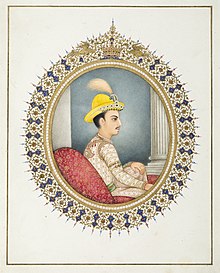

Girvan Yuddha Bikram Shah

| Girvan Yuddha Bikram Shah | |

|---|---|

| King of Nepal | |

| |

| Reign | 8 March 1799 – 20 November 1816 |

| Coronation | 8 March 1779[1] |

| Predecessor | Rana Bahadur Shah |

| Successor | Rajendra Bikram Shah |

| Born | 19 October 1797 Basantapur, Nepal |

| Died | 20 November 1816 (aged 19)(smallpox) Basantapur, Nepal |

| Spouse | Sidhi Laxmi Devi Shah Gorakshya Rajya Laxmi Devi Shah Kritirekha |

| Issue | Narendra Bikram Shah Rajendra Bikram Shah Satyarupa Rajya Laxmi Devi Subhagyasundari Rajya Laxmi Devi |

| Dynasty | Shah dynasty |

| Father | Rana Bahadur Shah |

| Mother | Kantavati Devi |

| Religion | Hinduism |

Girvan Yuddha Bikram Shah (Template:Lang-ne) (19 October 1797 – 20 November 1816), also called Girvanyuddha Bikrama Shah, was fourth King of Nepal from 1799 to 1816. Although he was not the legitimate heir to the throne his father made him the heir for being the son of his favourite wife Kantavati Devi.

He was the son of King Rana Bahadur Shah, and ascended the throne at the age of 1 and 1/2 years when his father abdicated to become an ascetic. He ruled under the regency of Queen Lalit Tripura Sundari and Prime Minister Bhimsen Thapa. He died at age 19 and was succeeded by his young son Rajendra Bikram Shah.

Anglo-Nepalese War

The Gorkha War (1814–1816), or the Anglo–Nepalese War, was fought between the Kingdom of Nepal and the British East India Company as a result of border disputes and ambitious expansionism of both the belligerent parties. The war ended with the signing of the Treaty of Sugauli in 1816, which ceded around a third of Nepal's territory to the British. Most of the ceded territories had been acquired by Nepal by war only in the last 10 to 20 years from other kingdoms that had never been a part of Nepal.

The British were the invading forces, while the Nepalese maintained a defensive position. The British attacked in two successive waves of invasion. It was the most expensive war waged during the governorship of Lord Moira.

Battle of Makwanpur Gadhi

Colonel[2] Ranabir Singh Thapa, brother of Bhimsen Thapa, was to be the Sector Commander of Makawanpur-Hariharpur axis. He was given a very large fortress and about 4,000 troops with old rifles and a few pieces of cannons. But the British could not move forward from the border. Colonel Ranabir Singh Thapa had been trying to lure the enemies to his selected killing area. But Major General Wood would not venture forward from Bara Gadhi and he eventually fell back to Betiya.

Battle of Jitgadh

With the help of an ousted Palpali king, Major General Wood planned to march on Siuraj, Jit Gadhi and Nuwakot with a view to bypass the Butwal defenses, flushing out minor opposition on the axis, and assault Palpa from a less guarded flank. Nepalese Colonel Ujir Singh Thapa had deployed his 1200 troops in many defensive positions including Jit Gadhi, Nuwakot Gadhi and Kathe Gadhi. The troops under Colonel Ujir were very disciplined and he himself was a dedicated and able commander. He was famous for exploiting advantage in men, material, natural resources and well versed in mountain tactics. The British advance took place on 22nd Poush1871 BS (January 1814 AD) to Jit Gadh. While they were advancing to this fortress, crossing the Tinau River, the Nepalese troops opened fire from the fortress. Another of the attackers’ columns was advancing to capture Tansen Bazar. Here too, Nepalese spoiling attacks forced the General to fall back to Gorakhpur. About 70 Nepalese lost their lives in Nuwakot Gadhi. Meanwhile, more than 300 of the enemy perished.

Battle of Hariharpur Gadhi

No special military action had taken place in Hariharpur Gadhi fortress in the first campaign. Major General Bannet Marley and Major General George Wood had not been able to advance for an offensive against Makawanpur and Hariharpur Gadhi fortresses.

Battle of Nalapani

The Battle of Nalapani was the first battle of Anglo-Nepalese War. The battle took place around the Nalapani fort, near Dehradun, which was placed under siege by the British between 31 October and 30 November 1814. The fort's garrison was commanded by Captain Balbhadra Kunwar, while Major-General Rollo Gillespie, who had previously fought at the Battle of Java, was in charge of the attacking British troops. The failure to obey the field orders by his men led Gillespie to be killed on the very first day of the siege while rallying his men. Despite considerable odds, both in terms of numbers and firepower, Balbhadra and his 600-strong garrison successfully held out against more than 3,000 British troops for over a month.

