Griot

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (June 2013) |

A griot (/ˈɡri.oʊ/; French pronunciation: [ɡʁi.o]), jali or jeli (djeli or djéli in French spelling) is a West African historian, storyteller, praise singer, poet and/or musician. The griot is a repository of oral tradition and is often seen as a societal leader due to his traditional position as an advisor to royal personages. As a result of the former of these two functions, he is sometimes also called a bard. According to Paul Oliver in his book Savannah Syncopators, "Though [the griot] has to know many traditional songs without error, he must also have the ability to extemporize on current events, chance incidents and the passing scene. His wit can be devastating and his knowledge of local history formidable". Although they are popularly known as "praise singers", griots may use their vocal expertise for gossip, satire, or political comment.

Griots today live in many parts of West Africa and are present among the Mande peoples (Mandinka, Malinké, Bambara, etc.), Fulɓe (Fula), Hausa, Songhai, Tukulóor, Wolof, Serer, Mossi, Dagomba, Mauritanian Arabs and many other smaller groups. The word may derive from the French transliteration "guiriot" of the Portuguese word "criado", or masculine singular term for "servant". These story-tellers are more predominant in the northern portions of West Africa.[citation needed]

In African languages, griots are referred to by a number of names: jeli in northern Mande areas, jali in southern Mande areas, guewel in Wolof, gawlo in Pulaar (Fula), and iggawen in Hassaniyan. Griots form an endogamous caste, meaning that most of them only marry fellow griots and that those who are not griots do not normally perform the same functions that they perform.

Francis Bebey writes about the griot in his book African Music, A People's Art (Lawrence Hill Books):

"The West African griot is a troubadour, the counterpart of the medieval European minstrel... The griot knows everything that is going on... He is a living archive of the people's traditions... The virtuoso talents of the griots command universal admiration. This virtuosity is the culmination of long years of study and hard work under the tuition of a teacher who is often a father or uncle. The profession is by no means a male prerogative. There are many women griots whose talents as singers and musicians are equally remarkable."[1]

Terms "griot" and "jali"

The Manding term jeliya (meaning "musicianhood") is sometimes used for the knowledge of griots, indicating the hereditary nature of the class. Jali comes from the root word jali or djali (blood). This word is also the title given to griots in areas corresponding to the former Mali Empire. Though the usage "griot" is far more common in English, some griot advocates such as Bakari Sumano prefer the term jeli.

In the Mali Empire

The Mali Empire (Malinke Empire), at its height in the middle of the 14th century, extended from central Africa (today's Chad and Niger) to West Africa (today's Mali and Senegal). The empire was founded by Sundiata Keita, whose exploits remain celebrated in Mali today. In the Epic of Sundiata, King Naré Maghann Konaté offered his son Sundiata a griot, Balla Fasséké, to advise him in his reign. Balla Fasséké is considered the founder of the Kouyaté line of griots that exists to this day.

Each aristocratic family of griots accompanied a higher-ranked family of warrior-kings or emperors, called jatigi. In traditional culture, no griot can be without a jatigi, and no jatigi can be without a griot; the two are inseparable and worthless without the other. However, the jatigi can accept a "loan" of his griot to another jatigi.

Most villages also had their own griot, who told tales of births, deaths, marriages, battles, hunts, affairs, and hundreds of other things.

In Mande society

In Mande society, the jeli was an historian, advisor, arbitrator, praise singer (patronage), and storyteller. Essentially, these musicians were walking history books, preserving their ancient stories and traditions through song. Their inherited tradition was passed down through generations. Their name, jeli, means "blood" in Manika language. They were said to have deep connections to spiritual, social, or political powers as music is associated as such. Speech is said to have power as it can recreate history and relationships.

Despite the authority of griots and the perceived power of their songs, griots are not treated as positively in west Africa as we may imagine. In fact, as Thomas A. Hale puts it: " Another [reason for ambivalence towards griots] is an ancient tradition that marks them as a separate people categorized all too simplistically as members of a “caste,” a term that has come under increasing attack as a distortion of the social structure in the region. In the worst case, that difference meant burial for griots in trees rather than in the ground in order to avoid polluting the earth (Conrad and Frank 1995:4-7). Today, although these traditions are changing, griots and people of griot origin still find it very difficult to marry outside of the group of artisans to which they belong."[2] Fortunately, such discrimination is now deemed illegal.

