Glauberg

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (August 2014) |

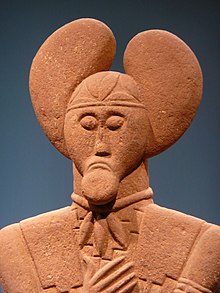

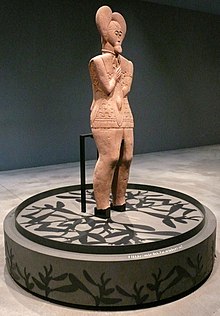

The "Prince of Glauberg" (c. 500 BC) | |

| Location | Glauburg, Hesse |

|---|---|

| Region | Germany |

| Type | Burial mounds, Circular rampart or Oppidum |

| History | |

| Periods | Iron Age |

| Cultures | Celts, La Tène |

| Site notes | |

| Public access | Yes |

The Glauberg is a Celtic oppidum in Hesse, Germany consisting of a fortified settlement and several burial mounds, "a princely seat[1] of the late Hallstatt and early La Tène periods."[2] Archaeological discoveries in the 1990s place the site among the most important early Celtic centres in Europe. It provides unprecedented evidence on Celtic burial, sculpture and monumental architecture.

Location and topography

Geologically, the Glauberg, a ridge (271 m asl) on the east edge of the Wetterau plain, is a basalt spur of the Vogelsberg range. Rising about 150 m above the surrounding areas, it is located between the rivers Nidder and Seeme and belongs to the community of Glauburg. The hilltop forms a nearly horizontal plateau of 800 by 80–200m. Its southwest promontory is known as Enzheimer Köpfchen. To the northwest, the Glauberg slopes steeply down towards the Nidder valley and, in the south, it is connected with undulating uplands. The plateau contained a small perennial pond, which was not fed by springs but simply by surface runoff.[3] The hill is surrounded by springs and fertile land.[4]

History of archaeological research

The presence of ancient ruins on the Glauberg plateau has long been known, though they were credited to the Romans. The discovery of a fragment of an early La Tène torc in 1906, confirmed the prehistoric nature of the site. Systematic archaeological research began in 1933–1934 with an excavation led by Heinrich Richter (1895–1970) which focused on the fortification.[5] Further studies directed by F.-R. Hermann began in 1985 and continued until 1998. It was during this phase that the important burial mound was examined.[6] The settlement history of the Glauberg and its area in Celtic times (Hallstatt and early La Tène periods) was the focus of a research project (2004–2006) by the 'Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft'.[7]

Summary of settlement history

The topographic location marks the Glauberg as a long-term focus of human activity. It combines access to fertile arable land and water with an easily defensible site and a strategic location along several natural traffic routes. Thus, it is not surprising that the hill was the site of human occupation long before and long after its Celtic phase, well into the medieval period.[8]

The Glauberg plateau was first settled in the Neolithic era (c. 4500 BC) by people of the Rössen culture. This was followed by a large settlement of the Michelsberg phase (4000 BC). Michelsberg hilltop fortifications are known elsewhere, so it is possible that the hill was fortified for the first time at that stage. The hill was also settled by the late Bronze Age Urnfield culture (1,000–800 BC). During the Celtic late Hallstatt/early La Tène period, the Glauberg became a centre of supra-regional importance. At this time, it was the seat of an early Celtic prince. Extensive fortifications were erected.

During the Roman occupation of Germany, the Glauberg remained unoccupied, probably due to its proximity (5 km) to the fortified Limes Germanicus border. In the 4th and 5th centuries AD, it was reoccupied and became a regional centre once again, as the seat of a local king of the Alamanni. From the 7th to the 9th century, it was the site of a large Frankish fortification. Its importance grew throughout this time, and the fortifications were renewed and extended considerably.

In the 12th and 13th centuries, the Glauberg was incorporated into the Staufer system of castles, perhaps in an attempt to foster the growth of an urban centre. The fortifications were renovated again, and a tower-like castle was erected on the edge of the plateau; its arched romanesque doorway survives. The whole plateau was settled at this time, medieval foundations of walls, wells and basements survive especially at its north edge. The destruction of that castle, and with it the end of human occupation on the hill, probably occurred in 1256.

Celtic fortification (oppidum)

The earliest known fortifications might be pre-Celtic, but they reached a high point in terms of size and elaboration around the 6th or 5th century BC. They remained in use until the 2nd or 1st century BC. Their extent and dimensions mark the Glauberg as one of a network of fortified sites (or oppida) that covered most of south and west central Germany.

