Warsaw Ghetto boy

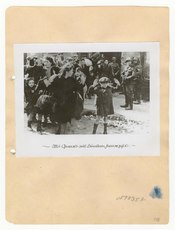

In the best-known photograph taken during the 1943 Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, a boy holds his hands over his head while SS-Rottenführer Josef Blösche points a submachine gun in his direction. The boy and others hid in a bunker during the final liquidation of the ghetto, but they were caught and forced out by German troops. After the photograph was taken, all of the Jews in the photograph were marched to the Umschlagplatz and deported to Majdanek extermination camp or Treblinka. The exact location and the photographer are not known, and Blösche is the only person in the photograph who can be identified with certainty. The image is one of the most famous photographs of the Holocaust,[a] and the boy came to represent children in the Holocaust, as well as all Jewish victims.[b]

Background

Warsaw is the capital of Poland. Before the war, about 380,000 Jews lived there, about one-quarter of the population. Upon the German invasion in September 1939, Jews began to be subject to anti-Jewish laws. In 1941, they were forced to move to the Warsaw Ghetto, which contained as many as 460,000 people in only 2.4% of the city's area. The official food ration was only 180 calories per person daily. Although being caught on the "Aryan" side of the city was an offense punishable by death, people survived by smuggling and running illegal workshops.[8]

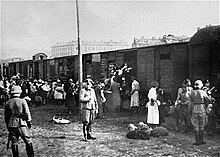

In mid-1942, most of the Jews in the Warsaw Ghetto were deported to the Treblinka extermination camp. In January 1943, when the Germans resumed deportations, the Jewish Combat Organization staged armed resistance. Jews began to dig bunkers and smuggle weapons into the ghetto. On 19 April 1943, about 2,000 soldiers under the command of SS and Police Leader Jürgen Stroop entered the ghetto with tanks in order to liquidate the ghetto. They expected to quickly defeat the poorly armed Jewish insurgents, but instead the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, the largest act of Jewish resistance against the Holocaust, dragged on for four weeks. The Germans had to set the ghetto on fire, pump poison gas into bunkers, and blast the Jews out of their positions in order to march them to the Umschlagplatz and deport them to Majdanek and Treblinka. According to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, "[t]his seemingly hopeless struggle... became one of the most significant occurrences in the history of the Jewish people".[8]

During the suppression of the uprising, Stroop sent daily communiqués to Higher SS and Police Leader Friedrich-Wilhelm Krüger in Kraków; Propaganda Company 689 and Franz Konrad took photographs to document the events.[9][10] Selected photographs and communiqués were compiled, along with a summary of German actions, as the Stroop Report, a personal souvenir for Heinrich Himmler.[11] The report was intended to promote Stroop's efficiency as a commander and excuse his failure to clear the ghetto quickly.[12] The report memorialized the supposed heroism of the SS men who participated in the suppression of the uprising, especially the sixteen who were killed by Jewish fighters.[3][13] More than 7,000 Jews were shot during the uprising, the vast majority noncombatants.[12]

The original title of the report was The Jewish Quarter of Warsaw is No More! (German: Es gibt keinen jüdischen Wohnbezirk in Warschau mehr!).[11] Reflecting Nazi propaganda, the report dehumanized the Jews, describing them as "bandits", "lice", or "rats" and their deportation and murder as a "cleansing action".[12][14] Instead of being killed or murdered, Jews were "destroyed".[3] Three copies of the report were made, for Himmler, Krüger, and Stroop.[11][12] One copy of the Stroop Report is held by the Institute of National Remembrance (IPN) in Warsaw. Another copy was entered into evidence at the Nuremberg Trials, although the photograph was not ultimately shown to the court. That copy is held by the United States National Archives and Records Administration (NARA).[13][15]

Photograph

The photograph was taken during the Warsaw Ghetto uprising (between 19 April and 16 May)[16] in the Warsaw Ghetto. An Internet forum discussion on the "Marki Commuter Railway" Association for Defending the Remnant of Warsaw cautiously identified the location as Nowolipie 34 from similarities in the architectural details, especially the downspout. These claims are discussed in a 2018 Polish-language book, Teraz ′43 (Now ′43), by Magdalena Kicińska and Marcin Dziedzic.[14] The photographer was either Franz Konrad or a member of Propaganda Company 689.[9][10] Albert Cusian, Erhard Josef Knoblach and Arthur Grimm served as photographers in Propaganda Company 689; Cusian may have claimed to have taken the photograph.[10] On trial in Poland, Konrad claimed to have taken photographs during the uprising only so that he could complain about Stroop's brutality to Adolf Hitler. The court did not accept this claim. Convicted of personally murdering seven Jews and deporting a thousand others to death camps, Konrad was sentenced to death and executed in 1952.[3][17]