After two costly and unsuccessful attempts to seize the fort by direct attack, the British changed their approach and sought to force the garrison to surrender by cutting off the fort's external water supply. Having suffered three days of thirst, on the last day of the siege, Balbhadra, refusing to surrender, led the 70 surviving members of the garrison in a charge against the besieging force. Fighting their way out of the fort, the survivors escaped into the nearby hills. The battle set the tone for the rest of the Anglo-Nepalese War, and a number of later engagements, including one at Jaithak, unfolded in a similar way.

The experience at Nalapani so discomforted the British that Lord Hastings so far varied his plan of operations as to forego the detachment of a part of this division to occupy Gurhwal.[3] He accordingly instructed Colonel Mawbey to leave a few men in a strong position for the occupation of the Doon and to carry his undivided army against Amar Singh's son, Colonel Ranajor Singh Thapa, who was with about 2300 elite of the Gurkha army, at Nahan.[3] It was further intended to reinforce the division considerably; and the command was handed over to Major-General Martindell.[3] In the mean time Colonel Mawbey had led back the division through the Keree pass, leaving Colonel Carpenter posted at Kalsee, at the north western extremity of the Doon.[4] This station commanded the passes of the Jumna on the main line of communication between the western and eastern portions of the Gurkha territory, and thus was well chosen for procuring intelligence.[4]

Battle of Jaithak

Major General Martindale now joined the force and took over command. He occupied the town of Nahan on 27 December, and started his attach on the fort of Jaithak. The fort had a garrison of 2000 men under the command of Ranajor Singh Thapa, the son of the Amar Singh Thapa. The first assault ended in disaster, with the Nepalese successfully warding off the British offensive. The second managed to cut off the water supply to the fort, but could not capture it mainly because of the exhausted state of the troops and shortage of ammunition. Martindale lost heart and ordered a withdrawal. Jaithak was eventually captured much later in the war, when Ochterlony had taken over the command.[5]

A single day of battle at Jaithak cost the British over three hundred men dead and wounded and cooled Martindell’s ardour for battle. For over a month and a half, he refused to take any further initiative against the Nepalese army. Thus by mid-February, of the four British commanders the Nepalese army had faced till that time, Gillespie was dead, Marley had deserted, Wood was harassed into inactivity, and Martindell was practically incapacitated by over-cautiousness. It set the scene for Octorloney to soon show his mettle and change the course of the war.

Sughauli Treaty

The Treaty of Sugauli was ratified on 4 March 1816. As per the treaty, Nepal lost Sikkim (including Darjeeling), the territories of Kumaon and Garhwal, and most of the lands of the Terai. The Mechi River became the new eastern border and the Mahakali river the western boundary of the kingdom. The British East India Company would pay 200,000 rupees annually to compensate for the loss of income from the Terai region. Kathmandu was also forced to accept a British Resident.[6] The fear of having a British Resident in Kathmandu ultimately proved to be unfounded, as the rulers of Nepal managed to isolate the Resident to such an extent as to be in virtual house arrest.

The Terai lands, however, proved difficult for the British to govern and some of them were returned to the kingdom later in 1816 and the annual payments accordingly abolished.[7] However even after the conclusion of the Anglo-Nepalese War, the border issue between the two states was not yet settled. The boundary between Nepal and Oudh was not finally adjusted until 1830; and that between Nepal and the British territories remained as a matter of discussion between the two Governments for several years later.[8]

The British never had the intention to destroy either the existence or the independence of a state which was usefully interposed between them and the dependencies of China.[9] Lord Hastings had given up his plan to dismember Nepal from fear of antagonising China – whose vassal Nepal in theory was. In 1815, while British forces were campaigning in far western Nepal, a high-ranking Manchu official advanced with a large military force from China to Lhasa; and the following year, after the Anglo-Nepalese treaty had been signed, the Chinese army moved south again, right up to Nepal’s frontier. The Nepalese panicked, because memories were still vivid of the Chinese invasion of 1792, and there was a flurry of urgent diplomatic activity. Hastings sent mollifying assurances to the imperial authorities, and ordered the British Resident, newly arrived in Kathmandu, to pack his bags and be ready to leave at once if the Chinese invaded again.[10]

References

- ^ Royal Ark

- ^ The use of English terms for their grades of command was common in the Nepalese army, but the powers of the different ranks did not correspond with those of the British system. The title of General was assumed by Bhimsen Thapa, as Commander-in-chief, and enjoyed by himself alone; of Colonels there were three or four only; all principal officers of the court, commanding more than one battalion. The title of Major was held by the adjutant of a battalion or independent company; and Captain was the next grade to colonel, implying the command of a corps. Luftun, or Lieutenant, was the style of the officers commanding companies under the Captain; and then followed the subaltern ranks of Soobadar, Jemadar, and Havildar, without any Ensigns. (Prinsep, p. 86-87)

- ^ a b c Prinsep, p. 94.

- ^ a b Prinsep, p. 95.

- ^ India-Board (8 Nov 1816).

- ^ Oldfield, p. 304-305.

- ^ Oldfield, p. 306.

- ^ Anon (1816), p. 428.

- ^ Pemble, Forgetting and remembering Britain's Gurkha War, p.367.