criticized in the Virginia Council for the disaster.[22] In response, Clark led another expedition into the Ohio country, destroying several Indian towns along the Great Miami River in the last major expedition of the war.[23]

The importance of Clark's activities in the Revolutionary War has been the subject of much debate. As early as 1779 he was called the Conqueror of the Northwest by George Mason.[24] Because the British ceded the entire Northwest Territory to the United States in the 1783 Treaty of Paris, some historians, including William Hayden English, credit Clark with nearly doubling the size of the original Thirteen Colonies by seizing control of the Illinois country during the war. Clark's Illinois campaign—particularly the surprise march to Vincennes—was greatly celebrated and romanticized.[17] Other historians, such as Lowell Harrison, have downplayed the importance of the campaign in the peace negotiations and the outcome of the war, arguing that Clark's "conquest" was little more than a temporary occupation.[25][26]

Later years

Clark was just thirty years old when the Revolutionary War ended, but his greatest military achievements were already behind him. Ever since Clark's victories in Illinois, settlers had been pouring into Kentucky, often illegally squatting on Indian land north of the Ohio River. From 1784 until 1788 Clark served as the superintendent-surveyor for Virginia's war veterans and surveyed the lands granted to them for their service in the war. The position brought a small income, but Clark devoted very little time to the enterprise.[27] Clark helped to negotiate the Treaty of Fort McIntosh in 1785[28] and the Treaty of Fort Finney in 1786 with tribes north of the river, but violence between Native Americans and Kentucky settlers continued to escalate.[29]

According to a 1790 U.S. government report, 1,500 Kentucky settlers had been killed in Indian raids since the end of the Revolutionary War.[30] In an attempt to end these raids, Clark led an expedition of 1,200 drafted men against Indians towns on the Wabash River in 1786, one of the first actions of the Northwest Indian War.[31] The campaign ended without a victory: lacking supplies, about three-hundred militiamen mutinied, and Clark had to withdraw, but not before concluding a ceasefire with the Indians. It was rumored, most notably by James Wilkinson, that Clark had often been drunk on duty.[32] Many years later, Wilkinson was found to be working as an secret agent of the Spanish Government. When Clark learned of the rumors he demanded an official inquiry be made, but his request was declined by Governor of Virginia, and Virginia Council condemned Clark's actions. Clark's reputation was tarnished, he never again led men in battle and left Kentucky, moving into the Indiana frontier near Clarksville[32][33]

Life in Indiana

Clark lived most of the rest of his life in financial difficulties. Clark had financed the majority of his military campaigns with borrowed funds. When creditors began to come to him for these unpaid debts, he was unable to obtain recompense from Virginia or the United States Congress because record keeping on the frontier during the war had been haphazard. For his services in the war Virginia gave Clark a gift of 150,000 acres (610 km2) of land. The soldiers who fought with Clark also received smaller tracts of land. Together with Clark's Grant and his other holdings, his ownership encompassed all of present day Clark County, Indiana and most of the surrounding counties.[34] Although Clark had claims to tens of thousands of acres of land resulting from his military service and land speculation, he was "land-poor", i.e. he owned much land but lacked the means to make money from it.

With his career seemingly over and his prospects for prosperity doubtful, on February 2, 1793, Clark offered his services to Edmond-Charles Genêt, the controversial ambassador of revolutionary France, hoping to earn money to maintain his estate.[35] Western Americans were outraged that the Spanish, who controlled Louisiana, denied Americans free access to the Mississippi River, their only easy outlet for long distance commerce. The Washington Administration was also seemingly deaf to western concerns about opening the Mississippi to U.S. commerce. Clark proposed to Genêt that, with French financial support, he could lead an expedition to drive the Spanish out of the Mississippi Valley. Genêt appointed Clark "Major General in the Armies of France and Commander-in-chief of the French Revolutionary Legion on the Mississippi River."[36] Clark began to organize a campaign to seize New Madrid, St. Louis, Natchez, and New Orleans, getting assistance from old comrades such as Benjamin Logan and John Montgomery, and winning the tacit support of Kentucky governor Isaac Shelby.[37] Clark spent $4,680 ($59,161 in 2009 chained dollars) of his own money for supplies.[38] In early 1794, however, President Washington issued a proclamation forbidding Americans from violating U.S. neutrality and threatened to dispatch General Anthony Wayne to Fort Massac to stop the expedition. The French government recalled Genêt and revoked the commissions he granted to the Americans for the war against Spain. Clark's planned campaign gradually collapsed, and he was unable to have the French reimburse him for his expenses.[39]