The photograph depicts a group of Jewish men, women and children who have been forced out of a bunker by armed German soldiers. The original caption was "Forcibly pulled out of bunkers" (German: Mit Gewalt aus Bunkern hervorgeholt).[14] Most of the Jews are wearing ragged clothing and have few personal possessions. After being removed from the bunker, they were marched to the Umschlagplatz for deportation to an extermination camp. In the center of the photograph is a small boy wearing a newsboy cap and knee-length socks who appears six or seven years old. He holds his hands up in surrender as SS-Rottenführer Josef Blösche holds a submachine gun pointing downwards in his direction.[14][16][5] The photograph contains many opposites; as Richard Raskin put it: "SS vs. Jews, perpetrators vs. victims, military vs. civilians, power vs. helplessness, threatening hands on weapons vs. empty hands raised in surrender, steel helmets vs bare-headedness or soft caps, smugness vs. fear, security vs. doom, men vs. women and children".[1] According to Frédéric Rousseau, Stroop probably chose to include the photograph in the report because it showed his ability to overcome Judeo-Christian morality and attack innocent women and children.[18]

Identification

The boy

There are several individuals who have been claimed to be the boy in the photo, but his identity remains unclear.[7][10][17] All of the proposed claimants' stories are inconsistent with the known facts about the photograph.[6] The boy was probably younger than ten, because he was not wearing a Star of David armband.[17] Dr. Lucjan Dobroszycki, a historian employed by the Yivo Institute for Jewish Research who has studied the photograph, stated that "This photograph of the most dramatic event of the Holocaust requires a greater level of responsibility from historians than almost any other... [i]t is too holy to let people do with it what they want."[19][20]

- Artur Dąb Siemiątek, born in Łowicz in 1935, was first proposed as the subject of the photo in 1950. Siemiątek was from a well-off family and his father was a member of the Judenrat in the Łowicz Ghetto, liquidated to Warsaw in 1941. Jadwiga Piesecka, a cousin of Siemiątek and resident of Warsaw, and her husband fled to the Soviet Union in September 1939. They survived the Holocaust and signed affidavits that Siemiątek was the boy in the photo in the 1970s.[10][14]

- In 1999, a 95-year-old man named Avrahim Zelinwarger told the Ghetto Fighters House in Israel that the boy in the photo was his son, Levi Zeilinwarger, born in 1932. Avrahim escaped to the Soviet Union in 1940, but his wife Chana (who would be the woman in the photograph), son, and daughter are all believed to have been killed during the Holocaust. Richard Raskin personally doubted the Zelinwarger claim because of the lack of resemblance between Levi and the boy in the photograph.[10][14]

- In 1978, Israel Rondel told the Jewish Chronicle that he was the boy in the photograph, but because he said that the photograph was taken in 1941, and other details do not match, his claim has been dismissed.[10][21][6]

- Tsvi Chaim Nussbaum (de, fr) (1936–2012)[22] was born in Tel Aviv but his family returned to Poland before the war. He lived in hiding on the "Aryan" side of Warsaw. Since he and his family had valid Palestinian visas, they fell into the Hotel Polski trap in which the Germans promised safe passage out of occupied Europe. Liberated by American troops at Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in 1945, Nussbaum stated in 1982 that he had been arrested in front of the Hotel Polski on 13 July 1943 and forced to raise his arms as depicted. Although some Jewish organizations uncritically accepted this claim at the time it was made, it is not possible that Nussbaum was the boy in the photo.[19][20][14] Nussbaum himself never claimed to be certain about the identification, saying "I think it’s me, but I can’t honestly swear to it. A million and a half Jewish children were told to raise their hands".[10][19] Dobroszycki pointed out the discrepancies between Nussbaum's claim and what is known about the photograph. All images in the Stroop Report are believed to have been taken inside the Warsaw Ghetto, while the Hotel Polski is not in the ghetto. The Hotel Polski roundups occurred in a courtyard, while the photograph depicts a street. Most of the Jews in the photograph are wearing heavy clothing, which suggests that the photograph was not taken in July; they are wearing armbands that they would not have worn while in hiding on the "Aryan" side of the city. The Germans are wearing combat uniforms which they would not have needed at the Hotel Polski roundups. Furthermore, Nussbaum was arrested more than a month after the Stroop Report was delivered to Himmler.[19][20][23] A comparison with Nussbaum's 1945 photograph by forensic anthropologist K. R. Burns of the University of Georgia revealed that Nussbaum had detached earlobes, unlike the boy in the photograph.[10]