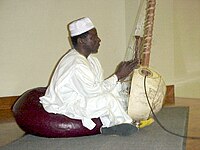

Popular instruments in griot culture

In addition to being singers and social commentators, griots are often skilled musicians. the kora, the khalam (also spelled xalam), the goje (called n'ko in the Mandinka language), the balafon and the ngoni.

The kora is a long-necked lute-like instrument.with 21 strings. The xalam is a variation of the kora, and usually consists of less than 5 string. Both have gourd bodies that act as resonator. The ngoni is also similar to these two instruments, and has 5 to 6 strings. The balafon is a wooden xylophone, while the goje is a stringed instruments that is played with a bow, much like a fiddle.

According to the Encyclopaedia Britannica: "West African plucked lutes such as the konting, khalam, and the nkoni (which was noted by Ibn Baṭṭūṭah in 1353) may have originated in ancient Egypt. The khalam is claimed to be the ancestor of the banjo. Another long-necked lute is the ramkie of South Africa."[3]

Today

Today, performing is one of the most common functions of a griot. Their range of exposure has widened, and many griots now travel all over the world singing and playing the kora or other instruments. Bakari Sumano, head of the Association of Bamako Griots in Mali from 1994 to 2003, was an internationally-known advocate for the importance of the griot in West African society.

In popular culture

Film

- In the Malian film Guimba the Tyrant (1995) directed by Cheick Oumar Sissoko, the storytelling is done through the village griot, who also provides comic relief.

- I was born as a Djeli (2007), a French documentary film written by Gwenaelle de Kergommeaux and Olivier Janin, directed by Cédric Condom

Music

- "Griot" is the name of an instrumental track on Jon Hassell and Brian Eno's ambient album Possible Musics (1980).

- Innercity Griots (1993) is the second album by Los Angeles hip-hop group Freestyle Fellowship, released through 4th & B'way Records. The group, consisting of four emcees — Aceyalone, P.E.A.C.E., Mikah 9 and Self Jupiter — received worldwide acclaim with their second project. Released during the prominent gangsta era of West Coast hip hop, Innercity Griots, along with albums such as The Pharcyde's Bizarre Ride II the Pharcyde and Del tha Funkee Homosapien's I Wish My Brother George Was Here, established an acclaimed era of alternative hip hop in California.[citation needed]

- "Griot" is the first song on the album Rubber Orchestras by Trinidadian poet and musician Anthony Joseph and The Spasm Band.[4]

- "From Filthy Tongue of Gods and Griots" is the second studio album by the New Jersey experimental hip-hop outfit Dälek (2002).

- "The Griot's Footsteps" [1] (Antilles/Verve) is a studio album by cornetist, composer, Graham Haynes.

- "The Griot" is the name of a track written and arranged by Armand Sabal-Lecco found on John Pantitucci's album Another World (1993).

- Alex Haley's book Roots makes references to a griot who passed down his family history through the oral tradition. When Haley traces his history, passing from his previous generation through the slave time, back to Africa, he thought there should be griots telling his history and the history of his ancestor, known in the family as "The African", who was captured in the bushes as he was seeking timber to make a talking drum. When Haley arrived in Africa to do research for his book, he believed he had found griots telling his history. Through them he learned the ancestor's identity: Kunta Kinte. Since he had first heard the story from his grandmother and later refreshed by his older cousin, he believed that they were griots in their own way until someone put the story to writing. He later learned that his cousin had died within an hour of his arrival at the village. (However, this story illustrates the problems and complexities of oral tradition, especially when approached without expert knowledge. In 1981, it was shown by Donald Wright[5] that the story of Kunta Kinte had been manufactured by a well-wisher. Following the publication of Roots, the story was being told in multiple versions with differing embellishments, having entered the stock of general stories.)

- In the late novels of the Ivorian writer Ahmadou Kourouma, Waiting for the Wild Beasts to Vote takes the form of a praise-song by the Sora, the griot, Bingo to the president-dictator of the fictitious République du Golfe. His final novel Allah is not Obliged prominently features a griot character.

- In Paule Marshall's Praisesong for the Widow, the protagonist Avatara (Avey) might take on some of the characteristics of a griot, especially in her commitment to passing on to her grandchildren her aunt's oral story of the Igbo Landing, in which Africans brought to the U.S. Sea Islands to be slaves promptly turned around and walked back to Africa over the water.

