Greeley House (Chappaqua, New York)

Greeley House | |

East profile and north (front) elevation, 2012 | |

| Location | Chappaqua, NY |

|---|---|

| Area | 0.3 acres (1,200 m2) |

| Built | 1864 |

| MPS | Horace Greeley TR |

| NRHP reference No. | 79003212[1] |

| Added to NRHP | April 19, 1979 |

The Greeley House is located at King (New York State Route 120) and Senter streets in downtown Chappaqua, New York, United States. It was built about 1820 and served as the home of newspaper editor and later presidential candidate Horace Greeley from 1864 to his death in 1872. In 1979 it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places along with several other properties nearby related to Greeley and his family.[1]

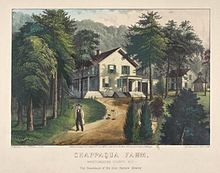

Built in the 1820s as a typical small farmhouse, it was expanded in the mid-19th century. Greeley, editor of the New-York Tribune, settled in Chappaqua shortly before the Civil War in the mid-19th century, living there with his family primarily during the summer. After a mob of citizens opposed to Greeley's abolitionist editorial stance threatened his wife at their earlier "House in the Woods," Greeley bought the farmhouse and moved his family there, near the hundred acres (40 ha) where he ran a small farm and practiced experimental agricultural techniques.

After the war, Greeley built a mansion called "Hillside House" to live in, but died along with his wife shortly after the 1872 presidential election, where he ran on the Liberal Republican line against incumbent Ulysses S. Grant, so his children lived there instead, pioneering the suburban lifestyle that was later to define Chappaqua and its neighboring communities. Both of Greeley's other houses burned down later in the 19th century, leaving the Greeley House the only one extant.[2]

It, too, was almost demolished after falling into serious neglect in the early 20th century. After its restoration in 1940, it was used as a restaurant and gift shop. Following another restoration effort in the early 21st century, it is now the offices of the New Castle Historical Society.

Building

The house is located on a one-third-acre (1,200 m2) lot in the corner between the two streets, at the bottom of a steep hill King descends from the east. It is at the eastern edge of downtown Chappaqua, an unincorporated hamlet of the town of New Castle nestled in a level area of a hilly region. The Saw Mill River, paralleled closely by the eponymous parkway and Metro-North Railroad's Harlem Line, are in a corridor 600 feet (180 m) to the west.[3]

To its west are one-story commercial buildings interspersed with parking lots. North and east, going uphill on King, are a church on the same side of the street, followed by houses of more modern construction. The local fire department headquarters are on the southeast, with New Castle's community center across Senter Street buffering the baseball fields beyond.[2]

A white wooden picket fence with a gate sets off the house from the sidewalk. The building itself is a two-story five-by-three-bay timber frame structure on a brick foundation sided in clapboard and topped by a shingled gabled roof pierced by two brick chimneys. A two-story flat-roofed extension projects from the south (rear) facade.

On the north (front) face, a two-story porch runs the full width of the house. Wooden steps lead up to it from the west, with a brick wheelchair ramp and modern aluminum railings providing access to the wooden deck from the east. Square wooden pillars rising to a molded cornice support the balustraded balcony level. The main entrance, at the west side, has a paneled wooden door flanked by two sidelights.

The windows are all set with six-over-six double-hung sash protected by a layer of storm glass, with minimal wooden sills and lintels. They are smaller on the first floor's north. All are flanked by louvered wooden shutters. At the east gable apex, split by the chimney, are two louvered lunettes; opposite there are just two more smaller six-over-six windows, with the middle bay on that facade left blind. The roofline is marked by a plain frieze and overhanging eave on the east and west sides.

Inside, the house follows a sidehall plan. The front room was originally the parlor, used for entertaining visitors, with the rear devoted to the dining room. The kitchen, with a small pantry, is in the rear. A small music room is on the north.[4]

Behind it are the stairs to the second floor. Above the pantry is a small bedroom, originally the maid's. Two larger bedrooms occupy the rest of the floor.[4]

History

The house has passed through four distinct periods. After its construction around 1820 as a modest farmhouse, Horace Greeley expanded it around the time of his arrival. His daughters maintained it after his death but largely lived elsewhere; since they sold it has been restored twice after nearly being demolished in the mid-20th century.