The northeast edge of the hill, where the slope is least severe, was disconnected from the adjacent ground by the erection of a massive ditch and bank, perhaps originally forming a promontory fort. The southern and northern edges were also fortified with walls. The walling techniques included drystone walling, the murus gallicus (a typical Celtic technique of wood and stone) and perhaps also mudbrick.

The small hilltop pond would not have sufficed to ensure water supply for the population of so large a settlement. For this reason, an annex was added to the north, with two walls running downslope, enclosing an additional triangular area of 300 x 300 m, including a spring. The point of that annex contained a huge water reservoir, measuring 150 by 60 m. At this time, the fortification was 650 m long, nearly 500 m wide, and enclosed an area of 8.5 ha.

At least two gates, a main one to the northeast and a smaller one to the south, gave access to the interior. They are fairly complex in shape, designed to make access for a possible attacker more difficult. An outer fortification was placed beyond the northeast edge of the oppidum. Walls or banks to the south probably played no defensive role.[9]

Such settlements probably housed populations numbering in the thousands. For this reason, combined with their centralising economic role, Celtic oppida are sometime described as proto-urban. Nonetheless, little is known about settlement and other activity on the interior of the site. Evidence from the sites at Manching or Oberursel-Oberstedten suggests that there was probably a village or town-like settlement with houses, workshops and storage areas.

Sites associated with the oppidum

Like other such sites, the Glauberg oppidum is connected with several other contemporary sites/complexes in its immediate vicinity:

"Princely" burial mounds

During an exploratory overflight in 1988, local amateur historians recognised the traces of a large tumulus in a field 300 m south of the oppidum. Between 1994 and 1997, the State Archaeological Service of Hesse excavated it.[10] The mound (mound 1) originally had a diameter of nearly 50 m and a height of 6 m. It was surrounded by a circular ditch 10 m wide. At the time, it must have been a visually extremely striking monument. The tumulus contained three features. An empty pit was placed at the centre, perhaps to mislead potential looters. To the northwest, a wooden chamber of 2 x 1 m contained an inhumation, and to the southeast, a cremation burial had been placed in some kind of wooden container. Cremations are more commonly associated with the Halstatt phase, inhumation with the La Tène one.

The occupants of both graves were warriors, as indicated by their accompanying material: swords and weaponry. The chamber with the inhumation was extremely well preserved and had never been looted. For this reason, it was decided to remove the whole chamber en bloque and excavate it more slowly and carefully in the State Service laboratory at Wiesbaden. The finds from the main burial chamber, each carefully wrapped in cloth, include a fine gold torc and a bronze tubular jug that had contained mead.

A second tumulus (mound 2), 250 m to the south, was discovered later by geophysical survey. Erosion and ploughing had made it totally invisible. About half the size of mound 1, it also contained a warrior, accompanied by weapons, a decorated fibula and belt, and a gold ring.

The high quality of the tomb furnishings as well as other features associated with them indicate that the graves, and their occupants, were of extremely high status. They are therefore classed as "princely" burials, on a par with other well-known finds, including those at Vix (Burgundy, France), and Hochdorf (Baden-Württemberg, Germany).

Earthworks and processional road

A number of earth features (banks and ditches) are located south of the oppidum, some closely associated with mound 1. They appear to play no defensive role. A small square ditch west of the mound is associated with several other features and a number of large postholes, perhaps suggesting a shrine or temple. Most strikingly, a processional way 350 m long, 10 m wide and flanked by deep ditches approached the tumulus from the southeast, far beyond the settlement perimeter. This was associated with further banks and ditches extending over an area of nearly 2 by 2 km. They also contained at least two burials, as well as the statue described below.