Due to his growing debt, it became impossible for Clark to continue holding his land which became subject to seizure. Much of his land was deeded to friends or transferred to family members where it could be held for him, rather than lost to the creditors.[40] After a few years, the lenders and their assigns closed in and deprived the veteran of almost all of the property that remained in his name. Clark, once the largest landholder in the Northwest Territory, was left with only a small plot of land in Clarksville, where he built a small gristmill which he worked with two African American slaves.[41] Clark lived on for another two decades, and continued to struggle with alcohol abuse, a problem which had plagued him on-and-off for many years. He was very bitter about his treatment and neglect by Virginia, and blamed his misfortune on them.[42]

The Indiana Territory chartered the Indiana Canal Company in 1805 to build a canal around the Falls of the Ohio, near Clarksville. Clark was named to the board of directors and was part of the surveying team that assisted in laying out the route of the canal. The company collapsed the next year before construction could begin, when two of the fellow board members, including Vice President Aaron Burr, were arrested for treason. Burr was plotting to seize Louisiana from Spain and open the Mississippi to the Americans. A large part of the company's $1.2 million($60.5 million in 2009 chained dollars) in investments was unaccounted for, and where the funds went was never determined.[43]

Return to Kentucky

In 1809, Clark suffered a severe stroke. Falling into an operating fireplace, he suffered a burn on one leg so severe as to necessitate the amputation of the limb.[44] It was impossible for Clark to continue to operate his mill, so he became a dependent member of the household of his brother-in-law, Major William Croghan, a planter at Locust Grove farm eight miles (13 km) from the growing town of Louisville.[45] During 1812, the Virginia General Assembly granted Clark a pension of four-hundred dollars per year, and finally recognized his services in the Revolution by granting him a ceremonial sword.[46] After a second stroke, Clark died at Locust Grove, February 13, 1818, and was buried at Locust Grove Cemetery two days later[47]

In his funeral oration, Judge John Rowan succinctly summed up the stature and importance of George Rogers Clark during the critical years on the Trans-Appalachian frontier: "The mighty oak of the forest has fallen, and now the scrub oaks sprout all around."[48]

Clark's body was exhumed along with the rest of his family members on October 29, 1869, and reburied at Cave Hill Cemetery in Louisville.[49][50]

Several years after Clark's death the state of Virginia granted his estate $30,000 ($568,853 in 2009 chained dollars) as a partial payment on the debts that they owed him.[51] The government of Virginia continued to find debt to Clark for decades, with the last payment to his estate being made in 1913.[52] Clark never married and he kept no account of any romantic relationships, although his family held that he had once been in love with Teresa de Leyba, sister of Don Fernando de Leyba, the Spanish Governor of Louisiana. Writings from his niece and cousin in the Draper Manuscripts attest to their belief in Clark's lifelong disappointment over the failed romance.[53]

Legacy

On May 23, 1928, President Calvin Coolidge ordered a memorial to George Rogers Clark to be erected in Vincennes. Completed in 1933, the George Rogers Clark Memorial, built in Roman Classical style, stands on what was then believed to be the site of Fort Sackville, and is now the George Rogers Clark National Historical Park. It includes a statue of Clark by Hermon Atkins MacNeil.[54] On February 25, 1929, to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the surrender of Fort Sackville, the U.S. Post Office Department issued a 2-cent postage stamp that depicted the surrender.[55] In April 1929, the Paul Revere Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution of Muncie, Indiana erected a monument to George Rogers Clark on Washington Avenue in Fredericksburg, Virginia. The marker doesn't identify the connection between General Clark and Fredericksburg, so this choice of location is currently a mystery.[56] In 1975, the Indiana General Assembly designated February 25 George Rogers Clark Day in Indiana.[55] Built in 1929, the George Rogers Clark Memorial Bridge (Second Street Bridge) carries U.S. Highway 31, over the Ohio River at Louisville, Kentucky.

Other statues of Clark can be found in:

- Metropolis, Fort Massac, Illinois, by sculptor Leon Hermant, placed by the Daughters of the American Revolution in the early 1900s.

- Louisville, Kentucky, by sculptor Felix de Weldon, at Riverfront Plaza/Belvedere, next to the wharf on the Ohio River.

- Springfield, Ohio, by Charles Keck at the site of the Battle of Piqua.

- Charlottesville, Virginia, by Robert Aitken on the grounds of the University of Virginia.

- Quincy, Illinois, in Riverview Park, on the eastern bank of the Mississippi River.

- Indianapolis, Indiana, by sculptor John H. Mahoney, on Monument Circle

Places named for Clark include:

- Clark County, Illinois

- Clarksville, Clark County, Indiana

- Clark County, Kentucky, which is the home of George Rogers Clark High School.

- Clark County, Ohio, which is the home of Clark State Community College.