1820–1853: Before the Greeleys

The house was built by a farmer named Haviland around 1820. At the time it was a fairly simple, plain farmhouse, typical of the location and the period. While it was located on the main road through the area,[2] the center of Chappaqua was a mile (1.6 km) further up it, the area around the extant Quaker meetinghouse established by the settlement's founders eight decades earlier, now listed on the National Register as the Old Chappaqua Historic District.[5]

In the middle of the century the Harlem Valley Railroad, later part of the New York Central, was built along the Saw Mill River. The connection to New York changed Chappaqua's economy in two ways. The first was more immediately felt. Its farmers now had easy access to the markets of New York City to the south and began raising cash crops for it. Slowly the station and the neighborhood around it displaced the meetinghouse and its environs as the center f of social and public life in Chappaqua.[5]

1853–1872: Horace Greeley and his farm

The railroad also drew city residents to Chappaqua. In the early 1850s the Haviland house was extended by a third and its exterior decorated with the piazza-style porch and balcony, Victorian mantles and French windows. Similar decorative woodwork was added inside. In 1853, Horace Greeley, the editor of the New-York Tribune, bought the first part of what would eventually become a 78-acre (32 ha) farm nearby, much of it developed for that purpose either by Greeley himself or under his supervision[6] to use as an experimental farm, testing new agricultural techniques he wrote about in his column.[2] While he was frequently ridiculed for this in his day, due to his own professed previous ignorance of the subject, much of the advice he published in those columns was actually correct.[7]

Originally the farm was intended to be a summer residence for the Greeley family. His wife Mary, who like her husband was still distraught over the death of the couple's five-year-old son a year or so earlier,[8] had insisted that any such property had to have a spring-fed babbling brook, evergreen forest and be near the railroad. The Chappaqua property met two of those conditions, with a small bog standing in for the spring and brook.[7] In order to maximize the benefit of living in the countryside and escaping the hot city, Greeley built what his family came to refer to as the "House in the Woods" in what is still a wooded area southeast of the Church of Saint Mary the Virgin that his daughter Gabrielle had built early in the 20th century. Greeley's wife, however, found it shady and remote;[4] at one point, the couple invited young Spiritualist Kate Fox to live with them for four months while they attempted to contact the spirit of their dead son through seances.[8] The Greeleys were visited there by Henry David Thoreau, who shared Greeley's interest in land conservation. The Tribune published Thoreau's essay "The Succession of Forest Trees", after he and Greeley had an extensive discussion of forestry on one visit; the relationship continued to later years, when Greeley invited Thoreau to tutor the family's children.[9]

During the Civil War, Greeley continued his advocacy for abolition in the Tribune's editorial pages. A mob angered by this threatened the house, and Mary was prepared to blow it up if that happened again during the 1863 New York City draft riots.[10] The next year, he bowed to her complaints and bought the Haviland house, conspicuously located on the main road, from the estate of Caleb Sands, its later owner. The Greeleys continued its expansion, adding a music room to the north end. Still, the family lived in the house only during summers, shipping the piano up with them every spring. Greeley himself could only enjoy the house on weekends, due to the demands of his editorial position at the Tribune.[4]

After the war, Greeley continued to farm the property and test new agricultural methods. In 1870, a bumper crop of apples resulted in Greeley making more cider than he was able to sell. Later that year, on a hillside corner of the farm, now expanded to a hundred acres (40 ha), he built the first concrete barn in the nation.[11] It was later converted into a house and named Rehoboth, also listed on the National Register.[12]

Greeley began planning and building a new family home, Hillside House, located a short distance down the entrance road to the farm (which has since been extended and paved as Senter Street). It was completed in 1872, but before moving in he accepted the nomination of the Democratic and Liberal Republican parties to run against incumbent Ulysses S. Grant in that year's presidential election. After accepting the nominations he held a large picnic reception and luncheon on the southern portion of the farm, the land now the large lawn in front of Saint Mary. Mary Greeley died a few days before the election, in which Grant was the clear victor. The combination of those two events had a deleterious effect on Greeley's own health, and he died a few weeks later, before all the votes had been counted, the only time that has happened to a major presidential candidate.[12]

1873–1926: Gabrielle Greeley and subdivision

Now orphaned, the two Greeley daughters nevertheless returned to Chappaqua in the summer of 1873. They were accompanied by their older cousin, Cecilia Cleveland, and her mother. Cecilia later wrote a memoir of that summer in which she extolled the joys of the house, with its city amenities and country setting. It was a place where one could "dream away an entire morning", one she did not want to leave at the end of the season for the busier city. Her narrative depicts the emergence of an early suburban lifestyle, one that was going to continue all over Westchester County during the next decades. When the Greeleys had come to Chappaqua two decades earlier, they were practically alone in living this way. Since then others had discovered it, and Westchester had become a summer suburb.[13]

After that summer was over, Ida and Gabrielle moved into Hillside House. In 1875, the "House in the Woods" burned down, shortly before Ida married. Seven years later, she died.[14] In 1890, Hillside House also burned down, leaving the old farmhouse the only one of Horace Greeley's three Chappaqua homes standing. Two years later, Gabrielle Greeley and her husband, The Rev. Frank Glendenin, pastor of St. Peter's Episcopal Church in Manhattan, hired Ralph Adams Cram to remodel Rehoboth into a house. It became one of the centers of the increasingly more suburban community's social life.[12]