The lack of a defensive function and the focus on the burial mounds have led to the suggestion that the enclosure and road system had a ritual or sacred significance. Such a complex is, so far, entirely unparalleled in Celtic Europe.[11]

The Keltenfürst (Celtic prince) of Glauberg

Much international attention was attracted especially by the discovery of an extremely rare find, a life-sized sandstone statue or stele, dating from the 5th century BC, which was found just outside the larger tumulus.[12] The stele, fully preserved except for its feet, depicts an armed male warrior. It measures 186 cm in height and weighs 230 kg.[13]: 68 It is made from a type of sandstone available within a few kilometres of Glauberg. Much detail is clearly visible: his trousers, composite armour tunic, wooden shield and a typical La Tène sword hanging from his right side. The moustachioed man wears a torc with three pendants, remarkably similar to the one from the chamber in mound 1, several rings on both arms and one on the right hand. On his head, he wears a hood-like headdress crowned by two protrusions, resembling the shape of a mistletoe leaf. Such headdresses are also known from a handful of contemporary sculptures. As mistletoe is believed to have held a magical or religious significance to the Celts, it could indicate that the warrior depicted also played the role of a priest.[12] Fragments of three similar statues were also discovered in the area. It is suggested that all four statues once stood in the rectangular enclosure. Perhaps they were associated with an ancestor cult.

Parallels to the Glauberg warrior statue exist in the form of stelai from other La Tène sites, such as the Holzgerlingen figure (Stuttgart State Museum), a pillar-stele from Pfalzfeld (St Goar), the Warrior of Hirschlanden and others.

Postholes

The purpose of the 16 postholes associated with the mound and enclosure is still undiscovered. First theories had been, that they build an astronomical calendar, to determine seasonal events or holidays.[14] Recent investigations showed, that they had been build later than the mounds, giving room for interpreting them as part of architectural elements like bridges, arches and temple structures.[15]

Southern Hesse - a Celtic landscape

The Glauberg is not isolated within its time and area, although it is the most northeasterly site of its type known at present. But several other important Celtic population centres or oppida are known from the Rhein-Main Region and Central Hesse. Two important fortifications, those at Dünsberg near Giessen and Heidetränk Oppidum (one of the largest urban settlements in Celtic Europe) near Altkönig in the Taunus mountains are visible from Glauberg. Nearby is also the Celtic salt industry at Bad Nauheim.[16]

Significance

The discoveries at Glauberg have added several new perspectives to the understanding of early Celtic Europe. They have somewhat expanded the known extent of early La Tène civilization, they have thrown much light on the early development of Celtic art, and most importantly of sculpture. The warrior figure and other material support suggestions of links and contact with the civilisations of the Mediterranean at this early point. The ritual complex surrounding the tomb has added a whole new monument type to European prehistory.[17]

Sites like Glauberg, sometimes referred to as Fürstensitze (seats of princes), indicate a parallel development of social hierarchies developing across late Hallstatt Europe. Elite sites, characterised by massive fortifications, the presence of imported materials and of elaborate burials developed along the important trade routes across the continent. Glauberg must now be considered a proto-urban centre of power, trade and cult, of similar importance to such sites as Bibracte, or Manching, but especially of other "princely" fortified settlements, such as Heuneburg, Hohenasperg and Mont Lassois.

Archaeological park and museum

An archaeological park has been built, with the aim of making the site and its context accessible and comprehensible to visitors and providing a space for exhibiting the finds locally. Previously, some of the finds, including the statue, were on display in the Hessian State Museum at Darmstadt.

Construction for the museum started in 2007, with completion originally projected for 2009. It opened on 5 May 2011.[18]

By November 2015, the museum had counted around 300,000 visitors and estimated the total number of people who had come to see the Keltenwelt (i.e. including those who just explored the 30 ha open air archaeological park) at around 500,000.[13]: 68

See also

- Celtic Hero from Bohemia

- Warrior of Hirschlanden

- Hochdorf Chieftain's Grave

- Heuneburg

- Keltenmuseum, Hallein

- Oppidum of Manching

- Vix and Mont Lassois

References

- ^ Prestige goods diagnostic of an elite habitation have not been found; the common designation of the Glauberg as a "princely seat" is based on the contents of the tombs located in a walled sanctuary at the foot of the southern slope.

- ^ R.K., in John T. Koch, ed., Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia, 2006, s.v. "Glauberg".

- ^ The watertight strata of clay that contained the pool were broken by demolition after World War II, and the pool drained. (Koch 2006).

- ^ [1]; [2]

- ^ The findings and documentation were accidentally destroyed in the closing days of World War II (Koch 2006).