Other individuals

The woman emerging from the building directly behind the boy was Gołda Stawarowska, according to Stawarowska's granddaughter Golda Shulkes. The boy with the white bag over his shoulder was identified as Ahron Leizer (Leo) Kartuziński (or Kartuzinsky)[24][25] from Gdańsk by his sister, Hana Ichengrin. The same person was also identified as Harry-Haim Nieschawer.[24] Polish-American Holocaust survivor Esther Grosband-Lamet said that the small girl on the extreme left foreground was her niece Channa (Hanka) Lamet[24][25] (or Hannah Lemet) (1937–1943) who was murdered at Majdanek. The woman wearing the scarf would then be Hanka's mother Matylda Goldfinger-Lamet[25] or Mathylda Lamet Goldfinger,[24] married to Mosze Lamet; the family was from Warsaw.[10][14][7]

The only identification that is certain is that of Rottenführer Josef Blösche, the SS man aiming the MP 28 submachine gun at the boy.[1][10][14] Blösche was born in the Sudetenland in 1912 and served in the Einsatzgruppen,[10] and he was a policeman employed at the Warsaw Ghetto during the uprising. Marek Edelman testified that Blösche murdered Jews as part of his "daily routine" and he was known to have committed violence against children and pregnant women.[1][14] Due to his performance during the suppression of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising, Blösche was awarded the War Merit Cross 2nd Class with Swords.[10] Blösche appears in several of the photographs in the Stroop Report. During his trial in East Germany, the photographs were used as circumstantial evidence for the prosecution. He was convicted of the murder of at least 2,000 people and executed in 1969.[14] Of the photograph, Blösche stated:

The picture shows me, as a member of the Gestapo office in the Warsaw Ghetto, together with a group of SS members, driving a large number of Jewish citizens out from a house. The group of Jewish citizens is comprised predominantly of children, women and old people, driven out of a house through a gateway, with their arms raised. The Jewish citizens were then led to the so-called Umschlagplatz, from which they were transported to the extermination camp Treblinka.[10]

During the trial, the Judge asked Blösche about the events depicted in the infamous photograph:

Judge: "You were with a submachine gun...against a small boy that you extracted from a building with his hands raised. How did those inhabitants react in those moments?"

Blösche: "They were in tremendous dread."

Judge: "This reflects well in that little boy. What did you think?"

Blösche: "We witnessed scenes like these daily. We could not even think."[26]

Legacy

The New York Times published the picture on 26 December 1945 along with others from the Stroop Report, which had been entered into evidence at the Nuremberg Trial. On 27 December it reprinted the photograph, stating:

The luckier of the ghetto's inhabitants died in battle, taking some Germans with them. But not all were lucky. There was a little boy, perhaps 10 years old. A woman, glancing back over her shoulder at the supermen with their readied rifles, may have been this boy’s mother. There was a little girl with a pale, sweet face. There was a bareheaded old man. They came out into the streets, the children with their little hands raised in imitation of their elders, for the supermen didn't mind killing children.[6]

The photograph was not well known until the 1970s,[16] perhaps because most countries preferred to celebrate resistance to Nazism rather than the anonymous victims. In 1969, it appeared on the cover of the English edition of the Gerhard Schoenberner work The Yellow Star.[13] In 2016, Time Magazine listed it as one of the 100 most influential photographs of all time, stating that it had an "evidentiary impact" exceeding that of the many other "searing images" produced during the Holocaust; the child "has come to represent the face of the 6 million defenseless Jews killed by the Nazis".[2] Several books have been written about the photograph, including A Child at Gunpoint: A Case Study in the Life of a Photo by Richard Raskin, The Boy: A Holocaust Story by Dan Porat, and L'Enfant juif de Varsovie. Histoire d'une photographie (transl. The Jewish child of Warsaw: History of a photograph) by Frédéric Rousseau.[1][16] The photograph is perceived differently by the SS man who took it and other observers; in Raskin's words, "one set of men saw in that photograph heroic soldiers combating humanity's dregs while the vast majority of mankind sees here the gross inhumanity of man".[1][16] According to Eva Fogelman, the photograph has promoted the myth that Jews went passively "like sheep to the slaughter".[27]