Early in the new century, the Glendenins began breaking up the farm. By 1900 the original railroad station (a few hundred feet north of the current station's platforms) was no longer adequate for the growing community's needs. Gabrielle settled a dispute over where to locate a new station by donating land on the southwest corner of the farm that was used to construct a new station,[15] opened in 1902 and now itself listed on the National Register. She stipulated that the area in front of it be left as a park to honor her father.[16]

A year afterwards, the Glendenin's daughter Muriel died at the age of five. They commissioned architect Morgan O'Brien to build a memorial chapel to her based on a medieval English church, Saint Mary the Virgin, outside London. It was completed in 1906 on the 4-acre (1.6 ha) parcel where her father had held his campaign picnic over 40 years earlier. Eight years later the memorial sculpture to Horace Greeley was installed in the small park across from the train station; in 1916 the Glendenins transferred the chapel to the Episcopal Diocese of New York, again with some stipulations, including one that they and their children be buried behind the church.[17]

1927–present: Restoration and subdivision

Gabrielle and her husband held on to the rest of the farm property until the late 1920s. She sold the house in 1926, ending 62 years of Greeley ownership. The rest of the farm was sold to a developer the next year, and subdivided into the commercial downtown it is now, completing the transformation of Chappaqua from the quiet country place to which Horace Greeley had escaped to practice farming into a modern suburb whose residents still lived in natural surroundings on large lots but commuted daily to jobs in the city.[14]

With the onset of the Great Depression of the 1930s the house was neglected and fell into disrepair. By 1940 it was looking as if it might have to be demolished. It was saved by two residents, who commissioned a local architect to preside over a restoration that year. One of them, Gladys Capen Mills, lived on the second floor and ran a small gift shop downstairs. For some of that time the kitchen was also used as a restaurant.[4]

In 1959 a local family bought it and expanded the gift shop to use the entire house, remodeling the interior for that purpose and adding the flat-roofed south addition. They remained in business there until 1998. After they closed, the New Castle Historical Society bought it. Throughout the first decade of the 21st century, two architects oversaw another restoration of the house, to an appearance closer to that which it had had during the Greeley era. It has been the society's offices since then.[4]

See also

References

- ^ a b "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- ^ a b c d "Cultural Resource Information System (CRIS)" (Searchable database). New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Retrieved 2016-04-01. Note: This includes Walter J. Gruber and Dorothy W. Gruber (March 1977). "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: Greeley House" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-04-01. and Accompanying 21 photographs

- ^ Ossining Quadrangle – New York – Westchester Co (Map). 1:24,000. USGS 7½-minute quadrangle maps. U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved May 14, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f "History of the Horace Greeley House". New Castle Historical Society. Retrieved May 15, 2013.

- ^ a b "Cultural Resource Information System (CRIS)" (Searchable database). New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Retrieved 2016-04-01. Note: This includes Lynn Beebe Weaver (October 1973). "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: Old Chappaqua Historic District" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-04-01. and Accompanying six photographs

- ^ Greeley, quoted at Ingersoll, Lurton Dunham (1873). The life of Horace Greeley: founder of the New York Tribune, with extended notices of many of his contemporary statesmen and journalists. Union Publishing Co. pp. 373–77. Retrieved May 15, 2013.

- ^ a b Linn, William Alexander (1903). Horace Greeley, Founder and Editor of the New York Tribune. D. Appleton & Co. p. 92. Retrieved May 15, 2013.

- ^ a b Horowitz, Mitch (2009). Occult America: White House Seances, Ouija Circles, Masons, and the Secret Mystic History of Our Nation. Random House Digital. p. 64. ISBN 9780553906981. Retrieved May 15, 2013.

- ^ Snay, Mitchell (2011). Horace Greeley and the Politics of Reform in Nineteenth-Century America. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 57. ISBN 9781442210028. Retrieved May 15, 2013.

- ^ Snay, 148.

- ^ Ingersoll, 384.

- ^ a b c Gruber, Walter and Dorothy (October 14, 1978). "Horace Greeley Related Sites Thematic Resources". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved April 3, 2013.

- ^ Panetta, Roger (2006). Roger Panetta (ed.). Westchester: the American suburb. Bronx, NY: Fordham University Press. p. 24. ISBN 9780823225941. Retrieved May 15, 2013.

- ^ a b "Greeley Family History". New Castle Historical Society. Retrieved May 16, 2013.

- ^ "Chappaqua Railway Station Cut Off". The New York Times. August 15, 1901. Retrieved May 16, 2013.

- ^ Gruber, Walter J. and Dorothy W. (August 28, 1977). "National Register of Historic Places nomination, Chappaqua Railroad Depot and Depot Plaza". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Retrieved May 16, 2013.

- ^ White, Ken. "SMTV – History". Church of Saint Mary the Virgin. Retrieved May 16, 2013.