- ^ www.fuerstensitze.de :: Landschaftsarchäologie Glauberg :: Projektbeschreibung

- ^ www.fuerstensitze.de :: Fürstensitz Glauberg

- ^ http://www.keltenfuerst.de/index_1.htm Besiedelung

- ^ For whole section on fortifications: F.-R. Herrmann 1990: Ringwall Glauberg; in: F.-R. Herrmann and A. Jockenhövel (eds.): Die Vorgeschichte Hessens, Stuutgart: Theiss, p. 385-387

- ^ For whole section, see http://www.keltenfuerst.de/index_1.htm Fürstengräber, also Frey and Herrmann 1998, Herrmann 2002

- ^ Keltenfürst

- ^ a b Information on statue: http://www.denkmalpflege-hessen.de/Keltenfurst/keltenfurst.html, Herrmann 1998

- ^ a b Allihn, Karen (April 2016). "Ein Jubiläum für den Keltenfürsten". Archäologie in Deutschland (in German). WBG. pp. 68–9.

- ^ Kelten in Hessen, State agency for the preservation of cultural heritage. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- ^ Offenbar doch kein Kalenderbauwerk. Rätselraten um keltische Pfosten auf dem Glauberg. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- ^ see e.g. the site gazeteer in F.-R. Herrmann & A. Jockenhövel 1990: Die Vorgeschichte Hessens, Stuttgart: Theiss, p. 305-505

- ^ Herrmann 2005

- ^ Eine Heimstatt für die Wetterauer Kelten. FAZ.NET. Accessed 5 May 2011.

Bibliography

- H. Baitinger, Der frühkeltische Fürstensitz auf dem Glauberg — Stand der Erforschung, DFG online publication 2006. Pdf

- H. Baitinger/F.-R. Herrmann, Statues of Early Celtic princes from Glauburg-Glauberg, Wetterau district, Hesse (D). In: B. Fagan (ed.), Archaeology now: great discoveries of our time (forthcoming).

- H. Baitinger/F.-R. Herrmann, Der Glauberg am Ostrand der Wetterau. Arch. Denkmäler Hessen 51 (3. ed. Wiesbaden 2007).

- F.-M. Bosinski/F.-R. Herrmann, Zu den frühkeltischen Statuen vom Glauberg. Ber. Komm. Arch. Landesforsch. Hessen 5, 1998/99 (2000) p. 41—48.

- O.-H. Frey/F.-R. Herrmann, Ein frühkeltischer Fürstengrabhügel am Glauberg im Wetteraukreis, Hessen. Bericht über die Forschungen 1994—1996. Germania 75, 1997, 459—550; also published separately (Wiesbaden 1998).

- F.-R. Herrmann, Der Glauberg am Ostrand der Wetterau. Arch. Denkmäler Hessen 51 (Wiesbaden 1985; 2nd ed. Wiesbaden 2000).

- F.-R. Herrmann, Keltisches Heiligtum am Glauberg in Hessen. Ein Neufund frühkeltischer Großplastik. Antike Welt 29, 1998, p. 345—348.

- F.-R. Herrmann, Der Glauberg: Fürstensitz, Fürstengräber und Heiligtum. In: H. Baitinger/B. Pinsker (Red.), Das Rätsel der Kelten vom Glauberg (Exhibition Cat. Frankfurt a. Main 2002) 90—107.

- F.-R. Herrmann, Glauberg — Olympia des Nordens oder unvollendete Stadtgründung? In: J. Biel/D. Krausse (Hrsg.), Frühkeltische Fürstensitze. Älteste Städte und Herrschaftszentren nördlich der Alpen? Internat. Workshop Eberdingen-Hochdorf 12./13. September 2003. Arch. Inf. Baden-Württemberg 51. Schr. Keltenmus. Hochdorf/Enz 6 (Esslingen 2005) p. 18—27.

- F.-R. Herrmann, Fürstengrabhügel 2 am Glauberg. Denkmalpfl. u. Kulturgesch. H. 3, 2006, p. 27 f.

- F.-R. Herrmann/O.-H. Frey, Die Keltenfürsten vom Glauberg. Ein frühkeltischer Fürstengrabhügel bei Glauburg-Glauberg, Wetteraukreis. Arch. Denkmäler Hessen 128/129 (Wiesbaden 1996) p. 8 ff.

- F.-R. Herrmann in: F.-R. Hermann/A. Jockenhövel (Hrsg.), Die Vorgeschichte Hessens (Stuttgart 1990) p. 385 ff.

- H. Richter, Der Glauberg (Bericht über die Ausgrabungen 1933—1934). Volk u. Scholle 12, 1934, p. 289—316.