The image has been used in some controversial artwork juxtaposing the Warsaw Ghetto uprising with the Second Intifada in Gaza, which some argue is tantamount to Holocaust trivialization. In The Legacy of Abused Children: from Poland to Palestine by British-Israeli artist Alan Schechner, a camera zooms in on the boy in the photo, who is holding a different photograph of a child in Gaza being carried by IDF soldiers. Schechner stated that he did not intend to compare the Holocaust with the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, but merely illustrate the suffering of children because of the cycle of violence in which trauma causes victims to become abusers. A different approach was used by Norman Finkelstein in a photo-essay titled "Deutschland über alles", also juxtaposing the Warsaw photograph with images of Palestinian suffering. The subtitle read in all caps: "the grandchildren of Holocaust survivors are doing to the Palestinians exactly what was done to them by Nazi Germany".[4]

The Holocaust survivor and artist Samuel Bak has created a series of more than a hundred paintings inspired by the photograph, as well as by his own experiences and the memory of a lost childhood friend. In these works, the boy's extended arms are often depicted with a crucifixion theme or with the boy seen as a part of an imagined monument.[28][29]

Both NARA and IPN describe the image as in the public domain. However, in the 1990s Corbis Corporation acquired the photograph from Bettmann Archive and licensed three versions of it, charging commercial rates for its usage.[15] As of 2018[update], Getty Images, which acquired Corbis license rights in 2016,[30] continues to offer it for sale, providing a copy of it with a copyright claim watermark as a sample.[31]

Notes

- ^

- Haaretz: "One of the most compelling and enduring images of the Holocaust"[1]

- Time Magazine: "The Holocaust produced scores of searing images. But none had the evidentiary impact of the boy’s surrender."[2]

- Tablet Magazine: "The boy in question can be seen in one of the most famous images of the Holocaust"[3]

- Michael Rothberg: "the frequently reproduced photograph of a boy in the Warsaw Ghetto with his hands up—perhaps the most famous image from the Holocaust"[4]

- Jarosław Marek Rymkiewicz: "The photograph everyone knows: a boy in a peaked cap and knee-length socks, his hands raised"[5]

- Daniel H. Magilow and Lisa Silverman: "the image soon came to symbolize the entirety of the Holocaust".[6]

- ^

- Time Magazine: "The child, whose identity has never been confirmed, has come to represent the face of the 6 million defenseless Jews killed by the Nazis."[2]

- Haaretz: "A Picture Worth Six Million Names"[1]

- Hidabroot: "His anonymity symbolizes the one and a half million children who perished in the Holocaust and were reduced to ashes."[7]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g Maltz, Judy (3 March 2011). "Holocaust Studies / A picture worth six million names". Haaretz. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- ^ a b c "How A Little Boy Became the Face of The Holocaust". Time Magazine. No. 100 Photographs | The Most Influential Images of All Time. 17 November 2016. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- ^ a b c d Kirsch, Adam (23 November 2010). "Caught on Film". Tablet Magazine. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- ^ a b Rothberg, Michael (Fall 2011). "From Gaza to Warsaw: Mapping Multidimensional Memory". Criticism. 53 (4). Wayne State University Press: 532, 536–537. doi:10.1353/crt.2011.0032. JSTOR 23133895. S2CID 144587788.

- ^ a b Radstone, Susannah (January 2001). "Social Bonds and Psychical Order: Testimonies". Cultural Values. 5 (1): 64–65. doi:10.1080/14797580109367221. ISSN 1479-7585. S2CID 144711178.

- ^ a b c d Magilow, Daniel H.; Silverman, Lisa (2019). "The Boy in the Warsaw Ghetto (photograph, 1943): What Do Iconic Photographs Tell Us About the Holocaust?". Holocaust Representations in History: An Introduction. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-1-350-09182-5.

- ^ a b c Stein, Shira (24 August 2014). "Who is that Boy in the Famous Warsaw Ghetto Picture?". Hidabroot. Archived from the original on 24 September 2018. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- ^ a b Freilich, Miri; Dean, Martin (2012). "Warsaw". In Megargee, Geoffrey P.; Dean, Martin; Hecker, Mel (eds.). Ghettos in German-Occupied Eastern Europe. Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945. Vol. 2. Translated by Fishman, Samuel. Bloomington: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. pp. 456–459. ISBN 978-0-253-00202-0.