- Clarksburg, West Virginia

- Clarksville, Tennessee

- Clark Street (Chicago)

And finally, schools named after Clark include:

- George Rogers Clark Elementary School in Clarksville, Indiana,

- George Rogers Clark Middle/High School in Hammond, Indiana,

- George Rogers Clark High School in Winchester, Kentucky

- Clark Middle School in Winchester, Kentucky

- Clark Elementary School in Charlottesville, Virginia

- George Rogers Clark Middle School in Vincennes, Indiana

- George Rogers Clark Elementary School of Chicago.[57]

- George Rogers Clark Elementary School in Paducah, Kentucky

See also

- History of Louisville, Kentucky

- List of Louisvillians

- General Jonathan Clark, his older brother

Notes

- ^ Palmer, 3

- ^ English, Vol 1, pg 35-38

- ^ Palmer, 4–5

- ^ English, 1:56

- ^ Palmer, 51

- ^ English, 1:60

- ^ Palmer, 56

- ^ Palmer, 74

- ^ English, 1:70-71

- ^ Harrison, 9

- ^ Palmer, 394

- ^ English, 1:87

- ^ English, 1:92

- ^ English 1:168

- ^ English, 1:234

- ^ Palmer, IV

- ^ a b Palmer, 391–394

- ^ Palmer, 400 & 421

- ^ English, 2:682

- ^ English, 2:730

- ^ Palmer, 424

- ^ Harrison, 93–94

- ^ English, 2:758-760

- ^ Palmer, 79

- ^ Harrison, 118

- ^ Palmer, IIX

- ^ Harrison, 101

- ^ English, 2:790–791

- ^ Harrison, 101

- ^ James, 325

- ^ Harrison, 102

- ^ a b Harrison, 104

- ^ English, 2:800-803

- ^ Indiana Historical Bureau. "Plat of Clark's Grant". IN.gov. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- ^ Harrison, 105

- ^ English, 2:818

- ^ English, 2:821–822

- ^ James, 425

- ^ Harrison, 106

- ^ Harrison, 100

- ^ English, 2:862

- ^ Harrison, 105

- ^ Dunn, 382–383

- ^ English, 2:869

- ^ English, 2:882

- ^ "Clark after the Revolution". Indiana Historical Bureau. Retrieved 2008-08-25.

- ^ English, 2:887

- ^ "George Rogers Clark National Historic Park". National Parks Service. Retrieved 2009-03-22.

- ^ English, 2:897. Several bodies were exhumed before Clark's skeleton was finally identified by the military uniform, amputated leg, and red hair. English stated an exhumed date of 1889

- ^ "Clark's Death". Indiana Historical Bureau. Retrieved 2008-08-25., The IHB states the exhumed date to be in 1869.

- ^ Harrison, 100

- ^ Harrison, 98

- ^ Palmer, 297

- ^ "George Rogers Clark National Historic Park". National Parks Service. Retrieved 2008-08-25.

- ^ a b "Celebrating Clark". Indiana Historical Bureau. Retrieved 2008-08-25.

- ^ "George Rogers Clark Historical Marker". The Historical Marker database. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

- ^ "George Rogers Clark Elementary School". Retrieved 2008-08-28.

References

- Dunn, Jacob Piatt (1919). Indiana and Indianans. Chicago & New York: American Historical Society.

- English, William Hayden (1896). Conquest of the Country Northwest of the River Ohio, 1778–1783, and Life of Gen. George Rogers Clark. Vol. 2 Volumes. Indianapolis: Bowen-Merrill.

- Harrison, Lowell H (1976; Reprinted 2001). George Rogers Clark and the War in the West. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-9014-2.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - James, James Alton (1928). The Life of George Rogers Clark. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Palmer, Frederick (2004). Clark of the Ohio: A life of George Rogers Clark. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 0766181391.

Further reading

- Bakeless, John (1957). Background to Glory: The Life of George Rogers Clark. Lincoln:University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-6105-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|printing=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|pubsliher=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Bodley, Temple (1926). George Rogers Clark: His Life and Public Services. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Butterfield, Consul Willshire (1904). History of George Rogers Clark's Conquest of the Illinois and the Wabash Towns, 1778 and 1779. Columbus, Ohio: Heer.

- Carstens, Kenneth C. and Nancy Son Carstens, eds (2004). The Life of George Rogers Clark, 1752–1818: Triumphs and Tragedies. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger. ISBN 0-313-32217-1.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

- The George Rogers Clark Heritage Association

- Route of George Rogers Clark across Illinois

- Indiana Historical Bureau, including Clark's memoir

- Clark Family Papers -- Missouri History Museum Archives

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)

- 1752 births

- 1818 deaths

- Burials at Cave Hill Cemetery

- Clark County, Ohio

- Clarksburg, West Virginia

- Clarksville, Indiana

- Deaths from stroke

- English Americans

- History of Louisville, Kentucky

- Illinois in the American Revolution

- Indiana in the American Revolution

- Kentucky militiamen in the American Revolution

- Militia generals in the American Revolution

- Mercenaries

- People from Louisville, Kentucky

- People in Dunmore's War

- People of Virginia in the American Revolution

- People from Clark County, Indiana

- Scottish Americans