- Malian novelist Massa Makan Diabaté was a descendant and critic of the griot tradition. Though Diabaté argued that griots "no longer exist" in the classic sense,[6] he saw this tradition as one that could be salvaged through written literature. His fiction and plays blend traditional Mandinka storytelling and idiom with Western literary forms.

Notable griot performers

Burkina Faso

- Sotigui Kouyaté (Burkina Faso)

Côte d'Ivoire

- Tiken Jah Fakoly (Odienné)

Gambia

- Lamin Saho (Gambia)

- Foday Musa Suso (Gambia)

- Papa Susso (Gambia)

Guinea

- Ba Cissoko (Guinea)

- Djeli Moussa Diawara or Jali Musa Jawara (Guinea)

- Mory Kante

- N'Faly Kouyate (Guinea)

Mali

- Abdoulaye Diabaté

- Baba Sissoko

- Bako Dagnon

- Balla Tounkara

- Cheick Hamala Diabaté

- Djelimady Tounkara

- Habib Koité

- Mamadou Diabaté

- Sara M'Bodji

- Toumani Diabaté

- Babani Kone

Mauritania

Nigeria (northern)

- Dan Maraya Jos (Nigeria)

- Muhamman Shata (Nigeria)

Niger

- Etran Finatawa (Niger)

- Yacouba Moumouni (Niger)

Senegal

- Ablaye Cissokko (Senegal)

- Baaba Maal (Senegal)

- Nuru Kane (Senegam)

- Mansour Seck

- Youssou N'Dour (Senegal)

- Coumba Gawlo Seck (Senegal)

- Thione Seck (Senegal)

See also

- List of Sub-Saharan African folk music traditions

- Ahmadou Kourouma

- The skalds performed a similar function in Scandinavian societies.

- The bards performed a similar function in Welsh society, and the fili in Irish society.

- Marabout, another caste of the indigenous African societies

- Azmari

- Extempo

- Rapping

Notes

- ^ *Bebey, Francis (1969, 1975) African Music, A People's Art. Lawrence Hill Books. Brooklyn, NY.

- ^ Hale, Thomas A. (1997). "From the Griot of Roots to the Roots of Griot: A New Look at the Origins of a Controversial African Term for Bard" (PDF). Oral Tradition. 12 (2): 249–278 – via http://journal.oraltradition.org/.

{{cite journal}}: External link in|via= - ^ Robotham, Donald K.; Kubik, Gerhard (2012-01-27). "African Music". https://www.britannica.com/. Retrieved 2016-11-18.

{{cite web}}: External link in|website= - ^ Rubber Orchestras

- ^ *Wright, Donald R. (1981). "Uprooting Kunta Kinte: on the perils of relying on encyclopoaedic informants." History in Africa, vol. VIII.

- ^ Diabaté, Massa Makan (1985). L'assemblée des djinns (in French). Paris: Éditions Présence Africaine. pp. 62–63.

References

- Charry, Eric S. (2000). Mande Music: Traditional and Modern Music of the Maninka and Mandinka of Western Africa. Chicago Studies in Ethnomusicology. Includes audio CD. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Hale, Thomas A. (1998). Griots and Griottes: Masters of Words and Music. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press.

- Hoffman, Barbara G. (2001). Griots at War: Conflict, Conciliation and Caste in Mande. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press.

- Leymarie, Isabelle (1999). Les griots wolofs du Sénégal. Paris: Maisonneuve et Larose. ISBN 2706813571.

- Suso, Foday Musa, Philip Glass, Pharoah Sanders, Matthew Kopka, Iris Brooks (1996). Jali Kunda: Griots of West Africa and Beyond. Ellipsis Arts.

- I was born as a Djeli (2007), a French documentary film written by Gwenaelle de Kergommeaux and Olivier Janin, directed by Cédric Condom

External links

- Lavender, Catherine (2000). "African Griot Images." (Webpage for a course at CSI/CUNY)

- Salmons, Catherine A. (2004). Balla Tounkara "Griot"

- The Maninka and Mandinka Jali/Jeli

- The Ancient Craft of Jaliyaa

- Keita: The Heritage of the Griot - Film Notes

- The Griot Music documentary by Volker Goetze

- theGrio News The Grio is African-American News from NBC.

- Jeliya - The art of Jeli (being a griot)