- ^ a b Tomasz Stempowski (17 March 2013). "Zdjęcia z powstania w getcie" [Photos of the ghetto uprising] (in Polish). Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Raskin, Richard (2007). "The Boy in the Photo?". Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- ^ a b c "Stroop Report (full high resolution copy)". Tiergartenstrasse 4 Association. Archived from the original on 30 March 2015. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- ^ a b c d "Stroop's Report in the new version". Jewish Historical Institute. Archived from the original on 24 September 2018. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- ^ a b c Jeannelle, Jean-Louis.""L'Enfant juif de Varsovie. Histoire d'une photographie", de Frédéric Rousseau" [The Jewish child of Warsaw. The story of a photograph by Frédéric Rousseau]. Le Monde (in French). 8 January 2009. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Nowik, Mariusz (19 May 2018). "Only the oppressor has a name. The story of the boy from the picture". TVN24. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- ^ a b Struk, Janina (2004). Photographing the Holocaust: Interpretations of the Evidence. I.B. Tauris. pp. 208–209. ISBN 978-1-86064-546-4.

- ^ a b c d e Sumpf, Alexandre. "L'enfant juif de Varsovie" [The Jewish child of Warsaw] (in French). 2 October 2013. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- ^ a b c "Boy An Icon For Childhoods Lost In Holocaust". NPR. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- ^ Kowalski, Waldemar. "To zdjęcie z getta mówi więcej niż tysiąc słów. Wypędzani Żydzi, eskorta Niemców i przerażony wzrok małego chłopca..." [This picture from the ghetto says more than a thousand words. Expelled Jews, an escort of Germans, and the terrified eyes of a small boy...]. NaTemat.pl (in Polish). 19 April 2016. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- ^ a b c d Margolick, David (28 May 1982). "Rockland Physician Thinks he is the Boy in Holocaust Photo Taken in Warsaw". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- ^ a b c Berger, Joseph (12 October 2012). "The Ghetto, the Nazis and One Small Boy". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- ^ Harris, Clay (17 September 1978). "Warsaw Ghetto Boy-Symbol of The Holocaust". The Washington Post. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- ^ "Dr. Tsvi Chaim Nussbaum". The Journal News. Archived from the original on 24 September 2018. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- ^ Kleikamp, Antonia (29 April 2018). "Warschau 1943: Wer ist der Junge auf dem berüchtigten Getto-Foto?" [Warsaw 1943: Who is the boy in the infamous ghetto photograph?]. Die Welt (in German). Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- ^ a b c d "German soldiers pointing guns at women and children during the liquidation of the ghetto. The original German caption (Stroop collection) reads: "Pulled from the bunkers by force" Warsaw, Poland, April 19 – May 16, 1943". Yad Vashem. Archived from the original on 3 February 2022. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- ^ a b c "Jews captured by SS and SD troops during the suppression of the Warsaw ghetto uprising are forced to leave their shelter and march to the Umschlagplatz for deportation". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 11 October 2018. (Photograph Number: 26543)

- ^ Porat, Dan (2013). The Boy: A Holocaust Story (in Hebrew). Dvir.

- ^ Middleton-Kaplan, Richard (2014). "The Myth of Jewish Passivity". In Henry, Patrick (ed.). Jewish Resistance Against the Nazis. Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press. p. 8. ISBN 9780813225890.

- ^ "Holocaust Survivor/Artist Asks Tough Questions". Wabash College. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- ^ Fewell, Danna Nolan; Phillips, Gary Allen (2009). Icon of loss : the haunting child of Samuel Bak (PDF). Bak, Samuel. Boston: Pucker Art Publications. ISBN 978-1-879985-21-6. OCLC 318057887.

- ^ Laurent, Olivier. "The Decade-Long Image Licensing War Is Suddenly Over". TIME. Retrieved 8 November 2018.

- ^ "Nazis Arresting Jews in Warsaw Ghetto". Getty Images. 7 October 2016. Retrieved 1 November 2018.

Further reading

- Kicińska, Magdalena; Dziedzic, Marcin (2018). Teraz '43 [Now '43] (in Polish). ISBN 9788380322448. Wydawnictwo Wielka Litera

- Porat, Dan (2011). The Boy: A Holocaust Story. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0-8090-3072-9.

- Raskin, Richard (2004). A Child at Gunpoint: A Case Study in the Life of a Photo. Aarhus University Press. ISBN 9788779340992.

- Rousseau, Frédéric (2014). L'Enfant juif de Varsovie. Histoire d'une photographie [The Jewish Child of Warsaw: History of a Photograph] (in French). Le Seuil. ISBN 9782021212334.

External links

Media related to Photograph of the Warsaw Ghetto Boy at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Photograph of the Warsaw Ghetto Boy at Wikimedia Commons